(The following is an excerpt from The Last Trial of T. Boone Pickens by Stoney Creek Publishing. Copyright 2020 Chrysta Castañeda and Loren Steffy.)

I took a deep breath as the elevator doors rolled open to reveal the lobby of the Best Western Swiss Chalet. I’d long since gotten over the irony of the name. The Swiss Chalet was located in the most un-Switzerland-like spot on earth. Pecos, Texas, sits on the eastern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert, tucked under the arm of New Mexico, and its barren vistas, tumbleweeds, and blazing heat reinforce almost every Hollywood stereotype of Texas.

The lobby decor, with its Alpine photos and display cases jammed with beer steins, provided a jarring contrast to the hardscrabble prairie and trucks carrying massive drilling equipment zipping by on the freeway just outside the front door.

As a lawyer who specializes in fights over oil and gas rights, I’d spent my fair share of time in dusty little towns in the middle of nowhere. There’s an old industry saying that oil isn’t found in pretty places, and that’s mostly true. It’s relegated to deserts and badlands and seabeds deep below the surface of the unrelenting oceans. And when drilling deals in those remote areas go bad, when the partners get into a dispute they can’t resolve, they call me.

That’s how I wound up in the Swiss Chalet. This, however, was no ordinary dispute. I was the lead trial lawyer representing T. Boone Pickens, an industry legend who had spent decades drilling for oil and gas around the world before becoming the dean of the corporate takeover game in the 1980s. He’d lost his first fortune in the 1990s, then built a new and much bigger one in the 2000s. Now, he was suing a group of companies that he claimed had cut him out of a lucrative oil deal in the Permian.

It was early evening, and it had been a long slog at the courthouse. The trial was in its fourth day, and we’d scheduled a meeting for the nearly twenty people on our trial team every day after court recessed so that we could review what had happened and discuss the plan for the next day.

Pickens didn’t believe in leaving details to others—especially if they affected his fortune. He was absorbed in every aspect of the case and he had his own views on all of it. At eighty-eight, he was mentally sharp and didn’t hesitate to share his opinions.

“No one, not even Pickens, realized how big the Permian dispute was when it started. To be honest, that’s the only reason he hired me to represent him.“

The problem was, his time and attention to the details of the trial came at the cost of my time, which already was in critically short supply. I had to prepare comprehensive outlines of questions and assemble the documents we needed to examine the witnesses who would take the stand the next day and every day until we were finished. Normally, for a case this size, the lead trial attorney would leave most of that work to other lawyers, but I am not typical. Like Pickens, I do things differently.

No one, not even Pickens, realized how big the Permian dispute was when it started. To be honest, that’s the only reason he hired me to represent him. Pickens’ right-hand man would tell me later that they would never have chosen a solo practitioner if they had known how much money was at stake in the matter.

When they picked me, I didn’t have a large staff or junior partners working for me like when I’d been a partner with a big law firm. While I did have other lawyers helping me with this trial, I had assembled them ad hoc after Pickens’ in-house attorney and I realized we wouldn’t reach a settlement and were headed for the courthouse.

All of which meant that I hadn’t worked with most of the other members of my team for more than a few months leading up to the trial, and I had a lot riding on the outcome. I’d formed my own law firm a few years earlier, and this was the first major case I’d accepted. A victory for Pickens would cement my fledgling firm’s credibility. I couldn’t leave anything to chance, especially not the intensive preparation required to cross examine the defense witnesses effectively. The other lawyers on the team didn’t have as much experience as I did with oil and gas issues, and at the moment, I was worried about how things were going.

I tried to put all these thoughts out of my head as I headed to the conference room where Pickens and the rest of the team were waiting. I braced myself for what I knew would be a longer conversation than I had time for. Our unconventional tactic of leading with a hostile witness was not succeeding.

We had already presented our opening arguments that laid out the key points of the case. Pickens and his company, Mesa Petroleum Partners, had entered into an agreement in 2007 with other companies that gave Pickens a 15 percent stake in a drilling deal near Pecos known as the “Red Bull.” The parties set out to acquire enough oil and gas leases to be able to drill wells in the geologic formation called the Delaware Basin, which is technically a “sub-basin” of the Permian. When the well results came in, the group hoped they would prove that the area was a good place to produce massive quantities of oil, driving up the value of the investment. Pickens agreed to help pay for the costs of acquiring the leases and drilling the wells, and in exchange, he would get a 15 percent ownership interest, as well as 15 percent of any profits.

