What do a monkey, two chickens, a duck, an alligator and a dog have in common with a beaver? Quite a bit if you ask Buc-ee’s, the popular convenience store and gas station that has earned a reputation for aggressively defending its trademarks in federal court.

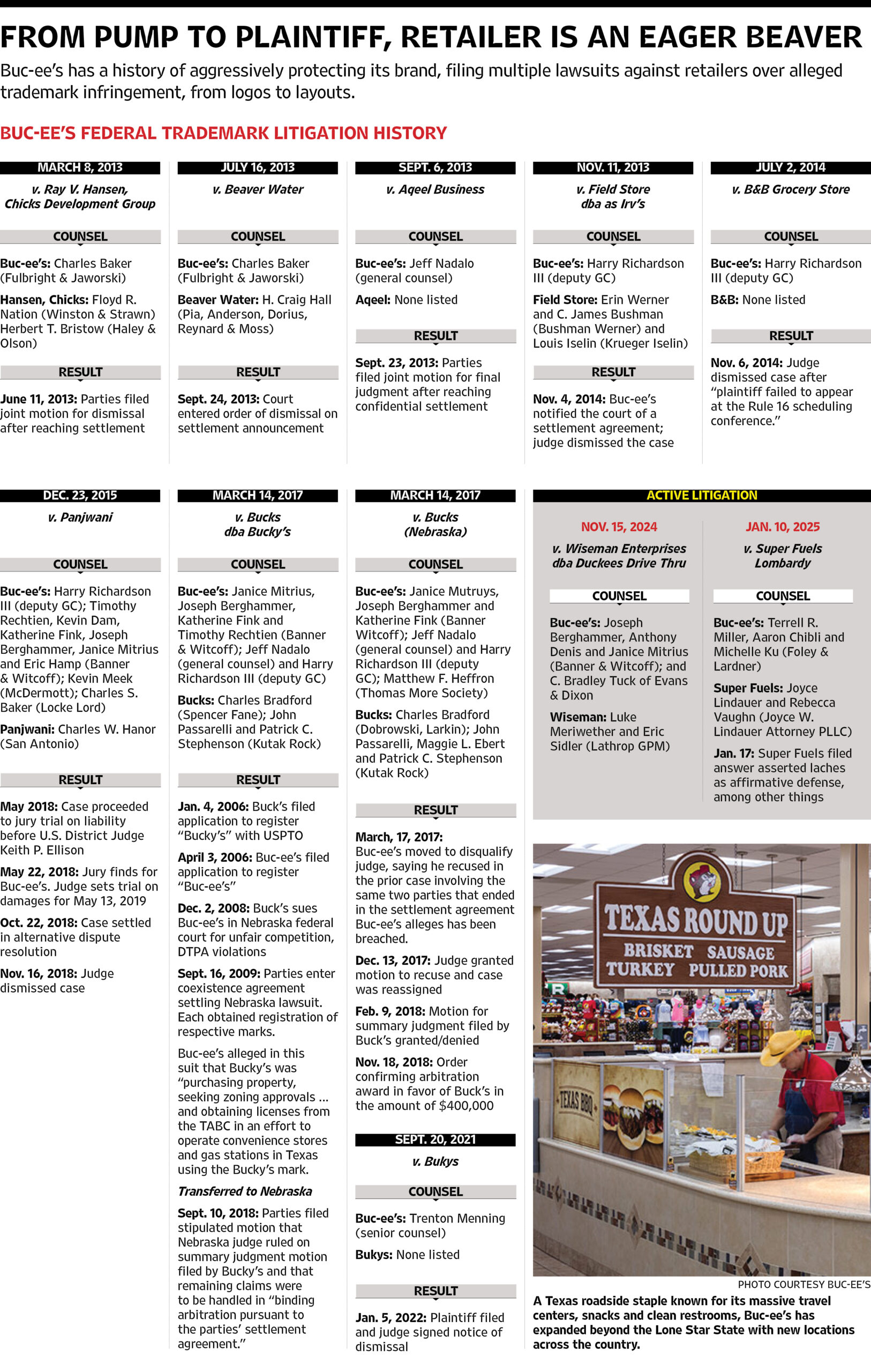

Buc-ee’s has turned to the federal courts 10 times over the last 12 years accusing companies, usually other gas stations and convenience stores, of infringing trademarks covering the logo and name the company registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in 2007 and 2010, respectively.

