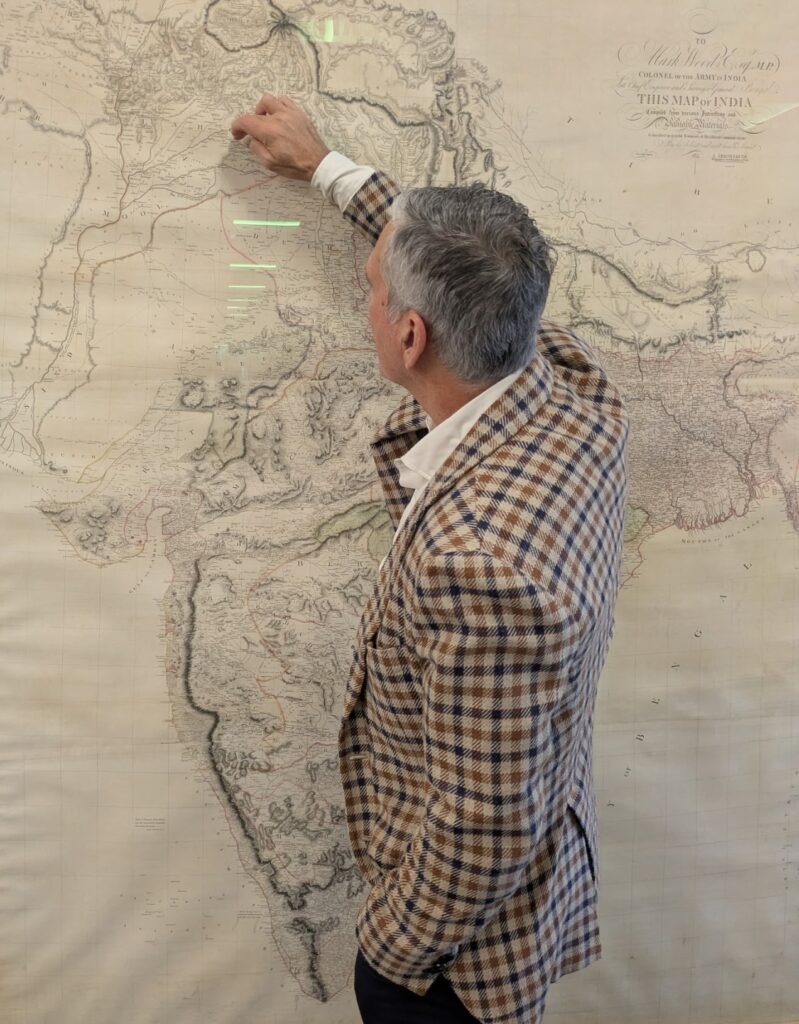

In his corner office in downtown Houston, history hangs from every wall.

You don’t just see the maps. Centuries call out as empires rise (and fall) with each step you take in Joseph Ahmad’s office, where the past is still very much alive.

The collection of maps bleeds out into the hallways of the skyscraper floors that the law firm Ahmad, Zavitsanos & Mensing occupies, jockeying for wall space alongside other works of art.

Wall space for Ahmad’s extensive collection of more than 100 maps is so insufficient that he’s got a stack waiting to be framed behind his office door, some residing at the homes of close friends, and another still hanging in the map store in River Oaks, where he purchased it.

Drawn by John Mitchell in 1755, the map depicting British and French dominions in North America is a 7-and-a-half-foot-by-5-and-a-half-foot behemoth that would require renting a box truck to move it and potentially buying a new house to display it. So, it has remained in the store for the past five years.

The real estate on the walls of his second home in Vermont is equally scarce. And at home, his wife has issued a moratorium: no more maps.

“My wife, unfortunately, is not quite as passionate about maps as I am,” Ahmad said. “She would like a little more variety at home.”

The collection’s range is vast.

Some of the maps are from the 1400s and 1500s and are the works of world-famous cartographers, while another was drawn by a Japanese girl during her time in an internment camp in World War II.

The most expensive piece cost Ahmad $115,000, he said, and is displayed at his home in Houston: a map of Jerusalem from 1486.

