When a case presents an unsettled question of Texas law, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has two options: venture an Erie guess and possibly get it right, or go straight to the state’s high court and ask it for the correct interpretation.

If the Circuit decides to ask the Texas Supreme Court for an answer via a certified question, the justices have two options: accept it, gather briefing from the parties, hear oral arguments and answer the question, or reject the question.

The last time the Texas Supreme Court refused to accept a certified question was June 5, 1991, in Hotvedt v. Schlumberger. In that case, the Fifth Circuit asked the Texas Supreme Court to determine whether the granting of a stay in California based on forum non conveniens was equivalent to dismissal for lack of jurisdiction under section 16.064 of the Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code.

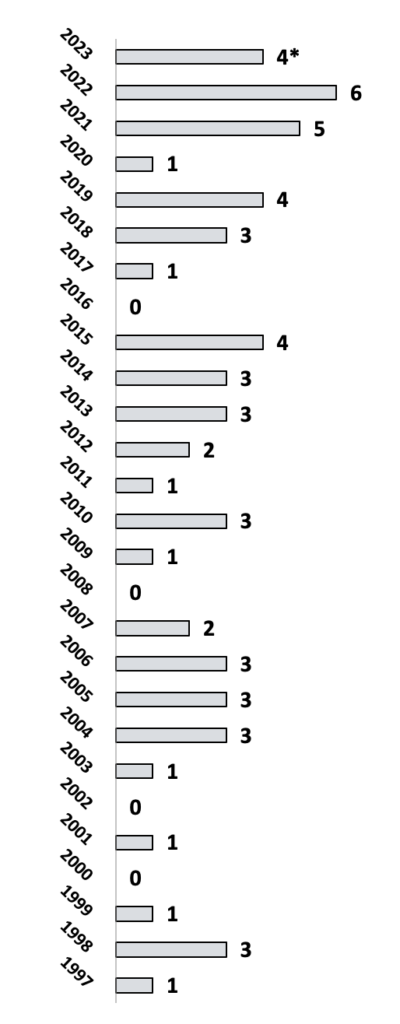

Certified Questions to SCOTX from U.S. Fifth Circuit

*Year to Date

In more than 45 years, The Texas Supreme Court has only rejected three questions, the other two coming in 1989.

“It was different back then,” Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Hecht, who’s served on the high court since 1988, told The Texas Lawbook in a recent interview. “I think there was some thinking that this is an imposition — why should we be doing the circuit’s work for them? It was kind of a negative reaction.”

But things have changed.

“Why shouldn’t we be deciding questions of Texas law?” Chief Justice Hecht said. “It’s better for the parties, the state, the judiciary and everybody.”

Over the last three years the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has sent more certified questions annually to the Texas Supreme Court than it has in decades. The recent increase has been few in number — with five in 2021, six in 2022 and four so far this year — but notable when compared to the average of 1.8 a year the Fifth Circuit had sent for the 24 years prior.

Chief Justice Hecht said accepting the questions — a discretionary decision by SCOTX — does not strain the court’s ability to decide disputes percolating through the 14 intermediate appellate courts in Texas. The average number of cases the court has disposed of each term over the past five years is 68.2.

The Texas Supreme Court has accepted more certified questions from the Fifth Circuit so far this year than it has granted petitions for review from all but one of the 14 intermediate appellate courts.

“I don’t think we would ever not hear argument in a case from the state system that we would otherwise hear because we got too many certified questions,” Chief Justice Hecht said.

There is, of course, the potential tipping point.

“Maybe if they certified 30 questions,” Chief Justice Hecht said. “But [the Fifth Circuit] follows the rules, too. And it’s got to be important to the case, and they go through and write an opinion when they send us the question saying this is why we think this case qualifies.”

Texas appellate attorneys have theories on what may be driving the recent increase in certified questions.

Some of it could be attributed to the November 2020 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in McKesson v. Doe, where SCOTUS reversed the Fifth Circuit and held it should have certified a question of state law to the Louisiana Supreme Court, said David Coale, a partner at Lynn Pinker Hurst & Schwegmann.

“But the broader message in McKesson was ‘Take advantage of this tool,’” Coale said.

