Executives at Texaco woke up Nov. 20 — exactly 40 years ago today — like it was the morning after aliens attacked in the movie Independence Day.

“Total destruction,” according to Dick Miller, Texaco’s lead trial lawyer.

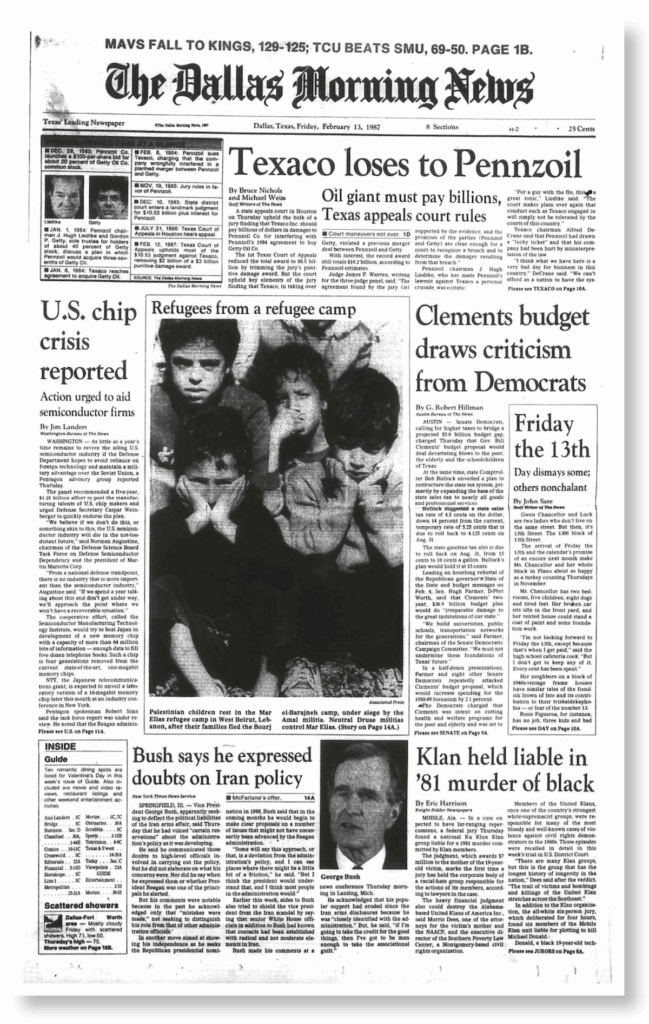

The Houston jury, a day earlier, had ruled the New York-based oil and gas giant had tortiously interfered with a 1984 agreement Getty Oil made to merge with Pennzoil and awarded Pennzoil $10.53 billion — the largest jury verdict in U.S. history at the time.

Texaco’s stock took a beating — dropping from $80 per share when the litigation started to $32 the week following the trial. Some Wall Street analysts were openly warning about bankruptcy. The company’s convertible bonds plummeted in value. Texaco’s debt rating was cut by Standard & Poor’s. A Salomon Brothers bond trader called it “a panic situation of which nobody knows the full impact.”

And there were other unforeseeable, mounting issues. Top among them: The interest accruing on the judgment was $2.8 million every single day.

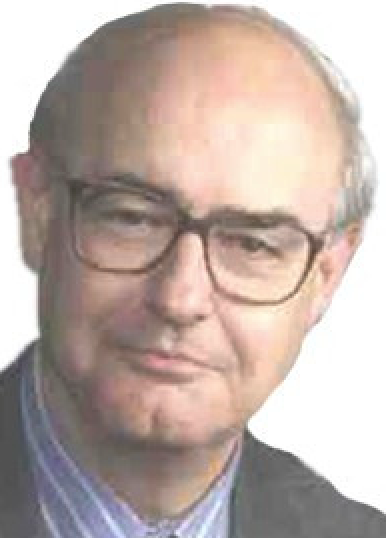

“Texaco and its lawyers for some reason truly thought they would win the trial,” retired Vinson & Elkins partner Harry Reasoner told The Texas Lawbook in a recent interview. “As an outsider watching the trial unfold, it was clear that Pennzoil had the better facts and the better arguments.”

Reasoner would not remain an outsider for long.

For the first few days after the Houston jury’s Nov. 19 verdict, Texaco remained defiant, attacking the verdict. Company executives insisted in public statements that it was business as usual for the energy firm.

