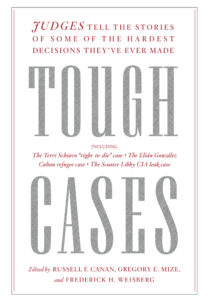

Editor’s Note: In Tough Cases, a newly published collection of essays, judges from across the country recollect their experiences presiding over courtroom conflicts – conflicts that generated intense legal debate, great public attention or profound personal anguish. The book so impressed us that we asked one of its editors, Judge Gregory Mize, to highlight for our readers some of the cases it details. As you’ll see, their stories provide not only a stroll through some of the most significant jurisprudence in recent decades, but also a reminder of the vital role played by extraordinary human beings whose everyday job it is to preserve the Rule of Law.

As any judge who has served on a trial court can attest, there are many assignments where the cases come at you so hard and fast that there is barely time to step into the box and take your stance before the next one comes zooming in. And that is true of the “easy” cases. This book is not about those. It’s about the rare times in a judicial career where the judge has to wrestle with a problem so complex, or so emotionally draining, as to test the fortitude and impartiality of even the most competent and experienced jurists.

In busy trial courts, these cases can appear in the garb of criminal, civil, probate, or family cases. Often the judge is unable to find any guiding legal precedent and is forced to navigate uncharted waters in search of the “just” result. Sometimes controlling legal precedent exists but following it will lead to an unjust result.

And then there are cases where the judge has very wide discretion to apply a vague legal standard, like “the best interest of the child” in contested child custody proceedings or finding the “right sentence” in a criminal case, where the statutory range might run from no prison time at all to life in prison.

Some cases are hard not only because of the subject matter, but also because they capture the attention of the entire community and become highly politicized. This can be especially challenging for elected judges, who know that whatever decision they make may become the fodder for an opposition campaign when they next stand for election and may cost them their judgeship. These political realities do not lessen the judge’s duty to decide each case in accordance with the facts and the rule of law, by reference to neutral principles. Community sentiment they can make the exercise of that duty more agonizing, knowing that the decision is likely to be unpopular with at least one large segment of the population.

Judge Robert Alsdorf of Washington State writes of one such case in “Can an Elected Judge Overrule Nearly a Million Voters and Survive.” His high stakes ruling could have cost him his judgeship but, when he explained his decision in a detailed opinion, the public accepted the ruling and came away with a better understanding of the rule of law. In “Elian,” Judge Jennifer Bailey of Florida explains her handling of the highly publicized Elian González contested custody case, describing how she stood up to the pressure from outside forces attempting to influence her decision, including the Congress and President of the United States. A third chapter in the same category is federal Judge Reggie Walton’s description in “United States v. I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby” of the trial of Vice President’s Richard Cheney’s Chief of staff in an obstruction of justice case that was closely watched by the White House and much of the rest of the country. A final example in this category is the story of “Terri’s Judge” told by Florida Judge George Greer, who found himself randomly assigned as the judge called upon to decide, between competing interests and under the glare of national attention, whether Terri Schiavo — comatose and in a persistent vegetative state — should continue to live or be allowed to die.

The other selections, less well known, chronicle struggles to find justice within the confines of the law, when the path is either unmarked, or is clearly marked, but pointing in the wrong direction. The authors, each with years of experience on the bench, tell the stories of how they dealt with the cases they found to be among their most challenging. In my case story entitled “Brave Jenny,” I presided over a very emotional child neglect matter, where I was compelled to remove a young girl from her mother for years. The mother’s lack of insight into her mental illness and presented a continuing danger to the child that stymied persistent efforts to reunite them. In another child custody case, Judge Gail Chang Bohr of Minnesota, in “A Judge’s Hidden Struggle: Overcoming Judicial Culture,” had to choose between accepting the stipulated agreement of both parents to share custody of their child, which in most cases would be a no brainer, or to reject the agreement and award custody to a third party based largely on her instinct, later borne out by events, that neither parent had the capacity to protect the child’s best interests.

Judge Russell F. Canan of Washington, D.C. writes in “Rough Justice” of a criminal case in which he struggled with following the law when it appeared that a jury in a criminal case was about to return a verdict that would require him to impose a harsh mandatory sentence, which the judge considered manifestly unjust under the facts of the case. In “Crazy or Cruel: The trial of an Unexplained Filicide,” Judge Frederick Weisberg, also from Washington, describes his experience presiding in the trial of a mother accused of murdering her four daughters and living alone with their decaying remains for many months until her landlord discovered them in the course of evicting her for nonpayment of rent. The trial put the judge squarely at the intersection of law and psychiatry, when in a highly unusual turn of affairs the defense attorneys challenged their client’s mental competence to refuse to present a defense of not guilty by reason of insanity.

Two chapters take the reader completely outside the traditions of American jurisprudence. In “Walking with my Ancestors: Tribal Justice for Salmon Running,” Judge Allie Greenleaf Maldonado, a tribal judge for the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians in Michigan describes how she took a risk with a seemingly incorrigible defendant in a felony drug distribution case and, against the odds, managed to shift the focus from what would normally be an almost certain conviction and prison sentence to a more healing approach, which enabled the defendant to see the path to sobriety and a productive future. Judge Edward Wilson takes us not to his home state of Minnesota, but to Kosovo where he was assigned as an international judge for a United Nations mission to preside over the prosecution of several members of a notorious organized crime syndicate charged with a series of violent jewelry store robberies. His story, “Building Justice in Kosovo,” presents a lesson in the application of the presumption of innocence and the reasonable doubt standard in the context of a society that has not fully embraced those principles or the rule of law.

In “A Quiet Grief,” Judge Lizbeth Gonzalez of New York tells the sad story of one that got away. While she was trying to help the parties work out their differences in a very contentious landlord and tenant dispute, tragedy struck. Finally, the one inexperienced judge among the contributing authors, Judge Michelle Ahnn, in “Every Case is a Tough Case for a New Judge,” writes of her personal transition from an experienced public defender in California to a neophyte judge presiding over a criminal misdemeanor calendar. As she describes it, every case was a hard case requiring her to distance herself from her former client-based advocacy and to decide each case impartially based solely on neutral principles.

Given that few judges have publicly shared the thought processes behind their decision making, Tough Cases can be enlightening for John Q citizen as well as trial advocates who want insight into the people judging their work. These true stories demystify judicial decision making, especially at a moment in American history where there is much focus on the judicial branch. They give a ringside seat to folks who may otherwise assume from afar that judges can simply do whatever they want. For those who think the system is unfair and fails by a wide margin to “do equal justice to the poor and to the rich,” these up-close stories should help such skeptics appreciate the complexity of the job and, at least in some cases, the agony in its execution. Readers summoned serve as judges of the facts in a jury trial may be inspired to embrace jury service as a desirable, important calling. For jurists, the book can be instructional for those who are new to the bench and, for veteran judges, it may inspire more stories to be written.

Interested readers can order the book here.