Editor’s note: The Texas Lawbook spoke to eight of the 10 Texas Business Court judges and asked them to look back on the first year of operations. This is one of two articles The Lawbook is publishing to coincide with the one-year anniversary of the court. The other article focuses on the experiences of several litigators who have practiced in the Business Court about what’s working well and where there’s room for improvement. Part II can be found here.

Two years ago, lawmakers created a new court, in part as a signal to the business community that Texas is a good place to incorporate and that jurists here could deliver quick, consistent results in complex business disputes.

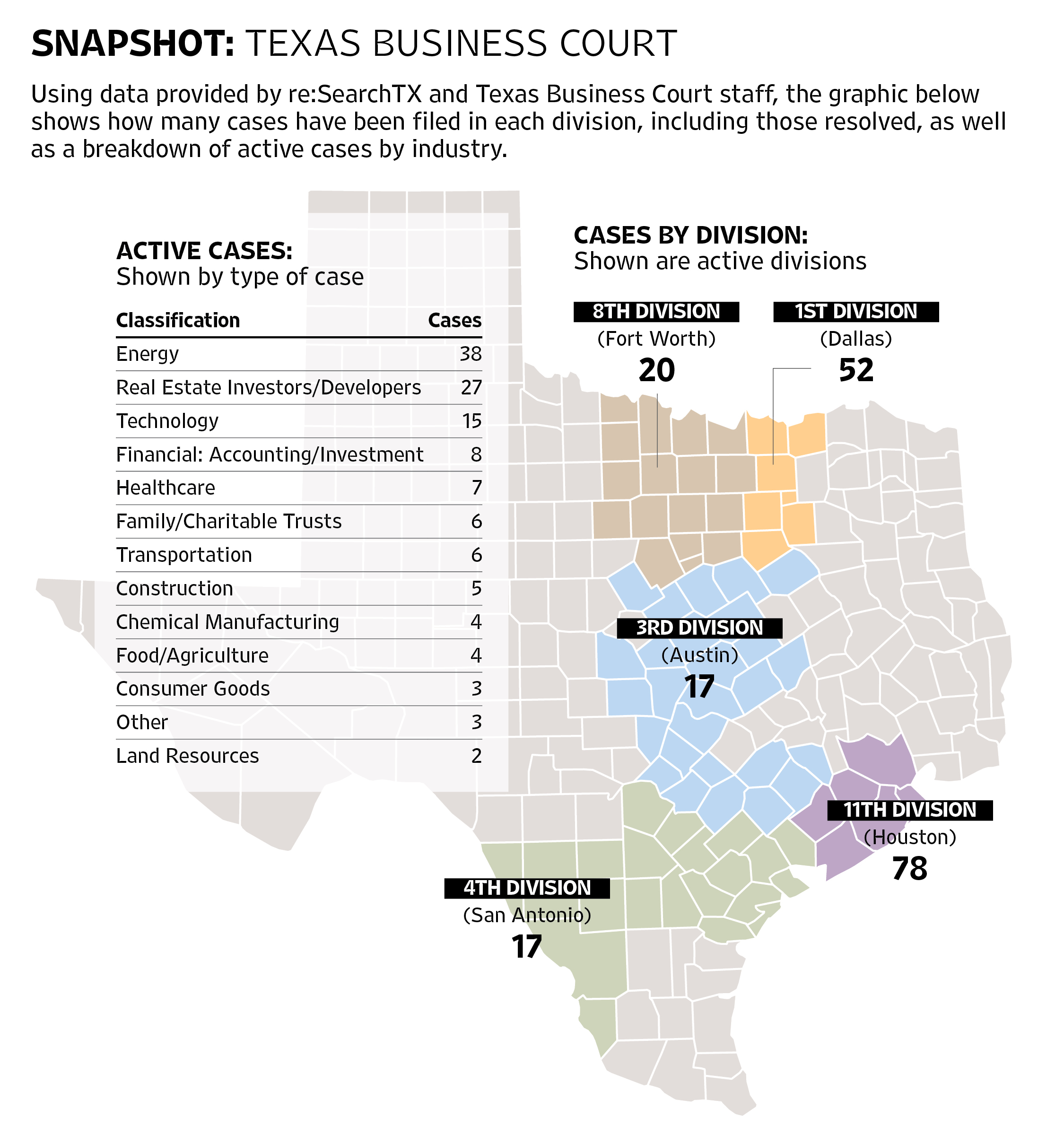

In its first year of operation, the 10 judges appointed to the five divisions of the court have seen more than 180 cases filed. That figure is higher than some of the judges who spoke to The Texas Lawbook expected to see. In recent interviews, the eight judges who spoke to The Lawbook were uniformly optimistic about the court’s future and, in response to questions about what isn’t working or what could be improved, were largely silent aside from discussing some logistical issues with court administration that had to be overcome.

Judge Grant Dorfman, who is based in Houston and also serves as the administrative presiding judge of the Business Court, paraphrased a line from the 1989 movie Field of Dreams — “If you build it, they will come” — in explaining his vision for the court.

“That’s absolutely more than I would have guessed,” Dorfman said. “It’s very reassuring to see the numbers there.”

Data show most of the cases filed in the Business Court have ties to the energy industry, but real estate and construction cases are close behind.

During the legislative process, opponents of the Business Court argued it would take complex business disputes out of the courtrooms in the state’s major metro areas, where Democrats had dominated in 2018 until several lost their seats to Republicans in 2024, and place them into the hands of judges appointed by Republican Gov. Greg Abbott.

Judge Bill Whitehill in Dallas, who said he had never met the governor prior to his appointment, heard the same concerns that the governor was “just going to appoint political hacks that are going to do his bidding.”

But he characterized most of the judges on the court as nonpolitical people and noted that Judge Sofia Adrogué had even run for district court as a Democrat.

