Publisher’s note: The Texas Lawbook is pleased to offer this column in partnership with Texas-based Half Price Books sharing our readers’ favorite reads. “My Five Favorite Books” will publish every other Wednesday. Please email brooks.igo@texaslawbook.net for more information.

I have more than five favorite books. This list represents a smattering of what I have enjoyed most across different genres.

1) Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War (400 B.C.).

The Greek historian Thucydides is generally considered the first scientific historian, and this is the best ancient history book we have. His History begins by claiming that in it “there be inserted in it no fables,” but rather that Thucydides desired “to look into the truth of things done…” Thucydides was an eyewitness to many of the events of the Peloponnesian War, and he claimed to have obtained reliable accounts from others who witnessed what he did not. Thucydides’s improvement of the historical method was not that he was more accurate than other ancient historians, but that he was more interested in the causes of historical events, rather than merely reporting them, and he did not ascribe any of those causes to supernatural intervention. Hence, he is called “the father of scientific history.”

Although he was admired in antiquity, his History was not translated into English until the seventeenth century, and even then, it was not widely read until the 1960s, when the parallels between the Peloponnesian War and the Vietnam War became apparent. Twentieth century readers perceived the History of the Peloponnesian War to be relevant to modern politics because of its causes and its cost. The cost, as reckoned by Thucydides, was not just financial, but political, social, and moral, as well. The causes were similar to those that caused World War I and Vietnam. Like those wars and unlike World War II, the combatants in the Peloponnesian War were drawn into conflict, not by the need to oppose evil or aggression, but by jealousy, mutual fear, and their respective webs of alliances. Click here for more info.

2) Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940).

Deciding between this book and Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises is always tough. They are my favorite English language novels. In Hemingway’s terse prose they illustrate the ambiguities facing modern man, war, sexuality, insecurity, fear, courage. For Whom the Bell Tolls, set during the Spanish Civil War, was Sen. John McCain’s favorite book because from it he learned heroism in the face of tyranny. Like the book’s protagonist, Robert Jordan, McCain fought authoritarianism and believed that “The world is a fine place and worth fighting for and I hate very much to leave it.”

Another reason I love this book is that it is the only great novel I know of that mentions Corpus Christi, Texas, my hometown. Click here for more info.

3) Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian (1985).

If For Whom the Bell Tolls is a primer on heroism, Blood Meridian is the masterwork in describing real evil—not the supernatural kind, the kind that exists in the physical world. You will both thank me and hate me if you read this book. It’s based on a true story, and it’s terrifying, and you won’t be able to put it down. It contains perhaps the most mesmerizing diction of any late twentieth century novel—like Shakespeare or Milton or the Old Testament. Click here for more info.

4) Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos of Nafpaktos, Life After Death (1995, Esther Williams, translator).

In the realm of philosophy and theology, what questions are more important than what is the nature of death, and what happens after it? Translated recently from the original Greek, this book answers those questions from the perspective of an Eastern Christian bishop immersed in patristic theology. Western theology seems to assume that heaven and hell are places created by God to either punish or reward us. Vlachos argues that, based on the teachings of Jesus, his apostles, and their early successors, this is a false construct. An all-merciful and all-loving God would do no such thing. Rather, what limited human understanding calls heaven and hell are not places, they are conditions. When the soul leaves the body, it is freed from time and space and enters the eternal dimension. There we will encounter God face to face, instead of “as through a glass darkly” in this created universe. How the soul experiences that intimacy with God, that transcendent light, can be either paradise or damnation, depending not on God, but on us.

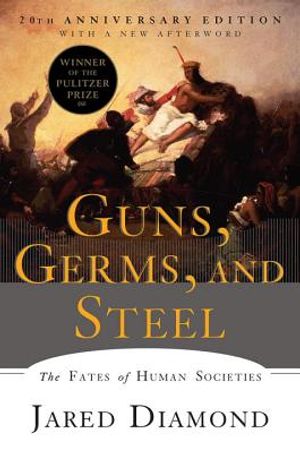

5) Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997).

It seems only fair to include one conventional non-fiction book from the natural sciences. The first book I would read in that genre is this one. In it, Diamond, an anthropologist, explains the big picture of earth’s pre-history. Why are there llamas in South America but not Europe? Why tigers in Asia and bison in North America? Why is rice the staple crop in East Asia, while in the Americas it was corn, and in Europe and the Near East, wheat? Why did agriculture and civilization arise when they did and where they did? These and many other imponderables are explained neatly and scientifically. It’s a mind-blower. Click here for more info.

Dr. Bill Chriss is a historian and past chair of the State Bar’s Appellate and Insurance Sections. He is the author of Six Constitutions Over Texas and The Noble Lawyer. He also publishes a Substack blog on politics, history, literature, and philosophy.