Many trial-centric CLEs set forth the traditional top 10 tips for a successful trial presentation. Examples include: Don’t ask a question to which you do not know the answer, be honest and ethical, tell a compelling story, make sure your witnesses are prepared, don’t fight with opposing counsel, etc.

These are worthy tips. But there are many other mistakes to avoid that stem from the evolution of juror behavior over the last 20 years — and especially in the five years since COVID.

I have handled more than 100 trials over 35 years. During that time, there has been a sea change in what is and is not effective. How do we know this? Because juries have told us.

Assuming there is no prohibition by the court, we contact our juries after each trial with questionnaires and phone interviews asking what they did or did not like, what was or was not persuasive and what we could have done better.

Uniform comments have emerged over the years, leading to gradual changes in how we try cases. We emphasize avoiding what juries do not like. These “dont’s” became even more pronounced post-COVID, as jurors are more suspicious of lawyers, are far more opinionated and are more likely to accept conspiracies and hidden motives.

Yet many lawyers continue to try cases using outdated strategies. Avoiding some of these old trial tactics could help you avoid losing.

So, here are the “other” top 10 trial mistakes.

1. ‘KISS’ (Keep It Simple, Stupid) Is … Stupid

We are told the average juror has a seventh-grade education and the way to try a case is to make it as simple as possible. This seems to have originated in the 1950s and is belied by hard data.

Years ago, we had to go to the library to get answers to obscure issues. Many people were deferential to anyone with a college degree. No more. Today, information on anything is a touch away on our phones.

A Houston Chronicle survey showed that nearly half of those who appeared for Harris County jury service have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Nearly two-thirds have at least a two-year associate’s degree. This is no different than any major metropolitan area. Most of the folks who honor a juror summons in larger cities today tend to be middle class and more educated.

Oversimplifying a case and talking down to jurors not only insults their intelligence, but many times they conclude that the lawyer is hiding something by failing to set forth details. Among the top three pet peeves of today’s jurors is a lawyer assuming they are simpletons.

We “talk up” to the jury and do not “talk down” to them. Yes, there may be one or two jurors who don’t have a high school education, but usually those folks are not the leaders. They follow the herd.

The key is to be organized and clear. I am not suggesting you overcomplicate the facts; but don’t fret if you have a highly complex issue. Explain the concept the way a great schoolteacher would.

I learned this the hard way more than 30 years ago when I tried a very complex oil and gas case with hundreds of exhibits. I felt we clearly had the better case, and I chose to present it at 40,000 feet. The opposing lawyer chose to stay at ground level. We were like two ships passing in the night. I felt certain the jury “was lost” in the detail. But John Zukowski was organized, clear and did not talk down to them. I thought I had won and was shocked when I was hit with the biggest loss of my young career.

The jurors told me afterwards that the other side presented “real evidence,” while our side ran from the evidence because we oversimplified everything. They understood his points because of how well organized he was. I learned a valuable lesson.

Use charts and clear examples, but don’t dumb it down. Our firm tries complex patent infringement cases all over the country involving cutting-edge tech issues. In every such trial, the jurors can follow and understand the issues because the focus is on clarity and organization instead of simplification.

2. Lather, Rinse, Repeat and Repeat Some More

A popular but mistaken school of thought says that if you say the same thing often enough, it will sink in better. The reality is juries HATE repetition. In this era of shortened attention spans, jurors tell us that repetition during trial is one of their other top three pet peeves. The more you say it, the more they don’t like it. And the less effective it is.

Many lawyers who have great evidence hammer it home repeatedly. They may think, “The jury may have missed it” or “Jurors aren’t that smart, and it needs to sink in” or perhaps “It won’t hurt to repeat it.” The reality is every time you repeat, you desensitize the jury to the impact of that evidence.

Think of the Rodney King beating video. It was a horrific display of police brutality. The prosecution played it countless times during the officers’ trial, and the result was a not guilty verdict. Jurors saw it so many times they became immune to the horror of it.

Most judges allow jurors to take notes. Every trial has one or two jurors who take copious notes. Trust the intelligence and memories of those jurors.