“We feel very confident that there is no way that this outrageous travesty can withstand a judicious appeal,” Texaco General Counsel William Weitzel stated at an analyst meeting on Nov. 20, 1985. “If there is any justice in the system, we will come out a winner.”

Seventy-two hours later, Texaco did a public about-face, describing the verdict as potentially threatening the multibillion-dollar oil company’s existence.

Between Thanksgiving 1985 and Christmas 1987, the two energy companies and their ever-expanding roster of litigators did battle. The litigation itself multiplied, including a precedent-setting federal case in New York over Texaco’s appeals bond, a monumental appellate battle, a bizarre decision by the Texas Supreme Court, the world’s largest corporate bankruptcy at the time and a historic settlement.

“It was really a fist fight every step of the way,” retired Baker Botts partner Irv Terrell said. “It was like nothing I had ever seen or heard about before or would ever experience again.”

Both sides hired major reinforcements — fresh legs and fresh eyes, if you will — as the trial teams had been going full speed for 21 straight months. The appeals team for Texaco beefed up with several heavy hitters from Fulbright & Jaworski and David Boies of Cravath in New York. Pennzoil added a Texas superstar in V&E’s Reasoner and Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School.

Neither side had much appetite for settlement negotiations, according to Joe Jamail, Pennzoil’s lead trial lawyer, in an interview with The Texas Lawbook a few months before he died in 2015.

“Texaco still was not admitting how much they had fucked up, so why would we want to even meet with those bastards,” he said.

Despite winning the largest jury verdict in history on a contingency fee agreement, Jamail kept festivities low-key, though he gave interviews to The New York Times, The Dallas Morning News and The Wall Street Journal — all proclaiming him the lawyer who took down Wall Street titans.

In part one of this series of articles on the 40-year legacy of Pennzoil v. Texaco, The Lawbook provided an in-depth timeline of the events leading up to the historic trial and the trial itself.

In part two, The Lawbook provides a detailed timeline of the legal developments throughout the appeal, which were equally historic, but are often overlooked.

“As one of my former partners used to say, ‘We scored the largest remittitur in U.S. history,” said Norton Rose Fulbright partner Steve Dillard.

Gearing Up for the Appeal

Nov. 23

Texaco regrouped for the appeal by making two major hires. The first was New York trial lawyer and Cravath partner Boies, who represented CBS News in a libel lawsuit brought by U.S. General William Westmoreland.

“The consequences of this enormous judgment are severe, not only to Texaco and its shareholders and employees but also to the system of business in this country,” Boies told The Houston Chronicle.

The second engagement was a team of about 30 lawyers from Fulbright & Jaworski. Fulbright — now Norton Rose Fulbright — had represented Texaco for years on various litigation matters and agreed to work with Miller and Boies on the appeal.

Dillard said he received a call at home from his law firm’s managing partner, Gibson Gayle, the Sunday before Thanksgiving.

“Are you going out of town for Thanksgiving?” Gayle asked.

Dillard said he had no plans.

“Good, we need you to go to New York this week because there’s going to be a board meeting at Texaco,” Gail told Dillard.

The “week in New York” turned into thousands and thousands and thousands of billable hours over the next two years for Fulbright.

Dillard worked with Gayle and lead litigation partner Jim Sales in reviewing the trial transcripts and trial court documents, especially as they related to the damage award.

“There were some very intense nights and weekends and holidays,” Dillard told The Texas Lawbook. “We were on the cutting edge of the law and it was consequential. Frankly, it was exhilarating for the lawyers.”

Dillard and the Fulbright team were able to provide the client, Texaco, with viewpoints not tainted by being in the midst of war during the trial.

“If you look back at the verdict, the fact that you have a $3 billion punitive damage award, the jury did not like what it saw,” he said. “Even though it was Texaco’s strong view then and forever that there was not a binding agreement, the jury obviously did not like the financial advisors. That was quite obvious. And Joe did a masterful job at painting them as villains.”

Texaco lawyers privately developed a strategy to let all the drama and publicity around the trial and the verdict settle down for a few weeks before publicly addressing the issues ahead on the appeal.

But that didn’t happen.

Nov. 24

The Houston Chronicle published a huge article that covered the Sunday newspaper’s Outlook Section written by James Shannon, a key juror in the Pennzoil v. Texaco trial.

“I wish those who criticized the award could have sat through the trial the way I did as a juror,” Shannon wrote. “They would have known that Texaco never disputed Pennzoil’s damage claim of $7.53 billion.”

