When news breaks of a plane crash, pilots Mike Slack and Ladd Sanger of Texas-based Slack Davis Sanger begin analyzing the incident before ever receiving a call from a client.

“We read up, and when we get a call two days later or so … we’ve got good insight into what happened,” Sanger said. “People come to us at the lowest point in their life and to the extent we can help them navigate that with our expertise, that makes me feel good.”

Slack launched the boutique trial firm in 1993, with nationally recognized aviation lawyer Tom Davis and his son, Mike, as founding partners. Sanger joined in 2003 after his mentor and law partner, renowned aviation lawyer John Howie, died.

Both Slack and Sanger are among an elite tier of attorneys who are experts in aviation law and whose work has made commercial and private aviation safer for the masses.

Their contributions to aircraft safety are numerous. A few highlights are:

- They settled litigation with Cessna over the 2002 fatal crash of a 208B Caravan turboprop that saw the company discontinue use of its allegedly defective pneumatic de-icing system and adopt an alternative design they proposed.

- They discovered and reported to the NTSB several defects in the design and operation of an Airbus AS350 B2 helicopter during litigation over a 2014 fatal news helicopter crash in Seattle.

- They pinpointed a performance issue with a system designed to automatically start descent of a plane when a pilot may be suffering hypoxia in litigation with Cirrus and Garmin.

- They discovered and reported that erroneous assembly instructions for the U.S. Army Chinook CH-47D twin-rotor helicopter was to blame for a 1995 crash during a test flight southeast of Fort Hood.

Amid the successes, Slack Davis Sanger has endured hard times, including the death of Tom Davis in August 2005 and the death of Mike Davis in March 2022. But through it all one motive has driven the firm to carry on: figuring out why catastrophic crashes have happened and pushing to implement solutions that will prevent them from repeating.

“One of the reasons I left NASA is because I missed helping people,” Slack said. “And here, we get to do things with technical experience and knowledge and eliminate the problem.”

The partners recently spoke to The Texas Lawbook about how their paths crossed, what aircraft they refuse to pilot or ride in based on safety records, and why their shared goals make them good partners.

From Refugio to NASA

Slack grew up in Refugio, Texas. His father was an oil industry engineer and his mother a Texas Christian University-educated pianist. When it came time for college, he left the rural community for Texas A&M University, where his father had gone to school.

“I remember the pivotal moment when I got the A&M catalog and opened to aerospace engineering,” he said. “That really appealed to me. I got infatuated reading the academic catalog of the curriculum.”

He enrolled in the fall of 1969 and joined the Corps of Cadets, at a time when many 18-year-old men like him were being drafted into the Vietnam War.

But there were signs before the academic catalog hit his mailbox that aerospace engineering would be a good fit. Like when his mother would begrudgingly agree to let him stay home from school to watch NASA’s televised launches, or when he used his younger brother’s trombone — specifically a footlong section of the slide — to build his own rocket with the aid of some gunpowder.

That launch wasn’t a success.

The rocket started off vertically but took a turn, coming close to hitting his mother.

“She was not pleased about the close call with the rocket. Then the subsequent discovery that I had damaged — sacrificed — part of the slide of this trombone did not help my case,” Slack said. “So, where was some discussion later that evening about how my rocket building probably should taper off.”

After his first year of college, he said he took an oilfield job to pay for flight lessons, a hobby he pursued on a pay-as-you-go basis until he earned his pilot’s license while he was working at NASA.

He graduated with a master’s degree in aerospace engineering from Texas A&M University in 1974 and worked as an aerospace engineer at Johnson Space Center from 1974 until 1980.

NASA decided in the 1970s to abandon moon missions, doing away with what drew Slack to work there in the first place. And the mission that replaced it — low-Earth orbit exploration — he found “not very interesting.”

He knew it was time to leave.

“The space program is starting to feel like it’s stagnating as far as the forward-thinking stuff,” he recalled thinking. “I came here for the forward-thinking stuff.”

That shift in trajectory for NASA sent Slack — who had sworn he was done with classrooms after earning a master’s degree in aerospace engineering from Texas A&M in a single grueling year — on a course for law school.

Without studying or otherwise preparing, Slack took the LSAT in Houston in January 1980 and had his test scores sent to the law schools at the University of Houston, the University of Texas and Southern Methodist University. The amount of math on the exam was surprising and encouraging, he recalled.

“I thought ‘I have a chance, I have a chance,’” he said.

