Editor’s Note: This work was originally published in the Texas Supreme Court Historical Society’s Journal, and is being reprinted here with permission.

“I Don’t Mind Trouble but I do believe in Fair Play and Justice. I feel I’m being taken in this case and I will tell people about it unless the trial is fair.”

— Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson1

Decades before Fort Hood (now Fort Cavazos),2 a Texas U.S. Army base, made national civilian news over the ever-present dangers and sexual misconduct-related injustices that too often await military service women — like Vanessa Guillen who was sexually harassed and murdered there in 2020— it was the site of another type of injustice: racial discrimination against its Black servicemembers. Too often in the 1940s, racial discrimination, both on and off U.S. military bases, was so heinous it ended in tragedy. In one notable instance, it would lead to the court martial trial of Major League Baseball’s (“MLB”) future pioneer and legend: Jackie Robinson.

Since during Jack “Jackie” R. Robinson’s military service, U.S. Vice President Harry Truman had not yet been appointed U.S. President3 and, thus, had not yet signed his 1948 Executive Order 9981 integrating the U.S. Military forces, young Robinson, a Californian, experienced first-hand the unjust impact of discrimination in a segregated U.S. Armed Forces.

Given the principled, deeply religious man Robinson had become and the harsh (sometimes fatal) realities that awaited such Black men in the Jim Crow South, where Robinson would be stationed, Robinson’s military service set him on a dangerous collision course with the South’s social norms. The course would culminate with The United States v. 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson, 0-10315861, Calvary, Company C, 758th Tank Battalion court martial trial. To better understand what led to the trial, we must briefly look back at Robinson’s integrated past.

Robinson’s Pre-Military Integrated Past & Close Call

Years before Robinson integrated the MLB, Robinson helped to integrate the University of California, Los Angeles (“UCLA”), where his athletic prowess landed him much notoriety and resulted in him becoming the first UCLA student to ever letter in four sports in the same season.4 Robinson left college in pursuit of future athletic glory or, absent professional sport opportunities for Blacks, to at least become an athletic director who trained other athletes. Robinson got his shot when he secured a National Youth Administration (“NYA”) job as an assistant athletic director over White athletes age 16-18.5

His athletic director dream came to an abrupt halt, however, at the start of World War II when the U.S. shut down the NYA programs nationwide.6 Resilient, Robinson pivoted and secured a spot on the Honolulu Bears, Hawaii’s integrated semi-professional football team.7

Just prior to the U.S. entering World War II, Robinson wrapped up his first season with the Honolulu Bears. Post season, Robinson headed home to California on a ship he boarded on December 5, 1941, a mere two days before Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.8 The U.S. military draft soon followed and marked the first time Black Americans were inducted on a large scale.9 On April 3, 1942, Robinson reported for military duty at the Los Angeles Induction Center.10 He joined millions of other draftees from both north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line.11

WWII, Robinson & the Segregated U.S. Military

In May of 1942, the U.S. Army sent Robinson to Fort Riley, Kansas for basic training where he was assigned to the calvary.12 Though never a member of the confederacy, segregation was nevertheless present in Kansas in a way Robinson had not previously experienced.

At Fort Riley, Robinson tried out for, but, due to his race, was barred from playing on the White-only baseball team.13 Undeterred by this, Robinson aspired to become a combat military officer, though at the time, Black servicemen were typically assigned almost exclusively to the non-combat service and supply units of the Army. Robinson, nevertheless, took and passed all the requisite tests to gain admission to Officer Candidate School (“OCS”).

Unlike his White counterparts, however, who were admitted to OCS soon after passing, Robinson and the handful of other Black soldiers who had passed admissions tests were not allowed to start OCS. For months they could get no real answers or reason for not being accepted into OCS despite being qualified and meeting the admission criteria.

Shortly after being transferred to Fort Riley and learning of the situation, famed boxer Joe Louis, who regularly donated large sums of money to the military, contacted some powerful government officials.14

Soon after, the Fort Riley command was subjected to enough heat from Washington, D.C., that Robinson and several other Black servicemen suddenly found themselves being welcomed to OCS to begin their thirteen weeks of training. Their Nov. 1st OCS admission marked the first time in U.S. Army history that OCS was integrated. Even so, it would still be some time before army rules would fully catch up to the OCS integration milestone. As they stood, army rules continued to forbid any Black officer from outranking a White officer in the same unit.

