Joshua Harris in action at Morehouse College

My story starts back in the early 1960s, when my grandfather, James Allen, was recruited to become a skycap at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. Upon his arrival, he was captivated with the Seattle real estate market, enticed by the potential he could see in the future of real estate.

He told me he saved a large portion of his discretionary income and scouted out properties to buy. He ended up acquiring a small portfolio of homes in the Madrona area, which today boasts million-dollar homes. It ended up creating passive income for him for over 50 years and exploded in value as the real estate market in Seattle became ever frothy with the development of behemoths like Amazon and Microsoft.

My grandfather and grandmother valued education and believed that wealth creation is inextricably intertwined with education for minorities in this country.

My grandmother was an elementary schoolteacher who was hyper-focused on my mother’s education and, once my brother and I came along, by extension, our education. My grandmother also was very intentional about exposing her grandchildren to all the culture, arts and sights that Seattle and Washington had to offer.

The actual value of the intersection of education and exposure was apparent to me when I was interviewing for a summer associate role at Seattle-based Perkins Coie.

During the interview process, it was immensely valuable that I was conversational about all things Seattle, from the Seattle Art Museum to the Madrona neighborhood. Besides having a clear Seattle narrative and finding commonalities with interviewers, I had the educational credentials to support an offer into Perkins Coie’s summer program, which materialized into a valuable growth opportunity for me both professionally and socially.

My grandparents’ story is instructive because it instilled in me the importance of weighing short-term and long-term potential, a valuable lesson because it highlights the importance of being thoughtful about how near-term decisions can impact future generations.

My dad taught me how to deal with adversity, which he struggled with throughout his life. As a young boy in Philadelphia, he focused on education as his pathway for a better life.

Education and hard work, which was instilled in him by his mother, put him on the path to become a 30-year veteran of Ford Motor Company in legal roles of increasing responsibility. My father’s life experience profoundly impacted the lessons that he taught my brother and me growing up. One of the most important was to stay focused and plan how to overcome whatever adversity life presents.

One of my most memorable moments of adversity occurred in high school. I, as a sophomore, was competing at Detroit Country Day School, where I had just transferred, to be the starting quarterback.

All spring and summer, I was narrowly focused on that goal. I performed at a high level throughout fall camp and felt I was running away with the starting QB position. After fall camp, I was named the starter and was excited about the first game.

I was stunned to learn that my competitor for the quarterback position would start the first game because he was older and “deserved a shot.” This was the first time in my life that it became apparent to me that internal politics inside of structures sometimes can be more important than being the most talented and prepared.

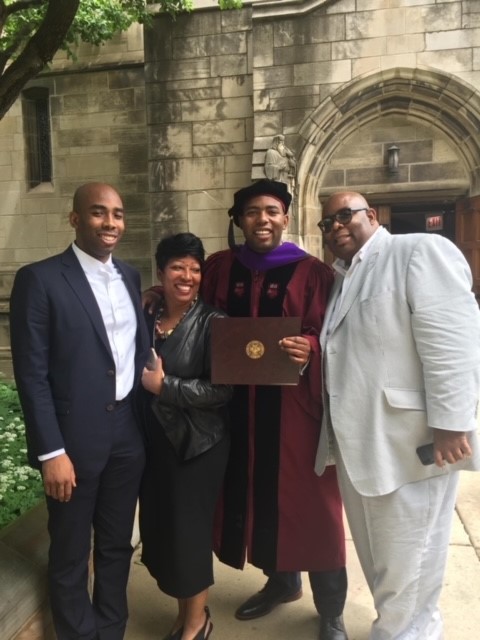

Graduation 2018 at University of Chicago Law School: (From Left) brother Allen Harris, mother June Harris, Joshua, father John Harris

At that moment, I felt at a crossroad, and my resolve was challenged. The decision was either to confront the adversity, put my head down, keep working and take advantage of my opportunity when presented to or run from the adversity and transfer to a different high school.

After counseling with my family, I decided to put my head down and keep preparing myself as if I was the starting quarterback. Sure enough, early into the first game, Coach Dan Maclean (one of the most decorated high school football coaches in Michigan history) called my number, #8. I ended up leading the team to a win and on to the state championship that season.