The Texas chain, known for an abundance of gas pumps, clean restrooms and all sorts of merchandise and snacks branded with its friendly cartoon beaver, has cultivated a devoted customer base. It has also inspired copycats, like the beaver-branded Buk-II’s Super Mercado in Matamoros, Mexico, or the gas station and car wash calling itself Buc-ee’s in Amman, Jordan.

Jeff Nadalo, who has served as Buc-ee’s’ general counsel since 2012, just before the company’s trademark litigation battles began, told The Texas Lawbook Buc-ee’s has “invested heavily in innovation across the company to provide the best quality products and experience for our customers.”

“Buc-ee’s has not remained idle spectators while others infringe the intellectual property rights that Buc-ee’s has worked so hard to develop,” he wrote in an email. “While we do not comment on pending litigation matters, we have a clear history of successfully challenging unlawful infringement.”

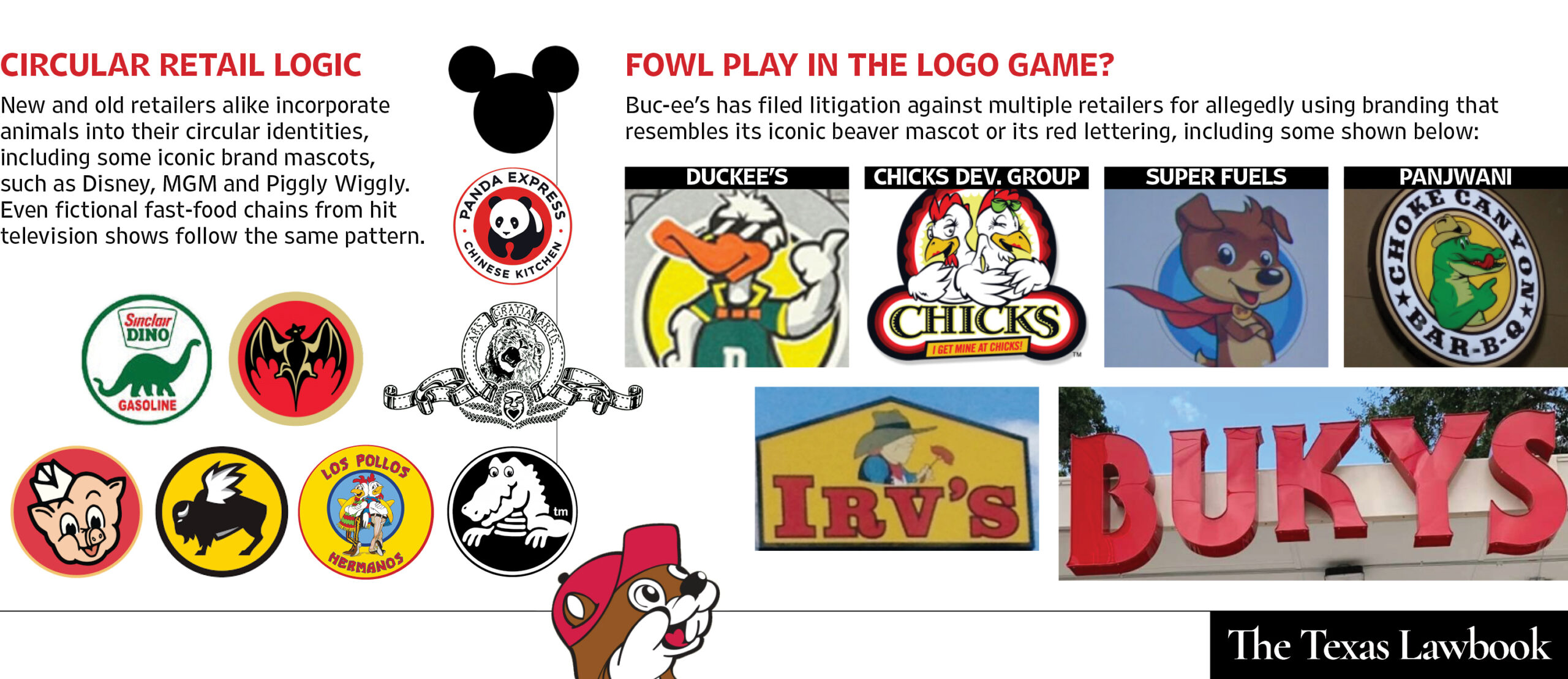

Most recently, the operator of two gas stations in Dallas that are branded with a cape-wearing cartoon dog logo (which appears to be the same image designed by an artist in Singapore and available for purchase on a stock visuals site) has found itself in the beaver’s crosshairs. And a few months before that, it was a drive-thru liquor and convenience store in Missouri named Duckees and its logo featuring a cartoon duck wearing sunglasses that drew a lawsuit.

