Forty years ago this past Saturday night, Joe Jamail sat at his desk at home in Houston to handwrite his portion of the closing arguments in the multibillion-dollar trial of Pennzoil v. Texaco.

“All of a sudden, I hear a car horn blowing outside my house,” Jamail told The Texas Lawbook in an interview five months before his 2015 death.

A white limousine pulled into Jamail’s driveway. Two of his best friends, singer Willie Nelson and former University of Texas football coach Darrell Royal, jumped out and started begging Jamail to go out drinking with them.

“I told them that I was working on the biggest closing argument of my life — hell, the biggest closing argument of anybody’s life — and that I needed to prepare,” he said. “But they weren’t having any part of it. They kept me up all fucking night drinking. I could barely see the jury the next morning.”

Jamail and his co-counsel at Baker Botts kept the basic argument simple for Pennzoil in a highly complex, four-month trial in which Houston-headquartered Pennzoil accused Texaco of tortiously interfering with its existing agreement to purchase Getty Oil in January 1984.

“We had a deal, and we shook hands on that deal. And in Texas, a deal is a deal,” Jamail said. “These New York Wall Street bankers and lawyers had been playing fast and loose with merger agreements for decades, and they thought they were smarter than the rest of us and could get away with it. Pennzoil said that shit needs to stop now.”

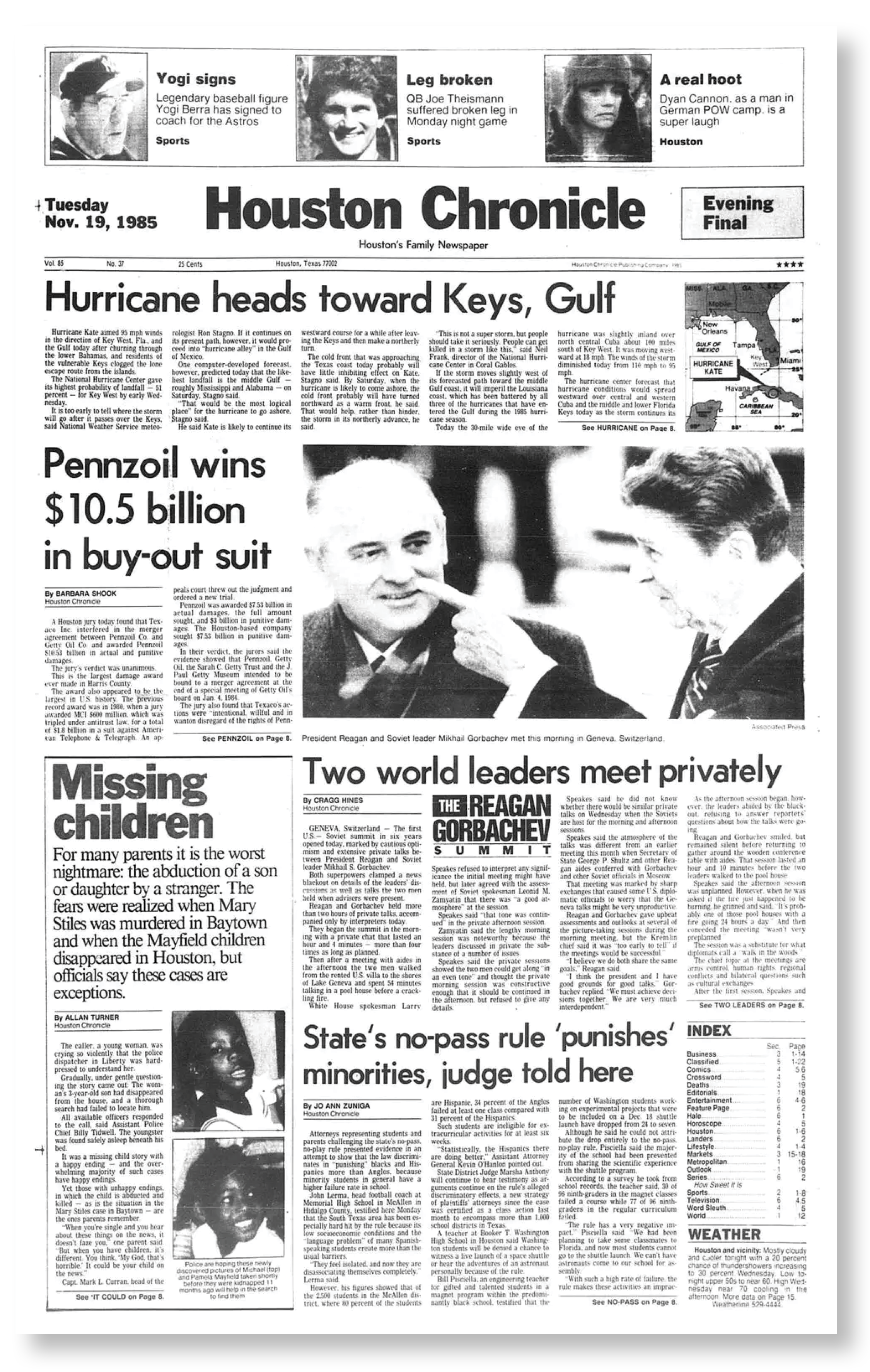

The Houston jury deliberated over three days after four months of trial and returned a verdict in favor of Pennzoil. They awarded Pennzoil $7.53 billion in actual damages and $3 billion in punitive damages — the largest civil jury verdict in history at the time, and still the largest actual damages ever upheld on appeal. That’s $30 billion in today’s dollars.

