Charles Holland Duell became famous for something that never occurred. As folklore goes, during his tenure as United States Commissioner of Patents (prior to his becoming a judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals), Duell purportedly said, “Everything that can be invented has been invented.” However, this attribution has been fully debunked by later scholars and commentators. Indeed, Duell’s true perspective is embodied by his statement in 1902 as follows: “In my opinion, all previous advances in the various lines of invention will appear totally insignificant when compared with those which the present century will witness. I almost wish that I might live my life over again to see the wonders which are at the threshold.”

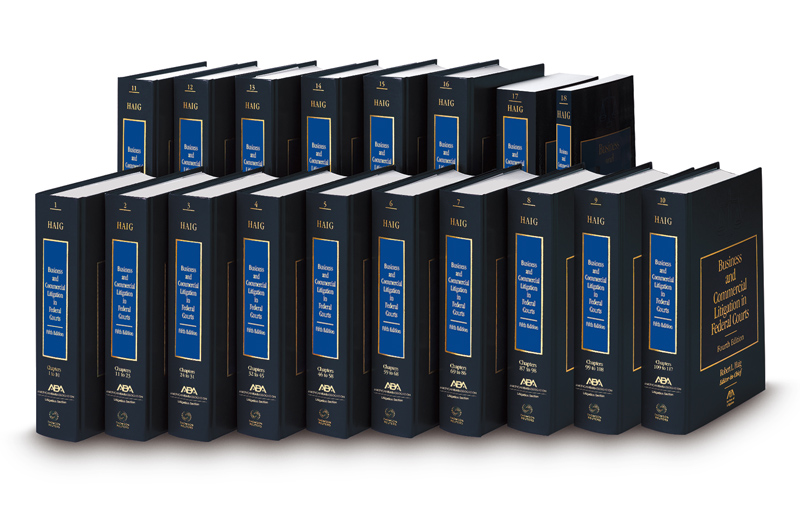

These two discordant themes, the first folklore and the other a prescient prediction of the following 120 years, to some degree describe my disparate thoughts when four years ago I reviewed the 14-volume fourth edition of Business and Commercial Litigation in Federal Courts and my current review of the new 16-volume (plus supplements) fifth edition published in December.

I wrote four years ago that the fourth edition was aptly described by reviewers as breathtaking in its scope and breadth and noted the treatise “preempts the field” and “covers virtually every imaginable topic and more than a few topics that most practitioners would not imagine would be addressed in a substantive or procedural federal court practice treatise.” Essentially, like the fictional quote from Charles Duell, I internally concluded there was likely a paucity of new subjects to cover and that future iterations of the treatise would primarily involve only case law, statutory or other typical “updates” to the substantive and procedural chapters and topics.

Like the fictional comment of Duell, I was mistaken. The fifth edition has 26 entirely new chapters on new topics. A few of these new chapters (such as Fraudulent Transfer, Fee Arrangements, and Litigation Management by Judges) are not all that surprising and may not have been included in earlier editions simply because of the time constraints and the logistics of getting such a significant work out the door and published – the simple fact that at some point the editor and publisher have to “pull the trigger” and the recognition that “perfection is the enemy” of both done and great. Other new subjects in the fifth edition were simply on no one’s radar screen four years ago. If they were thought about at all in the context of a typical sophisticated commercial litigation practice, they were secondary or even tertiary matters.

The new chapters include the following: Animal Law; Art Law; Artificial Intelligence; Budgeting and Controlling Costs; Climate Change; Comparison with Business and Commercial Litigation in Delaware Courts; Comparison with Business and Commercial Litigation in New York Courts; Comparison with Business and Commercial Litigation in Canada; Comparison with Business and Commercial Litigation in Mexico; Congressional Investigations; Constitutional Litigation; Coordinating Counsel; Corporate Litigation Reporting Obligations; Corporate Sustainability and ESG; Fee Arrangements; Fraudulent Transfer; Litigation Management by Judges; Monitorships; Political Law; Shareholder Activism; Space Law; Third-Party Litigation Funding; Trade Associations; Use of Jury Consultants; Valuation of a Business; and Virtual Currencies.

I still do not fully understand artificial intelligence, virtual currencies, blockchain technology, and non-fungible tokens on any but the most rudimental level but can readily see how important they are becoming. These matters will be the subjects of the highest stakes litigation in the years to come, much like the technology at the epicenter of business and commercial litigation now was nearly unknown to most lawyers 25 years ago. For instance, social media, ubiquitous internet applications on computers and mobile devices, search engines, cloud based backup and later cloud-based storage and virtual servers, software as a service, cybersecurity and the like are now commonplace technology matters, a routine part of our everyday lives and the stuff of significant business and litigation by (or against) their creators and others such as hardware and software consultants, providers, software and hosting platforms, implementors, custom coders and other technology “players.” Disputes involving these technologies lead to claims of many millions of dollars for alleged patent violations, trade secret matters, vaporware, data security breaches, other failures to deliver, employment matters involving executives at the highest levels, class actions and every imaginable iteration of disputes as the technology evolves, morphs and inserts itself into the core fabric of our business and personal lives at an ever-increasing pace. I expect AI and virtual currencies, already the subjects of some litigation, will become an even bigger part of the next wave of tech litigation. Another example: Given the public and private funding of rockets, spacecraft and satellites, space law will likely be fertile grounds for future litigation – think “law of the sea” as the age of exploration dawned. You can decide after reading the Space Law chapter whether to pitch Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk or NASA for the inevitable litigation that will surely ensue in this space (a little pun).

While I have not read these chapters in full, I have parsed them sufficiently to be comfortable that if I read them in detail before an initial meeting, I would have enough knowledge to speak intelligently with knowledgeable folks about the likely issues they will face in a potential or already filed litigation without looking like I was a total novice in the area.