The McKesson ruling could have been “empowering” to the Fifth Circuit, said Kirsten M. Castañeda, a partner at Alexander Dubose & Jefferson.

“If [the Fifth Circuit] believes that it needs to at least give the Texas Supreme Court an opportunity to speak first on something, then having had the United States Supreme Court say ‘You should do that in these close cases,’ that is a comforting permission to have,” she said.

“I don’t think that it has enlarged the standard, I don’t think it has made the Fifth Circuit more likely to certify a question in a situation where it wouldn’t have before McKesson,” Castañeda said. “But I do think, whereas perhaps before McKesson the Fifth Circuit may have wondered whether it was running afoul of the standard in a particular case, maybe that comfort level has been increased by what the Supreme Court said.”

The types of cases prompting the Fifth Circuit to send certified questions to the Texas Supreme Court could also explain the increase, according to Castañeda, who noted that many of them involve “emerging societal and technological issues intersecting with common law or statute,” as well as “political questions.”

The increase may have something to do with the makeup of the court, said Ben Mesches a partner at Haynes Boone who also leads its appellate group.

“We’ve had an influx of new judges on the Fifth Circuit, and I think there’s two aspects to that. A number of them are former state court judges. … [A]nd I think you also have a group of judges reluctant to be making state law on novel or first impression questions, particularly when there are state statutory provisions at issue that haven’t been construed, or state constitutional provisions that haven’t been construed,” he said.

And there are guardrails to prevent a potential tipping point on the number of certified questions from being reached, Mesches said.

“[The Fifth Circuit] is exercising quite a bit of judgment in terms of what they send over, and they’re cognizant of what the ask is and that it does take resources from the state court,” Mesches said. “If there’s an issue that’s going to come up again, it’s much better to have resolution and know what the law is than sort of guess and lurch your way through it.”

Some “judicial modesty” could be factoring into the trend as well, said Christopher Kratovil, a member of Dykema. By certifying questions rather than venturing an Erie guess, the court is making a “forthright acknowledgment that the Fifth Circuit is not the final authority on questions of Texas law.”

“That’s consistent with [the Fifth Circuit’s] reputation as a conservative court that tries to engage in judicial restraint,” he said. “It’s different, perhaps, than we’ve seen from other federal courts … where a federal confidence — if not a federal arrogance — weighs in favor of Erie guesses. It’s judicial modesty, it’s judicial restraint, it’s a form of judicial conservatism we’ve come to expect from the Fifth Circuit.”

Kratovil said given the “comity and goodwill” that currently exists between the Fifth Circuit and the Texas Supreme Court, it’s unlikely there’s a decrease in the trend anytime soon.

“It’s a safe assumption given the Chief Justice [Nathan Hecht] and the Chief Judge [Priscilla Richman] are spouses,” he said. “There has to be an upper limit on the number of questions, but I don’t know what that number is and I don’t know we’re there yet.”

Anne M. Johnson, an appellate partner with Tillotson Johnson Patton, said when she noticed the uptick she saw “an alternative pathway to the Texas Supreme Court.”

When compared with the number of petitions for review the Texas Supreme Court has granted from the state’s 14 intermediate appellate courts this year, the alternative pathway comes into focus:

- First Court of Appeals, Houston – 2

- Second Court of Appeals, Fort Worth – 1

- Third Court of Appeals, Austin – 4

- Fourth Court of Appeals, San Antonio- 2

- Fifth Court of Appeals, Dallas – 3

- Sixth Court of Appeals, Texarkana – 0

- Seventh Court of Appeals, Amarillo – 0

- Eighth Court of Appeals, El Paso – 3

- Ninth Court of Appeals, Beaumont – 2

- Tenth Court of Appeals, Waco – 0

- Eleventh Court of Appeals, Eastland – 0

- Twelfth Court of Appeals, Tyler – 1

- Thirteenth Court of Appeals, Corpus Christi- 0

- Fourteenth Court of Appeals, Houston – 5

“It’s very difficult to get one of the special spots on the Texas Supreme Court’s plenary docket,” Johnson said. “If you’ve got diversity jurisdiction and an important issue of Texas law, maybe your pathway is through the federal courts. … [L]itigants have to take notice of this as a potential pathway of getting to the Texas Supreme Court.”