At the time the deal was signed, the Permian seemed to have played out. Its production was declining, and the Red Bull looked like it might be a sickly cow. But fracking reversed the region’s fortunes, and more importantly for us, led to a key discovery in the Red Bull two years after the deal was signed. By the time of the trial in 2016, the Red Bull Prospect we were arguing over had become some of the most sought-after oil and gas acreage in the entire Permian, if not the country.

That’s why, as we contended in our opening statements, the other partners decided to cut Pickens out of the deal. He’d refused to give up his stake unless they paid him, and they wouldn’t pay what he was asking in 2009. Instead, they’d simply decided that Pickens had “opted out” of future participation in the deal and claimed his share for themselves.

He hadn’t even known they’d taken it from him. The other side argued that Pickens had said he wanted out, and that he only changed his mind after the value of the deal soared. But they didn’t have the only evidence that mattered in my mind: a written document signed by Pickens agreeing to sign over his ownership interest to them.

Since we believed the defendants had no credible explanation for how they’d taken Pickens’ share of the deal, so we hoped that first calling one of their executives to testify was a risk that would pay off.

It seemed like a good strategy, but it wasn’t working at the moment. Every few minutes, the defense lawyers interrupted, objecting to a question from my co-counsel, Mike Lynn. When we returned to our respective sides of the room, Mike would try to pick up his questioning, only to be interrupted and pulled into another bench conference. The defense lawyers objected so many times that we lost all momentum.