The juror took special aim at Wachtell Lipton partner Martin Lipton, a lawyer for the Getty Museum who testified at the Texaco trial.

“Lipton not only admitted he was a fast-talking dealer, he bragged about it,” he wrote. “Even as he had lawyers from his firm working on the final documents, Lipton was on the phone with his former client, Texaco, working to undo the deal. By the time Lipton appeared as a witness, the jury had heard hundreds of hours of testimony about what had happened.”

“If attorneys for Texaco were hoping that Lipton could salvage their case, they were sorely disappointed,” Shannon wrote. “By the time Marty Lipton left the stand, he had driven the last nail in Texaco’s coffin.”

Feeling the sting of the Houston Chronicle, Texaco decided to provide one of its executives to the other major newspaper in Texas, The Dallas Morning News, for an interview.

Nov. 25

In a page-one article, Texaco President Alfred DeCrane told The Dallas Morning News that the oil giant didn’t have the money to post an appeals bond.

“If a $12 billion bond is required, Texaco doesn’t have $12 billion and, in my opinion, probably can’t get it,” DeCrane said. “We’d have to look for some heroic measure — whether it is Chapter 11 or whatever.”

The story blinded Wall Street and investors. More rumors of potential bankruptcy erupted.

Texaco decided to focus on the first post-trial hearing before District Judge Solomon Casseb, who had taken over the case in October when the original trial judge had to step away due to illness.

Nov. 27

Jamail, Baker Botts and Pennzoil added their own superstar to the plaintiff’s appellate team in V&E partner Reasoner.

“I knew if I needed one lawyer to help us get this verdict across the finish line, it was Harry,” Jamail told The Lawbook in 2015. “There is no smarter, no better legal mind in Texas or anywhere else than Harry.”

Houston trial lawyer Richard Mithoff, who was law partners with Jamail and friends with Reasoner, said Jamail and Reasoner first met across the litigation table from each other when Reasoner snatched a victory away from one of Jamail’s clients.

“Joe came into the office one day yelling, ‘Who the hell is Harry Reasoner?’ I told Joe that Harry is a damn great lawyer,” Mithoff said. “Sometime right after that, the two became friends.”

Even lawyers who knew both men thought the friendship between Jamail and Reasoner was odd because of their absolutely opposite courtroom styles.

“Everyone thought Harry and Joe were the Felix and Oscar of The Odd Couple,” said Rob Walters, a former V&E partner with Reasoner. “Joe and Harry admired each other, and they had a special friendship. In many ways, Harry was everything Joe could never be, and Joe knew it and was fine with it.”

Former Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Hecht knew both men and was friends with them.

“Joe invited four of us to his home one evening — Harry and Macey, Priscilla and me,” said Hecht, referring to his wife, U.S. Fifth Circuit Judge Priscilla Richman, and Reasoner’s wife Macey. “I realized that Joe loved and needed Harry because of Harry’s calmness and steadiness. Harry is always strategic. Harry reminded us that the objective for lawyers is not to fight; the object is to win.”

For his part, Reasoner said that Jamail was the general of the appellate team, but that the lawyers at Baker Botts did not get the credit they deserved.

“The lawyers at Baker Botts, John Jeffers and Irv Terrell and so many others, did extraordinary work on this case,” Reasoner said. “Baker Botts had been Pennzoil’s long-time outside counsel, and those lawyers brought an extraordinary amount of knowledge to the litigation. The firm worked hard and deserved a ton of the credit.”

“Meanwhile, Joe was just Joe, being a great advocate and charging forward,” he said.

Dec. 5

Gayle of Fulbright opened the hearing by telling Judge Casseb that the verdict “threatened the very existence of a major United States corporation.” He said the prospect of having to post a $12 billion bond was “an enormous economic threat” to the company’s 55,000 employees and 300,000 stockholders.

Boies argued the legal grounds: there was no formal agreement.

“Whether it was a business obligation or a moral obligation does not matter,” Boies argued. “Under New York law, it must be a written agreement.”

Jamail responded, “If you steal big enough money or get hurt big enough, corporate America, don’t worry; you won’t have to pay.”

Irv Terrell reminded Judge Casseb that when Texaco agreed to indemnify Getty Oil executives, it assumed legal responsibility for any damages Getty executives caused against Pennzoil.

