Texas’ new business court and Fifteenth Court of Appeals are now open for business. But how do you get your case into — or out of — those courts? And how do you move your case between divisions within the business court?

As a threshold matter, it is important to understand the structure of the business court, particularly which divisions are open and which are not.

The business court is a single, specialized trial court divided into 11 geographical divisions. Five divisions, which encompass the five largest cities (Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio and Austin) and their surrounding counties, are operational already. The remaining six divisions will begin operating in 2026 only if they are reauthorized by the Texas Legislature during the 2025 legislative session and funded through additional legislative appropriations. Each of the five operational divisions has two judges, while each of the six forthcoming divisions will have one judge.

A map of the divisions and a list of the counties served by each division can be found on the business court’s website here and here, respectively.

For a case to be allowed in business court, two requirements must be satisfied: jurisdiction and venue. First, the business court must have jurisdiction over the case. The business court’s jurisdiction is concurrent with the district courts’ jurisdiction for certain types of civil cases, as provided by section 25A.004 of the Texas Government Code. Second, a county in an operating division of the business court must be the proper venue for the case. Venue is established as provided by traditional law or, if a written contract specifies a county as the venue for the case, as provided by the contract.

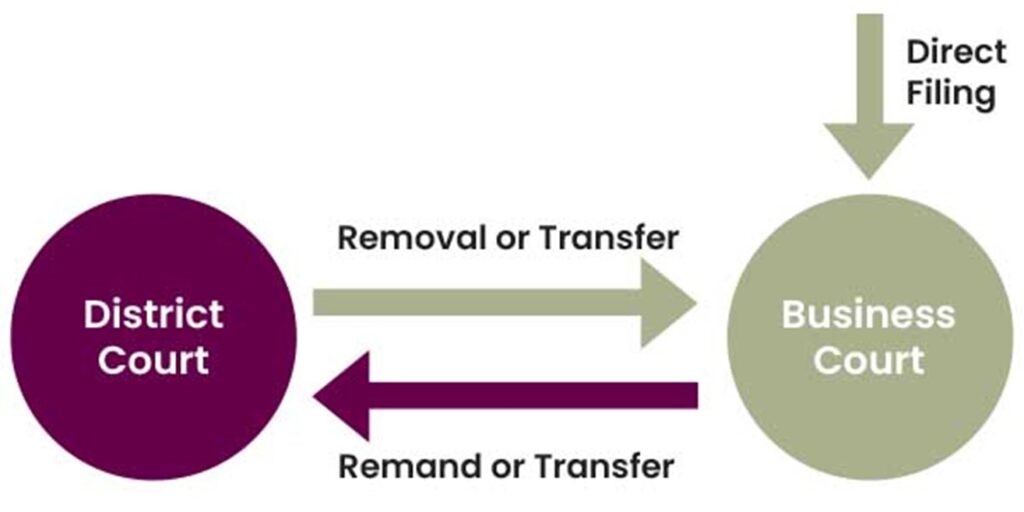

The figure below depicts the basic procedural methods for getting cases into and out of the business court — direct filing, removal, transfer and remand.

When the jurisdictional and venue requirements are satisfied, a plaintiff may file a case directly in the business court. When filing, there is an option to select the proper business court division. If the division has more than one judge, the court clerk will randomly assign the case to a judge within that division.

Presumably, some plaintiffs will file their case in district court even though they could have filed in business court. In that circumstance, the defendant may remove the case to business court, so long as the case was filed on or after Sept. 1 of this year.

The procedure for removing from district court to business court is similar to the procedure for removing from state court to federal court. The defendant files a notice of removal (in both the district court and business court), which triggers immediate removal of the case to business court.

There are several differences from federal-court removal, though. One notable difference is that removal to business court may occur at any time during the case if all parties agree to removal (and the jurisdictional and venue requirements for business court are satisfied). Absent agreement, the deadline for removal is 30 days after the defendant discovered, or reasonably should have discovered, facts establishing the business court’s jurisdiction — with extended time if an application for temporary injunction is pending upon such discovery.

Another notable difference is that the district court on its own initiative may ask the presiding judge for the administrative judicial region to transfer a case to the business court (again, so long as the jurisdictional and venue requirements for business court are satisfied). When this occurs, the district court must provide the parties notice and an opportunity to be heard. If the presiding judge denies transfer, a party may challenge such denial via a petition for writ of mandamus to the court of appeals.

After filing, removal, or transfer to the business court, a party may file a motion challenging the business court’s jurisdiction. The deadline to do so is generally 30 days. In addition, the business court may consider its jurisdiction on its own initiative, so long as it gives the parties notice and an opportunity to be heard. If the business court determines that it lacks jurisdiction, then it must do one of the following:

- If the case was removed or transferred from district court, then remand back to that district court; or

- If the case was originally filed in business court, then at the option of the party who filed the case, either

- transfer the case to a proper district court, or

- dismiss the case without prejudice.

Not only may a case be moved between the district court and business court, but also a case may be moved between divisions of the business court. If the assigned division does not include a county of proper venue for the case, then a party may file a motion challenging venue. The motion should comply with the preexisting rules for challenging venue in traditional cases. If the business court determines that venue is indeed improper, then it must do one of the following:

- If a proper business court division is operational, then transfer the case to that division; or

- If there is not a proper business court division that is operational yet, then at the option of the party who filed the case, transfer the case to a proper district court.

All appeals from the business court — as well as certain other appeals from district courts — fall under the exclusive jurisdiction of the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals.

If an appellant files an appeal in the wrong court of appeals (either in the Fifteenth Court of Appeals improperly or in a different court of appeals when the Fifteenth Court has exclusive jurisdiction), then the appellee may file a motion to transfer the appeal. The motion should be filed within 30 days but must be filed by the date the appellee’s brief is filed. In addition, the court of appeals in which the appeal was filed may seek to transfer the appeal on its own initiative.

Transfers between courts of appeal are unique in that both the transferor and transferee courts of appeals must determine whether transfer is appropriate. Before effectuating a transfer, the transferor court must give the transferee court notice of the transferor court’s intent to grant a motion to transfer or transfer on its own initiative. Then the transferee court must file a letter in the transferor court explaining whether the transferee court agrees with the transfer. If the courts of appeals agree, then the transfer may occur.

If the courts of appeals disagree, then the court forwards any motion to transfer, related briefing, and courts of appeals’ determination letters to the Texas Supreme Court — without the parties filing anything in that court themselves. Then the Texas Supreme Court decides whether the appeal should be transferred.

The procedures discussed above, plus details not covered by this article, are set forth in rules and statutes. The business court procedures are in rules 352 through 360 of the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure and chapter 25A of the Texas Government Code. The business court’s website contains links to these authorities as well as other helpful resources, including a copy of a memorandum to court clerks describing filing, removal, transfer, and remand procedures. The procedures for transferring to and from the Fifteenth Court of Appeals are in rule 27a of the Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure.

Armed with this knowledge, hopefully getting your case into or out of the new courts will go smoothly.

Natasha Belle Breaux is a partner in the Houston office of Haynes Boone. She practices appellate litigation and is a member of Haynes Boone’s Texas Business Courts Task Force, which is staying up to date on the new courts.