The Securities and Exchange Commission closed fiscal year 2023 on Sept. 30 with a flurry of enforcement filings. A few things stand out.

Chief among these is the sharp increase in cryptocurrency and other digital asset enforcement actions, which far outstrips the agency’s activity in this space in earlier years. There was also a pronounced jump in enforcement focus on corporate internal controls, continuing a trend that started last fiscal year. Meanwhile, the SEC paid record whistleblower awards and stepped up its whistleblower protection efforts, highlighting their importance to the SEC’s enforcement program. On the other hand, ESG enforcement activity appeared to wane, which contrasts with the prominence SEC officials have given to ESG issues in speeches and proposed rulemaking. And SEC administrative proceedings suffered more blows in court challenges, which, while not appearing to slow the pace at which the SEC is filing enforcement cases, could have implications for the SEC’s efforts to regulate the professionals who practice and appear before it.

Digital Asset Enforcement is Booming

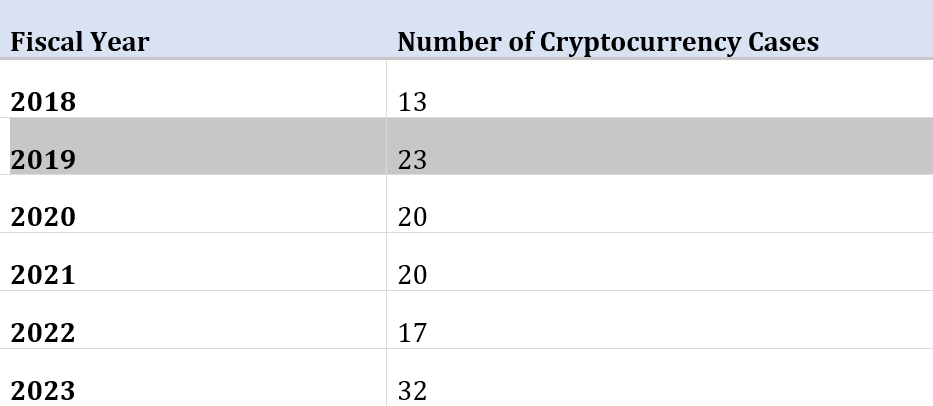

The SEC announced last year that it was nearly doubling the size of the Crypto Asset and Cyber Unit, the enforcement group primarily focused on cryptocurrencies and other digital assets. Not surprisingly, enforcement cases and investigations involving these assets have since surged. The SEC filed 32 separate digital asset enforcement cases during fiscal 2023, the most it has filed in any year since CACU was formed in September 2017 and eclipsing the prior peak by more than a third.

Curiously, the pace of filings during 2023 slowed sharply as the year progressed, with just 10 cases filed after March 31. While there was no obvious reason for this, it could be that the high volume of cases filed during the first half of the year was in response to the well-publicized collapse of high-profile crypto trading platforms, algorithmic stablecoins and high-yield lending programs that occurred during calendar year 2022.

The increased filing numbers, however, tell only part of the story. This year saw the SEC shift focus toward structural aspects of the crypto markets, with less emphasis on individual cryptocurrencies and initial coin offerings. For instance, the agency brought its first case involving proof-of-stake services, which are part of the process for validating new cryptocurrency transactions.Soon after, the SEC charged another leading cryptocurrency firm for offering proof-of-stake services to customers, as well as for allegedly acting as an unregistered national securities exchange, broker-dealer and clearing agency. The SEC then accused the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange of violations ranging from alleged registration failures to purported misrepresentations about its safeguards against manipulative trading. These actions reflect a clear shift away from the SEC’s historical focus on policing individual unregistered cryptocurrency offerings and toward actions likely to affect the broader digital assets market.

The SEC also brought its first two enforcement actions involving non-fungible tokens, signaling its intent to scrutinize digital assets beyond cryptocurrencies. Each case alleged only registration violations, which the NFT issuers settled without admitting wrongdoing. The SEC deemed the NFTs to be securities in the form of investment contracts and provided some (if conclusory) analysis of the facts relevant to the Supreme Court’s Howey test. But both actions drew dissents from the SEC’s Republican commissioners, who disagreed with the agency’s application of Howey and, in one matter, expressed concern that the agency’s enforcement-first approach threatened to “discourage … content creators from exploring ways to harness social networks to create and distribute content.” Without further guidance from the SEC, it is unclear whether these cases represent a new front in the SEC’s enforcement campaign against digital assets or were driven simply by their unique circumstances.