By Jan. 28, 1943, Robinson was finally made a second lieutenant in the calvary of the U.S. Army. Later that year, Robinson was appointed to serve as a morale officer of his company. As its name suggests, as morale officer, Robinson was in charge of taking steps to keep the Black soldiers morale up. Robinson strove to achieve this not just through organizing sports games but also by actively working to gain small victories against segregation for Black soldiers who were subjected to unfair treatment and conditions because of their race. For example, after a heated exchange with the base’s provost marshal about how “White” seats often went unused at the post exchange while Black soldiers had to wait long periods of time for the few seats assigned to them, Robinson succeeded in securing additional seats for Black servicemembers.

After this, Robinson and his fellow Black officers and soldiers waited to see whether Blacks would finally be allowed to fight in combat or continue to be relegated to the service units. Finally, the answer was made painfully clear: after two years of combat training, the Black 2nd Cavalry Division was converted into a service unit. This did not help morale. Understandably then, in August of 1943 when Robinson was asked to join the army’s football team, Robinson was reluctant but eventually relented and accepted the invite. However, Robinson’s 1943 military football career was short lived. The season starting game against the University of Missouri was intentionally played without Robinson, its only Black player, because Missouri refused to play against a team with a Black player. Rather than stand with Robinson or at least inform him of this, the military suddenly arranged for Robinson to be granted a two-week leave that strategically meant he would miss that first game.

When Robinson learned of the true reason for his leave, he resigned from the football team. He was simply unwilling to commit to playing for a team that was not equally committed to insisting he play over the objections, threats, and ultimatums of blatant racists and staunch segregationists. Arguably, this same resolve is, no doubt, what would later help forge the strong bond between Robinson and the Dodgers that made the duo a formidable force in the MLB.

In response to his resignation, the Colonel in charge of the football team told Robinson that he could order Robinson to play anyway. Robinson strategically replied that the Colonel would not want Robinson playing knowing his heart was not in it. Robinson’s reply likely did not earn him any friends among the superior officers there but it, nonetheless, was effective, because he was not ordered to play football.

In December of that same year, however, special orders were issued to transfer Robinson along with others south to Texas.15 In a Dec. 9, 1943, special order, Robinson was reassigned to the Second Calvary Division of Fort Clark, Texas, military base. Soon thereafter, however, the Fort Clark base would cease calvary training and eventually be ordered closed.16 Naturally then, subsequent successive transfer and reassignment orders for Robinson and others followed.

By Jan. 4, 1944, a Special Extract Order issued for Robinson and one other officer to report to the Brooke General Hospital at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, “for observation and treatment.”17 And “upon release from [the] hospital [they] w[ere to] p[resent for a] new assignment” based, no doubt, on the medical board’s determination of each man’s medical fitness to serve.18

In its Jan. 28, 1944, decision regarding Robinson, the Board wrote that, due to large bone chips in Robinson’s ankle, that was first broken playing college football, it “is of the opinion that this officer is physically disqualified for general military service, but is qualified for limited service. He is not qualified for over-seas duty at this time. The Board recommends: That he be discharged from the hospital for temporary limited service. … and that on or about 28 July 1944 he be reexamined with a view to determining his physical fitness.” The Board went on to outline Robinson’s restricted duties.