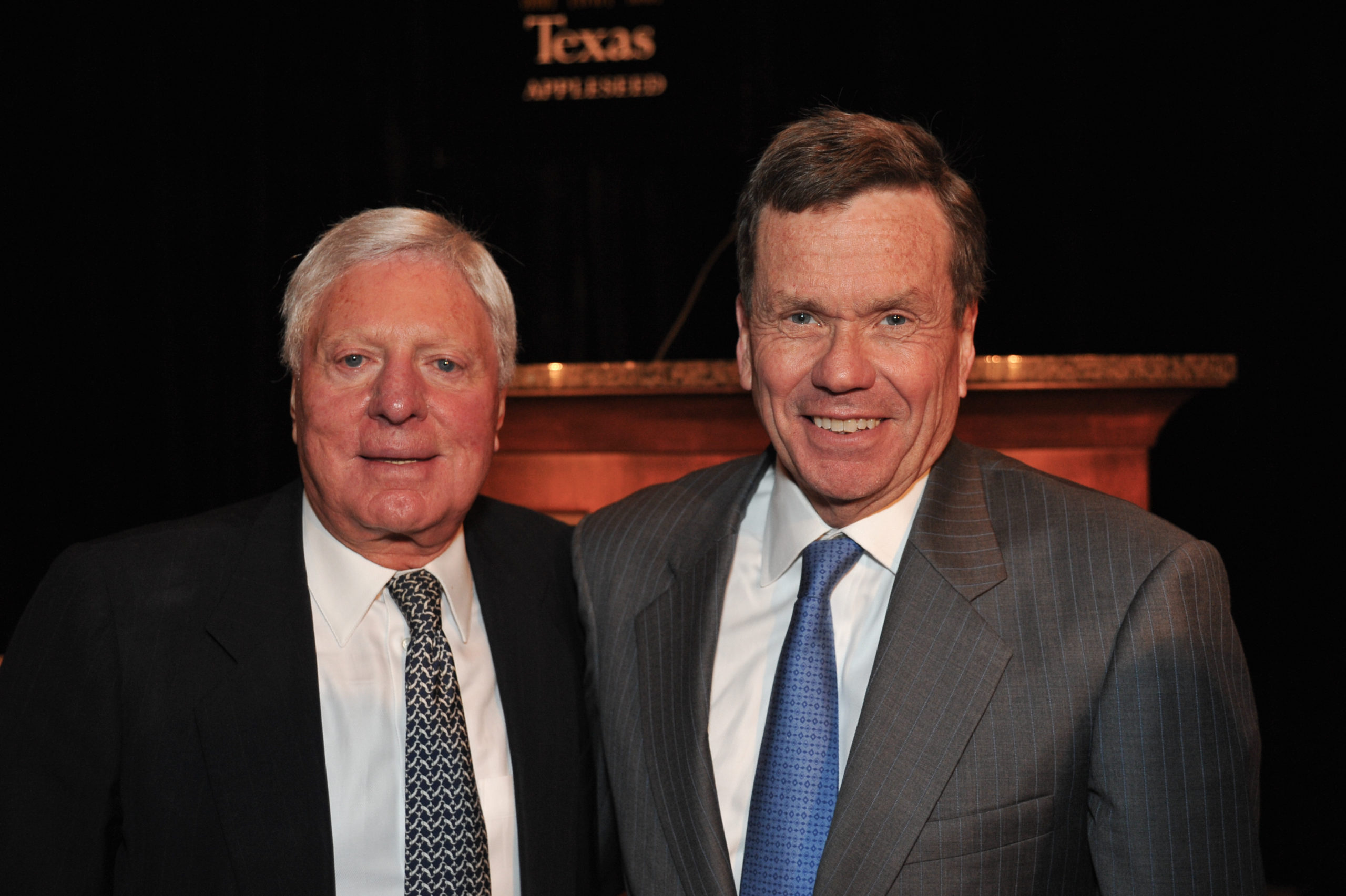

“When the jury award was read, there was stunned silence in the courtroom,” retired Baker Botts partner Irv Terrell, one of the three lead trial lawyers for Pennzoil, told The Lawbook in a lengthy interview last week. “I was absolutely shocked. I thought maybe the jury would compromise and give us $1 billion. It took a few minutes took comprehend.”

