Tumultuous. That’s how municipal bond attorneys describe 2020.

COVID-19 forced bond markets to essentially close in the spring, only to come roaring back. Faced with the continued uncertainty, attorneys pivoted. They helped clients keep the market informed and developed creative solutions to address challenges – all while working mostly from home.

The result: 2020 was a record-breaking year for bond issues in Texas both in number of issues and in their aggregate par value.

Public finance lawyers worked on the more than $66 billion in bond issuances in Texas as of December 16, according the Municipal Advisory Council of Texas.

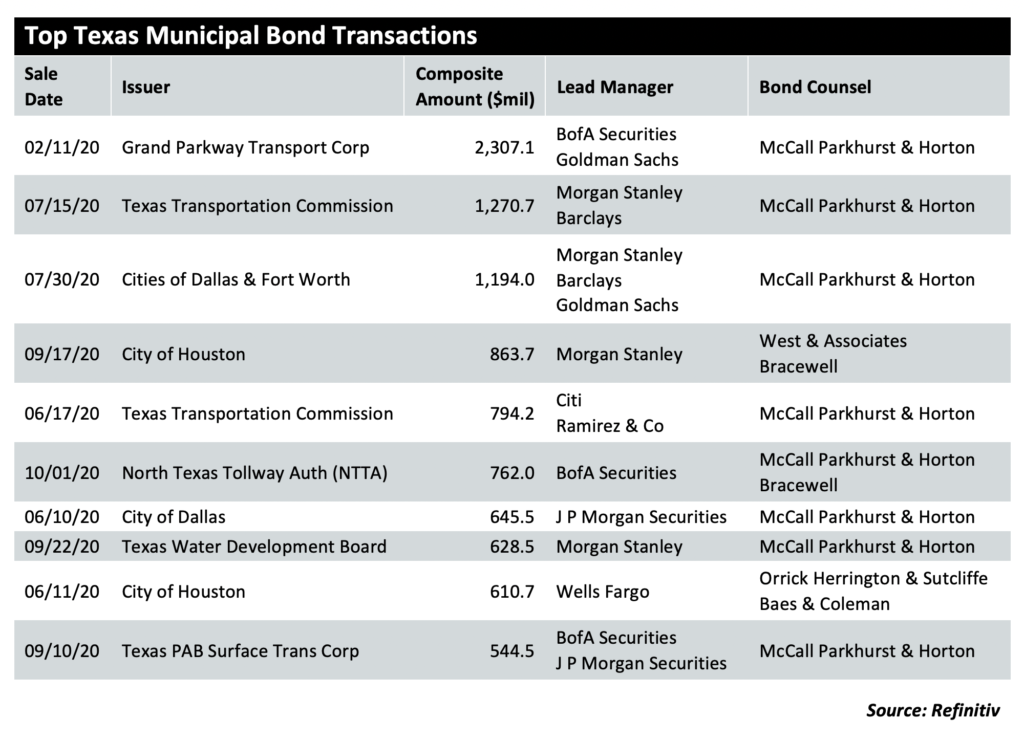

That is $10 billion more than the next highest year, which was 2016 when a par amount of $54.85 billion was issued. While, the largest issue of the year was sold before the pandemic, the next nine largest transactions took place in June or later, according to data provided by Refinitiv. This included a $1.27 billion issue from the Texas Transportation Commission, and a $1.19 billion issue from the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth, both sold in July.

Muni-bond lawyers say the obstacles in achieving such a record were many.

The initial challenge attorneys faced was the sheer number of unknowns due to the pandemic. The economy shut down in April, and no one knew when people would start going back to work.

Law firms had to work through their own logistics issues. Initially, no one was in the office.

“We tend to work in teams,” said Adrian Patterson, public finance partner and Houston office leader at Orrick. “A lot of bonds we issue are tax exempt, so at the very least you have a tax attorney and an associate working alongside you.”

And while some clients went to remote closings, some clients still wanted live closings, Patterson said.

Unlike other states, the Texas attorney general issues an opinion on most debt that is issued locally, and physical documents are typical overnighted to Austin. With all parties working from home, questions on how to get everything signed and overnighted arose, Patterson said.

“We work traditionally in this way, but when you talk to some of our colleagues around the country, it could be modernized, Patterson said. “[The pandemic] it really accelerated that,” Patterson said. “We’ve advanced from the remote working standpoint with the AG office, 10 years in the last five months.”

Updates include wiring money to the AG’s office for transcript fee instead of overnighting checks.

“You couldn’t have operated like this 20 years ago,” said Mark Malveaux, partner at McCall, Parkhurst and Horton, whose clients include the Dallas Area Rapid Transit and Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. “When I first started working, you’d be making photocopies all night.”

Malveaux was impressed by how quickly everyone was able to pivot and how efficient work has been despite everyone working from home. Still, you’re not in front of people.

“You want to see your clients, face-to-face,” Malveaux said. “There’s value in that.”

Another hurdle was making sure the offering documents had adequate information, said Stephanie Leibe, a partner at Norton Rose Fulbright.

