Prior to this most recent legislative session, the last time lawmakers agreed to fund more civil courts in Harris County, the Astros were still playing in the Astrodome, the region was recovering from Hurricane Alicia and the second-tallest skyscraper in downtown Houston, now called the Wells Fargo Plaza, had just opened.

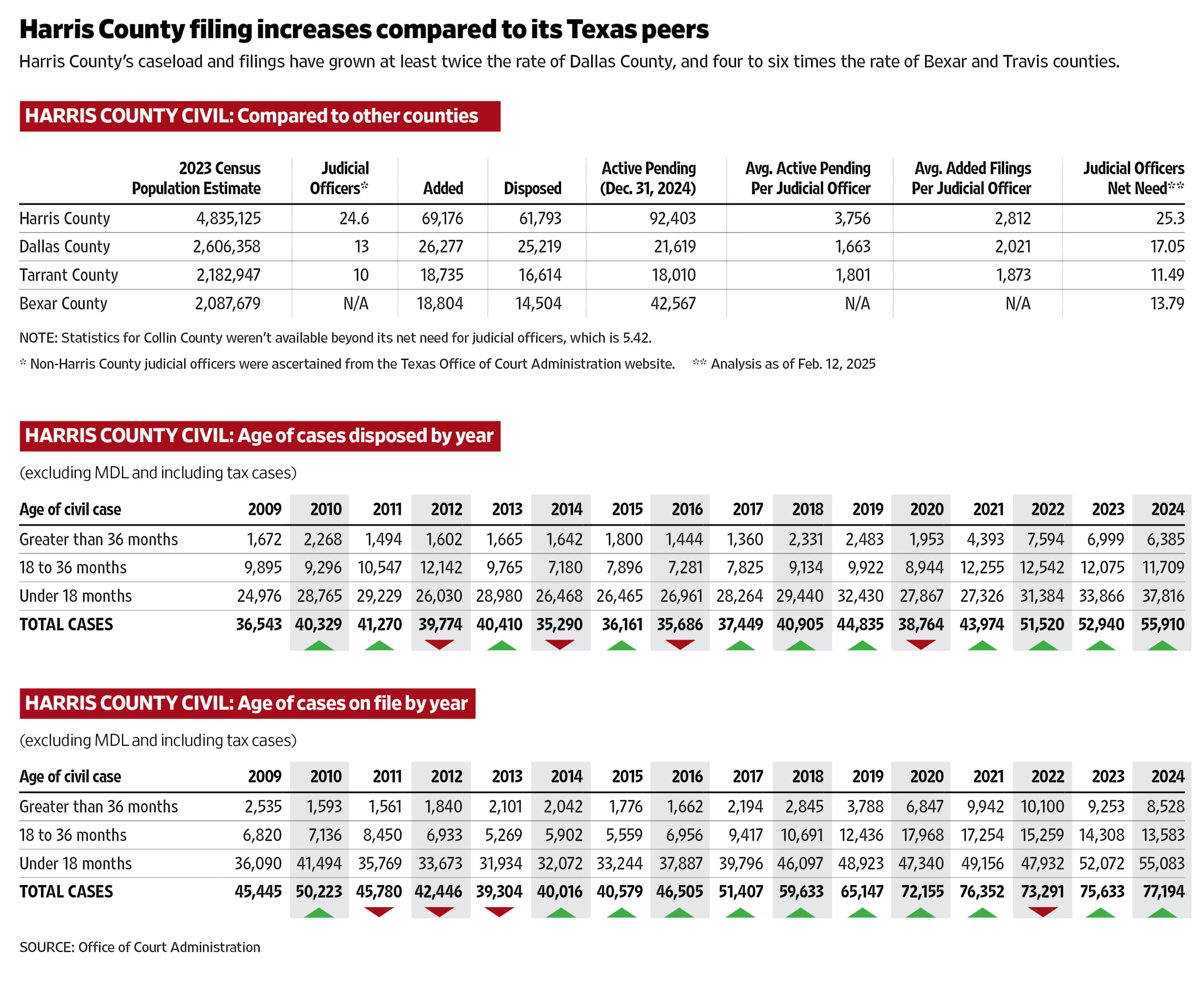

Back then, in 1983, the population of Harris County was about 2.7 million, compared to an estimated 5 million residents today. As the population increased so, too, did the number of civil lawsuits filed. The judges who presided over those courtrooms, while stretched thin, were diligent in their efforts to keep pace, data show, juggling caseloads twice the size of their colleagues in Dallas and four to six times larger than judges in Bexar and Travis counties.

Contending with population growth wasn’t the only issue that made the timely disposition of cases difficult.