The SEC’s litigation experience with digital assets during the year was decidedly mixed. Most prominently, it lost a major piece of its long-standing Ripple Labs litigation when the court granted summary judgment to the defense on claims based on blind bid/ask transactions through exchanges, which comprised the largest part of the SEC’s case. The court concluded that the SEC had failed to present evidence showing that these purchasers had a reasonable expectation of profit from the efforts of others, as required under Howey’s third prong. The SEC arguably regained some of this ground a few weeks later when a different judge in the same district denied a motion to dismiss the SEC’s complaint and sought to distinguish Ripple Lab’s application to blind bid/ask transactions on exchanges.But this reprieve proved fleeting when the Ripple Labs court later harmonized the two decisions in its order denying the SEC’s motion for interlocutory appeal. The reasoning in this decision is likely to be influential in other cases, especially those involving cryptocurrency trading platforms alleged to have acted as unregistered securities exchanges.

Internal Controls Enforcement is Expanding

Claims for internal controls violations have long been components of SEC accounting and disclosure fraud cases but were typically ancillary to the misrepresentation and omission charges at the heart of those cases. But continuing a trend from last fiscal year, the SEC is increasingly willing to charge internal controls violations as the centerpiece of a case, without any accompanying fraud or misrepresentation claims. For instance, the SEC brought a settled case alleging that Exela Technologies Inc. and its CFO had not disclosed certain related party transactions and improperly accounted for and disclosed a shareholder appraisal action. Although the alleged errors resulted in a restatement, the SEC did not charge fraud or misrepresentation but instead focused on the deficient accounting and disclosure controls that led to the errors. The SEC likewise limited its charges against Plug Power Inc. to accounting and disclosure control violations, despite a multiyear restatement of the company’s financial statements. And the SEC reached the same result in a settled action against Gentex Corporation and its chief accounting officer over allegedly improper executive bonus accruals. Although the SEC’s Gentex order implied that some of the accruals were part of an earnings management effort, the agency only charged alleged accounting controls failures, coupled with reporting and record-keeping violations.

More concerningly, the SEC has pursued internal controls charges in cases lacking evident material misstatements or investor harm and has leveraged internal controls rules to police conduct outside of its purview. A case in point is the SEC’s settled action against Activision Blizzard Inc. in which the SEC did not allege that the company’s financial statements or disclosures were misstated or misleading in any way. Instead, the SEC asserted only that the company’s disclosure controls and procedures had failed to capture information about alleged sexual harassment claims that, in some unspecified way, could have been relevant to Activision Blizzard’s assessment of its risk disclosures about employee retention. The SEC fined the company $35 million for these alleged shortcomings, as well as for unrelated alleged violations of the SEC’s whistleblower protection rules. This penalty is difficult to reconcile with those imposed in Exela ($175,000), Plug Power ($1.25 million) and Gentex ($4 million), where the alleged internal controls failures purportedly led to material misstatements and omissions. This suggests that the penalty was intended to punish conduct — alleged sexual harassment — that the SEC found offensive but over which it lacks jurisdiction. If so, then Activision Blizzard signals a potentially troubling turn in the SEC’s view of its authority.

The SEC’s Whistleblower Program Takes Center Stage

Whistleblowers are crucial to the SEC’s enforcement efforts, a point echoed by SEC officials and reflected in the recent growth in the number and amount of awards. The results in fiscal 2023 were no exception. The SEC received more than 18,000 tips and paid nearly $600 million in whistleblower awards during the year, its most ever, including the single largest award in its history — $279 million to a single claimant.

It is no wonder, then, that whistleblower protection is a top enforcement priority. Fiscal 2023 saw the SEC bring five whistleblower protection cases, as many as it had filed in the previous two fiscal years combined. These cases alleged violations of Exchange Act Rule 21F-17 by public and private companies whose severance or other employment-related agreements included provisions that the SEC alleged could impede individuals from communicating directly with SEC staff about possible securities law violations. Most of these cases involved terms that the SEC had flagged as improper in previous enforcement actions, such as requirements that employees inform the company whether they have communicated with the SEC or that they forego monetary awards for providing information to the SEC. A key difference from the earlier enforcement actions, however, is that the companies in this year’s cases also made efforts to expressly advise employees of their right to communicate with the SEC notwithstanding contrary contractual limitations. The SEC nonetheless found these admonitions insufficient to offset the alleged inhibitions imposed by the other contractual terms. The SEC’s reliance on whistleblowers shows no signs of abating — particularly given the enormous number of tips being submitted to the SEC — so employers should expect to see the agency continue to prioritize aggressive whistleblower protection efforts.