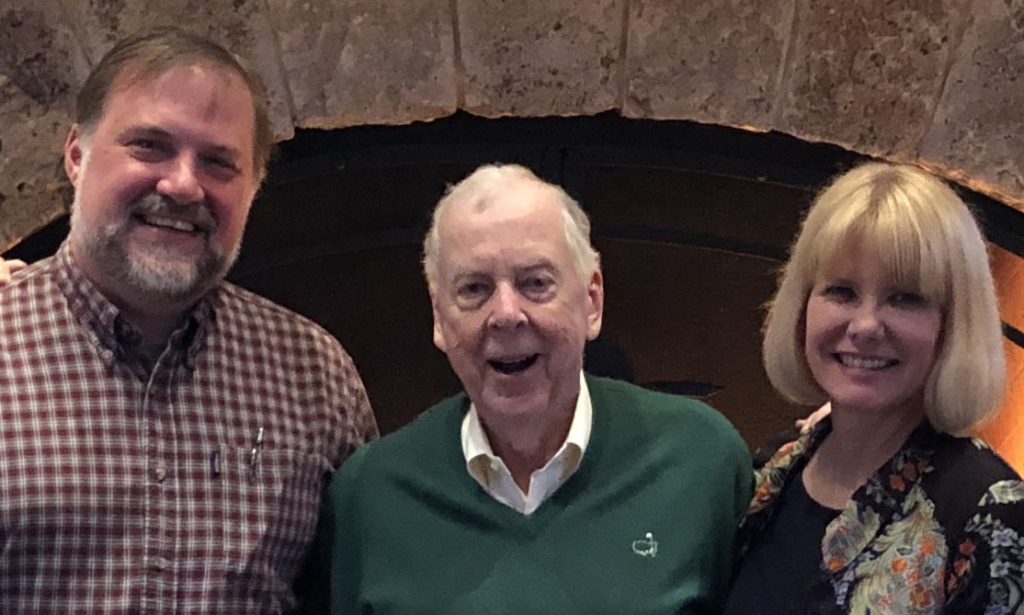

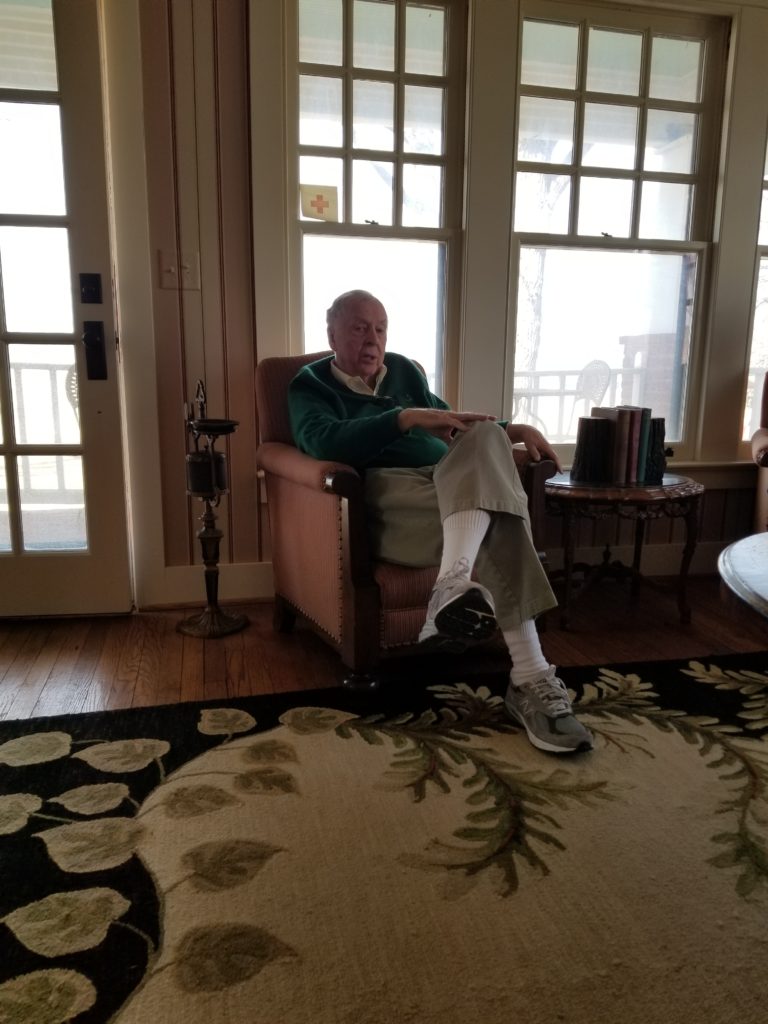

Pickens was on the left side of the table, still wearing his dark gray suit from court. As always, he’d saved the seat next to him for me. He wanted me to sit close because his hearing was failing, and he needed to hear what I had to say about our day in court. His hair was gray and thinning, and he had developed more pronounced jowls in recent years, but his eyes were still a piercing blue.

Pickens started calling the shots as soon as I sat down. A geologist by training, he had an innate understanding of this oil deal and knew how he wanted to establish key talking points with the jury. But he wasn’t a lawyer, and he didn’t know how to examine a witness.

He understood more about oil and gas than all of us combined, including his own geologists. But that wouldn’t be enough to convince a jury that Pickens was right in claiming that he had been illicitly cut out of the Red Bull deal. Pickens had run his own companies since 1956. While he had a congenial side, and he encouraged his subordinates to challenge him, he was also used to having the last word. If he insisted on something, his employees ultimately acquiesced.

The trial was just getting underway, and I worried we already were missing the mark. That evening, everybody in the Swiss Chalet conference room could feel that Mesa wasn’t winning. The rest of my team was sitting in the black vinyl chairs surrounding a wooden table in the center of the windowless space. The front of the room was dominated by a large, flat-panel television that sat silent. Above it, an ornate clock ticked out minute-by-minute reminders of how time was slipping away while we all still had too much to do. For some reason, the conference room was the one place in the hotel that didn’t follow the Alpine theme. The walls were lined with western prints of cowboys and sweeping vistas.

Jurors, however, had power that Pickens couldn’t control. They wouldn’t take his views on faith and they couldn’t be bullied. In other words, the twelve people in the jury box were something alien to a successful businessman like T. Boone Pickens. They didn’t have to listen to him, didn’t have to believe him, and didn’t have to do what he said just because he said it. He would need to persuade them, not through the force of his personality, but through the merits of his testimony and his lawyers’ arguments. If the jurors disagreed, Pickens probably wouldn’t get another try.

His main beef that evening in the conference room was that my co-counsel, Mike Lynn, should be asking different questions. He wanted Mike to zero in on the geology of the drilling prospect, while Mike’s instincts were to focus on big concepts like greed, lying, and cheating. The geological arguments Pickens was running through were not Mike’s area of expertise, and the executive on the stand wasn’t the witness to use them on.

I’d recommended that Pickens hire Mike’s firm to support me during the trial not because of its expertise with geology or oil and gas law, but because Mike had built a formidable team of trial lawyers. His firm, Lynn Pinker Cox & Hurst, had won a $500 million verdict for a pipeline company a couple of years before based on a novel legal theory. The firm also had a stable of trained attorneys and paralegals who could handle all of the tasks a big trial requires. I would supply the leadership, the detailed knowledge, and the overall vision, but my small staff and I certainly couldn’t deliver all of the time and personnel the Red Bull case demanded.

Mike listened politely as Pickens repeated the same information about the geology and the oil reserves at the heart of the dispute. Mike was trying to understand what Pickens wanted to do, but Pickens was becoming frustrated, and Mike wasn’t getting any more adept with the technical points Pickens wanted him to make. Even worse, those points weren’t the ones we needed to emphasize with the defendant’s CEO anyway. We were all wasting time and I had to get this train back on track.

