Ancient leaders throughout history have shown us what it takes to overcome obstacles. Their leadership lessons are as fresh and relevant today as they were thousands of years ago, perhaps even more-so as we face similar challenges brought on by war, pandemics (plagues), weather or social and political upheaval. Especially instructive for a general counsel today are the enduring leadership lessons of Alexander III (the Great) of Macedon, Marcus Aurelius of Rome, Socrates of Greece and Confucius of China. Each offers valuable lessons for our boardrooms, war rooms or courtrooms. I certainly have found them helpful in my 40-plus years of practicing law. The past informs the future and there is literally nothing new under the sun.

Alexander the Great

Recently, I had the good fortune to travel in the footsteps of Alexander III, born in Pella in June 356 BC, the son of Macedonian King Phillip II and mother Olympias. Much of what I learned in my research on this trip is captured in this article. When Alexander was 13 years old, his father hired philosopher Aristotle, who served as the boy’s tutor and mentor until Alexander was 16. Although Alexander certainly was influenced by his tutor’s teachings, he developed his own revolutionary leadership ideas. I will discuss several of these valuable lessons below.

Ancient Pella Greece

Be Magnanimous Toward Your Enemies

Pictured right: Gold Larnax of Philip II, Vergina, Greece

Aristotle counseled: “act toward the Greeks as a leader and toward the barbarians as a conqueror … take care of the former as friends and relatives and … behave [toward] the latter as animals and plants.” (Plutarch, De Alexandri magni fortuna aut virtute, A’, 6.) Alexander, however, had a contrarian view; he was not interested in one’s descent and chose not to distinguish between “Greeks and barbarians” but based on virtue: “for this reason he welcomed and benefitted honorable people.” (Strabo, I.4, 9.)

This is the first leadership lesson: be magnanimous to your enemies and those you conquer or defeat in life. This acceptance of diversity, peaceful cultural coexistence, allowed him to integrate those he defeated into his growing empire, ultimately the largest the world had known. Alexander also was adept at building alliances among the nations he conquered, earning their trust and respect, consolidating his gains and expanding his empire.

Lead from the Front or by Example

As a military leader, Alexander showed his skills in battle when, at 18, he rode to victory with his father, Phillip, in the Macedonian Companion Cavalry at the Battle of Chaeronea. When Phillip was assassinated in 336 BC, Alexander ascended to the throne of Macedon at just 20. After consolidating his power, he prepared to complete his father’s plans to invade Persia, leading his army by example, from the front, the second leadership lesson. In other words, he walked the talk. The supreme motivator and ultimate leader, he deliberately placed himself at personal risk and was seriously wounded in battle at least eight times, five of them nearly fatal, including the lung wound described below:

At one rebel town in India, Alexander spearheaded an assault. … He scaled a siege ladder his men were reluctant to climb and, as if shaming them, stood atop the wall exposed to hostile fire. A brigade of infantry sprang up after him, but the ladder broke under their weight. Unfazed, Alexander leaped down off the walls and into the town, accompanied by only three comrades. In the ensuing melee, an Indian archer sent a three-foot-long arrow right through Alexander’s armor and into his lung. His panic-stricken troops burst open the gates to the town and dragged his body out; an officer extracted the arrow, but fearsome spurts of blood and hissing air came with it, and the king passed out. (James Romm, Ghost on the Throne; The Death of Alexander the Great and the Bloody Fight for His Empire, Vintage Books, 2011 at pp. 15-16.)

Leading from the front inspired a fierce and lasting loyalty among his generals and troops.

Leading from the front had another advantage: It gave him what the French called the “strike of the eye” or “coup d’œil,” the ability to discern at one glance the tactical advantages and disadvantages of the terrain and detect enemy troop movements on the battlefield at a glance. Alexander led his vaunted Companion Cavalry into battle, and riding at the front he was able to scramble when needed, sizing up both the enemy and the terrain on the spot and issuing precisely the right orders to fit the rapidly changing circumstances.

Be Empathetic to Your Colleagues

Always placing the needs of his men above his own, Alexander never asked his men to do what he would not do himself – the third leadership lesson. In 15 years of conquest, he never lost a battle.

A great example is Alexander leading his men on foot during the long and arduous march through the Gedrosian desert. During the grueling march, Alexander refused any comfort and suffered along with everyone else. Many died of starvation, thirst and heat. When his men found a little water hole and brought him a helmet full of precious water, “Alexander, with words of thanks for the gift, took the helmet and, in full view of his troops, poured the water on the ground. So extraordinary was the effect of this action that the water wasted by Alexander was as good as a drink for every man in the army.” (Anabasis, The Campaigns of Alexander 6.26.)