Robinson in the Jim Crow South

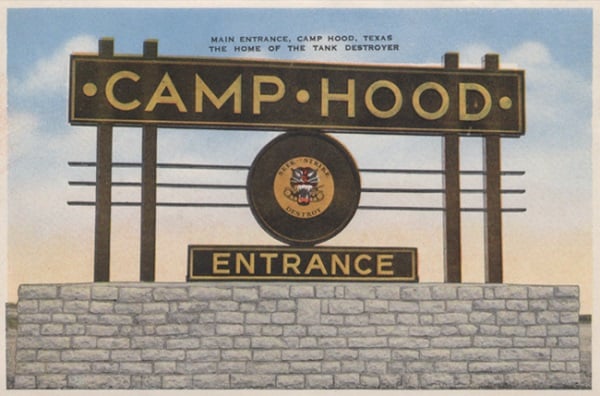

Eventually a more trying fate was thrust upon Robinson when special orders issued around April 13, 1944, informing him and other Black officers that they would finally get their chance to engage in combat overseas as newly attached members of the 761st Tank Battalion.19 However, to prepare they would be transferred to the 761st Tank Battalion’s headquarters located down south at the present-day Fort Cavazos, Texas, military base.20 At the time called Camp Hood, the base was named after Confederate General John Bell Hood who commanded a brigade of Texans against the Union.21

Camp Hood was the U.S.’s direct response to the German blitzkrieg. It was built to train U.S. military service men on anti-tank technology.22 Vast and new, Camp Hood was situated deep in the heart of Texas where Jim Crow laws reigned supreme.23

That Texas was once a part of the Confederate South was evident in the visible vestiges of the Confederacy that were ever visible there. Black servicemen recalled that both Camp Hood and the central Texas small towns that surrounded it were so thoroughly segregated that separate out houses existed for Whites, Blacks (“colored”), and Mexicans even on federal property.24 A friend of the Secretary of War’s civilian aide, Truman Gibson, opined a year prior that Camp Hood was “one of the worst situations in the whole AUS [Army of the United States]” as “[t]here is hostility between [military police and Black personnel] and segregation on interstate buses operating on the post, and segregation in the post facilities and theaters.”25

It was into this thoroughly segregated way of life that Second Lieutenant Robinson, who had already garnered an impressive resume of integration milestones — that included: (1) helping to integrate UCLA and the army’s OCS; (2) playing on the integrated Honolulu Bears’ semi-pro football team; and (3) using his morale officer appointment to win small victories for Blacks at Fort Riley — suddenly found himself. Robinson quickly learned that, to most Whites at Fort Hood, his Second Lieutenant officer rank was not the least bit important and so was deliberately disregarded or ignored.26

In stark contrast to this new reality, stood Lieutenant Colonel Paul L. Bates, a fellow Californian and the White commander of the 761st Tank Battalion, Company B to which Robinson was attached. Bates helped the Black men under him channel their indignation against racism “into a desire to succeed as no black outfit had succeeded before.”27 Bates noticed how, at Fort Hood, Robinson not only succeeded in leading his assigned platoon but also organized and used sports to boost their morale.

Thus, Bates asked Robinson to consider serving overseas with the battalion as its morale officer. Likely due to Bates’ shown commitment to fair treatment of Black servicemembers, Robinson was willing to serve overseas under Bates, even if it meant he would have to risk doing what he had previously been medically restricted from doing.28

Consequently, to serve, Robinson would not only have to be medically cleared for physical duty overseas, but would also have to sign a waiver releasing the Army from any financial claim or benefit if, as a result of Robinson’s overseas service, he reinjured his ankle. This meant Robinson would have to travel to the Army’s McCloskey General Hospital (“McCloskey Hospital”) to undergo another thorough examination to determine if he was physically qualified for overseas service and what type of duty, if any, he could perform. McClosky Hospital was located off base in the nearby small town of Temple, Texas.

To get there, Robinson would have to travel by government issued transport or public bus. At many southern training camps, like Camp Hood, it was not uncommon for the federal contracts for transporting soldiers both on and off the military base to be held by local civilian bus lines.29 Those bus lines often adhered to local, not federal, race laws, policies and practices. They also employed civilian bus drivers determined to enforce southern race protocols and eager to teach blunt lessons to uppity Black soldiers who wrongly assumed their military status exempted them from the south’s strict segregation of the races.30

On or about June 21, 1944, government motor transportation was arranged for Robinson’s travel to McCloskey Hospital to start the re-examination.31 Based on the initial results, the hospital’s Disposition Board concluded that Robinson’s condition remained “Unchanged.” And though Robinson was “still unfit for general duty” due to the bone chips in his ankle, Robinson was “fit for limited military service” and “overseas duty.”32 The board recommended that the Army Retiring Board reassign Robinson to permanent limited military service.33