Similarly, the four new chapters comparing business and commercial litigation in Delaware, New York, Mexico and Canada will be incredibly useful as the world continues to “shrink” even faster than it has the last 50 years and as businesses have a choice of where to pursue redress for their business and commercial disputes or are involuntarily dragged into a venue not of their own choosing.

For litigation involving only domestic parties and disputes, being able to give the client a sense of what the litigation will look like if filed in the state courts of the two predominant business litigation venues – Delaware and New York – is critical. Business and commercial litigation in the state courts in New York and Delaware is somewhat different from much of the rest of the country. Jurisdiction and venue often are available in Delaware because many business entities are incorporated or operate in that state and because Delaware has long had a reputation for very sophisticated business courts. New York remains the financial epicenter of the United States and has become highly competitive as a choice of forum for business litigation because of the creation and reputation of the Commercial Division of the New York Supreme Court (the general jurisdiction trial level court in New York) some 27 years ago in 1995. Much like the Delaware courts, the New York’s Commercial Division provides significant comfort to the litigants that a judge with the skill sets and experience in sophisticated business litigation will be guiding the process and making the substantive legal decisions in the case. The chapters on business litigation in those two states provide much information in a concise form about litigation process and dynamics in each of those venues and how state court litigation will differ from that filed in federal court.

On a side note, Bob Haig, the editor-in-chief of the treatise, is the chair of the Commercial Division Advisory Council established by New York’s chief judge to advise on an ongoing basis about all matters involving and surrounding the Commercial Division. Bob Haig has also been instrumental in introducing the concept of specialized business courts in approximately 20 additional states. I expect the larger states that adopt this structure may well warrant their own chapter in the sixth edition of the treatise.

The new chapters in the fifth edition continue to provide deep guidance in subjects that do not fall nicely into either “procedural” or “substantive law” categories but are of immense practical importance in successfully conducting and managing business and commercial litigation in the federal courts, including: Coordinating Counsel; Corporate Litigation Reporting Obligations; Fee Arrangements; Litigation Management by Judges; Third-Party Litigation Funding; and Use of Jury Consultants.

There are significant embedded resources in the treatise to make it efficient and easy to use. First, is the seven-page Summary of Contents which simply lists all of the chapters with the procedural stuff of litigation arranged to a large degree as a litigation would typically unfold – from inception (or earlier) through a final appeal. The more substantive legal topics or other litigation-related matters are thereafter set forth in logically related groups, although some chapters are by their nature somewhat a stand-alone topic – for instance Animal Law. The Summary of Contents will be your first stop.

Once you have identified a promising chapter, your next stop will be the detailed Table of Contents, which gives a very detailed description of what is contained in each chapter (about 2-3 pages for each chapter) and should let you determine immediately if the chapter may be of use. It is then on to the chapter itself or, if it does not look to have what you need, your next move is to the 278-page Index in a stand-alone softbound supplement to the treatise. To say that the Index is very complete and cross-referenced would be a significant understatement. It will generate ideas if your first two steps don’t do the trick. I expect the Index may have been done using the AI referenced above because it seems beyond the capacity of a human to generate in a single lifetime. There is also included with the treatise a separate volume of Table of Cases (over 2,000 pages) with citations and cross-references to all of the cases referenced in the treatise.

The treatise remains available in hard copy and electronically through Westlaw access. There are some advantages to using the treatise on Westlaw. Obviously, the Westlaw version is quite portable and a laptop with Westlaw access travels a bit more easily than the 18 volumes of the hard copy. Additionally, the Westlaw version has hyperlinks to the internal cross-references in the treatise and will take you to an entirely different volume of the Treatise with the click of a keyboard or mouse. The Westlaw version also has hyperlinks to other cited resources outside of the treatise, including the full version of every case and statute cited as well as links to many of the scholarly works and third-party resources referenced by the authors. As noted in my prior review, I remain somewhat partial to the hard copy for its classic look and feel. The 16 main volumes are hardcover, occupy about three feet of shelf space, have navy blue with gold lettering and include two additional softbound volumes for the Index and Table of Cases. The 16 volumes look good enough on a bookshelf that they easily passed the spousal display approval standard. The obvious solution – to acquire the hardcopy and have access to the Westlaw version – may require a further spousal consultation. All royalties for the treatise go to the ABA Section of Litigation.

I remain particularly pleased that so many of the treatise’s authors are my fellow Texas lawyers and Texas judges – many of whom I have worked with over the years. They are among the first rank of Texas-based litigators and judges with national and sophisticated practices and dockets. These authors include Chief Judge Barbara M. G. Lynn of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas, United States District Judges George C. Hanks Jr. and David Hittner of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas; and the following well-known Texas lawyers: Harry M. Reasoner, George M. Kryder, and Jordan W. Leu of Vinson & Elkins; Rod Phelan and Jessica Bateman Pulliam of Baker Botts; Van H. Beckwith of Halliburton Corporation; Melanie B. Rother, Layne E. Kruse, Edward C. Lewis, and Matthew A. Dekovich of Norton Rose Fulbright; David J. Beck of Beck Redden; Mary-Olga Lovett of Greenberg Traurig; Barry Barnett of Susman Godfrey; William N. Warren of Kelly Hart & Hallman; Vincent J. Hess of Locke Lord; Charles L. Babcock of Jackson Walker; David S. Coale of Lynn Pinker Hurst & Schwegmann; Thomas R. Ajamie of Ajamie; Vincent E. Morgan of Bracewell; Eric J. R. Nichols of Butler Snow; and Timothy S. Durst of O’Melveny & Myers.

Chris Nolland has decades of experience in the fields of negotiation and mediation. He regularly serves as a neutral mediator and arbitrator and as settlement counsel.