We had a high-profile defamation case years ago representing a small cleaning company against a big labor union. Our client’s president had recorded the head of the union telling him that he needed to come to the bargaining table because there were people in the union who wanted him killed. We did not mention that in opening, did not solicit that information from the president or even mention it in closing. That evidence came out one time – during the cross of the union head. It went off like a bomb. We never played it again, but after trial, it was all the jurors wanted to talk about. It was the largest defamation verdict ever against a labor union.

Remember, saying it or showing it more can result in less.

3. Show Passion Early

You have worked on the case for more than a year. During that time, you have seen your opposing counsel do some unscrupulous things and seem hostile at many hearings. You are convinced that you are the good guy and that the opposing lawyers are transparently bad. The jury, however, has seen none of that. They were thrown together with 11 other strangers and are deeply suspicious.

At the onset, jurors do not share your passion for the case. If you come out swinging, the jury will focus on your indignation and not the facts. It is a kiss of death if you begin the case by calling the opposing counsel a liar or not believable. Juries HATE that, and that type of attack will boomerang.

I am NOT saying to avoid indignation or passion. But never let your indignation rise above the level of the jury. Sometimes a little indignation will help you win but you should elevate the indignity only as the trial progresses.

Lay out the facts. And lay off the early overextended outrage.

4. Juries Make Up Their Minds After Opening, So Lay It All Out Early

Lawyers used to believe you should show your hand and all your “good stuff” during opening. The thinking was that jurors make up their mind before the first witness is called. Again, this is hand-me-down advice from the 1950s. This is not only wrong today, it ignores how people process information, especially in trial.

Real trial lawyers know a trial is like a dramatic play, because it involves unfolding arguments, suspense and the presentation of new evidence every day. Just as in a play, there are characters, conflicts and a narrative that builds toward a climax: the final verdict. Every streaming service offers dramas that unfold over many episodes with fresh surprises every week. We take our cues from those shows and try to make our part of the case better each day.

Jurors tell us they love how we add new information every day. Meanwhile, the other side keeps repeating the same things. We do not mind being a little behind after opening. Yes, it is very important to lay out the themes in opening and explain exactly what the jury will be deciding, but we intentionally hold back some of our best evidence so that we have something fresh on day two or day three.

We work hard to be fresh every day and provide a sense of momentum to the case, similar to a great TV series like The Sopranos or Breaking Bad. Those shows leave you with a cliffhanger. You must tune in to the next episode. We can even offer up a clue during opening like, “Just wait until you see what Mr. X said in a secret email to his board” and not show that email until Mr. X takes the stand.

You are trying to climb the mountain. Don’t start at the top of the mountain, because there is only one direction you can go from there.

5. ‘Objection! Misstates the Evidence!’

Yes, that silly objection is made all the time in our trials. So is, “Objection, that is not fair” or “Objection, that is not true” or my favorite, “Objection, form.” These objections do not exist under the rules of evidence. Yet lawyers make them all the time.

You are about to go in for surgery. Would you let the surgeon cut on you if she does not know how to use surgical tools? Of course not.

The trial lawyer’s tools are the rules of evidence. They are very powerful weapons. My impression is that 90 percent of trial lawyers do not know the evidence rules beyond rule 403.

Such examples as conditional admission of exhibits, the true extent of optional completeness, adoptive admissions as a response to the hearsay rule, how to properly seek a limiting instruction, when reputation evidence is admissible, the details around character evidence, how to properly impeach or the exceptions to exceptions to hearsay are foreign concepts to many lawyers in trial. When we encounter an opposing lawyer like this, we exploit their lack of knowledge of the rules and sharpen our knives — particularly when it comes to their key pieces of evidence.

A lawyer with complete mastery of the rules will almost always tie the other side in knots and may even change the outcome of the case, because tailored objections keep the other side from proving their case or raising a winning defense. I have lost count how many times an opposing lawyer was unable to impeach a witness with their deposition because they did not know how to lay the predicate. Sometimes this determined the trial’s outcome.

Judges tend to notice which lawyers know the rules and which ones do not. When a lawyer makes a nonexistent objection like “misstates the evidence” and is repeatedly overruled, jurors notice who knows what they are doing and who does not. And jurors and judges can lose patience.

