A tall, folksy man in a stovepipe hat rides into town on a mule, looking to get his law practice off the ground. He quickly ingratiates himself to the community, making fast friends and even judging a pie contest at the county fair (where he also wins a rail-splitting contest, naturally). Like a good lawyer, or perhaps just a hungry lawyer, he weighs his pie duties carefully, going back and forth between the peach and the apple, steadily gobbling down both. He’s a man of the people, and soon he’ll become a rather impromptu defense attorney in a murder trial.

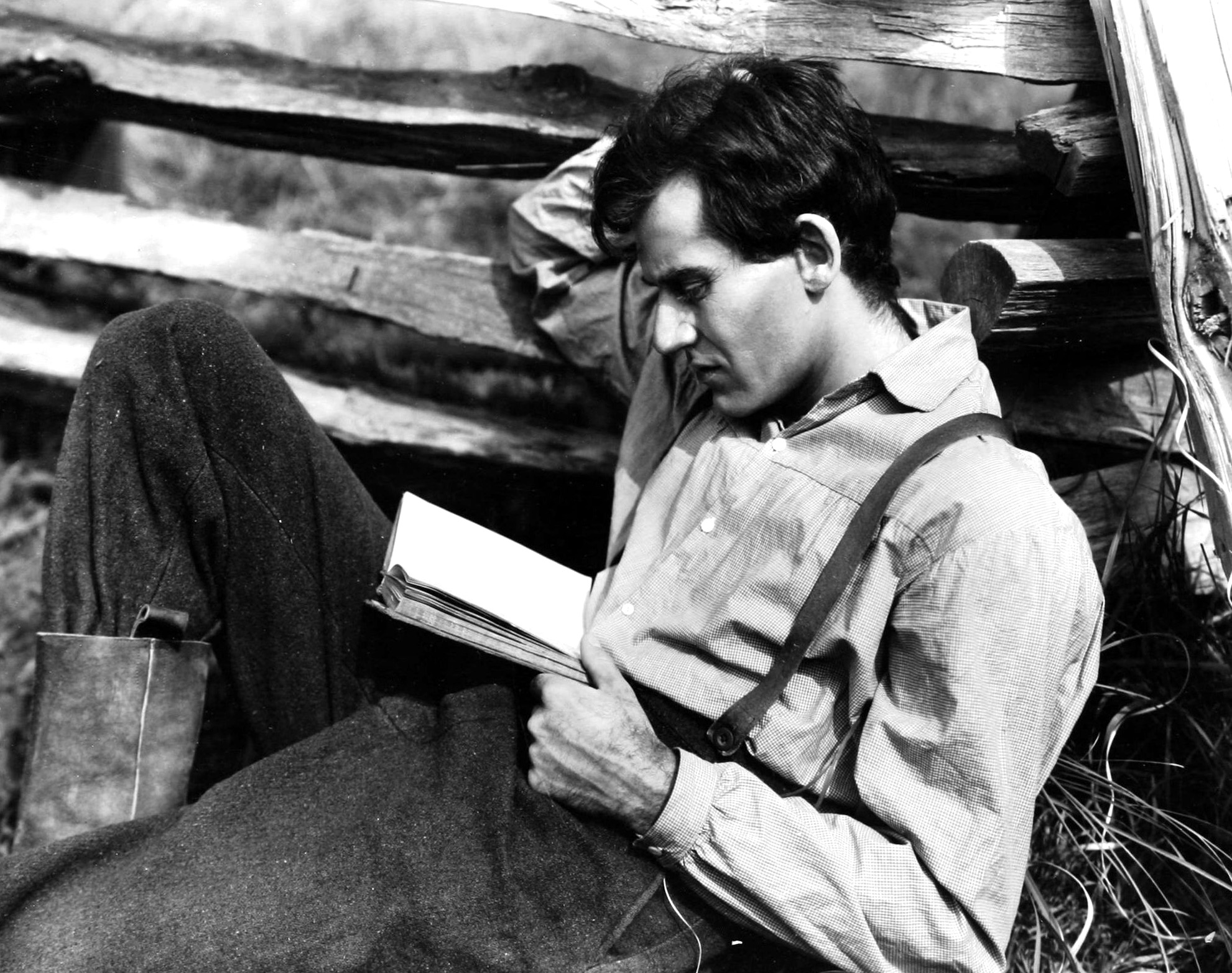

Much of the appeal of The Young Mr. Lincoln lies in the fact that this green lawyer will one day become perhaps the greatest of all U.S. presidents. But that’s still a ways in the future. Set in the 1830s, John Ford’s film is a fictionalized portrait of the Great Emancipator as a young lawyer, beginning to spread his wings in Springfield, Illinois, courting a headstrong young woman named Mary Todd (Marjorie Weaver) and laying on the Everyman vibe as only Henry Fonda could — even with a prosthetic nose.

We see him in action shortly after he arrives in Springfield, settling a financial dispute between two ornery cusses with just enough wiggle room to pocket a small fee. Soon he has a more urgent case on his hands. Two brothers, Matt and Adam Clay (Richard Cromwell and Eddie Quillan), get into a brawl with a local bully who goes by the great bully name of Skrub White. Skrub pulls a gun, but it’s him who ends up shot dead. Honest Abe goes into stoic hero mode, calmly convincing a lynch mob to let the brothers have their day in court where he will defend them.

Ford was on quite a heater in 1939 and 1940, directing Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Guns Along the Mohawk and The Grapes of Wrath. (Shortly thereafter he went off to World War II). When it came to cornpone poetry, capturing the spirit of populism onscreen, he was every bit the equal of his fellow Hollywood titan and World War II veteran, Frank Capra. Indeed, the central trial scene in Young Mr. Lincoln plays like something out of a Capra movie, a public gathering full of eccentric characters (including the judge, jury and prosecutor) and boisterous laughter that belies the fact that two men’s lives are at stake.

The last 40 minutes or so unfold in the courtroom, which becomes a site of aphoristic humor, informal back and forth between the prosecutor (Ford regular Donald Meek) and Lincoln and the quickest, funniest jury selection you’ll ever see. But even this process has a point. Lincoln asks one potential juror, a drunk, burly man in a coonskin cap, if he likes to cuss. The man nods. Does he like to see hangings? The man nods again. Does he tell lies? Again, the nod. Well, Lincoln reasons, if he admits to telling lies, he must be an honest man and therefore fit for jury duty. Here we see the “Honest Abe” mythos in full effect.

At times Lincoln sits in a courtroom rocking chair, propping his feet up on a table, looking as cool as James Dean. In questioning one witness he weaves a tale about a man who stabbed a farmer’s dog with a pitchfork; the courtroom, judge included, erupts into laughter. A man in the gallery shouts out: “Abe, tell ’em the one about the mule!” This is mere moments after that judge, snoring loudly, was awakened by a similar gale of merriment. Ford, an unabashed purveyor of Americana, is in his element here. The courtroom becomes a single, raucous organism, a town square as much as a cradle of justice. Screenwriter Lamar Trotti, himself a nostalgic chronicler of small-town America, makes for a perfect match.

But this Lincoln is also shrewd and tactical, and when he gets an unfriendly witness on the stand (another Ford stalwart, Ward Bond), he takes his time poking holes in the prosecution’s case before going in for the kill. The movie suggests that Lincoln, the young lawyer, will carry critical qualities into his role on the country’s biggest stage in another 25 years or so.

He’s approachable, but not to be underestimated. He’s folksy, but he’s also whip-smart. He’s meticulous, and he’s guided by a steady moral compass. He has no use for a rush to judgment. He’s a strong, fair lawyer. And he might just make a good president someday.