As Texas seeks to attract corporations with its new Texas Business Court to compete with Delaware’s Court of Chancery, Pennzoil v. Texaco remains the single most important — and most memorable — corporate merger dispute of all time, according to legal experts. The 1984 Getty Oil and Texaco transaction was, at the time, the largest merger in U.S. history. And legal experts agree that the trial and subsequent appeal dramatically changed how merger agreements were negotiated.

“Most people today do not remember what the case was about — they just remember the $11 billion,” said U.S. Magistrate Judge Andrew Edison of the Southern District of Texas. Judge Edison, who teaches a class on the case at the University of Houston Law Center. “The Pennzoil v. Texaco case had everything: incredibly flamboyant and talented lawyers, enormous companies, fascinating legal and factual issues, and BIG money. It truly was a bet-the-company case in every sense of the word.”

The impact the case had on the Texas legal system was also monumental, including:

- Caused the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to designate Texas as a judicial hellhole in 1986;

- Led to two decades of massive tort reform efforts that dramatically limited the rights of Texans to sue businesses, doctors and insurance companies for wrongdoing;

- Prompted the later sweeping election of Republican justices to the state’s supreme court;

- Sparked a trend among corporate executives to start hiring more plaintiff’s trial lawyers to lead their business disputes against other companies; and

- Propelled Jamail, a highly successful personal injury and wrongful death attorney, into national stardom and led him to become the most successful and wealthiest trial lawyer in U.S. history.

“This case for Pennzoil was the story of business ethics and oilfield honor, while Texaco made it about technicalities and legalities,” said Paul Yetter, who worked on the case as a rookie lawyer at Baker Botts. “The dollar number gets all the attention, but this case was much more. And it featured some of the best lawyers in Texas and across the U.S. doing some great lawyering.”

Multiple books have been written about Pennzoil v. Texaco, including one by a juror in the trial, James Shannon. More than two dozen law review articles have examined the importance of the case. The case — the trial and subsequent appellate decision — has been cited by courts across the U.S. more than 10,700 times.

The transcript of the trial totaled 24,445 pages, and that did not include pretrial depositions, which accounted for another 15,000 pages.

“This is the case that made Joe the richest lawyer in the world,” said retired Texas Supreme Court Chief Justice Nathan Hecht, who was a Dallas County district judge at the time. “The verdict clearly started the whole tort reform movement in Texas. Pennzoil and Texaco became catchwords in judicial campaigns.”

The Pennzoil dispute with Texaco spawned more than two dozen related lawsuits filed before, during and after the jury trial in federal courts in New York and California and in the Delaware Court of Chancery, including 18 derivative actions and the largest corporate bankruptcy in history at the time.

“When it came to business litigation, Pennzoil v. Texaco is the undisputed trial of the century,” said Dallas trial lawyer Frank Branson. “This case showed that no matter how big you are, you are still required to follow the law. And it introduced corporate America to the benefits of hiring trial lawyers — plaintiff’s lawyers — to lead their biggest bet-the-company cases.”

While Jamail garnered most of the attention because of his flamboyance, there were dozens of prominent lawyers who played significant roles in the litigation from Baker Botts, Fulbright & Jaworski, Vinson & Elkins, Cravath, Wachtell Lipton, Paul Weiss and others.

“This was really the litigation Super Bowl,” said Norton Rose Fulbright partner Steve Dillard, who worked on the appeal for Texaco. “It was the biggest case with the best lawyers on the biggest stage with the most at stake.”

“It just had a tremendous impact on M&A practice across the country,” Dillard said at a Houston Bar Association program last week. “There was a law author who referred to it as the Texaco chill that had fallen over mergers and acquisitions and corporate takeovers.”

In this two-part series, The Lawbook interviewed more than a dozen lawyers who were involved in the litigation and another dozen legal experts on the importance of the case. Part One looks at the historic trial and the events leading up to it. Part Two looks back at the appeal, which was equally historic.

Pennzoil Makes a Bid for Getty Oil

The roots of Pennzoil v. Texaco were planted the week before Christmas when executives at Pennzoil saw an opening at Getty Oil.

The final two weeks of 1983 and the first 10 days of 1984 were marked by a furious wave of activity.

Dec. 18

Pennzoil purchased 590,000 shares of Getty Oil stock on the open market.

Dec. 21

Pennzoil announced it had offered $16 billion to purchase 20 percent of Getty Oil at $100 per share. Getty Oil stock was selling for $80 a share.

Jan. 1

Pennzoil founder Hugh Liedtke and Pennzoil President Blaine Kerr, a former Baker Botts partner, met Getty Oil heir and trustee Gordon Getty at 4 p.m. in a hotel suite at the Pierre Hotel, a five-star hotel on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Gordon Getty was the fourth son of oil tycoon J. Paul Getty. After two hours of discussions, the two men shook hands over the terms of the agreement.