“The governor, as I understand it, was very focused on finding highly qualified people to serve on this [court] because this is such a big deal,” he said. “Lawyers, business people around the country, even around the world, are talking about the Texas Business Court.”

Whitehill didn’t apply for the position and thought he would be considered for the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals, which hears Business Court appeals, due to his background as a justice on the Fifth Court of Appeals.

“The opportunity to be on the front end of this historic, important project for Texas was, at this point in my career, too good to not take,” Whitehill said.

Fourth Division Judge Stacy Sharp in San Antonio and Judges Jerry Bullard and Brian Stagner in Fort Worth all applied for the position. Sharp said she was excited about the prospect of having a role that was also “part administrative in conceiving of this creation … that hadn’t existed before.” And Stagner, who said he never ran for an elected judgeship at least in part because he “wanted nothing at all to do” with campaigning and fundraising, happily accepted the appointment.

Judge Patrick Sweeten, who sits in Austin, called it a dual challenge, taking on his first job as a judge on a court that is in its infancy.

These judges weren’t just agreeing to join a court; they were helping create a brand new one and would have a hand not only in establishing case law, but in determining how, and where, the court would operate day-to-day.

Plowing the Way

Fourth Division Judges Marialyn Barnard and Sharp originally had their chambers in temporary office space while their permanent space, located in the One Alamo Center in downtown San Antonio, was being built out.

They played a role in determining the layout of the space and even ordered the microwave and refrigerator. Sharp said the space is still outfitted with temporary furniture that will eventually be replaced with permanent furnishings.

Construction is ongoing on the chamber-adjacent hearing room, where the judges will preside over proceedings that will not include jury trials, but Sharp said having that finished in the second year is the goal.

“A jury trial that we hear could be held in any one of those 22 counties. So for starters, our jury trials would not necessarily be [in] Bexar County,” she said, explaining the plan is to utilize existing county facilities for any jury trial in the Fourth Division’s jurisdiction.

