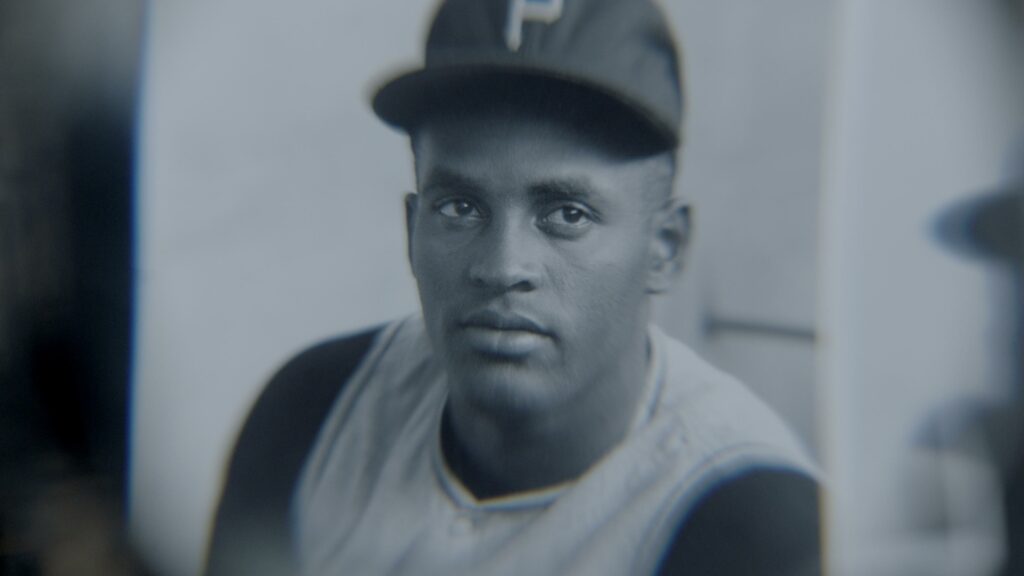

A portrait of MLB trailblazer Roberto Clemente

When Roberto Clemente made it to “the show” in 1955, sportswriters and baseball card manufacturers took to calling him “Bob” — not out of informality but because they felt the need to deracinate his name and his appeal. Baseball was still decades away from the days when every big league roster became stocked with Latin players, and the Puerto Rican phenom posed some sort of threat to the established (white American) order. Those same writers would quote Clemente by denoting his thick accent — for example, “heet” instead of “hit.” If Clemente sometimes seemed to have a chip on his shoulder, it’s not difficult to see why.

The man bluntly and accurately nicknamed The Great One is now the subject of an affectionate and thorough documentary, simply called Clemente, that premiered at the SXSW Film Festival in March. The film is a celebration of a player who has long since entered the pantheon of baseball saints, a pure talent who played with abandon and turned himself into one of the all-time greats — and yet, somehow, still remains underrated. He was too smart and dignified to ignore the free-floating racism around him, especially in the years before he became a superstar in the ‘60s, a decade in which Willie Mays and Hank Aaron were his only true rivals. He wasn’t warm and cuddly and readily accessible to the press. But as the film shows, he would give the person off the street the jersey on his back.

“Her was our Jackie Robinson,” says Clemente’s Puerto Rican countryman and fellow Hall of Famer Orlando Cepeda in the film, and he could be speaking for all Latin players. Clemente’s former teammate, the Panamanian catcher Manny Sanguillén, recalls how Clemente took him under his wing, helped him learn English and showed him the ropes of life in the majors. Clemente suffered the slings of arrows from African American players who questioned his Blackness and white players who saw him as some unidentifiable Other. As his career progressed, however, he just became too dominant on the field, and too genuinely human off of it, to garner anything but admiration.

Produced by a team including Texans Richard Linklater (who appears in the film as a Clemente fan) and Mike Blizzard, as well as NBA superstar LeBron James, Clemente, directed by Pennsylvania native David Altrogge, unfurls as a tribute. But how else might one approach the subject? Celebrity fans, including Michael Keaton, Rita Moreno and Tom Morello, line up to give their testimonials. Then there are the more everyday believers. Like the woman who, as a child, befriended Clemente after a game and had her father give him a ride to the airport after the team bus left, starting a lifelong friendship. Or the kid who, outside his family’s Pittsburgh home, saw Clemente driving down the street, flagged him down, tossed the ball around and asked the star to stay for dinner. Clemente, of course, said yes. The bond that developed between Clemente and blue-collar Pittsburgh, whose Pirates were the only team for which The Great One played, was thick. Hard work recognizes hard work.

Clemente was also a humanitarian. He died in a 1972 plane crash en route to deliver emergency aid supplies to Nicaragua in the wake of a massive earthquake (and to keep those supplies from being heisted by corrupt government officials). The plane and the crew were woefully inadequate to the task. Clemente, already considered a saint by many, was now also a martyr. “I like people that suffer,” he says in footage from an interview given late in his life. He liked people who weren’t handed anything. He could relate.

Then there’s the pleasure of watching Clemente in action: roping the ball all over the park (he won four batting titles), running the bases like a gazelle and reaching balls in the outfield that few others in the game could have reached (he won 12 consecutive Gold Glove Awards, from 1961 to 1972, the year he died). And he did it all with understated bravura. “Did he know that he looked that cool?” asks Pennsylvania native Keaton rhetorically, still marveling at his boyhood memories. If he did, he never talked about it. He played and he led and he gave until his last breath. Clemente is a vivid reminder of what greatness looks like and how Clemente became The Great One.