He was accepted to all three schools, but the idea of moving to Austin or Dallas wasn’t appealing. He decided to continue working at NASA during the day while attending UH law school at night.

But plans changed.

“This is all very vivid because it was like every time I encountered something related to this law journey, it was a surprise,” he said.

While on a diving expedition that spring with a nonprofit group surveying shipwrecks among the coastal reefs in Belize, he met a lawyer who was serving in the White House Counsel Office of President Jimmy Carter. Around the campfire one evening, Slack mentioned he would be starting law school in the fall at UH while keeping his day job at NASA.

“He said, ‘That’s nuts,’” Slack said. “So, what we did — and this is preposterous but true — the next day we hop in a boat and this fellow drives us to Belize City and we walk into a customs office, and this guy goes ‘I’m so-and-so associate counsel with the Carter administration, I need to use your phone.’”

The man called the UT admissions office, told them to enroll Slack for the fall semester, and the rest is history. He doesn’t remember the man’s name, but Slack has never forgotten the impact he had on his career.

After a chance meeting at an airplane hangar during his first year of law school, he snagged a clerkship with Tom Davis, a nationally recognized aviation attorney who coauthored a casebook he was studying.

The clerkship spanned his three years of law school. He graduated in 1983.

“I thought he was going to turn around and offer me a job, but he said ‘You don’t know enough about how to handle a trial,’” Slack said.

So, with the aid of a recommendation from Davis, Slack said, he was hired to work with Windle Turley in Dallas, where John Howie also worked. While he was there, he represented the family of famed guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan, who died in a helicopter crash in 1990, and reached a confidential settlement.

Davis, along with his son, Mike, later became founding partners of Slack Davis in 1993.

The firm was among the first to lean in to using technology for managing and resolving cases.

“When we designed our first office, we had no law library. We had three computers,” Slack said. “That was heresy. But we were going to do it our way.”

The practice was booming and the work was fast-paced, Slack said, but in 1997 he took on the responsibility of being president of the Texas Trial Lawyers Association and his two partners became ill.

Tom Davis was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and his son Mike was diagnosed with lymphoma.

“All of a sudden I had two partners suffering and I was going to the capital as president of the Trial Lawyers,” he said. “It probably was not the best combination of events to come along for a young law firm.”

Dallas by Way of Wyoming

Sanger, a native of rural Saratoga, Wyoming, which boasts a population just under 2,000, had a childhood fascination with aviation fostered by his family’s use of planes to tend farms.

He ended up at Southern Methodist University after visits to schools on the East Coast, including Princeton University, left him feeling like the transition from rural Wyoming would be too much.

There was too much “hubbub” on the East Coast, he said, and the West Coast felt too “fancy” for the Wyoming boy.

“But it was just by serendipity, my mom, being the ever-efficient planner, said we’re stopping in Dallas on our way to Vanderbilt. We had a family friend who went to SMU … but I didn’t know anything about it,” he said. “What was going to be a four-hour visit turned into a four-day visit. And I just fell in love with it.”

He graduated from SMU in 1993 with a bachelor’s degree in finance.

While he began his college career and made his home 1,000 miles away from Saratoga, he hasn’t forgotten the community that raised him and fostered his interest in aviation.

“When I was a little boy, I would ride my bike up [to the regional airport] and get to know the pilots who rode jets — I got to know the CEO,” he said, recalling odd jobs he would do there, including washing airplanes. “I was always dressed up and respectful and inquisitive, and they took me under their wing.”

Finance and business were his focus in college, but it was his interaction with attorneys for American Airlines while he was working for AMR Combs, the general aviation affiliate of American, on a project to open a private jet terminal in Mexico that brought his postgraduate plans into focus after he expressed frustration with the pace of progress.

“I was in this conference room, about as useful as office furniture to them, and one of the lawyers said ‘We’re lawyers, you’re not. We know what’s best for the company, you don’t,’” he recalled. “At that time, I knew I was going to grad school and was thinking about an MBA. But I said law school gives you the power to never be in the situation where someone says ‘I’m a lawyer, you’re not. I know better.’”

The legal world wasn’t a complete mystery to Sanger. As a young boy, he got a taste for life in the courtroom as his parents fought a yearslong eminent domain battle against the federal government over roads that led to his family ranch.

“I was a little boy sitting in the 10th Circuit,” he said. “I vividly remember our lawyer saying, ‘You can never win against the federal government. All you’re doing is mitigation.’”

