A seismic–and some argue long-overdue–shift is underway in the manner in which Texas law firms make important strategic decisions.

For two centuries, law firm partners across the country decided which lawyers to recruit, hire and fire; which practice groups to expand, shrink or even eliminate; and which clients to represent and how much to charge for legal services.

But since the Great Recession of 2008, law firms have seen dramatic shifts in the demand for legal services. Driven by technology and cost-conscious clients, firms have had to change their approaches to hiring and developing lawyers and serving and billing clients, as well as finding or retaining a more demanding clientele.

Interviews with law firm leaders by The Texas Lawbook show that Texas law firms — long insulated from trends going on in the rest of the country — are no longer immune in this more competitive environment and are increasingly turning over many of these critical decisions to non-lawyer professions.

Over the past five years or so, nearly every major law firm operating in Texas – including Akin Gump, Baker Botts, Bracewell, Haynes and Boone, Norton Rose Fulbright and Vinson & Elkins – has hired non-lawyer professionals to handle key marketing and staff development operations.

Their titles range from chief talent officers, directors of practice management, chief pricing strategists, directors of business development and chief value officers. They are more likely to have MBA’s than JD’s. And their compensation often reaches the mid-six digits.

Their mission is simple: boost revenues and increase profits.

When Baker Botts brought in non-lawyer Gillian Ward as chief marketing officer in 2014, the firm didn’t have a research function. She has since built a robust one. The Houston-based firm also didn’t have a pricing strategist, so it hired John Strange away from V&E. Last fall, the firm even considered hiring a competitive intelligence manager but put those plans on hold when it brought in business development director Clara Rodriguez.

“Clients have plenty of choices and want to know, ‘What’s the value-add to my business?’ So we have to help educate the lawyers as to what that means and help position them to secure the work,” Ward said. “The days of going to lunch and coming back to three messages and new cases sitting on your desk are over.”

Ward said lawyers now get development training from the time they join the firm to the time they make partner. Even client interviews are monitored by Ward and her team.

“It could be for client retention or for growth,” she said. “What we bring back is intelligence: here’s what the program should look like over the next six to 12 months.”

Legal industry experts say that hires like this are part of a decades-old movement to operate corporate law firms more like businesses. Critics claim commoditization of legal services marks the end of law as a noble profession, putting firm revenue ahead of clients.

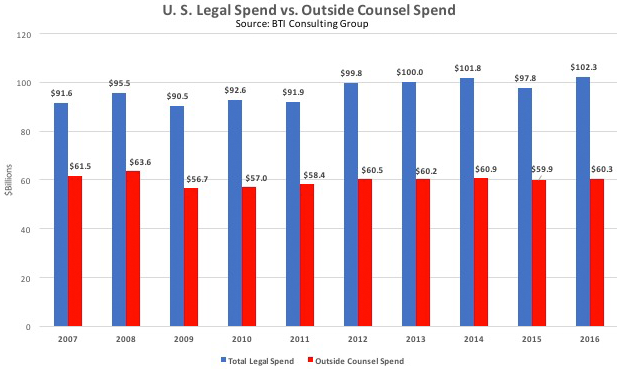

But firms are finding that even their clients are driving change. Competition from non-law firm providers, non-traditional firms driven by technology and in-house legal departments are permanently changing the legal profession into a legal industry. Moreover, there is stiffening competition for outside legal spending, which remains relatively flat.

According to BTI Consulting, spending for legal services in 2012 was $99.8 billion, $60.5 billion of which went to outside counsel. Although a record $102.3 billion was spent on legal services in 2016, outside legal spending fell to $60.3 billion.

A national survey by legal consultants Altman Weil underscored the lingering sense of anxiety. Only 38 percent of law firm leaders said demand for legal services had returned to pre-2008 levels. And most (62 percent) think that erosion is a part of a permanent trend. Nearly 70 percent say they’ve lost business to in-sourcing by corporate legal departments and 85 percent see the replacement of human legal resources by technology as a legitimate threat.

In late October, about 100 non-lawyer law firm leaders from Texas and surrounding states met in Denver for the Legal Marketing Association’s regional conference to discuss their expanding role and influence in the leadership of law firms.

The LMA, which is made up of chief marketing officers and directors of communications and business development, featured programs about “leading change” within law firms, the use of artificial intelligence and a seminar called “Expanding Influence and Increasing Effectiveness Within the Firm and Beyond.”