Jan. 2

Pennzoil and the Sarah C. Getty Trust and the J. Paul Getty Museum, which also owned Getty Oil shares, signed a five-page memorandum of agreement with the essential terms, which included raising the purchase price by 10 percent to $110 a share. The Getty Trust owned 40.2 percent of Getty Oil shares. The Getty Museum had 11.8 percent of the shares. The Getty Oil board of directors controlled the remaining shares.

Hours later, the Getty Oil board of directors, dissatisfied with Pennzoil’s offer, voted 9-6 to reject Pennzoil’s offer but made a counter-offer. Getty Oil’s investment bankers at Goldman Sachs said the $110 was inadequate.

Jan. 3

The Getty Oil board encouraged negotiations between the lead lawyer for the Getty Museum, Marty Lipton of Wachtell Lipton, and Arthur Liman, lead lawyer for Pennzoil’s investment bank, Lazard. Pennzoil again increased its offer to $112.50 per share. The Getty Oil board voted 15-1 to approve.

Liman, a partner at Paul Weiss, testified later during the trial that he was waiting outside the Getty Oil boardroom that evening and entered the conference room after the board of directors voted to approve the agreement.

“Congratulations, Arthur,” several of the Getty Oil board members told Liman, shaking his hand. “You’ve got yourself a deal.”

Jan. 4

In the morning, Pennzoil and Getty Oil issued press releases announcing an “agreement in principle,” but that final shareholder approval was still required.

“Los Angeles — Getty Oil Company, the J. Paul Getty Museum and Gordon P. Getty as trustee of the Sarah Getty Trust announced today that they have agreed in principle with Pennzoil Company to a merger of Getty Oil and a newly formed entity owned by Pennzoil and the Trustee.”

In the afternoon, Claire Getty, Gordon Getty’s niece, obtained a restraining order in California to prohibit Gordon Getty from signing sale documents related to the Getty Trust.

Jan. 5

As Pennzoil lawyers worked on the definitive purchase agreement, which was extraordinarily complex because it involved four entities (Pennzoil, Getty Oil, Getty Trust and Getty Museum), a banker advising Getty Oil secretly started discussions with other oil giants, including Texaco, Chevron and Shell Oil. In fact, Baker Botts flew additional lawyers from Houston to New York that night to help finish crafting the agreement.

Lawyers for Gordon Getty filed an affidavit in the California case from one of his investment bankers claiming under oath that the Pennzoil purchase was “a done deal” and that the Getty Oil board had approved the transaction.

Jan. 6

Just before or a little after midnight, Getty Oil bankers told Gordon Getty that Texaco was offering $125 per share. After a series of meetings between Texaco executives and Lipton for the museum, Gordon Getty for the trust and Getty Oil executives, the Getty Oil board of directors voted 15 to 1 to accept Texaco’s offer of $125 per share. Importantly, Texaco agreed to indemnify all Getty Oil executives and directors from litigation brought by Pennzoil.

During the trial, Pennzoil lawyers would argue that the demand that Texaco indemnify the Getty entities and executives was proof that both sides knew the deal with Pennzoil was binding.

Jan. 10

Pennzoil filed a declaratory action against Getty Oil and Texaco in Delaware Chancery Court seeking to block the Texaco deal from moving forward.

Feb. 6

A Delaware Chancery Court judge denied Pennzoil’s request for a TRO, but stated in his decision that Pennzoil was likely to prevail in its claim that it had a binding contract with Getty Oil.

“I am convinced that Pennzoil has demonstrated a likelihood that it will be able to establish … that a contract came into being,” the Delaware judge wrote.

Feb. 8

Pennzoil lawyers moved to dismiss their lawsuit in Delaware without prejudice, pointing out that Getty and Texaco had not yet filed their answers to the complaint. Multiple legal journals later called this “Texaco’s $10 billion legal boo-boo.”

Fifteen minutes after getting the Delaware case dismissed, Pennzoil filed its lawsuit against Texaco, alleging tortious interference in blocking Pennzoil’s acquisition of Getty Oil. The lawsuit demanded that their case be decided by a Texas jury and sought $7.5 billion in actual damages and $7.5 billion in punitive damages.

Pennzoil had its long-time outside counsel, Baker Botts, leading the charge.

“Hugh [Liedtke] told me that he wanted to seek damages in Texas and that he wanted me to work with Joe Jamail,” Terrell said. “Hugh told me that he wanted a jury trial in Texas, and he yelled at me to file it right away. The Texaco folks were laughing at our lawyers because we were filing in Texas,” Terrell said. “But we had Texaco served right after we filed in Harris County, and Texaco was screaming and yelling.”

At 79, Terrell is the sole surviving member of leadership for either party’s trial team. He said the 17 months between filing the lawsuit and the start of the trial were incredibly intense, with massive amounts of discovery and a blitz of legal maneuvers.

“I had four days off during the next 27 months, and that included the day I got married,” Terrell said.

Because Baker Botts was Pennzoil’s lead outside corporate counsel and handled both the merger negotiations and the litigation, the Houston-based firm had more than 100 different lawyers work on the matter at different stages.