He went to law school to become a defense attorney, he said, intent on not becoming one of those guys who got a degree but never practiced law. So, he headed 200 miles north and enrolled at the Oklahoma City University School of law.

But the job market when he graduated in 1996 wasn’t great.

He couldn’t find a job.

Then, a classmate from SMU he had stayed in touch with introduced him to his father, nationally recognized aviation lawyer John Howie.

“We went to lunch and he said ‘I’m not going to hire you, but I’ve got a big case in Arizona and we’re going to try that case in four months.’”

Howie pointed Sanger to a stack of banker boxes filled with evidence.

“It was totally disorganized and he said ‘Your job is to get that thing organized,’” he said. “And I did that.”

That led to another task: a wreckage inspection in Arizona ahead of trial.

And another: schlepping charred wreckage into the courtroom during trial amid stern warnings from the judge to not damage the carpet.

“We try that case and get a $60 million verdict against Beechcraft,” Sanger said.

That sealed the deal and Sanger went from contractor to full-time employee of the firm.

He now serves on the Saratoga Airport Board, and has seen the sleepy community transform into a high-end tourist destination with significant private aviation traffic. He’s helped oversee improvement projects to the airport there, free of charge, and has secured government and state grants to fund that work.

Teaming Up

Sanger was working on a case with his colleague Howie when he first met Slack in 1999. The thing that stands out to Sanger about that meeting, almost a quarter-century later, was Slack’s shoes.

“They were exquisite alligator cap toe shoes polished to perfection,” Sanger said. “And he kept it a secret for about a year where he got those shoes from.”

Slack remembers something different.

“We were working a case with John Howie, and then all the sudden he had this high-energy young guy working for him who seemed to know a lot about aviation,” Slack said. “I heard John bragging about Ladd, but the point at which I became truly aware of Ladd’s abilities was when John got a verdict in Arizona in a Beechcraft spin case and Ladd did a significant amount of work on that.”

A so-called “flat spin” is when the aircraft spins like a Frisbee, rotates around its axis and descends vertically. In the aftermath, the aircraft looks not unlike a stepped-on beer can.

“I knew what a flat spin case was and knew how difficult they were. … Ladd was able to really do high-level work despite his level of inexperience, producing high-level work for John,” Slack said. “John didn’t fool around with fools.”

Their mutual admiration for each other’s approach to legal work came to a head on Oct. 25, 2002.

Howie told Sanger his cancer had resurfaced after remission and time was short.

“Howie asked me what I wanted to do, and I said I wanted to explore doing something with Slack,” Sanger said. “He said he didn’t have a lot of time and that he would reach out to Slack.”

Slack said the meeting that followed between the men, who had spent their careers as friendly competitors, was somber.

“[Howie] said, ‘I’m really sorry we didn’t get together on this before now.’ He said we were both smart enough to know we should have been partners doing aviation cases together but didn’t figure it out,” Slack said. “Among the things he said is he wanted me to take on Ladd Sanger as one of my attorneys. I said, ‘That’s easy, he’s a good talent and I know him and appreciate him.’”

About three hours later, Slack and Howie had reached a handshake deal on the future of the firm.

Howie died Dec. 31, 2002.

In their years together, Slack and Sanger have worked hard to make aviation safer for the masses. And lessons learned studying fatal and disastrous have shaped their own flying habits, too.

For Slack, learning about rotorcraft stability as an undergraduate was enough to make him never want to fly any helicopter. He’ll only ride in helicopters with two engines.

“I will walk to my destination before I strap into a Robinson R44 or any Robinson product,” he said. “If I’m ever in a medical situation requiring ambulance transport, I’ll go in a ground ambulance. It will not be in an air ambulance helicopter.”

Two airplanes make Slack’s no-fly list: Cessna 210 series and the V-tail Bonanza.

Sanger’s list is shorter.

“I am more adventurous than Mike,” he said. “My main two no-go machines are the Mitsubishi MU-2 and any Robinson helicopter. I flew a Robinson once and that was enough.”

Just a month after the Sept. 11 attacks, American Airlines flight 587 departed from John F. Kennedy International Airport headed for the Dominican Republic. Turbulence caused the aircraft’s tail to fall off and the plane crashed into Jamaica Bay, killing all 260 people on board.

In the litigation that followed, lawyers for Airbus blamed American Airlines and poor pilot training for the crash while American Airlines alleged a design flaw and faulty repairs were at fault.

