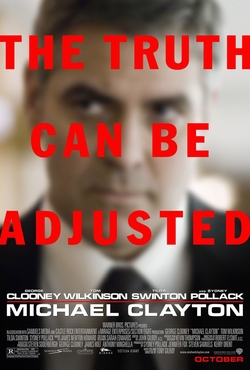

When we first meet Michael Clayton, the title character of Tony Gilroy’s sinister and cynical 2007 thriller, he’s standing in the kitchen of a grossly entitled man who has committed a hit-and-run. The perpetrator snivels that Michael’s law firm, Kenner, Bach & Ledeen, has promised a “miracle worker.” Michael, played by a weary George Clooney, stiffens. “I’m not a miracle worker,” he tells the man, “I’m a janitor.” Michael’s days of practicing law are behind him.

Once upon a time he was a prosecutor for the Queens County district attorney’s office. Now he’s a fixer, cleaning up extralegal messes for his firm. “You have a niche,” explains his boss and friend, Marty Bach (Sydney Pollack). These days, however, Michael doesn’t much care for his niche.

Michael Clayton plays like a movie out of time, a bold ‘70s-style thriller transplanted to the risk-averse film landscape of the 21st century. It’s a legal thriller that lawyers seem to love, even though the main lawyers it portrays are either corrupt or insane.

This is a shadowy, taciturn world in which a corporate executive can order up a murder like she was calling in dinner and the bagman is left holding the bag. In this world the darkness is taken for granted, barely worth even noting — until one of the principals loses his mind and another gradually grows a conscience.

The crazy one is Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkerson), the firm’s killer litigator tasked with defending an agrichemical behemoth, UNorth (think Monsanto), in a class-action suit. But is he really crazy?

It seems UNorth has been contaminating well water. Bad timing: The company is also on the verge of a massive corporate merger.

Arthur, apparently a manic depressive who occasionally stops taking his meds, has grown obsessed with one of the plaintiffs, a farmer’s daughter, who he sees as a paragon of purity. He strips naked during a deposition and makes it clear he will spill the tea on UNorth’s nefarious business practices. He has switched sides.

This makes him a liability, one that UNorth executive Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton, earning her supporting actress Oscar as an icy corporate sociopath) has eliminated in one of the most chilling murder sequences in movie history.

Arthur, mad or not, pays the price for putting matters of right and wrong ahead of legal and corporate expediency. In the movie’s world only the unbalanced or the desperate can see clearly — and Michael is growing increasingly desperate.

Initially this is merely a matter of finances: The upscale bar he opened with his addict brother has gone belly-up, and he’s deep in debt to people you don’t want to owe money. His employer takes care of that, in a manner that feels a little like hush money.

Michael deeply admired Arthur. He starts snooping around, which puts him next on the hit list. By then, his crisis is more existential than economic. He no longer likes who he is or what he does. And he sees a way he can do something about it, even if it brings his firm down around him.

Is Michael Clayton a lawyer movie?

It’s a fair question, given that the main character isn’t really a lawyer. He operates in the dark corners of the legal profession, trying not to get too dirty, until he reaches a point where he can no longer look at himself in the mirror. He comes down with a bad case of scruples, which, here, can be fatal. He trades off his profession’s reputation after Karen tries to have him killed. “I’m not the guy you kill. I’m the guy you buy. Are you so fucking blind that you don’t even see what I am?”

And yet, by movie’s end, against all odds, he can’t be bought. But Michael Clayton isn’t the kind of movie to supply an unequivocal happy ending. Having settled accounts, Michael climbs into the back of a New York City cab, hands the driver some money and tells him to drive — anywhere. The credits roll over Clooney’s pensive face.

Michael has done the right thing. There’s no telling what comes next.