In 1980, my parents emigrated from South Korea to the United States for a better life – one filled with promise and opportunity. Like many immigrants at the time, they came to the states with very little and worked extremely hard to provide for their family.

For 30 years, my mother owned a laundromat located in a majority Black neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina. As the area gentrified and became majority white, she pivoted and turned her store into a dry cleaning and alterations business to adapt to her prospective customer base.

My father held many different jobs and would often part ways with employers due to cultural and language barriers.

As a result of the struggles they faced, my parents urged me and my sister to keep our heads down and work hard so we could be successful. They wanted a better life for us, and they believed that conformance was the best way to achieve success. What they did not know, however, is that the goal of full assimilation was impossible to achieve. They also could not grasp that even if accomplished, perhaps assimilation should not have been the goal – that value in culture/heritage was more important in shaping what I had to offer, not the other way around.

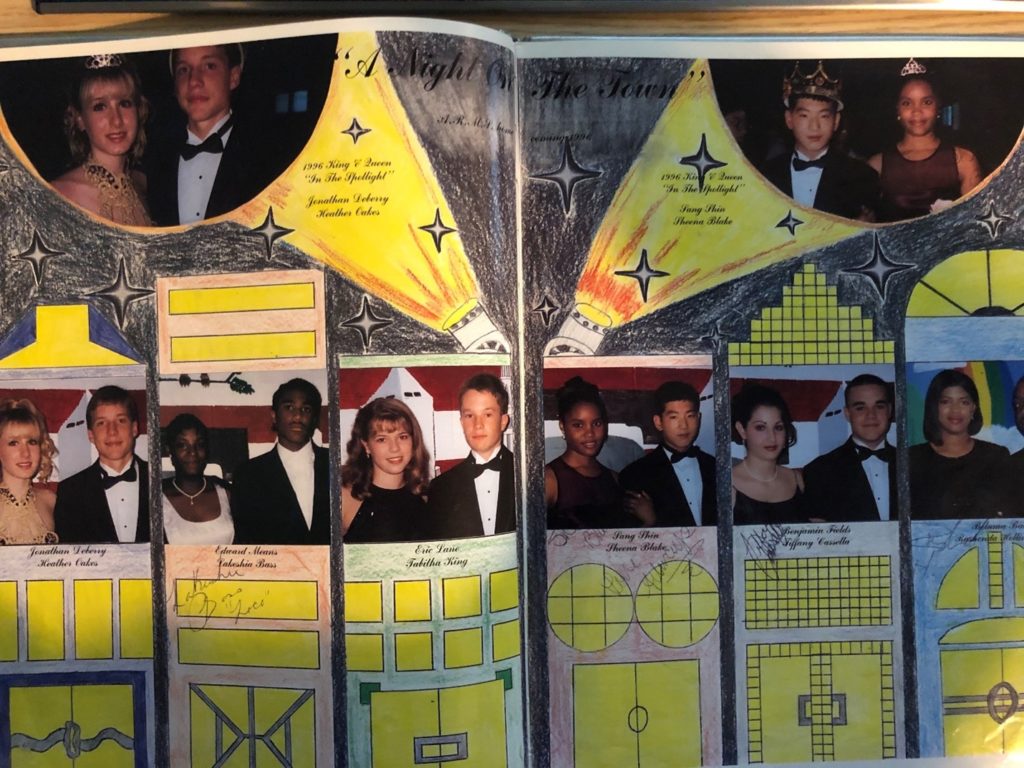

To understand my experience as an Asian American growing up in North Carolina, I have to rewind to 1997, when I was in ninth grade. Below is a picture from the school’s yearbook that featured our Homecoming Court. As you can deduce, there were two homecoming kings and queens, and yours truly was named king … of the “minority court.”

In 1997, Sang Shin (upper right corner) was named King of his school’s “minority” Homecoming Court.

Back in 1997, this was normal and was often understood as ensuring both black and white students were able to be king and queen. In fact, the school system was still working through school integration, and in elementary school I was often transported to schools more than 45 minutes from my home.

While I was happy to be considered to be on the court – let alone win – not everyone shared my enthusiasm. Many of the Black students expressed frustration that a non-Black student had won, while the white students perceived it as obvious that I would be a member of the minority court. Interestingly, that year the “Black court” and “minority court” were used interchangeably. Suffice to say, I felt unwelcome on either side.

Growing up, I often felt this tension – as if I did not belong to any community. Not many people looked like me. I was not accepted as white but I was not considered a minority either. Looking back on that experience, it still resonates with me and is quite representative of my personal struggles with identity.

There is a false notion that all Asian Americans are privileged and that their parents work hard to pay for tutors and SAT prep courses so that their children can excel in high school and get into prestigious universities. This did not apply to me, as my parents could not afford to provide those opportunities. I spent many hours helping out at the laundromat, supporting my parents at their jobs. As a result, my grades suffered. I knew I needed help, and I also knew that it was up to me to pave my own path.

Given that my credentials were unimpressive, I was not initially accepted into my alma mater, the University of North Carolina. However, that didn’t stop me from “lateraling” there the next year. I later enrolled in Charlotte School of Law, which is an unknown and unranked law school but was the only one in the area that offered a night program. For three-and-a-half years, I balanced a full-time job with nighttime courses, boasted a fair GPA and started the Asian American Law Students Association at the school. Yet, upon graduation, I applied for many of the same jobs as my peers but did not receive a call back.

Despite this, I remained determined to become a lawyer, so I relocated to Houston in 2012 to work at a local immigration boutique firm. It was in Houston – the most culturally rich and diverse city in the nation – that I found a sense of community and belonging.

When I first moved to Texas, I wanted to get involved with a professional network, and the Asian American Bar Association of Houston was the first one that came to mind. It was created for the common purpose of community and to serve the needs of the Asian American community, which is what drew me in. Over the course of 10 years, I have had the pleasure of serving on multiple committees, was named president and am now Chair of the Board of Directors, a role I have proudly held since 2019. It is through my participation in the AABA of Houston that I am able to connect with fellow Asian American attorneys and help those who experienced similar obstacles in life.

It was after I lateraled to Jackson Walker in 2019 that I was able to grow even further as a professional, develop my practice and, more importantly, grow my voice and platform, especially to those who may have had circumstances and experiences that prohibited them from reaching their full potential. I am thankful to Jackson Walker for believing in me and allowing me to represent them.

My upbringing – as an immigrant who grew up in a place where there wasn’t much cultural diversity or support – inspires me each day to work with the AABA of Houston to create opportunities for Asian Americans whose paths to success may resemble my own – unconventional and shaped more like a winding road. I am so proud that the AABA of Houston is working hard to make an impact so that individuals like myself can use our experiences to help our community and to provide the support that future generations need to succeed.

Sang M. Shin is a partner in the Business Immigration & Compliance practice of Jackson Walker’s Houston office. Mr. Shin serves as chair of the board of directors of the Asian American Bar Association of Houston, a trustee of the Asian American Bar Foundation of Houston, the secretary of the Asian Pacific Islander Section of the State Bar of Texas and is a council member of the Immigration Section of the State Bar of Texas. In honor of his contributions to APIS, Mr. Shin was recognized in 2020 with the Best Under 40 Award.