Slack and Sanger, who represented the families of 24 passengers, were among the group of lawyers on the plaintiffs steering committee and were in Paris to take the deposition of an engineer for Airbus.

“Mike is a loads engineer, he worked on space shuttles, and the guy tries to bullshit him,” Sanger recalled. “And Mike just eviscerates the witness. You could just see and feel the tension in the room. These are the best aviation attorneys in the world, and Mike came in, this plaintiffs’ lawyer from Texas, and it just totally changed the dynamic of the litigation.”

The deposition changed the course of the litigation, and American Airlines and Airbus both contributed settlement funds to Slack and Sanger’s clients.

Another memorable deposition came in Canada, when the law partners were deposing witnesses in litigation stemming from a plane crash that happened in Guatemala. Slack asked an investigator for the manufacturer where his notes were from the scene.

The investigator said he didn’t take any notes.

Slack presented him with a photograph taken from the scene of the crash, where a man can be seen clearly taking notes amid the smoking wreckage.

“[Slack] asked what are you doing here? Taking notes? Where are they?” Sanger recalled. “He said he destroyed them. We took a break, and you know where that case went. I have a lot of stories like that.”

In other wins for aviation safety, Slack and Sanger got American Airlines to change the policy regarding how close pilots fly to thunderstorms, and handled two military helicopter crash cases that they discovered were caused by counterfeit, cheaply-made Chinese capacitors that had made their way into the circuit boards on the U.S. aircraft.

“We don’t know if it was intentional or unintentional,” Sanger said. “Instead of $1 [capacitors], they were five cents. We went into the boards and found they were failing. And as a result of that, those accidents stopped and the military re-did all those circuits.”

Their tactics to improve safety extend beyond the courtroom, too.

During litigation with Cessna over a crash stemming from a faulty wing de-icing system, they reached a monetary settlement but couldn’t move the company to implement design changes.

“But we quietly went to the FAA to get approval to make the change we were advocating for,” Slack said.

About a year later he noticed a new Cessna, outfitted with the new system. He sent a picture of it to the client.

“It all came together. I don’t care how it happened,” Slack said. “If we can bully them, and then they quietly go do it, that’s fine, too.”

Recently the firm wrapped up a case where a 17-year-old boy was severely burned and survived a crash but his father, the pilot, died. Their plane ran out of fuel while they were trying to figure out a problem with the landing gear.

“We resolved the case … but took the additional step of putting him in an arrangement with a safety net that secures his financial well-being for life,” Slack said. “We don’t finish our cases by calling a cab and handing someone a check.”

Slack and Sanger also worked to get a retrofit implemented on Robinson R-44 helicopters.

There was a flaw in the design of the fuel tank on that aircraft that was turning otherwise survivable crashes into fatal, fiery infernos.

“There were a number of those crashes where people burned alive in the helicopter,” Sanger said. “I had a lot of Robinson cases. I got to know [founder] Frank Robinson and had a cordial relationship with him — he called me his favorite villain.”