The Bus Ride

On July 6, 1944, around 11 p.m., Robinson boarded a Camp Hood bus that was run by civilian owned Southwestern Bus Company to begin his return trip back to McCloskey Hospital.34 As he started walking towards the back of the bus, Robinson saw Virginia Jones, the wife of his friend First Lieutenant Gordon H. Jones Jr., sitting in the middle of the bus and sat down next to her. According to Mrs. Jones’ statement she “sat in the fourth seat from the rear of the bus, which I have always considered the rear of the bus.”

Though there is no general consensus on exactly what happened after this, after driving about 5 to 6 blocks, Milton Renegar, the White civilian bus driver turned and either ordered or, as implied from Renegar’s sworn statement, nicely asked, Robinson to move to the back of the bus.35 Initially, Robinson did not respond to Renegar as he figured that, since Renegar never asked Mrs. Jones to move to the back of the bus, Renegar’s order probably stemmed from him resenting Robinson for talking with Mrs. Jones whom Renegar likely mistakenly assumed to be White. Renegar, however, would later refer to Mrs. Jones in his statement as the “colored girl” who sat down “about middle ways of the bus.”36 When Renegar repeated his order, Robinson refused. Renegar threatened that if Robinson did not comply, he’d make trouble for Robinson when he made it to the station.

“… if he wanted to make trouble for me that was up to him.”

— Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson

Fully aware that the month prior, the Army had announced a new policy forbidding segregation on its military buses after a White bus driver in Durham, N.C., had killed a Black soldier, Robinson still refused to move. Instead, Robinson told Renegar “that if he wanted to make trouble for me that was up to him.”37

Exchanges between Robinson and the driver became heated. When the bus reached Camp Hood’s crowded central bus station, Robinson recalled a different passenger, Mrs. Elizabeth Poitevint telling him she is “going to prefer [i.e., press] charges against me.” To this, Robinson replied: “That’s all right, too, I don’t care if she prefers charges against me.”38

As Robinson prepared to get off the bus at the station, the bus driver asked Robinson for his military ID, but Robinson refused. Then Mrs. Poitevint, confronted Robinson. Nearly all the White witnesses said Robinson replied by threatening Mrs. Poitevint to “stop fucking with him.” Only Mrs. Ruby Johnson, who notably was Mrs. Poitevint’s friend who had been sitting with Mrs. Poitevint on the bus, did not.

According to Mrs. Johnson, Mrs. Poitevint walked over and shook her finger in Robinson’s face telling him she intended to report him to the authorities. Mrs. Johnson recalls Robinson responding by telling Mrs. Poitevint to “go away and leave him alone.”39

Later, Mrs. Ruby Johnson’s would be the sole White witness’ court martial trial testimony that seemed to corroborate Robinson’s account of what happened that day.

Robinson admitted using profanity but denied using profanity towards Mrs. Poitevint. Apparently, at some point after the driver told the civilian Southwestern Bus Company dispatcher, Bevlie “Pinky” Younger, to call the military police (“MP”),40 the driver, according to Robinson’s statement, then said, “this nigger is making trouble.”41

The driver then proceeded to start trying to get the other men present up in arms, after Robinson replied to the driver’s racial slur for the driver to “stop fuckin with me.”42 When the MPs arrived at the bus station, MP Corporal George A. Elwood asked the civilian bus dispatcher Younger “what the trouble was” to which Younger replied within earshot of Robinson “the trouble was with a nigger Lieutenant.”43

According to Younger, Robinson “resented being call so” and told Elwood in the presence of “100 to 200 ladies and other passengers on the buses” that “No God-damned sorry son-of-a bitch could call him a nigger and get away with it.”44

The MPs, who were all outranked by Lieutenant Robinson, asked if he would go with them to the MP station to straighten things out. Robinson agreed. At the MP station, inside the MP Guard room, the Assistant Provost Marshal Captain Gerald M. Bear commenced to taking statements from all the White civilians and servicemembers involved.