Her first jury trial is currently scheduled for March 2026.

Sharp said she has worked with two counties to secure space for in-person hearings.

“Both have been really helpful and resourceful in getting us courtroom space, courthouse security and all the different things that we’ve needed,” Sharp said.

She has also held quite a few remote hearings via Zoom.

Top row: Judge Brian Stagner, Judge Grant Dorfman and Judge Patrick Sweeten

Middle row: Judge Marialyn Barnard, Judge Andrea Bouressa and Judge Bill Whitehill

Bottom row: Judge Jerry Bullard, Judge Stacy Sharp, Judge Melissa Andrews and Judge Sofia Adrogué

(Photo via Texas Business Court)

The First Division, based in Dallas, has held some hearings at Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law. The division originally was housed in office space at The Shops at Park Lane, but Whitehill said it will soon be moved to SMU’s Expressway Tower.

“I’m very excited to be working with students, having the ability for them to see what we’re doing and participate in that,” Whitehill said. “It’s going to be fantastic for the students.”

The law school is in the process of developing a campus renovation, and part of that will include moving the Business Court into what is now the Carr Collins Hall. Both Whitehill and Judge Andrea Bouressa, who also presides over the First Division in Dallas, earned their law degrees from SMU.

The Eighth Division, based in Fort Worth, has courtroom space at the Texas A&M School of Law.

“The law school has just been fantastic,” Stagner said. They’ve bent over backwards to make us feel at home. And I’ve thought from the very beginning that out of the five different divisions, we easily had the best one in terms of having a home from the very beginning.”

Stagner’s daughter is in her third year at the Texas A&M School of Law, which he said means he gets roped into attending more campus events than he normally would. But increased interaction with the student population is also a goal of Stagner’s. He hopes to do more to alert students about upcoming hearings so they can observe the proceedings.

The Third Division has a dedicated courtroom on the fourth floor of the Heman Marion Sweatt Courthouse in downtown Austin. Its chambers are in the William P. Clements building in Austin, which also houses the Fifteenth Court of Appeals.

The Eleventh Division, based in Houston, has its chambers and courtroom space in the same historic courthouse downtown that is home to the First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeals.

Securing space for chambers and courtroom proceedings was just one of many puzzle pieces that had to be assembled to get the Business Court up and running. Judges also had to get to work hiring staff attorneys, court reporters and a clerk.

Dorfman said despite his experience being twice appointed to a district court bench, developing a new court was a completely different challenge.

“I had a courthouse, I had parking, I had an office, I had staff ready to go, order in the room. All I had to do is buy a robe, put it on and not trip on it on my way up to the bench, and I was fine,” Dorfman said. “In this case, [there was] none of that.”

He started interviewing people a month before the court was set to open via Zoom from his house.

“We’re starting from scratch as a startup court, basically, and that’s presented its challenges. Those have worked out better than I could have dreamed,” Dorfman said. “All the nightmare potential scenarios haven’t occurred yet.”

Houston Sees Surge

Case filings have been the heaviest in Houston.

“We’ve gained traction,” Dorfman said. “I think there was a wait and see period at the beginning in Houston.”

Just four cases were filed across all divisions the first week the Business Court was in operation, but by the six-month mark, more than 80 cases had been filed.

“I think there’s definitely momentum we’re perceiving in the last six months or so,” Dorfman said.

This last legislative session, lawmakers attempted and failed to add a third judge in Houston. But Dorfman, who was a district court judge in Houston for a decade, said he and Adrogué can handle the caseload without adding another judge to the division.

Docket equalization — the process of sending some cases from the busiest courts to courts with less case volume — has been utilized to help alleviate the congestion. So far, only cases from Houston have been transferred to the other Business Court judges.

The Fort Worth judges, who each have two to three Houston cases, said they will travel the 262 miles for hearings and trials rather than making counsel and litigants come to them.

Both Austin-based judges currently have their first jury trials scheduled for November in Houston.