Even more than overcoming adversity is the truthfulness of the adage, “out of crisis comes opportunity.” Often this is used to discuss investment decisions. In my case, it involved my mediocre LSAT scores as I was graduating from Morehouse College. A decorated student-athlete, I found my admissibility to a top-tier law school was at risk.

But an excellent opportunity presented itself. Washington University School of Law in St. Louis was dealing with a dwindling number of black applicants in my application cycle as a direct result of the Ferguson unrest. I was able to capitalize on that situation to win acceptance to law school there.

I received a massive amount of support from the faculty, students and administration, which propelled me to be a successful law student. More remarkable, after my first year, all those groups supported my decision to transfer to the University of Chicago.

The lesson for me was that sometimes the best opportunities present themselves as a direct result of a crisis.

My background highlights a small number of important lessons that I believe have a powerful message for the diversity and inclusion conversation concerning law practice.

First, law firms and companies should view diversity through a lens that their near-term decisions can have a meaningful and lasting impact on future generations.

Second, law schools should focus on preparing marginalized minorities educationally and experientially so they can be prepared to thrive in post-graduation employment.

Third, marginalized minorities should come into the practice of law with their eyes wide-open that they will have to overcome adversity to be successful. And finally, given the current state of law, marginalized minorities have limitless opportunities to diversify the law and attain success moving forward.

Currently, one of the biggest challenges in the law from my perspective is the lack of diversity, especially concerning marginalized minorities. This issue is pervasive and rears its ugly head for law schools, law firms and corporations.

The interplay among those three parties is evident. Law firms provide financial support to law schools, and corporations financially support law firms. In both contexts, the entity being supported emulates the ethos of the party supporting it.

Put differently, most law firms emulate the ethos of their clients, and most law schools emulate the ethos of their largest donors, which in most cases are law firms or titans of industry.

Accordingly, it is not surprising that most equity partners at law firms, tenured professors and deans at law schools, and C-suite executives and general counsels at companies all share commonalities, which is that they are white (and more specifically, men). Ultimately, the lack of a critical mass of marginalized minorities in law schools, law firms and corporations is at the heart of the law’s diversity and inclusion problem.

This lack of diversity and inclusion in the legal space is emblematic of “the chicken or the egg” paradox. The trouble in identifying the true cause and effect of the lack of diversity in the law is highlighted by the commonly offered excuse of too few diverse and qualified lawyers.

However, the lack of diverse and qualified lawyers is partly (and arguably in large part) due to the interplay between three of the key organs of the law itself, which are law schools, law firms and corporations. Accordingly, law schools, law firms and corporations each have a specific role to play in diversifying the law.

From a law school perspective, the central focus should be increasing the applicant pool and reconceptualizing the way law schools compare themselves from a ranking perspective.

Law schools have already taken a step in the right direction on increasing the applicant pool by moving away from only accepting the LSAT, and per my count at least 46 law schools currently accept the GRE for admissions. Bold moves like moving away from just the LSAT, which has been around since 1948, shows that law schools can be creative in increasing the applicant pool.

However, there is still more work to do to ensure that incoming classes at law schools are sufficiently diverse (especially schools at the top of the rankings). The focus on metrics (LSAT score and GPA) is important, but I would propose that law schools have a carve-out for a certain percentage of incoming classes, which is not factored into their averages for ranking purposes.

I believe that I am living testament of someone who can perform at a top-4 law school with a mediocre LSAT score, which led to my graduation in the top 25% (based on historical averages of GPAs). Accordingly, I cannot help but think that if other minority applicants have the doors to prestigious law schools opened to them (with the proper support) they can be successful as well.

From both a law firm and corporate perspective, I believe the goal of increasing diversity really should be narrowly focused on diversifying the top of the structure (i.e., equity partners, C-suite executives and general counsels) through purposeful hiring, development and retention programs. In my experience, even the corporations and law firms that are at the forefront of diversity and inclusion are still very homogenous and white at the top of the structure.

The ability to change that is truly 20 to 30 years away but achievable with focused initiatives by current leadership.

Joshua H. Harris is a commercial litigator in Houston with Ahmad, Zavitsanos, Anaipakos, Alavi & Mensing, P.C.