Hurricane Harvey, which hit in 2017, nearly destroyed the Harris County Criminal Courthouse. Floodwaters infiltrated the lower levels, and the unrelenting rain penetrated the building’s roof and trickled down for days throughout its 21 stories. Those criminal court judges would, for nearly three years, share courtroom and chamber space with the neighboring civil district court judges, exacerbating the backlog.

And just when repairs were completed next door and the civil judges were about to get their courtrooms back fulltime, the pandemic brought everything to a halt in March 2020.

Twenty legislative sessions came and went without relief in the form of more civil district courts to handle the growing load. Harris County District Judge Latosha Lewis Payne, who also serves as the county’s administrative judge, said lawyers came to expect the sluggish pace of justice in the civil courts. She practiced in Harris County for nearly 20 years before taking the bench in 2019.

“There are standards out there that help us determine what’s a backlog … and the general standard is 18 months. But having been a litigator here, I knew that was an impossible goal,” she said. “I typically would double that amount of time, and that’s what I would counsel my clients. We’ll be lucky if we get to trial in three years.”

“And so, I think as litigators, we became really accustomed to that,” she said. “Once you get accustomed to it — this is the world we live in — there was very little objection.”

Once she took the bench, she said it became clear to her that “we either need to change the standard of what the expectation is, or we right-size the courts so we can meet, in most cases, that 18-month standard.”

Next year, for the first time in 42 years, three new civil district courts will go live in Harris County, and two more will follow in 2027, bringing the total number of civil courts there 29, helping to improve docket efficiency and enhance access to justice in the state’s most populous county.

Creating a district court in Texas is a two-step process. The commissioners, who are responsible for funding everything related to court operations except for the salary of the judge, must agree to the proposal. And then it’s on to Austin, where lawmakers are tasked with creating the new district court. The state pays the judge’s salary.

Getting those new courts — at a time when the political relationship between Austin and Harris County is less than collaborative — was a task that required building a broad, bipartisan coalition, according to both Judge Payne and Judge Beau Miller, who serves as the chair of the district courts’ legislative committee.

Judge Miller, a Democrat, said his efforts were aided in part by relationships his father, Rick Miller, had built during eight years serving as a Republican representative from Fort Bend County in the state house.

“As you know, a lot of what gets done is through contacts, through relationships,” he said, noting his relationships with members of the Harris County Commissioners Court and prominent lawyers on both sides of the political spectrum were also valuable in accomplishing the goal.

“When we went to Commissioners Court, we had a lot of support from the bar, we had support from the different affinity bar groups, we had support from each of the class presidents of the local law schools, and then we had to make our pitch ourselves. I think the dynamic part of that pitch to the county commissioners was the great support we had across the bar.”

Having broad support for the proposal, he said, helped drive home the message “that this is not a one-party issue. This is a Texas justice need for all people.”

The data showed Harris County needed 25 new civil district courts to keep up with the rising tide of filings and chip away at the backlog, but making such a large request to the Harris County Commissioners Court wasn’t the strategic move the judges wanted to make. Judge Payne said the judges involved in crafting the proposal wanted to ask for a number of courts that was “persuasive and not overwhelming.”

They instead settled on asking for nine new courts.

“We understood that’s a huge ask,” Judge Miller said. “Courts aren’t cheap.”

After the commissioners agreed to financially support the creation of five new courts, it was on to Austin.

“We needed Republicans to join us in a big way,” Judge Miller said of getting support in the Capitol. “The data showed the need. It was undeniable.”

Another member of the bipartisan coalition was Business Court Judge Grant Dorfman, a Republican. As a former Harris County district court judge, he was able to speak to lawmakers about the need in Houston and why more general jurisdiction civil courts are still needed one session after the creation of the Texas Business Court.

“As a two-time veteran of the Harris County Civil District Court, I know the constraints and burden those judges labor under with the number of cases on their docket,” he said. “And as presiding judge of the [Business] Court, I could be a voice that legislators could hear from directly… that we’re grateful for our court, but it serves a very narrow slice of the total civil district court docket.”

The new courts in Harris County were created via the passage of HB 16, authored by Rep. Jeff Leach (R-Allen), who is also a partner at Gray Reed & McGraw and did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“He was hugely supportive,” Judge Miller said of Leach’s engagement on the issue. “He was never a ‘no’ or ‘I don’t think so.’”

Among other things, the legislation also created new judicial districts in a handful of additional counties: Brazoria, Colorado, Comal, Ellis, Fort Bend, Lavaca, Rockwall and Williamson.

Judge Payne said the impact of the five new courts in Harris County should be felt immediately.

“I know that the colleagues I have here on the bench now are former trial lawyers who want to be in the courtroom and who will push their cases to trial,” she said. “That combination of having trial lawyers on the bench pushing trials and having a more equitable distribution of the cases will definitely bring down the wait times for litigants.”