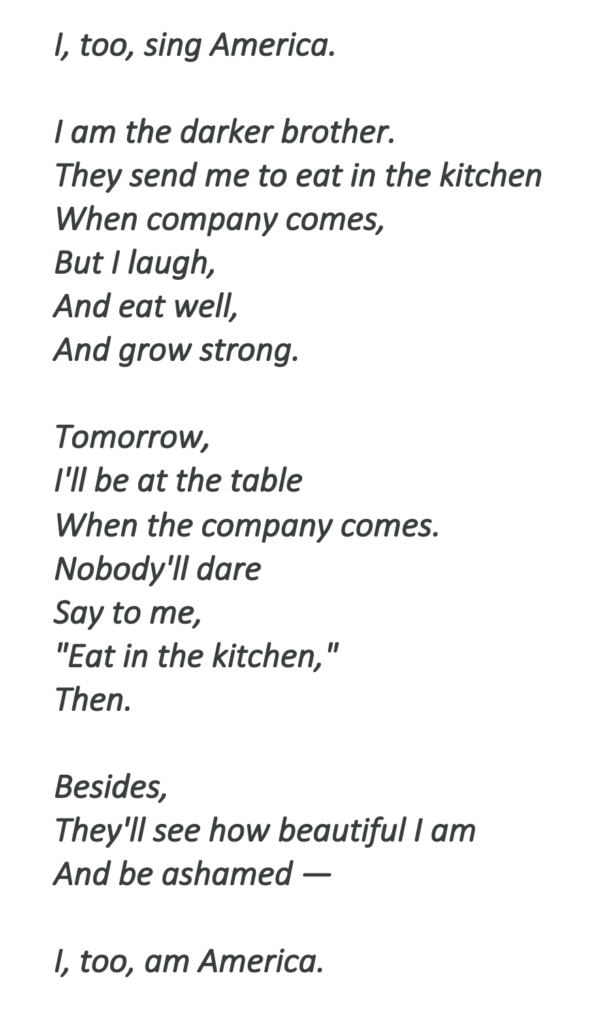

In many ways the poetry of Langston Hughes, such as his 1926 masterpiece “I, Too,” has defined my life and my determination to pursue a legal career.

As a child I slapped a hand across my chest and pledged allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. My eyes were too naive to see any differences between me and my fellow classmates. My heart was too big and incapable of understanding the shame I felt by being told I was too dark, my hair too nappy or my lips too big. My little impressionable mind could not fathom the humiliation I experienced while being circled on the playground by a 5-year old white boy calling me “nigger-brown.”

I often dismissed any feelings of hurt, burying them deep into a realm of unconsciousness never to be resurrected. I was too young to understand why I was treated in such a way just for being me. I came to the realization that I was different, and my difference somehow made me inferior to others.

As I grew older and placed that same hand over my heart, words such as “one nation,” “indivisible,” “liberty” and “justice for all” became harder to understand. I wasn’t so sure those words applied to me. The insults of that little boy slowly developed into a perpetual cadence in my thoughts. I wanted so badly to believe that the words I uttered meant something for people like me.

“They send me to eat in the kitchen but I laugh and eat well and grow strong.”

It was in ninth grade that I decided to become a lawyer. I wrote poetry for friends desperate to save their teetering high school flings and fell in love with the power of words and the art of persuasion. Little did I know that those poems, albeit far from the legal briefs I write today, were my launching pads into real advocacy. Soon, my focus shifted to seeking justice for those I felt were wronged or singled out, usually kids who looked just like me. I was pained by the sight of a teacher sending a black classmate to the principal’s office while ignoring the white classmates who were equally guilty of disruption. I had a choice to be remain silent or to speak out. I chose the latter. Silence is never neutral. It picks a side.

The Newsome Family

My parents always encouraged me to see opportunity rather than opposition. I refused to let the systems of the world define me or box me in. Education became my saving grace. I realized there may have been limitations around me, but there were no limits within me. I had the ability to learn. Being excluded from many tables did not stop my growth.

I was determined not to let growing up in a predominantly white school and town, or the fact that I did not know a single lawyer, distort the picture of what I could be. I researched every article I could find on becoming a lawyer, purchased as many resources as I could afford and did the work necessary to get into law school. I was nobody’s victim or charity case.

While in law school, I decided to avoid the path of competing with my fellow comrades. Seeing others as a threat against my progress and my potential only perpetuated separation. Competition, while entertaining in the sports arena, often breeds inferiority, feasting on our differences rather than our similarities. I wanted my differences to be welcomed rather than feared or opposed. So, I turned inward rather than outward. I became my biggest competition, my biggest critic and my biggest champion.

“Tomorrow, I’ll eat at the table …They’ll see how beautiful I am.”

Tomorrow is unchartered territory that keeps us all in a state of hope — hope that it will be better than today. This is the hope I carried while encountering racism, discrimination or implicit bias from elementary school until now. I had to believe that the world could change and that I would be a part of that change. I had faith that one day I would have access to the same tables of opportunities as anyone else, despite my race or gender, and that I would be accepted for who I am.

But such hope is not blind. I had to realize that I had something to offer that no one else could: myself. Graduating summa cum laude, participating in two federal clerkships and now working for a top-tier law firm, I am that city on the hill that cannot be hidden. Facing mountains of discrimination only sharpened my critical thinking, tenacity and sense of justice.

My life’s motto is this: No two people can stand in the same place at the same time. Inevitably, we all will view the world from different angles, perspectives and experiences. We all must learn how to move, shift, inconvenience our traditions and stand in each other’s shoes, if only for a moment. Only then can we truly build an America that the child in me longs for: one nation with liberty and justice for all.

Jervonne Newsome represents major corporations, small businesses and individuals in litigation at Lynn Pinker Hurst & Schwegmann in Dallas. A graduate of the University of Arkansas School of Law, Jervonne is recognized on the list of The Best Lawyers in America for 2021.