“Firm leaders really put great lawyers in a position to do great work and succeed,” said Baker Botts partner John Porter.

Porter graduated from Baylor Law School on May 14, 1984, and the firm quickly put him to work on the case.

“I had not even taken the bar exam yet,” Porter said. “I can’t think of a better way to start a career.”

The decision to hire Jamail was entirely Liedtke’s.

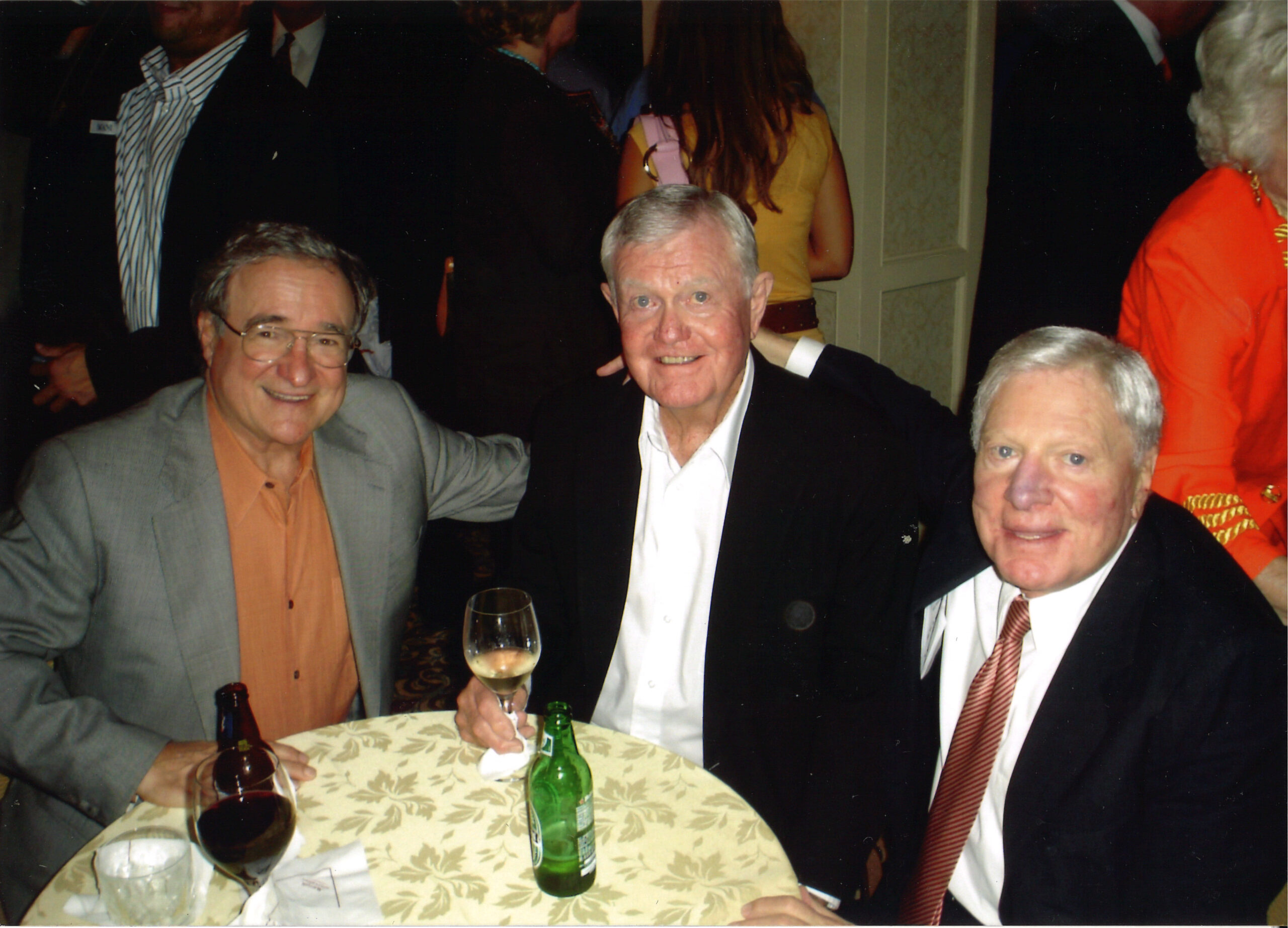

“This was not Joe’s normal kind of case at that time,” said Richard Mithoff, who was Jamail’s former law partner and close friend. “Joe and Liedtke were buddies, and Liedtke wanted Joe to help lead the trial. While Joe had never done this kind of case, Joe never lacked confidence.”

“Goddamn it, Mithoff,” Jamail told his friend after he agreed to join the legal team. “If I win this case, they should rename Texaco to Jamaco.”