Dec. 6

Public matters for Texaco became worse when prominent Wall Street Journal columnist James Stewart — now the lead business columnist for The New York Times — published a column exposing that Texaco had hired Fulbright, Cravath and Kaye Scholer, promising each of them that they would be the lead lawyers for the company’s appeal. Lawyers for all three told reporters their firms were calling the shots.

“The turmoil doesn’t surprise me with this bunch of sorority girls,” Stewart quoted Jamail as saying.

Dec. 10

Texaco lawyers presented Judge Casseb with about four hours of argument seeking to have the $10.53 billion judgment reversed or at least significantly reduced.

They got neither.

Judge Casseb entered a final judgment of $11,122,967,110.83, which included interest. But the judge reduced the jury’s pre-interest judgment by about $800 million. The judge also prohibited Pennzoil from seizing assets based on the judgment until after Texas had filed its motion for a new trial, and he prohibited Texaco from selling any of its assets without court approval.

“Pandemonium broke out in the packed courtroom,” the Houston Post reported.

The Wall Street Journal reported that the courtroom was full of investors and stock traders, each with a portable cell phone, ready to place buy or sell orders, depending on how the hearing went.

“We’re going to pick Texaco clean like a Thanksgiving Day turkey and then hang the Texaco star on our Christmas tree,” one trader told The Journal.

Dec. 16

Texaco sued Pennzoil in U.S. District Court in White Plains, New York, arguing that it was being denied its federal due process rights if a state court in Texas required it to post an appeals bond of $12 billion. The lawsuit also asked the federal court to prevent Pennzoil from seizing its assets pending the outcome of the appeal.

“We had the realization that there was not a sufficient bond capacity in the entire world to supersede this judgment,” Dillard said.

Dec. 18

A judge in the Southern District of New York granted Texaco’s request for a temporary restraining order.

Dec. 19

Several shareholder lawsuits were filed in Texas and Delaware against Texaco and its investment bankers at Goldman Sachs.

Jan. 7

Pennzoil’s board of directors rejected a proposed settlement offer by Texaco in which Texaco would buy Pennzoil, according to multiple news reports.

Jan. 9

Texaco filed a motion for a new trial and asked Judge Casseb to step aside because he was not qualified to handle the case. The motion also cited hundreds of errors committed by the court during the trial and argued that Pennzoil lawyers had made inflammatory remarks that inflamed the jury.

Jan. 10

U.S. District Judge Charles Brieant in New York granted Texaco its preliminary injunction that kept the oil giant from having to post an appellant bond of the verdict in Houston. Judge Brieant ruled that “the concept of posting a bond of more than $12 billion is just so absurd, so impractical and so expensive that it hardly bears discussion.” Instead, the judge required Texaco to post a $1 billion bond.

Jan. 29

An administrative judge in Texas rejected Texaco’s petition to remove Judge Casseb from the Pennzoil v. Texaco case.

Feb. 4

The 14th Houston Court of Appeals rejected Texaco’s appeal to remove Judge Casseb.

Feb. 20

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit upheld the lower federal court’s decision to allow Texaco to pursue its appeal without having to post a full $12 billion bond.

Feb. 21

In a two-minute court hearing, Judge Casseb denied Texaco’s petition for a new trial and declined to hear arguments from lawyers for Texaco on why they deserve a new trial.

March 20

Pennzoil appealed the Second Circuit’s decision favoring Texaco on the appeals bond issue to the U.S. Supreme Court.

April 23

Texaco appealed the $10.53 billion jury verdict to the First Court of Appeals in Houston.

In its appeal, Texaco cited 90 errors committed by the trial court that prevented the oil giant from receiving a fair trial.

“The special issues and instructions that were presented to the jury were adopted virtually verbatim from Pennzoil’s submissions,” the Texaco brief argued. “They are tainted with numerous direct comments on the weight of the evidence and assumptions of stated fact. The charge for jury instructions did not just tilt or nudge but shoved the jury toward Pennzoil’s desired result.”

Baker Botts partner John Porter, who was fresh out of law school in May 1986 and worked on the brief even before he took the bar exam, said Pennzoil’s response brief was 400 pages, which caused the firm’s computer — an IBM 2000 that worked on floppy discs — to freeze up.

“We ended up having to print it as two separate documents,” he said.

May 4

The Getty Oil Museum, which owned 11 percent of Getty Oil stock that was sold to Texaco, sued Texaco, claiming the New York energy company was not honoring its agreement to indemnify all the officers in litigation related to the Getty Oil, Texaco and Pennzoil fiasco.