“I had never had a drink in my life.”

— Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson

Robinson was present and immediately observed how Bear did not recognize Robinson by his officer rank. Robinson recalled that instead Bear made him stand while asking the lower ranking White private Mucklerath to sit down. Bear made no mention of this in his statement.

According to Bear and others, Robinson kept interrupting Bear as well as the witnesses while they were trying to give their statements. Bear recalled telling Robinson to leave the MP Guard Room and ordering him to remain “at ease” and in the receiving room.

The only thing that separated the MP Guard Room from the receiving room was a swinging door. Robinson went out the swinging door into the receiving room but allegedly did not stay there. Instead, Robinson kept defying Bear’s orders and returning to the swinging door to interrupt.

Bear finally permitted Robinson to rejoin them in the MP Guard Room to give his account of what happened. Robinson disputes the account of his statement that was taken by Bear’s stenographer, a civilian White woman, because Robinson felt she was hostile towards him and noted how Bear allowed her to keep interrupting Robinson.

According to Robinson she asked him questions like: “Don’t you know you’ve got no right sitting up there in the White part of the bus?” and snapped that his “replies made no sense.”45 Robinson rightfully felt this civilian stenographer was not the proper person to question him. Nevertheless, Bear allowed this to continue until Robinson sharply replied to her that if she let him finish his sentence and quit interrupting, maybe his replies would make sense.46 According to Robinson, Bear defended that Robinson was an “uppity nigger” who “had no right to speak to a lady in that manner.”47

Robinson Framed, Charged, & Arrested

After taking Robinson’s statement, Bear had the MPs drive Robinson back to the hospital. Once there, a White doctor warned Robinson that the hospital had received a report that the MPs would be dropping off a drunk Black Lieutenant who had been trying to start a riot.48

After Robinson replied, “I had never had a drink in my life,” that doctor advised Robinson to take a blood alcohol test to disprove this narrative.49

The test results showed Robinson had not been drinking.50 The same doctor informed Colonel Bates of the events.51 When Colonel Bates looked into it, he soon learned of Bear’s intent to frame Robinson in an effort to have him court martialed. Bates refused to endorse the charges against Robinson.52

Soon thereafter, Robinson was transferred to the 758th Light Tank Battalion.53 Though recollections differ on the timing of when Robinson’s transfer was initiated (i.e., whether before or after the bus incident and Colonel Bates subsequent refusal to sign the charges), one thing is clear: Bear was undeterred by Bates refusal to sign and simply waited for Robinson’s transfer to the 758th Light Tank Battalion where a more compliant commander would, and did, quickly sign orders to prosecute Robinson on or about July 24, 1944.

That same day, the MPs arrested Robinson. With these signed orders, Robinson would be made to appear before the military’s highest level trial court reserved for trying service members for the most serious of crimes.

Robinson was rightfully concerned about being wrongly convicted for allegedly violating unjust laws and social norms that he technically never broke. After all, Mrs. Jones, his friend’s wife and fellow passenger, was, in fact, Black not White (a fact Renegar likely learned of ahead of giving his statement) and though Robinson had refused to go to the very back of the bus at Reneger’s demand, he had done so while they were still on the federal military base subject to federal laws, orders, and policies that prohibited, at least in writing, segregation in transportation.

