Could the swing of Texas’s big courts of appeals to Democratic majorities lead to more removals from state to federal court?

Despite the hurdles federal courts have raised to removal jurisdiction over the years, the addition of five new judges to the Fifth Circuit certainly creates an opening.

Erie theoretically ended the days when parties’ rights depended on whether a case advanced in state or federal court. Yet, generally, plaintiffs today still favor state court, while defendants prefer federal court. For those who (rightly or wrongly) think judges’ political-party affiliation influences their views of substantive law, these forum preferences will likely increase after the November 2018 elections.

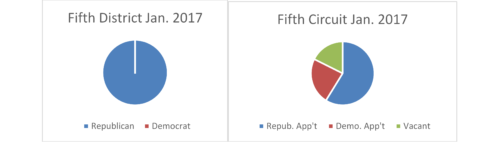

Consider that, heretofore, the courts of appeals in Austin, Dallas, and Houston were dominated by Republican judges. At the same time, the majority of Fifth Circuit judges were appointed by Republican presidents. The Dallas Court of Appeals is a good example:

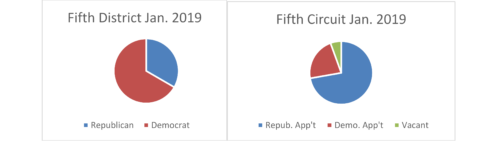

But the Democratic wave in the state courts of appeals, combined with President Trump’s appointment of five new judges to the Fifth Circuit, has created a sharp contrast—at least as to purported party affiliation—between the state and federal forums:

It is easy to imagine that, in this new landscape, fights over forum selection will only grow in number and intensity. Defendants will perceive an even greater risk of unfavorable outcomes from Democratic majorities that might be more sympathetic to plaintiffs.

The lack of prior opinions to mine among the newly-minted Democratic judges will only heighten the uncertainties. Likewise, plaintiffs will view the Fifth Circuit as having shifted more “conservative,” with the addition of President Trump’s appointments.

As these fights make their way through the system, the Fifth Circuit should have ample opportunity to consider just how removal-friendly the federal courts in Texas will be as a matter of law. That Republican presidents appointed most of the Fifth Circuit’s judges, however, does not mean it is necessarily easy to predict where that law will end up.

For example, judges whose “conservatism” manifests itself in restraint, fidelity to (even erroneous) precedent, and a limited reading of the removal statute might require more persuading to open the federal courthouse doors.

On another hand could be judges who think federalism favors a presumption of state-court adjudication where state-created rights are at issue. Other judges, however, might scrutinize whether parties are using procedural shenanigans to evade the Constitution, which confers diversity jurisdiction when diverse parties have a true “case or controversy.”

An illustrative recent case from the Fifth Circuit is Ashford v. Aeroframe Services, Nos. 17-30142 & 17-30483 (Oct. 26, 2018). A Louisiana citizen sued two defendants under Louisiana law, one of whom was also a Louisiana citizen. The out-of-state defendant removed the case, citing an email obtained through discovery. In the email, the plaintiff’s counsel stated that the non-diverse defendant was cooperating with plaintiff’s counsel and would stipulate to paying what was owed to plaintiff and other former employees of the non-diverse defendant. The federal district judge accepted the case.

On appeal, the case produced three opinions from the Fifth Circuit panel:

• Judge Higginson, a President Obama appointee, wrote a short opinion ordering remand, based on “hornbook law” that diversity jurisdiction “depends upon the state of things at the time of the action brought.” Although 28 U.S.C. § 1446(b)(3) says that a case may “become removable” even “if the case stated by the initial pleading is not removable,” Judge Higginson declined to construe that provision beyond circumstances already recognized by precedent, e.g., when a plaintiff amends the complaint to add a federal claim.

• Judge Davis, a senior-status appointee of President Reagan, concurred because he thought the email was insufficient evidence that the plaintiff and non-diverse defendant were aligned in their interests. Judge Davis also thought that fidelity to Fifth Circuit precedent required the court to look at the “principal purpose of the suit” to decide whether the plaintiff and non-diverse defendant were adverse enough to defeat diversity jurisdiction. In this case, he thought the test favored remand.

• Judge Jones, also an appointee of President Reagan, dissented because the majority “refuse[d] to realign the parties according to their true and ultimate interests in the litigation.” In her view, Supreme Court precedent requires courts to “look beyond the pleadings, and arrange the parties according to their sides in the dispute” to analyze the existence of diversity jurisdiction. Underlying Judge Jones’s opinion was her apparent concern about the case having “more than a whiff of professional impropriety and shenanigans.”

How will the new appointees of President Trump approach this issue?

The opinions and en banc votes of Judges Ho and Willett show an enthusiasm for “big ideas” about the structure of government, suggesting an opening for Judge Jones’s less formalistic approach to removal. It is yet to be seen what principles will most motivate Judges Duncan, Engelhardt, and Oldham.

But it seems clear, at least, that lawyers for either side should get ready to make their case.

David Coale is a partner at Lynn Pinker Cox & Hurst, where he specializes in appellate law. Paulette Miniter is an associate at the firm and also focuses on litigation and appellate work.