While those two fights are still being litigated, most of Buc-ee’s trademark infringement lawsuits have settled, with defendants agreeing to change or remove logos, but one was decided by a federal jury in Houston in 2018.

In that case against Amjad Panjwani and his Choke Canyon Travel Center and Choke Canyon Bar-B-Que restaurant, jurors agreed that the company’s cartoon alligator wearing a cowboy hat, set against a yellow background and inside a circle, infringed Buc-ee’s trademark.

“My initial thought is that is why you never want a jury trial in a trademark case,” said trademark attorney Josh Gerben of Gerben IP in Washington, D.C. “I think that that is a great example of why a defendant really doesn’t want to take a case to trial and why a lot of these cases probably settle. A trial like that could easily cost that defendant $1 million in legal fees, and probably more, and you also can spend all that money, lose and still change your logo.”

Choke Canyon has since rebranded with a logo featuring a cartoon cowboy set against an orange background and inside a circle. In an interview with The Lawbook shortly after that win, Nadalo said Buc-ee’s “go[es] out of our way to let opposing counsel know that we are willing to go all the way to trial.”

Jason S. McManis, who heads the intellectual property group at Ahmad Zavitsanos & Mensing, said the argument that won the day for Buc-ee’s in that trial was more nuanced than it may first appear.

“Choke Canyon wanted to make the defense ‘it’s an alligator, not a beaver,’” he said. “It’s about more than just the logo. It’s about the whole feel of the logo, the name, the shape of the store, the type of store that it is. So if you actually look at the complaint that was filed in that case, it has pictures of the store. Yeah, it’s an alligator, but the shape of the store is almost identical to a Buc-ee’s. And all those things taken together make [Buc-ee’s] distinct.”

While it’s arguable that the differences between a cartoon alligator and a cartoon beaver are vast, some of the logos Buc-ee’s has accused of infringing its marks have been a much closer call, like the gas station and convenience store in Sugar Land named Bukys or the Nebraska-based gas station and convenience store named Bucky’s.

As Gerben explained it, those who own trademarks have a duty under federal law to “police the marketplace.”

“Why would Buc-ee’s take this kind of action? It’s not an identical logo, so why would they care?” Gerben said. “If a trademark owner allows a lot of similar trademarks to exist or register, then it dilutes the value of their registration. Think about drawing a big zone of protection around the trademark. The reason you would do policing is to increase the elbow room, the zone of protection.”

McManis agreed, but used different imagery to describe the litigation goals of Buc-ee’s.

“In the trademark enforcement realm, it’s somewhat of a game of whack-a-mole for someone who owns a mark,” he said. “I think Buc-ee’s has taken a relatively aggressive approach in filing these lawsuits, but they’ve been successful. The strategy has worked for them from a business perspective, but they’re playing the same game of whack-a-mole everyone else is.”

The purpose of federal trademark law, Gerben said, is not to protect the company, but to protect consumers from being confused about who they’re doing business with.

“While the alligator is, arguably, a much different animal, in this [most recent] case, the dog is brown,” he said, noting it’s the same color as the beaver. “People who think those two logos should coexist aren’t wrong. But the fascinating thing about trademark cases is they’re very much decided on a case-by-case basis.”

McManis expressed reservations that, if the case went to trial, Buc-ee’s would be able to convince a jury consumers would be confused by Duckees, but he said their claim for trademark dilution is a stronger one in that lawsuit.

“One issue Buc-ee’s faces is, the more famous your brand is, the harder it is to show someone is confused by someone else,” he said. “There’s all kinds of Coca-Cola knockoffs in the grocery store, but everyone knows the real can. … The strength of their brand is a great fact for them, but it can cut both ways when proving confusion.”

Finances can make all the difference in the outcome of trademark litigation, Gerben said.

“As with much of the legal system, it favors litigants that have the most money. It’s very expensive to prosecute or defend, and very rarely can someone get their attorney fees back,” he said. “So the challenge any company has going against Buc-ee’s is the resources.”

“And that’s, unfortunately, part of the inequity that exists in our legal system.”