(Editor’s Note: The Texas Lawbook is a regular sponsor and supporter of LMA regional meetings.)

“We are seeing more influence of non-lawyer experts in deciding how firms should provide legal services,” Debra Baker, managing director of Chicago-based law firm consulting firm GrowthPlay, told the LMA members on Oct. 27.

Baker, a former lawyer, challenged the non-lawyer professionals to be more creative and more aggressive in driving client-related decisions. “We cannot rely on our attorneys to show the courage to provide a new and better way,” she said.

William Cobb, a law firm consultant in Houston, said the trend is the result of law firms feeling pressures from their own partners to increase revenues and profits. “The competition has been increasing at a phenomenal rate and law firms have come way upstream on how to manage cases and price them,” he said.

Cobb says non-lawyer professionals are making Texas law firms more competitive in staff development, research and fee structure and pricing. “Lawyers have figured out they’re not good at those things,” he said.

Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld brought in Aleisha Gravit ten years ago as chief marketing officer. Though based in Dallas, she’s in charge of all marketing and communications for the firm globally as well as business development. In August, she added the firm’s library/research operations to her oversight.

Gravit said her firm is starting to spend more time on competitive intelligence — she has someone on her team dedicated to that function. She’s even sending some of her research analysts to New York to attend an LMA certificate program on the subject.

“The markets are crazy, not just in Texas, but in New York, London and D.C.,” she said. “Without intelligence and knowledge of what’s going on in those markets and what potential clients are doing, I can’t imagine you can effectively manage.”

Toby Brown led pricing at Akin Gump in Houston before he left in May of last year to be the chief practice management officer at Perkins Coie in Seattle. Kristina Lambright, who worked with Brown as Akin’s director of strategic pricing, followed him to Perkins in October of last year, where she is director of pricing and legal project management.

Brown is well-known in the industry, having co-authored “Law Firm Pricing: Strategies, Roles, and Responsibilities” and being one of the creators of “3 Geeks and a Law Blog,” which discusses such issues as convergence, advanced analytics and automation. (The other two “geeks” are Greg Lambert, Jackson Walker’s chief knowledge services officer in Houston, and Sophia Lisa Salazar, Norton Rose Fulbright’s digital senior manager, also in Houston).

Brown said four out of five of the top U.S. law firms have employed pricing specialists for a few years. What’s new, he said, is combining pricing with legal project management. “It’s not just pricing anymore,” he said. “It’s how you engage with your client to provide service in more innovative ways.”

Brown points to Chicago firm Seyfarth Shaw, which has a 60-lawyer office in Houston. The firm is doing full-on legal project management with SeyfarthLean Consulting, which employs the Six Sigma and Lean Six Sigma process improvement methodologies developed by General Electric. The unit is led by labor and employment lawyer Lisa Damon in the firm’s Boston office and managing director Kim Craig in Chicago.

Cobb, the Houston consultant, said Seyfarth Shaw’s innovative efforts are well-known and respected. “The firm has gotten so good at project management, it has its own consulting firm that helps clients do it,” he said.

John Strange was Baker Botts’ first director of pricing and project management, which changed its name to practice management in January. The marching orders were simple: use practice management tools to boost revenue.

Strange said his team gets involved “from the get-go” during the firm’s strategic planning process, when department chairs determine what the priorities are in terms of financial performance and potential client targets and lateral hires. The team creates various goals and pricing scenarios that are taken to the client. If one is approved, the team tracks its performance against the plan and shares alerts with those involved.

If a matter goes off plan, Strange said his team is then responsible for figuring out why and what the firm can learn from it. “When you miss, you take your lumps, but you’re constantly trying to improve the process,” he said.

It wasn’t easy at first. Some attorneys became “heavier customers” of their services, Strange said, while others pushed back.

“There’s always an initial adjustment period,” he said. “But as people had exposure to what my team can contribute, they began to lean on us. They want to know how their matter is performing, how their practice is performing, how they should practice a matter and who should they hire.”

So far, it’s working. In 2014 and again in 2015, revenues increased almost 10 percent and profits increased more than 15 percent per year. His team now has eight members, including a new pricing analyst who joined this past summer. “We’re very heavily integrated into how the firm and departments operate now,” he said.

Strange said the team is now trying to move partners away from the “nuts and bolts” of administration to focus on delivery of legal services, leaving day-to-day operations in the hands of the staff.