I’d barely stepped into the room and already the conversation was spinning out of control. One other thing about Pickens: he wasn’t used to being corralled. When he spoke, he was accustomed to dominating the room until he had decided he was done. I intervened gently at first, growing more insistent as he kept pressing his points. I told Pickens I obviously was interested in any opinion he had about the case but that arguing about the geological details at this stage was senseless. We needed to concentrate on the terms of the deal because the defendant’s CEO wasn’t going to admit anything about the geological points Pickens wanted to score.

But Pickens kept insisting that Mike should ask questions about geology. I shook my head vigorously, which didn’t help the headache I could feel rising from the base of my neck. I stressed—again—that this wasn’t the witness with whom we needed to make those points. We would state our case, I told him, but we would do it when the time was right. And that time was not now.

“I made a decision. I wasn’t going to back down on my point, and I also wasn’t going to quit the team. Pickens could fire me, but I wasn’t walking away.“

Pickens grew more agitated. The tension in the room was as thick as a blanket but I couldn’t back down. I knew I was right. We had to let Mike focus on what he needed to accomplish—laying out key events in the Red Bull deal—and then move on.

As I pressed my argument with Pickens, the weight of the moment hit me. At fifty-three, I was thirty-five years younger than my big-name client. I was still in high school in Kansas when he commanded national headlines with his famous hostile takeover bid for Gulf Oil. He had brought corporate titans to their knees. He’d tried to shake up the entire structure of Japanese business. He’d met with presidents and governors. He was a king maker in Republican politics, especially in Texas.

But none of that mattered. He was paying me to win this case, to be the general in this war, and he could either listen to me or fire me and find somebody else. The more I told him no, the more frustrated he became.

Finally, he’d had enough: “Stop shaking your head at me!” he shouted. “Don’t argue with me! You don’t know what you are talking about! I’ve been in the business for sixty years! You will listen to me and you will do what I say!”

I stopped talking and just looked at him. How do you avoid telling your billionaire client, the only one you have at the moment because his case takes your entire focus, to shove it?

How do you tell him you aren’t going to be talked to that way? How do you tell him that you, too, have decades of experience at your job, and you, too, know what you’re doing? How do you tell him those things when you are a woman in what, even in 2016, remains firmly a man’s world?

I could feel my face flush. Trial pressures are one thing. Verbal attacks from a client are another. I knew that anything I might say could be disastrous. And I still wanted to win the damn thing, because no matter how petulant or condescending my client was being at the moment, I believed in him. I believed what he had trouble believing himself: that he, the billionaire energy tycoon, the master dealmaker, had been snookered in the biggest oil deal of his life.

A victory for a high-profile plaintiff like Pickens could not only burnish his image and recoup the millions he was owed, but it could also send a message to those who might in the future try to take advantage of others who had far less expertise. Besides, despite the fact that he could be cantankerous and that our political views were polar opposites, I genuinely liked him, and I knew he liked me. I wanted to help him. We could win this case if he would just let me right the ship.

I said nothing. I think in that moment I literally bit my lip. Then, I stood up calmly and turned toward the door. Over my shoulder, I could hear Pickens still shouting: “Turn around and sit down! Don’t you dare leave this room!” He didn’t say “young lady,” but he might as well have.

I was in the doorway, and I looked back over my shoulder. I was angry, but I managed say, with only a slight quaver in my voice, “I’m going to get some water.” Then, I walked out.

The hotel had a water dispenser at the far end of the lobby, and I filled a plastic tumbler and took a long drink, hoping it would extinguish my anger and help me focus. As I swallowed, I made a decision. I wasn’t going to back down on my point, and I also wasn’t going to quit the team. Pickens could fire me, but I wasn’t walking away. We were in this together until the end as far as I was concerned.

I walked straight across the lobby and into the conference room. We’d see, I thought, if Pickens felt the same way. I was only gone for two or three minutes, but by walking out, I’d reset the tone. Everyone was calmer now, including Pickens. He even looked a little remorseful. “I’m sorry,” he said as I sat down. I apologized too.

He chuckled a bit. “We’re friends, right?” he asked me. I assured him we were. We got back to the discussion at hand, and things went smoothly for the rest of the meeting.

Afterwards, as we were packing up and after Pickens had left the room, one of my jury researchers pulled me aside. Pickens had been livid that I walked out on him, she said. He’d turned to his accountant and barked: “Don’t you pay her for a single minute that she is out of this room!”

Later, when the case was over and we looked back on the incident, Pickens and I agreed that it may have been the best three minutes I’ve ever worked for free.

Dallas trial lawyer Chrysta Castañeda and prominent Houston journalist Loren Steffy teamed up to write The Last Trial of T. Boone Pickens. Details about the book, the authors and purchase information can be found here.