Jamail had become infamous in Texas about a decade earlier when he represented the family of a man who was driving drunk and hit a tree that was growing in the median of a Houston street. The man’s widow asked the city to pay the funeral cost, but city officials just laughed at her. Jamail agreed to take the case and drove to the spot where the accident occurred.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes,” he told The Lawbook. “There was a tree growing in the middle of the damn street — a couple of them, in fact. I thought, ‘What the hell is a tree doing growing in the middle of the street.’ A street sign, I could understand but not a damn tree.”

Jamail sued the city of Houston, claiming that the trees were a public nuisance. He won at trial, of course, and the city paid for the man’s funeral, plus $6,000 for pain and suffering. The city also had to cut down the trees.

“I got calls for the next two years from these tree huggers cursing me for having the trees cut down,” he said.

Texaco hired its own high-profile trial lawyer to lead its defense.

Dick Miller was the former head of litigation at Baker Botts, but left the firm after more than three decades in 1983 to start his own litigation boutique, Miller, Bristow & Brown.

As a 17-year-old, Miller dropped out of high school to enlist in the U.S. Marines. In February 1945, he was one of 44 Marines in his platoon to go to battle on the Japanese island of Iwo Jima.

Miller reportedly convinced the dean at Harvard Law School to admit him as a student, even though he had never graduated from high school or college.

“Everybody agreed that Dick Miller was the best trial lawyer in this case,” said Yetter, who joined Baker Botts in September 1984 after graduating from Columbia Law School. “Miller was a take-no-prisoners trial lawyer. Very aggressive.”

“The fact that Miller was previously partners with our team at Baker Botts certainly heightened the intensity,” said Yetter, who started his own highly successful Houston litigation boutique, Yetter Coleman, in 1997.

Rob Walters, who was a rookie lawyer at Vinson & Elkins in 1985, was hired by a New York financial institution to sit in court during portions of the Pennzoil v. Texaco trial.

“I had the coolest assignment. My job was to sit in the back of the courtroom and take notes during certain testimony and then run to the pay phone at the end of the hallway and report what had happened,” said Walters, who is now a somewhat retired partner at Gibson Dunn in Dallas.

“I remember one of the jurors in the hallway saying, ‘Man, I tell you, I would hire Dick Miller if I ever got in trouble, because he’s the best lawyer, but Joe Jamail just had all the facts and a better case.’”

When Miller died in 2013, his obituary called him “the greatest Texas trial lawyer of his era.”

As the case worked its way toward trial, Miller filed a motion to have Harris County District Judge Anthony J.P. Farris, the judge assigned to try the case, recused because Jamail had months earlier contributed $10,000 to Judge Farris’ election campaign. A special judge from outside of Houston heard the argument but rejected the request.

Judge Farris set the first Monday following July 4 for the trial to begin.

“They used to say that the oil business was built upon a handshake,” Liedtke told The Wall Street Journal in an interview two weeks before the trial. “Should it now require handcuffs?”

July 8

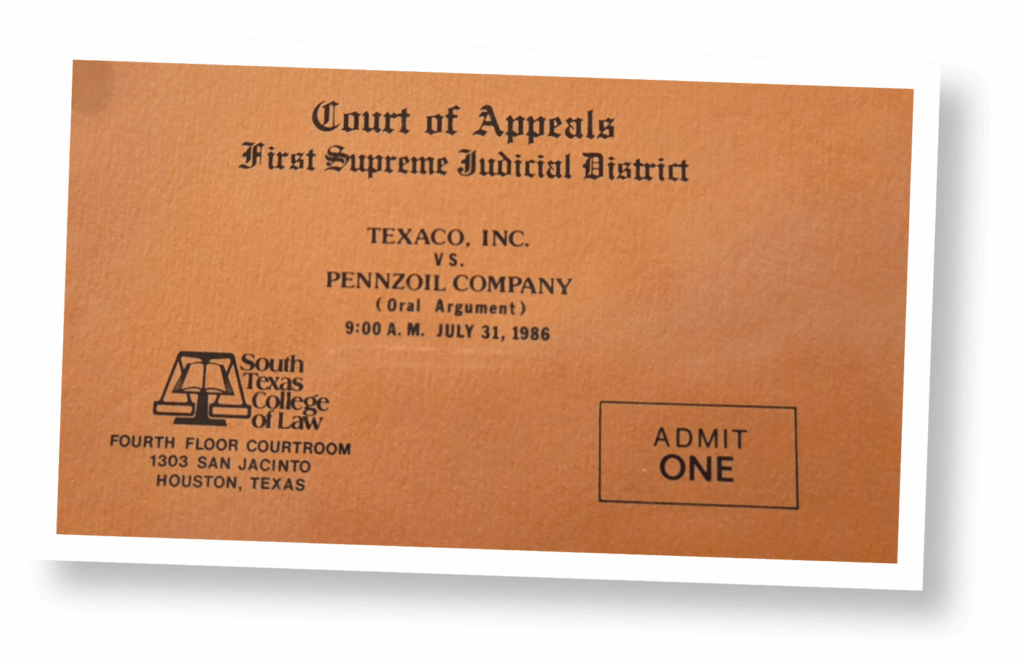

Texaco lawyers file an appeal seeking to disqualify Baker Botts from representing Pennzoil in the trial because one of its lawyers may be called as a witness. The Houston Court of Appeals denied the request.