Even after 100 trials, I painstakingly go through every rule (and subpart) before every trial and force myself to think about facts in which that rule would apply. I then think about objections and responses based on that rule. I always take younger lawyers with me to trial. They will earn the right to take witnesses at trial if I am convinced they know the rules backward and forward. I expect them to go through the same exercise as me and apply each subpart of every rule to some issue in that case. It is pure joy when I see one of our first-year lawyers apply a rule to a situation that we anticipated in advance and watch them navigate through that rule better than opposing counsel.

If you want to be a better trial lawyer, master the rules.

6. Emphasize Key Admissions You Get on Cross by Repeating Them

You are cross-examining a key witness, and you just obtained a beautiful admission that guts their case. My friend (and brilliant trial lawyer) Dan Cogdell says, “Once you get the kill shot, shut up and walk away.” This is how the jury will best remember this pivotal point.

But old-school theory is to hammer it in. Almost always, however, asking it again gives the witness an opportunity to fix the answer or muck it up. Then the lawyer will ask it again a third time trying to recapture the magic of the first answer, and the back and forth turns into a petty squabble and the point is lost. All jurors will remember is the witness and lawyer arguing. The kill shot is lost.

If you get a great admission, your most effective tool is silence. Stand in the well and let 30 seconds go by. Let the gravity of what the witness just said resonate.

Less can be more. There are 12 people listening. Juries don’t miss a thing. Trust the system, trust the jury. Be quiet and enjoy the kill shot, rather than messing with it and potentially allowing it to unravel.

7. Control the Witness on Cross-Examination and Force Them to Say Only Yes or No

The third thing juries hate most is an evasive witness. Evasive witness = zero credibility.

We are taught to maintain control over a witness during cross. That is usually good advice, but sometimes you need to let the witness run their mouths. When you ask a witness a simple yes or no question and they offer a long explanation that never answers yes or no, you may be losing the momentary battle, but you are winning the war. What should you do when that happens? Apologize to the witness and say, “Maybe I wasn’t clear, and I apologize. Let me ask it differently.” Ask a variant of the same question again. When that witness again does not answer yes or no and tries to “explain,” the jury and judge will get frustrated and conclude the answer is very bad for that witness. When you ask it a third time — and again the witness evades — the judge may blow her top and order the witness to answer. The best crosses sometimes are the ones where the witness will not answer any of the key questions.

You must pick your spots. Sometimes, you want to limit the witness to yes or no, but if you can turn that witness into being repeatedly evasive, you will score more points than if you obtained the admission the first time. This works best with a shady or dishonest witness.

8. Cut Off a Disgruntled Venire Person Who Could ‘Poison the Well’

The singular purpose of voir dire is to identify and strike bad potential jurors. The purpose is not to convince the panel your case is just or that you are a nice person. Maybe 60 strangers are seated next to each other and are reluctant to raise their hand to offer their opinion on a topic in the case (e.g., punitive damages). What happens when you are representing a plaintiff and one venire member says, “There are too many lawsuits and lawyers like you who file frivolous cases in order to make money”? Now what do you do? Conventional wisdom is to avoid asking follow-up questions and saying you will bring that person to the bench with follow-up questions later, believing this venire member will “poison the well” by influencing other jurors if allowed to continue. How naïve.

What is unassailable these days is that people who follow social media (most of us) live in an echo chamber. Those algorithms are designed to feed you news and opinions that align with your world view. More people have strong views about things today than 10 years ago. The panelists looking at you almost certainly have strong views about some of the things you are asking. If you do not uncover that view, that person who is strongly biased against you could end up on the jury, and there is almost nothing you can do during trial to turn them around. You will lose not based on the facts or law, but because you did not strike them.

Instead of waiting until the end of voir dire to bring that venire member to the bench, get them over the line for cause and ask row by row who agrees with that potential juror. The idea that a negative comment from a stranger will influence the rest of the panel (who have their own strong views) is contrary to common sense. The nastier the comments about your side during jury selection, the better! It makes it easier to strike for cause.

My rule of thumb for voir dire is that if you do not strike at least eight people for cause during jury selection, you have failed. The only way to achieve this is to get bias out in the open and see if others on the panel agree.