“The Texaco suit shows the company won’t honor its indemnities,” Jamail told The Los Angeles Times. “I wonder how that’s going to look before the U.S. Supreme Court.”

May 23

Texas Attorney General Jim Mattox said he would not file an amicus brief in the U.S. Supreme Court case on the issue of state court-ordered appellate bonds.

June 12

Pennzoil filed its response to Texaco’s appeal in the Houston First Court of Appeals, stating that Texaco’s arguments were “a myriad of hyper technical complaints” about the judge’s charge to the jury.

The Houston Chronicle reported that Jamail asked the clerk of the appellate court to keep the court’s office hours open late because the law firms were having problems printing the 373-page brief.

June 23

U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear Pennzoil’s appeal from the New York federal courts regarding Texaco’s bond. Pennzoil’s lead lawyer in the Supreme Court argument, Harvard Law professor Tribe, told the justices in the petition for certiorari that New York’s decision was “an unprecedented intrusion by a federal court into ongoing state court proceedings.”

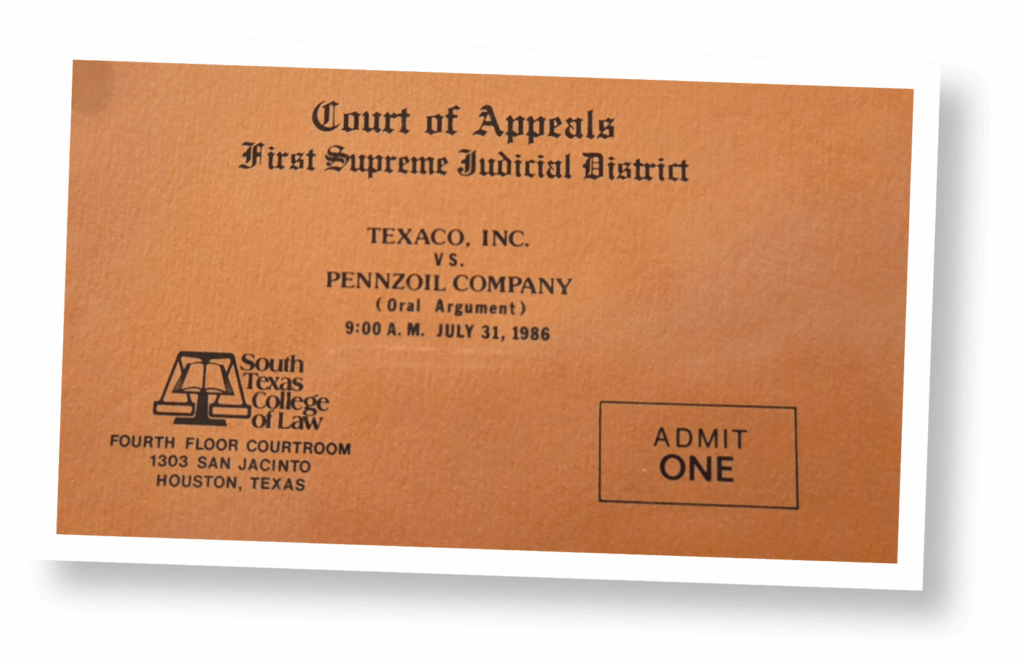

July 30

The First Court of Appeals in Houston heard oral arguments in Texaco’s appeal of the jury verdict.

Due to the public and legal community interest in the case, the state appellate justices moved the oral arguments out of the courthouse to a 750-seat auditorium at South Texas College of Law in downtown Houston.

“The only reason we are doing it is there is not enough room in our own courtroom to seat the lawyers involved,” court clerk Kathryn Cox told The Chronicle.

Lawyers for each side were provided 125 tickets for entry. The day before the argument, the law school added an adjacent room that seated another 250 people who watched via closed-circuit television. In the end, 940 people attended the argument.

Texaco attorney Jim Sales, a partner at Fulbright, argued that Judge Casseb never familiarized himself with the case when he entered the trial more than halfway through its course. Judge Casseb took over from the original judge, who became ill three months after court proceedings began.

“Casseb admitted … he could not and did not read the transcript and he was not up to speed on New York law,” Sales told the three-justice panel. “At this point, Pennzoil took advantage of Casseb’s unfamiliarity. It’s the old bit of, ‘You let me ask the questions and give instructions, and I can get you the answer you want every time.’”

Sales also told the panel that Judge Casseb “skewed and nudged the jury into Pennzoil’s camp.”