Typically, most of the financial information contained in offering documents is based on issuer’s most recent audit. Looking back at historical financial information may not provide a true and accurate picture of the current state of an issuer’s finances, Leibe said.

Bond counsel had to assist issuers as they determined what were reasonable expectations related to the pandemic to ensure that issuers were providing adequate disclosure.

Voluntary Disclosures

Issuers also had to decide whether or not to make voluntary filings.

When his issuer clients started getting calls from institutional investors, Patterson — whose clients include large, urban issuers such as the City of Houston Public Works, Harris County Toll Road, Harris County Metro, and Houston First and the city’s convention and entertainment department — advised his clients to make voluntary filings.

It was a way for them to speak to the market as a whole instead of answering individual calls.

“Really, that’s an indication,” Patterson said. “Because not everyone who has questions calls. For every call a finance department gets from an investor, there other investors that aren’t calling that have the same questions.”

Issuers of debt in the transportation and transit sector were among the most directly impacted by the pandemic because many of them depend on revenue from sales tax. The impact to airports and airlines were particularly significant.

When the pandemic hit, Bracewell was already involved in a transaction representing the Houston airports that had started pre-pandemic.

“In April, we prepared voluntary filings to let the market know how the airport was doing and that proceeded the actual transaction in September; but it was important to get that information flow out to the market,” said Barron Wallace, partner at Bracewell.

In September, Bracewell completed restructurings of debt for both Houston airports and United Airlines. The package included three transactions totaling more than $1.363 billion.

Liquidity Concerns

Many of the large issuers depend on revenues to pay back debt, so there was an immediate concern about the length of time people would be required to work from home. Before federal programs kicked in, and CARES Act dollars began to flow, municipal bond attorneys would have to work with clients to find creative solutions.

In the case of Houston Metro, which earns about 85 percent of its revenue from sales tax, the uncertainty over revenue sparked concern in the transit authority’s commercial paper program – a term referring to short term debt.

“So immediately, they’re thinking about what this going to do to their revenue going forward,” Patterson said. “Nobody is spending, and nobody is traveling. The markets kind of eased up because investors everywhere are thinking about that.”

As credit spreads started to widen, which indicates increased risk, issuers became alarmed at the increasing interest rates they’d have to pay for short term borrowing, Patterson said. They needed more liquidity in the market.

Houston Metro, along with other transit authorities, took a novel approach and bought each other’s short-term debt, Patterson said. It had been previously done in limited instances but became common practice.

Patterson and other public finance attorneys representing transit agencies talked with each other to make sure the investment policies that the transit boards had adopted permitted them to buy each other’s paper, Patterson said.

“Folks said: ‘Okay, when does yours mature?’ ” Patterson said. “Okay, we’ll buy that $10 million. Syndicates formed to be helpful to each other, and that became a preferable alternative to even the kind of Fed liquidity that was coming into the market.”

But the pandemic didn’t impact all issuers and their respective outstanding bonds the same. Property tax obligations, including those issued by school districts, have not been impacted in the same way.

School district funding comes from property taxes and the state, through funding from the Texas Education Agency. The TEA announced that it would use last year’s daily attendance record, for the first semester for its funding formula. To date, that’s helped stabilize a lot of funding for the school districts in the state, which has been helpful, Leibe said.

Shuffling

For some issuers, plans had to be remade. Most of Malveaux’s larger clients had already planned out the entire year in terms of the rollout of transactions. When the pandemic hit, they had to assess what was happening in both the taxable bond market as well as the tax exempt market.

“One client in particular was scheduled to do a taxable bond early on, and then some tax exempt refundings,” Malveaux said. “We really had to reschedule deals, we delayed deals, and changed the order in which we did deals.”

For some clients, it was easier to do tax exempt issues than it was to go into the taxable market, Malveaux said.

“But at the end of the day, everything we wanted to get done, did get done,” Malveaux said.

Record Issues

Issuers also had to think about debt that was going to mature, both this year and in future years. For example, Houston’s Convention and Entertainment Department knows what their debt level service is for the next 10 years, but it doesn’t know what its revenue will be because conventions have been cancelled for the next 18 months, Patterson said.

Looking at revenues to date, issuers had to decide whether to restructure debt in order to reduce principal payments for the next couple of years to help weather through the pandemic, or they may decide to issue debt to have working capital.

“We saw both,” Patterson said.

In addition to restructurings, once the markets opened up, low interest rates created savings opportunity for issuers, Malveaux said.

“Not only refinancings with tax exempt bonds, but rates were so low, you could issue a lot of taxable refundings as well,” Malveaux said.

The unusualness of this year, as it related to municipal bond work, can only be compared to two other events- the terrorist attacks of September 11, when the markets closed and the Great Recession in 2009 when AAA related bond insurers went belly-up, Malveaux said.

“It was amazing to have the market basically close and come roaring back,” Malveaux said. “I don’t see this ever be replicated, and I hope it isn’t.”