Alexander was aware of his men’s thoughts and feelings and had a keen sense of what they were experiencing. Even though he was their king, he did not place his own needs above theirs and suffered and celebrated along with them. Because he eschewed any comfort for himself, his men followed him to the ends of the known world.

Pictured right: Giant Statue of Alexander, Greece Thessaloniki

Alexander did not live long enough to enjoy his many victories. At one of his parties while preparing for yet another war to conquer the Arabian Peninsula, he came down with a fever and 11 days later he died on June 10, 323. The Book of Daniel recorded that “the great horn is broken,” a reference to the shock of his untimely death just shy of 33 years old. Some believe he may have been poisoned but this has never been proven.

Marcus Aurelius

The last of the Five Good Emperors and the last emperor of the Pax Romana (27 BC–180 AD), Marcus Aurelius ruled the Roman Empire for 39 years from 161–180 AD. Known as the “Philosopher Emperor,” Marcus Aurelius wrote intensely personal philosophical “exercises” and “exhortations” to aid him in his life and rule. They were so powerful and uplifting that his sheaves of notes were likely saved by his friends and admirers and kept alive by philosophers, Christian theologians and medieval scholars. Although his reign ended with his death at age 58 in 180 AD, the Meditations, as they came to be called collectively, wasn’t published until 1558, and it has been in wide circulation and use ever since.

Marcus Aurelius wrote his Meditations during bone-chilling, dark winter nights as exhortations to himself for his own spiritual enlightenment and development. They were a highly personal, inner dialogue never meant to be shared. In fact, the Greek title for the book was To Himself.

Pictured left: Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius, Rome

Although he detested war as a disgrace and calamity of human nature, Marcus Aurelius found himself personally involved in eight winter campaigns against Rome’s fiercest enemies. As commander, he personally defended the frontiers, eschewing the comfort and splendor of Rome to be with his troops. He was occupied constantly with the preservation of the Empire, as barbarians constantly tested the vast Roman borders. While at the front, he lived in a tent among his men camped beside the Danube River, and he was determined not to return to Rome until the seemingly endless campaigns were over and the Empire secure. When he returned, he was hailed a saint for his courage and strength of character.

Marcus Aurelius wrote his meditations, devoid of war recollections, as a man, not as an emperor or conqueror. He wrote honestly, sincerely, from his heart, trying to understand the chaotic events happening to and around him and to put them in context and perspective with the philosophy taught by his teachers. He attempted to reconcile the gore of war with the natural beauty he saw in the world.

Marcus Aurelius relied on this philosophy to give him strength to sustain him in life and prepare him for death. His writings ring of truth and wisdom. He wrote with no motive except to try and understand the meaning and purpose of existence. His guiding leadership principle was self-reliance and self-mastery, “It’s up to you!” (The Emperor’s Handbook: A New Translation of the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, Scot Hicks and David V. Hicks, Scribner 2002, I:16, p. 26.)

- He assumed personal responsibility for the situations in which he found himself.

- He wrote poetry amidst the horrors of war, exhorting himself to “fly with the stars in their courses, and swim among the ever-changing elements in their fluid transmutations. Imaginings like these will wash away the filth and grime of this earthbound existence.” (Id., VII:47, p. 84.)

- He trained himself to live in the moment, not the past or future: “We live only in the present, in this fleet-footed moment. The rest is lost and behind us or ahead of us and may never be found.” (Id., III:10, p. 37.)

Attitude was everything to Marcus Aurelius: “Your mind is colored by the thoughts it feeds upon, for the mind is dyed by ideas and imaginings.” (Id., V:16, p. 58.) Thoughts to him were living things, and actions the blossoms of thoughts. If we get up in the morning in a bad mood, thinking negative thoughts, chances are we will have a bad day and people will avoid contact with us because they sense the negativity around us. Conversely, if we rise in a positive, joyful frame of mind, we are likely to encourage people to have contact with us and help us get things done. We are the end product of our thoughts and the actions taken as a result of those thoughts. Thoughts lead to actions and positive thoughts lead to positive actions. He believed in humility, character and honor:

“Don’t be a Caesar drunk with power and self-importance: it happens all too easily. Keep yourself simple, good, pure, sincere, natural, just, god-fearing, kind, affectionate, and devoted to your duty. Strive to be the man your training in philosophy prepared you to be. Fear God; serve mankind. Life is short; the only good fruit to be harvested in this earthly realm requires a pious disposition and charitable behavior. To live each day as if it were your last without speeding up or slowing down or pretending to be other than what you are – this is perfection of character.” (Id., VI:30 p. 70.)