Before maps, Ahmad fixated on other things. As his law partner John Zavitsanos, who has known him since the two attended Michigan Law School in the mid-1980s, explained, he first recognized the intense interest and attention to detail he still associates with Ahmad because of toaster pastries.

“You know, he’s not an addict per se, but he has those, kind of, addictive tendencies. Like when he latches on to something, he’s all in. It started in law school with Pop-Tarts,” Zavitsanos said. “He was into Pop-Tarts, and then it became pizza, and then shrimp and then for a while there, it became wine. And he’s got, I’m guessing 3,000 to 4,000 bottles of wine. … And then it was rugs for a while.”

The first time the lawyers met each other, Ahmad told Zavitsanos he had gone to high school in Tennessee.

“And he said there’s a big Scotch-Irish contingent there,” Zavitsanos said. “And that was like, the first thing he told me. The guy knows more about every country in the world than anyone you’ve ever met. He will tell you what the capital was 20 years ago and what it is now. He’s always had this weird … savant kind of thing with geography.”

But what led Ahmad to begin collecting maps? It was an intersection of many interests: history, politics and geography (which he said is his best subject in Trivial Pursuit). And timing was key. Ahmad’s interest in map collecting coincided with the rise of the internet in the early 1990s, turning what used to be a hobby for professors, museums and a few well-moneyed collectors into something more accessible to the masses.

“I’d always been interested in maps, but I didn’t know it was something that people bought,” he said. “It was crazy to think you could buy something, even from the 1700s. And then you get into it and it’s like, not only have you got [maps from] the 1700s, but with a little more money you can get maps from the 1600s, and a little more money you can buy from the 1500s.”

Zavitsanos, who launched AZA with Ahmad in 1993, said it wasn’t immediately clear to him that his friend’s new all-in obsession was maps.

“He doesn’t announce it when he’s changing, you just start seeing it slowly,” Zavitsanos said. “So, then all of these, what I thought were these kind of shitty maps start showing up all over the office. I thought they were Xerox copies or something.”

The firm started running out of wall space.

“I’m telling him like, dude, these stupid maps. We’ve got to take them down because we need the space for artwork. These are photocopies,” Zavitsanos said. “And he’s like, no they’re not.”

Ahmad then explained that one of the maps outside Zavitsanos’ office was drawn by a soldier who landed on Omaha Beach during World War II and was tasked with creating a map of where the enemy was located to save the lives of the soldiers who would come after him.

Ahmad also pointed Zavitsanos to the map drawn by the child in the Japanese internment camp and led him to another map in the office that accompanies a letter penned by Gen. Sam Houston after he defeated Gen. Antonio López de Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. Houston explains he’s obtained Santa Anna’s spurs and asks what he should do with them.

“Every one of those maps has a story like that, but of course nobody knew it,” Zavitsanos said. “And so when we got into this argument about wall space and he starts telling me about some of these maps, I’m like, ‘Why didn’t you tell anyone about this?’”

The firm has since hired an art history major from the University of Houston to create placards detailing the backstory for the dozens of maps throughout the office to help passersby appreciate their historical significance.

While the fervor with which Ahmad goes about his map collecting may be hard to match, it isn’t particularly unusual that a lawyer, specifically a trial lawyer, would be interested in the hobby.

“You can see throughout history where maps were used as propaganda, or another way of saying they were a tool of persuasion,” Ahmad said.

His favorite map in the collection illustrates that very point. It’s an 1816 map of the United States drawn by John Melish and was the first map to show the borders of the fledgling country extending all the way to the Pacific Ocean, visually depicting the idea of Manifest Destiny decades before it became a rallying cry.

“A lot is revealed through maps. They show a viewpoint of certain people at a certain point in history,” he said. “[The Melish map] shows a view that’s important politically and historically.”

History repeats itself, of course, as Ahmad noted President Donald Trump’s desire that maps begin referring to the body of water that carves out Texas’ southeastern border as the Gulf of America.

“You can see throughout history where maps were used as a tool of persuasion, and map makers employed those tools of persuasion,” Ahmad said, drawing parallels to the visual tools he employs during jury trials. “There’s a strong correlation between maps as a tool of persuasion and what trial lawyers do. Because, of course, we’re trying to persuade.”