July 10

The trial officially began that Tuesday with jury selection.

Jamail showed up for court most mornings in a chauffeur-driven Jaguar painted British racing green.

It took six days of voir dire before a panel of nine women and three men was selected to decide the facts. Four alternate jurors were also chosen.

Judge Farris told jurors that New York contract law would apply, as the negotiations took place in New York City, along with Delaware corporate law since both companies are incorporated in Wilmington.

In preparing for trial, the Pennzoil legal team split the duties evenly among Jamail, Terrell and fellow Baker Botts partner John Jeffers, who was assigned opening statements and presented the first few witnesses.

“Jeffers did the direct witnesses establishing that there was a binding agreement, and he handled the damages model,” Terrell said. “Joe really didn’t say much for the first two months of the trial. But his cross-examination of key witnesses was extraordinary — decisive.”

Baker Botts partner Bill Kroger, who was still in law school during the trial and appeal, said Jeffers was a brilliant lawyer who died of a brain tumor in 1989 at the age of 46.

“He was by far the least flamboyant lawyer in the courtroom during this trial,” he said.

July 17

Jeffers presented opening statements for Pennzoil. He told jurors that there was a “binding contract” between Texaco and Pennzoil.

“We say an agreement in principle is an agreement on all essential terms. And if you have that, you have a good faith duty to complete the transaction,” Jeffers told the jury.

But Miller, Texaco’s lead lawyer, responded that all Pennzoil and Getty Oil had was “a concept.”

“We’ve got a framework — nobody is bound to it. We’re going to see if it can work out,” Miller told jurors.

July 19

Kerr, Pennzoil’s president and a former Baker Botts partner, was the trial’s first witness. The plaintiffs used Kerr to introduce the Jan. 2 memorandum of agreement and the joint press release issued by Pennzoil and Getty Oil. Kerr testified that Pennzoil was willing to offer more to Getty Oil.

“I think most responsible businessmen would not feel that they were free to go out and abandon that deal,” Kerr told jurors. “The normal course of events would be negotiations, agreements in principle on the basic terms, and then work it out.”

Aug. 26

Pennzoil chairman Liedtke took the witness stand and told jurors that Pennzoil became interested in purchasing Getty Oil when he learned that there was turmoil between Gordon Getty and the Getty Oil executives.

“Somewhere in that mess, there was a business opportunity,” Liedtke testified.

Liedtke told jurors that Lipton, a founding partner of Wachtell Lipton and lawyer for the Getty Museum, warned Gordon Getty on Jan. 5 that if he did not agree to sell the Getty Trust’s shares to Texaco, the shares would be less valuable and that he would have no say regarding the company’s management.

“Obviously, [Lipton] didn’t go up there to pass time with good ol’ Gordo in the middle of the night,” Liedtke testified. “In my view, the trust was frightened into selling to Texaco.”

“Pennzoil has been permanently and irrevocably damaged” by the merger of Texaco and Getty Oil, he said.

Aug. 29

Pennzoil lawyers called retired Standard Oil Company executive Thomas Barrow as an expert in determining the amount of damages Pennzoil suffered because of Texaco’s alleged interference. Citing his four decades of experience, Barrow told jurors that Pennzoil lost between $6.5 billion and $8 billion.

While Texaco lawyers challenged Barrow’s estimates through cross-examination, they never presented alternative damage models.

“Miller didn’t like putting on defense damage models because it looks like you are admitting liability,” Terrell said.

Many legal experts over the years have said this was a critical error on the part of the defense team.

Sept. 19

Pennzoil lawyers rested their case. Texaco asked Judge Farris for a directed verdict to dismiss the case, which Judge Farris denied.

Oct. 21

Judge Farris, a former federal prosecutor, announced that he was stepping down as the trial judge due to illness.

Oct. 29

Retired San Antonio trial Judge Solomon Casseb was appointed to replace Judge Farris.

A Getty board member testified that the details announced in “the press release seem to go beyond what we agreed upon Jan. 3.”

Miller also called Getty Oil board member Lawrence Tisch, who was the co-chairman of Loews Corporation and was about to become the head of CBS, to testify. Tisch told jurors that there was no final contract.

On cross-examination, Tisch admitted that the night after the Getty Oil board voted to accept Pennzoil’s offer, he had champagne with Gordon Getty, toasting the agreement. But he said they were only toasting “the acceptance of a price that could lead to an agreement,” not a final agreement or contract.

Oct. 30

Getty Museum lawyer Lipton, under direct examination, said the museum was not bound by the agreement signed by Pennzoil and Getty Oil, and he denied that he pressured Gordon Getty to sell to Texaco.