Uncertain Direction of ESG Enforcement

The SEC created the ESG Task Force in March 2021 to focus on climate and ESG issues from an enforcement perspective. During fiscal year 2022, the SEC brought five cases under the ESG Task Force’s umbrella, the highest profile of which involved claims that a Brazilian mining company had misled investors about its safety record ahead of the catastrophic failure of one of its waste-containment dams. But during fiscal year 2023, the SEC filed only three cases arguably falling under the ESG rubric, two of which involved settled proceedings against investment advisers for allegedly not following published policies and procedures for ESG investments. Curiously, the SEC also listed Activision Blizzard as an ESG matter, despite failing to connect any social or governance issues at that company with misstatements or omissions to investors.

Still, it seems unlikely that the relative slowdown in case filings signals that the SEC has lost interest in ESG enforcement. To the contrary, press reports reflect that the SEC recently subpoenaed investment advisers for information about their ESG marketing activities. It could be simply that these cases are challenging and time-consuming to investigate, given the often forward-looking, imprecise, and aspirational nature of many climate or ESG claims. Alternatively, the SEC could be adjusting its prioritization of ESG issues in response to shifts in political and market attitudes; for instance, the SEC’s Division of Examinations’ newly issued 2024 Examination Priorities report dropped ESG as a priority for the first time since 2020. Whether the Enforcement Division is similarly reevaluating its approach to ESG remains to be seen.

SEC Administrative Proceedings Remain Under Siege

In April 2023, the Supreme Court unanimously held in Axon Enterprise, Inc. v. Federal Trade Commission that respondents in SEC administrative proceedings can raise collateral challenges to those proceedings in federal district court. The decision overturned decades of circuit court precedent that such challenges could only be brought on appeal to a circuit court from the SEC’s final decision in a case. Axon represents the latest judicial setback for SEC administrative proceedings, continuing a losing streak for the agency that started with the Supreme Court’s 2018 Lucia decision that SEC administrative law judges had been unconstitutionally appointed.

A potentially more serious challenge to the SEC’s administrative powers is looming. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear the SEC’s appeal of the Fifth Circuit’s Jarkesy decision, which sharply curtailed the types of cases the SEC can litigate administratively and questioned the constitutional underpinnings of the SEC’s administrative authority. Oral argument is set for Nov. 29. Like Axon, a Supreme Court ruling in Jarkesy could have significant implications not only for the SEC but across the federal administrative landscape.

While questions remain over whether Axon and Jarkesy — if decided against the SEC — might authorize parties to challenge other SEC administrative activities, such as SEC investigative subpoenas, it is not clear that these decisions will substantially slow the SEC’s overall enforcement program. The SEC largely stopped using administrative proceedings for contested matters several years ago, except where respondents consented to litigate in that forum. But this has not kept it from generating enforcement case numbers and financial sanctions that meet or exceed historical norms.

One area Axon and Jarkesy could affect, though, is the SEC’s oversight of the professionals who practice or appear before it. The SEC normally does this through proceedings under Rule 102(e) of its Rules of Practice, which allows the SEC to bar, suspend or censure professionals practicing or appearing before it and can only be pursued administratively. While relatively few of these proceedings were litigated historically, that could change, particularly given the severe career and business implications that a Rule 102(e) suspension can have for a person or firm. Respondents may be emboldened to resist the SEC’s settlement demands for lengthy suspensions, recognizing that any administrative proceeding the SEC brings now can be attacked collaterally through district court actions. In turn, this could temper the SEC’s settlement expectations as it seeks to avoid further curtailments of its administrative authority.

Notably, however, the SEC filed a federal district court action at the end of fiscal year 2023 against an accounting firm for violating auditor independence rules and for aiding and abetting its clients’ federal securities law violations. Whether this is the SEC’s new blueprint for policing the professionals who appear before it likely depends on the outcome in Jarkesy, but pursuing district court actions will almost certainly take longer and entail a higher evidentiary burden than the SEC faced in its administrative forum.

David Peavler and Evan Singer are partners in Jones Day’s Securities Litigation & SEC Enforcement practice, resident in the Dallas office. Camden Douglas and Kayla Evans are associates in Jones Day’s Dallas office who contributed to this article. The views and opinions set forth herein are the personal views or opinions of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect views or opinions of the law firm with which they are associated.