When Strange left V&E, the firm’s non-lawyer COO, Tim Armstrong took a different approach: The firm installed directors in each practice area to work on pricing models, which are then approved by a pricing committee. “We had dedicated pricing people, but I’m not sure we saw enough volume to justify it,” V&E CFO Allen Gilbert said.

Gilbert say he spends a lot of his time these days on requests for proposals, or RFP’s, as well as non-standard fee arrangements — which are a lot more cumbersome than most of the firm’s normal rate arrangements because of their tighter guidelines. “We work a lot closer with business development than we did five to 10 years ago,” he said.

The CFO said many of V&E’s clients are either reducing the number of law firms they’re doing business with or doing the work themselves.

“A lot of times they are looking for an expertise, but a lot of times the larger clients are looking to commoditize legal services,” he said. “They’ll whittle it down to a few firms and create a bidding process; and then for high-end work, go outside the panel.”

Gilbert said it can be a lose-lose situation. “Our hope is that when we get on those panels, we’re not doing suicide pricing,” he said. “What we really want is to get a foot in the door.”

On the competitive intelligence front, COO Armstrong said V&E has been transforming its library into more of a knowledge services function that works closely with its marketing people. But he emphasized that most of the firm’s resources are embedded in its practice groups, a structure that allows it to have people with dual functions.

“With all the pressure on the cost side of the equation, it’s hard to have staff who are idle,” he said. “Maybe some of these folks are involved in client intelligence, helping us manage experience databases or are involved in business development investments we’re making around events.”

With this multi-disciplinary approach, “We can ramp up and ramp down and shift resources where we need them,” he said.

Other firms are incorporating corporate intelligence to gain an edge. Bracewell, for instance, has a strategic client intelligence director in Houston, Bob Menefee.

Menefee wouldn’t speak to The Texas Lawbook, but he seems to wear a lot of hats. His LinkedIn profile states that he assesses the profitability of new business prospects and proposals; develops pricing solutions for clients, including alternative fee arrangements; helps prepare responses to RFP’s; coaches attorneys on pricing; and provides strategic intelligence to partners and management to boost client development and growth.

Haynes and Boone, which also declined to talk with the Lawbook for this article, has a dedicated director of business intelligence in Dallas, Emily Cunningham Rushing, who has been working in the area for 10 years. She has a law degree from the University of Houston Law Center, but also holds an MLIS from the University of North Texas in Library and Information Sciences.

Norton Rose Fulbright has Saskia Mehlhorn as its director of knowledge management and library services in Houston. She also holds a law degree from the University of Houston Law Center and like Rushing, an MLIS from UNT.

Several national law firms with a significant Texas presence have a strong reputation for their knowledge management expertise. Kate Cain is director of market intelligence at Chicago’s Sidley Austin, which has more than 100 lawyers in Dallas and Houston; Louise Tsang is manager of business intelligence at Greenberg Traurig, which has offices in Houston, Dallas and Austin; and Cheryl Disch is senior manager of marketing information systems at Philadelphia-based Duane Morris, which has a Houston outpost.

John Eix, regional development manager at Hunton & Williams in Dallas, said his firm has dedicated departments devoted to pricing and competitive intelligence. “Most business development in Texas is relationship-driven, but we’re trying to use technology to drive that,” he said.

While non-lawyers and their skill sets are on the rise in law firms, the perceived need is not universal. Legal research firm Acritas, for instance, found in a recent survey that 82 percent of law firms have some form of competitive intelligence operation but only 8 percent of law firm leaders regard their CI efforts as highly effective. Still, one in three firms plans to expand their CI capabilities within the next year.

“There’s an incredible amount of diversity and it also seems evident that this is a relatively nascent area for law firms,” said Houston law firm consultant Marcie Borgal Shunk, whose company, The Tilt Institute, co-produced the survey with Acritas.

Acritas’ U.S. vice president, Elizabeth Duffy, agrees: “The challenge for law firms is understanding all the data sources that are out there and translating it into insight that can drive decisions.”

Shunk said one of the more interesting uses of competitive intelligence is to make better strategic decisions, such as analyzing an acquisition target, opening a new office or anticipating changes in the markets and communicating them to their clients.

“Instead of waiting for legal work or clients coming to them on problems, clients would like to hear more from their law firms on a proactive basis: What should we be looking for? How will it impact business or create risk or opportunity?” Shunk said. “They are analyzing industry or specific issues, creating a scenario plan and approaching them with competitive advantage opportunities. It’s a much more sophisticated approach.”

—Mark Curriden and Allen Pusey contributed to this report.