Under cross-examination by Jamail, Lipton admitted that the museum’s president sat on the Getty Oil board of directors and was the director who made the motion that the board approve the Pennzoil offer on Jan. 3.

“Marty Lipton’s testimony was terrible for Texaco — he was not a good witness at all,” Terrell said.

In an interview after the verdict, Shannon, the jury member who wrote the book, said that Lipton “not only admitted he was a fast-talking double-dealer, he bragged about it.”

“By the time he left the stand, he had driven the last nail in Texaco’s coffin,” the juror said.

Nov. 6

Texaco General Counsel William Weitzel told jurors that his company would never have made an offer to buy Getty Oil if Getty had a valid contract with Pennzoil.

“If I ever had the slightest idea that there was a binding contract between Pennzoil and Getty, I would never have moved an inch,” he told jurors.

Nov. 14

The jury heard closing arguments. The judge gave each side about four hours to recap their case for the jury.

“There is an opportunity here to send a message which will preserve integrity in American business,” Jeffers told jurors. “If Texaco can get away with doing this in this courtroom, what they did to Pennzoil in the marketplace, then it can do it to someone else. It’s time for an accounting.”

Terrell argued that the indemnities Texaco provided the officials at Getty Oil, the trust and the museum were designed to let the Getty folks make extra money without being held accountable.

“This case is about arrogance, power and money,” Terrell told jurors. “Don’t let them get away with these indemnities.”

Miller countered that Pennzoil failed to prove its case and said that Kerr and Liedtke “stand to benefit several hundred million dollars personally” if Pennzoil won the case.

“Dick took all four and a half hours talking to the jury himself, and I think the jury was just exhausted by that point,” Terrell said.

Nov. 15

Day two of closing arguments focused on Jamail doing his rebuttal. Throughout the trial, he called the defendants “New York Texaco.” Texaco was founded in Beaumont, but moved its headquarters to White Plains, New York. He said Texaco was being led by New York bankers and New York lawyers. And he told jurors that those New York Texaco executives were greedy and had forgotten the importance of a Texas handshake agreement.

“This case is about people keeping their word and being honest,” Jamail told jurors during his rebuttal arguments. “My client honored their word. The other side did not.”

Nov. 19

Paul Yetter, then with Baker Botts, was at the courthouse a few hours before the jury returned with its verdict when he saw James Shannon, the juror who wrote the book.

“I was standing on the floor, I think it was the fourth floor of our courtroom was and looking out the window, looking down at the street,” Yetter recalled. “This is as the jury is deliberating, and coming back to lunch, and he gave me a big thumbs up, just like this [making the gesture]. I told my colleagues … I think we’re going to be okay in the verdict.”

According to Shannon’s book, the jury voted seven-to-five for Pennzoil in its vote that Friday on liability. On Monday, the vote was 10-2, favoring Pennzoil. By the end of the day, it was 12-0.

In his book, Shannon said the first vote on damages had six jurors ready to slap Texaco with the full $7.53 billion in punitives. Two jurors were opposed to awarding any punitive damages. Then, the panel reached a compromise.

After deliberating for more than nine hours over three days, the Harris County jury unanimously found that Texaco had intentionally and willfully interfered with the agreement between Pennzoil and Getty Oil. The jury awarded $7.53 billion in actual damages and $3 billion in punitive damages.

Each member of the jury was polled, and each confirmed that it was their verdict.

Jamail told the Houston Chronicle that the verdict sent a message to mergers and acquisition lawyers and bankers that “citizens of the U.S. demand that attention be paid to integrity, morality and honesty in business transactions.”

“If a small group of people who have anointed themselves to be the caretakers of American business don’t get this, then they are slow learners,” Jamail said. “It’s a clear warning that is going to sound all over America.”

Lawyers for Texaco told reporters that the company would appeal the verdict.

The Wall Street Journal, in an editorial, called the verdict “The Texas Common Law Massacre.”

Four decades later, Pennzoil v. Texaco still has lasting implications for transactional lawyers and for litigators.

“To this day, transactional lawyers have to make sure that they specifically indicate whether a binding agreement has been reached or just an unenforceable agreement-to-agree,” said Judge Edison. “Trial lawyers on the defense side must decide whether to offer an alternative theory of damages. And, in my view, the biggest takeaway from the Pennzoil case is that it really does matter where you try to lawsuit. The Harris County courthouse turned out to be the absolute best venue possible for Pennzoil. Had Texaco simply filed an answer in the Delaware litigation, the case would have proceeded there and the Pennzoil v. Texaco case might have been long forgotten.”

Writer’s note: In addition to more than 18 interviews, The Lawbook also relied on two law review articles for source information, including one by University of Tennessee Law Professor Robert Lloyd and the second written by University of Texas Law School Dean Mark Yudof and Baker Botts partner John Jeffers.

Related coverage

Coming later this week, The Lawbook looks at how Pennzoil v. Texaco continued to make news and law during its three years of appeals.