‘Go the Distance’

While the first year had judges dealing with lingering logistical issues and getting comfortable developing case law, those who spoke to The Lawbook said in year two they expect operations to ramp up.

In June, Whitehill entered the contested final judgment disposing of a dispute between Primexx Energy Corp. and minority investors in the company, and the first jury trial for the Business Court will happen this year.

Adrogué and Dorfman have trials on the merits scheduled for Oct. 27.

The case before Dorfman is a $36 million breach of contract lawsuit over purchase of a medical office building in Tomball with alleged plumbing and sewage problems. The case was filed on Sept. 3, 2024, just days after the court’s opening.

The case before Adrogué is a breach of contract suit where damages between $30 million and $200 million are being sought and one party claims he is entitled to a 20 percent ownership interest in a state-of-the-art petroleum export terminal project.

Sweeten has a jury trial scheduled for Nov. 10 in a case that was transferred from Houston. In that case, Antero Resources Corporation is seeking $10 million in damages for an alleged breach of a gas gathering agreement.

The Business Court is unique in that the judges write opinions, whereas district court judges in Texas typically don’t. Whitehill wrote the first opinion for the court in October of last year addressing the removal of cases that were filed before Sept. 1, 2024, and was complimentary of his colleagues’ opinions, too.

“This is exactly what we want, particularly the substantive type opinions,” Whitehill said. “I think trial courts around the state and even some of the intermediate appellate courts are going to be looking at what we’re saying on the Business Organization Code issues, for example, for guidance in their cases.”

Sharp, who has a background is in legal writing and has taught advanced writing for litigation at the University of Texas School of Law, said getting to write opinions for the court “is a really exciting opportunity.”

Not only are these judges writing opinions, but they are also creating a new body of law and precedent for the court. Sharp said that they are all conscientious about that responsibility and get together to brainstorm.

“We’re able to brainstorm together, confer on how to approach new issues — logistical, legal, anything that arises — and it’s that part itself [that] has been such a gratifying experience,” she said.

“It creates these opportunities for creative thinking and being proactive, thinking about what kind of new system could be put in place. How can we build something that endures? It’s a really incredible opportunity.”

Stagner said a goal of his in the second year is to be quicker at writing opinions.

“I like to think that after almost 30 years of practice, I was pretty good and pretty efficient and quick at writing legal briefs,” Stagner said. It’s a whole different mindset to sit down and write an opinion where you’re not advocating, you’re calling balls and strikes and you’re trying to decide who wins based on their advocacy pieces, and put it all together with a nice, cogent theme to it.”

This most recent legislative session brought changes to the Business Court’s jurisdiction. The minimum amount in controversy for Business Court jurisdiction was lowered from $10 million to $5 million, and if both parties agree, a case can now be transferred to the Business Court even if it was filed prior to Sept. 1, 2024.

Dorfman said one of the legislative changes he hopes to see in the future is the funding for the other divisions that would cover the whole state. Currently, only five divisions are funded and staffed — those covering the metro areas of Dallas, Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio and Houston.

“I would like to see us become a statewide institution, with the other six judicial regions having at least one judge, which is what the legislation provides for,” Dorfman said.

Dorfman explained that he had to send a case back to Loving County in West Texas because the Business Court doesn’t have jurisdiction in that area.

Whitehill said he would like the Legislature to address their two-year term limits with a constitutional amendment that would extend them to six years. The governor is only able to appoint a judge to a two-year term by statute.

“I would like to have seen longer terms so that the lawyers and the parties will feel more comfortable coming to Business Court,” Whitehill said.

The complexity of the business disputes filed with the fledgling court has kept its judges busy, something unlikely to change in its second year of operations. Dorfman said he’s fielded questions from colleagues about whether he’s glad not to be presiding over more run-of-the-mill cases.

“I’m like, check with me in a year, I may be dying to try a two-day car wreck at that point,” he said.