It’s a myth that folks start with neutral minds. Use the chance to cull your bad apples in public rather than waiting to see if they’ll go against you in the jury room.

9. Use PowerPoint to Describe All the Key Facts

Visuals at trial can be a powerful supplement to your presentation, but they should supplement the message and not act as a substitute. They should not compete for attention with what the lawyer is saying.

Many lawyers use tools like PowerPoint to display their entire outline, opening and closing. The more you display on a PowerPoint, the less effective it is.

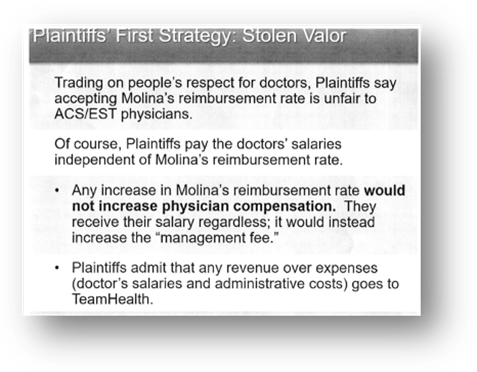

Here is an example of one slide from a defense lawyer’s 60-page PowerPoint used in an opening statement in a trial several years ago. Almost every page of the slide deck was like this:

While displaying endless paragraphs of his entire defense through the PowerPoint, the lawyer read his opening, which did not align with what was on the screen. The result was mass confusion between trying to listen and trying to read. Many jurors tuned out after a few minutes. Not surprisingly, the jury returned a huge plaintiff’s verdict.

Words on a PowerPoint are like hemorrhoids — you want as few as possible.

Here are our guidelines for PowerPoint:

- Five words per line

- Three lines maximum

- Large font

- One uniform font

- Do not capitalize every letter

- One idea per image

10. Mock Trials Will Help You Win

Clients and many lawyers in large cases believe conducting a mock trial will help them identify winning points for trial. Few lawyers, however, have enough trial experience to try a case properly. Consultants have proliferated as a result. These all-day exercises now cost $50,000 to $200,000 (or more). However, the cost is not the biggest problem. The problem is that mock trials can do more harm than good. Why?

- The inability to strike biased jurors. The folks who showed up did so voluntarily because they want to get paid and not because they have to show up. Mock trial jury deliberations are dominated by the craziest, most opinionated, overbearing jurors. In a real trial, that person would never end up on the jury. Those forceful personalities can distort significantly what the message should be.

- Trials take days, weeks or months and have peaks and valleys. Advantages bounce from one side to the other. Mock trials are condensed to a few hours. There is no way to capture the ebb and flow of a real trial.

- Mock trials play with Monopoly money, and that creates a juror bias toward the plaintiff. Despite what consultants say, the mock jurors know the money is not real.

- The jury charge is one of the biggest variables in a trial outcome. That charge is not decided until the end of trial. Mock trials do not utilize a full final jury charge, because they can’t.

- Witness credibility is an even bigger variable at trial. This is irrelevant during a mock trial, because at most they will get a 20-minute video deposition clip of one or two witnesses. And many mock trials do not have video clips of any witnesses.

- There is no real judge. Jurors look to the judge for nonverbal cues. How is the judge reacting to the lawyer who objects every five minutes? Did the judge admonish the witness for being evasive? None of this is present at a mock trial.

- The sample size is too small to be statistically significant.

- Lawyers can’t help themselves. They try and “win” the mock trial and often step way out on the pier. A real jury acts as a check against the unbridled enthusiasm of a mock trial lawyer.

On the other hand, focus groups and marketing surveys can help with unique discrete issues, arguments or themes. But I believe mock trials are essentially worthless.

* * *

These suggestions are my own and come from my experience. Every trial lawyer is wired differently. Some of these points may apply to you, and some may not. The most important thing you can do is try more cases so you can figure out what works best for you. Taking an occasional no-fee case and pushing it to trial will give you the experience to navigate the hundreds of variables that are at play during trial.

John Zavitsanos is the managing partner and co-founder of AZA. He is a highly regarded trial lawyer who loves trying cases and loves winning. Rated Band 1 in both trials and commercial litigation by Chambers, he is the primary author of O’Connor’s Texas Rules * Civil Trials 2018-2025.