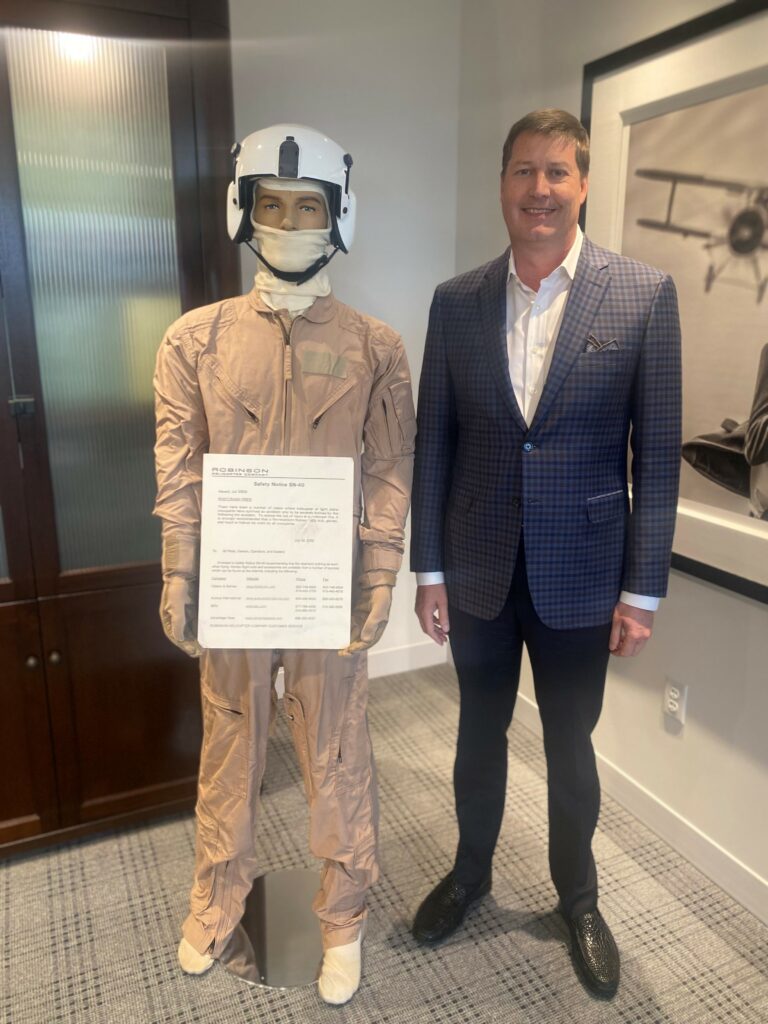

Robinson’s proposed fix for the R-44, known as Safety Notice 40, didn’t satisfy Slack or Sanger.

“It basically said you had to wear the same outfit a NASCAR driver would, everyone in the helicopter, and that was their solution to these post-crash fires,” he said.

Slack said the directive that pilots and passengers come dressed for a fire was both “stupid” and “a gift.” He recalled that one client, widow Ellen Nemec, who in 2006 lost her husband Craig in a Robinson R-44 helicopter crash in Fredericksburg, insisted on pushing for reforms.

“We said, ‘Frank, the money’s not going to do it this time,” Slack recalled. “We need to eliminate the fire problem.”

A retrofit was also being applied to another model of helicopter, but when it came to the R44, only Robinson’s personal helicopter was outfitted with the safer design.

“We negotiated a settlement and wrote into the agreement that they would immediately set up a production line to retrofit the helicopters,” Slack said. “And we also got the right of unannounced inspection for two years, so we could show up and inspect the production line and see the records of how many retro kits had been installed.”

In Sanger’s office today is a mannequin dressed in the Nomex suit Robinson previously instructed all passengers to wear, with Safety Notice 40 resting in its hands. He says it serves as a reminder of why he does this type of legal work.

“It lives right outside my office,” Sanger said. “And I’m proud of this because we have saved hundreds of lives and prevented countless injuries. It really gives you meaning for what you do, the fact that we can enhance aviation safety and make it better.”

Slack and Sanger unsuccessfully lobbied Robinson to apply the fix to helicopters that were already in use, but Robinson agreed only to implement the safer design on new-production helicopters.

Fast forward to 2012, the firm got a case out of Australia involving a Robinson helicopter. A crash and a fatal fire had happened during filming of James Cameron’s documentary, Deepsea Challenge.

Frame-by-frame footage of the incident showed the tail of the helicopter hitting the ground, which Sanger said tore open the fuel tank and engulfed the entire aircraft in flames before it hit the ground.

“It was three feet off the ground and burst into a ball of flames and [both occupants] are burned alive,” Sanger said.

Soon after that, the Australian government grounded Robinson helicopters and the company then moved to have the safer design alternative implemented to all helicopters, setting a compliance deadline of April 30, 2013.

“To this day, they have not had a single post-impact fire with that retro kit that was otherwise survivable,” Slack said. “So that solution fixed the problem.”

Besides the mannequin, Sanger keeps other reminders of the good that can come from litigating aircraft crashes.

“There was an offshore helicopter case I handled,” he said, explaining the plaintiffs, who survived, were a young couple with two children. “They were facing financial ruin, and I got them a nice recovery. And the little kid draws in Crayon a picture that says ‘Thank you for letting me stay in my house.’”

“I still have that,” he said. “When you can make that kind of an impact on people, it’s different than if you’re representing an insurance company. And I find that rewarding.”

Slack said he and Sanger “thrive” on the same kind of work, which makes them great partners.

“Finding the problem. Solving it,” he said. “These cases give us the opportunity to do that: identify the problem and use expertise not only to figure out what happened, but in many cases put in a fix for the problem that the manufacturer allowed to happen.”