“The imposition of this outrage on Texaco would, in my opinion, make a mockery of our entire system,” Sales argued.

Each side was given two hours of arguments. Texaco divided it up four ways.

Boies was the next to address the court, tackling the issue of the agreement and whether it was valid.

Justice Sam Bass asked Boies if the two companies would have an agreement if they “came to general terms but then told their lawyers, ‘You fellas go work it out.’”

“I think it would be contingent on their working out,” Boies responded. “The fundamental thing that has to happen first is an intent to be bound.”

For Pennzoil, six lawyers took their turns at the podium.

Simon Rifkind, a former New York federal judge who was then a partner at Paul Weiss representing Pennzoil, told the appellate court that “this case is full of drama, as brazen an interference of a contract as I have ever seen.” He pointed out that he has been a lawyer and judge for more than 60 years.

Then it was Jamail’s turn to address the panel.

“My job was to draft an outline of our arguments for Joe as a guide for him,” said Allan Van Fleet, who was a young lawyer working with Reasoner at Vinson & Elkins. “My first draft was 40 pages, but I cut it to about 15 pages. But I was surprised that Joe, during the oral arguments, got up and just started reading directly from my outline and notes. Fortunately, he did pretty well.”

Jamail told the appellate justices that Texaco’s attorneys were asking “another court for more sympathy.”

“They seem to be saying the wrong is so huge the system cannot absorb it — run away from it,” he argued.

Jamail told the justices that Texaco was like the boy who murdered his parents and then asked for mercy because he was an orphan — an argument that Abraham Lincoln often used in court arguments, according to multiple sources.

“Texaco is trying to bring us back to the law of the jungle,” he said. “They have tried to spread an image of frontier justice, of a trigger-happy posse.”

Jamail also criticized Texaco attorneys for carrying out what he called a media blitz against the Texas court system, judges and jurors who decided the case.

“It’s not poor legal advice or stupid jurors or a flawed Texas judicial system that caused the verdict against Texaco,” he said. “’A very average man or woman confronted with the facts would find exactly what this jury did — it’s a coverup.”

One of the lawyers pointed out that the interest on Texaco’s judgment increased $390,000 during the four hours of oral argument.

Jan. 12

U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on whether Texaco could be forced to post a supersedeas bond while it appealed the jury’s verdict.

Feb. 12

The First Court of Appeals in Houston, in a 162-page opinion, reduced the punitive damage award against Texaco from $3 billion to $1 billion but upheld the actual damage verdict of $7.53 billion.

“We are not authorized by law to substitute our judgment for that of the jury,” the justices wrote.

Texaco lawyers called the decision “absurd” and “appalling” and promised to appeal to the Texas Supreme Court.

“If the seriousness of this doesn’t sink in now, those people don’t have the collective IQ of a geranium,” Jamail told The Wall Street Journal.

April 6

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts, forcing Texaco to post an appeals bond.

April 13

Texaco filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the Southern District of New York.

Sept. 2

Texaco appealed the verdict to the Texas Supreme Court.

Nov. 1

Texas Supreme Court, in a one-page order, declined to hear Texaco’s appeal.

“The fact that the Texas Supreme Court declined to even hear the largest civil case in the state’s history is shocking,” said U.S. Magistrate Judge Andrew Edison, who teaches a course on the law that prominently features the Pennzoil v. Texaco case.

Dec. 19

Texaco settled, paying Pennzoil $3 billion.

“We celebrated that night at my house by eating hamburgers and drinking beer,” Jamail said. “I’ve still got the $3 billion deposit slip on my wall.”

* * *

At a Houston Bar Association event last week, several attorneys who had a connection to the case discussed its impact, both on litigation generally and on them personally 40 years later.

J.C. Nickens, a lawyer with Miller Keaton representing Texaco at the time, pointed to Pennzoil v. Texaco as a bullet in the rivalry between Texas and Delaware to attract business and the recent creation of the Texas Business Courts.

“There’s a real irony that we’re now trying to replace Delaware as a place where corporations should be, and for at least a decade or longer, I think this case discouraged companies,” Nickens said.

At the end of the day, the trial and the appeal transformed business and business litigation, according to University of Houston Law Center professor Lonny Hoffman.

“That verdict not only transformed the lives of all the parties involved, but it reverberated across corporate America, reshaping how deals were done, handshake agreements and boardroom negotiations were viewed,” Hoffman said.