There is a great deal to be learned about leadership and personal development from this philosopher Emperor that are helpful lessons for any general counsel.

Socrates

From Socrates, we inherited the Socratic Method – a form of pure, relentless inquiry and debate between individuals with opposing viewpoints based on asking and answering questions to stimulate critical thinking and illuminate ideas. Socrates believed that truth was immanent in the world and men; to be drawn out through reasoned questioning. His interrogation method was aimed at the most general kinds of truth, the “bigger picture.”

Socrates believed in the theory of recollection: Each person contains all that is known as memory and it is the teacher’s job to assist the student in bringing out the truth that is embedded in memory. If the teacher asks the right questions and puts them to the student in the right way, the student will answer correctly and remember. In other words, we already know the truth, we just need to ask the right questions to bring it out.

The Socratic Method is the main weapon in a lawyer’s arsenal, and we all have it hammered into us in our law schools. By constantly asking questions, we avoid becoming complacent or comfortable. Creativity and ingenuity spring from asking questions and change comes from questioning everything. An inquisitive mind is a sharp tool.

Confucius

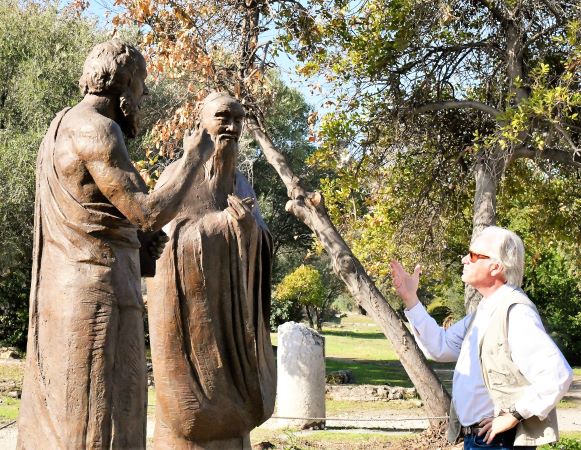

Pictured right: Stratton in Ancient Athens Agora “with” Socrates and Confucius

The Analects of Confucius (selected sayings) is among the most influential books in history. In fact, Will Durant listed Confucius as the greatest thinker of all time in his book The Greatest Minds and Ideas of All Time. The Analects is a sourcebook for governing nations and managing enterprises, to dealing with society and friends, to maintaining family and mastering oneself. Unfortunately, Confucius’ name is better known than his teachings today. He worked for cultural revitalization as a means of cultivating human feelings. Confucius taught four things: culture, conduct, loyalty and faith.

Confucius said to a pupil, “Do you think I have come to know many things by studying them?” The pupil said, “Yes, isn’t it so?” Confucius said, “I was not born knowing anything, I was fond of the ancient and sought it keenly.” (Thomas Cleary, The Essential Confucius, Harper Collins 1993, 15:3, p. 53.) In other words, he did what we are doing now, learning from the past as a guide to the future. Confucius said, “Heaven gave birth to virtue in me; what can opponents do to me.” (Id. 7:22, p. 71.) If you live an ethical and virtuous life, no one can harm you. You become bulletproof! Being ethical makes a person strong – it becomes an armor and shield against enemies.

Confucius taught that absolutely everything we do in our lives matters. He taught that whatever we have done in our lives makes us what we are when we die. And everything, absolutely everything, counts. He believed that there is an ultimate accounting at some point, a great reconciliation, a personal karma and business karma.

Conclusion

We have journeyed across time through the ancient world, yet we have but scratched the surface of the lessons the great leaders of the past have to teach relative to our own time and troubles. The truth is that our modern technology hasn’t made our jobs all that much easier or safer, or ourselves happier or wiser. We must admit that we don’t know everything and we still have much to learn.

As we’ve seen, few have faced more difficult circumstances than these ancient leaders. They regarded the many obstacles they faced as opportunities for creative problem solving. They refused to let calamities get the best of them, meeting each head-on with dignity, style and grace – and that’s what’s needed in the board room.

Now, as Marcus would say, “It’s up to you!”

Stratton Horres is a partner in Wilson Elser and has 40 years’ experience representing clients in catastrophic and high-exposure cases across the US. Please follow his travels at strattonhorres.com.