Robinson’s Pre-Trial Quest for Help & Fairness

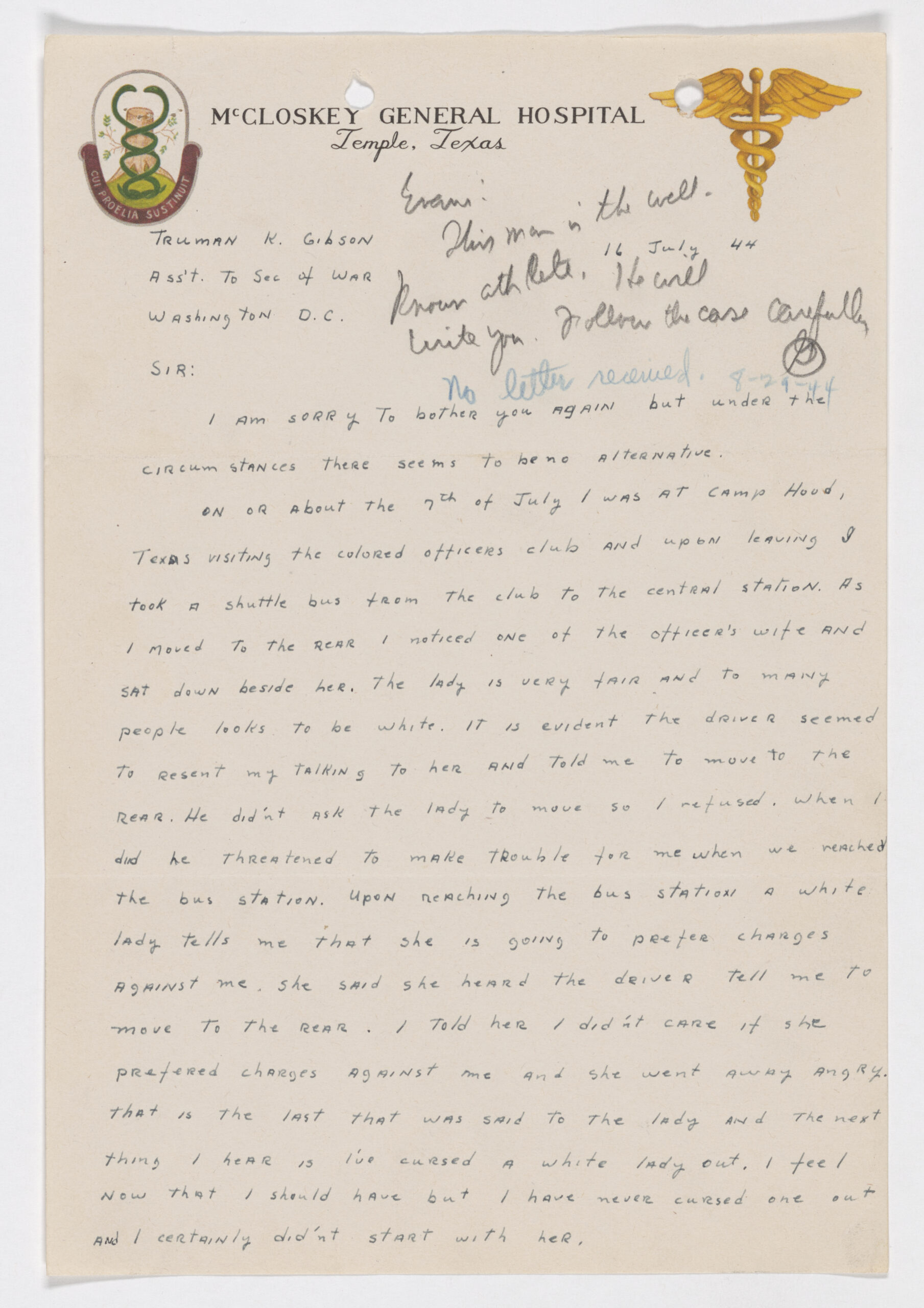

Unwilling to sit idlily by waiting to be framed, Robinson tried to get out ahead of the situation by appealing to Truman Gibson for guidance in a handwritten letter Robinson penned and dated July 16, 1944, (just nine days after the bus incident) on McClosky Hospital letterhead. Eager to counter any inconsistencies recorded by the hostile stenographer with his own statement, Robinson opened his letter with an explanation of what transpired.54

Robinson explained how after he sat next to and talked with Mrs. Jones who is “very fair and to many people looks to be White. It is evident the driver seemed to resent my talking to her and told me to move to the rear” because “he didn’t ask the lady to move.”55

Robinson admitted to using profanity but not to the excess and extent the Whites eager to frame him had portrayed. Robinson made it clear that “I Don’t Mind Trouble but I do believe in Fair Play and Justice. I feel I’m being taken in this case and I will tell people about it unless the trial is fair.”56 Robinson concluded the letter by inquiring whether he should seek media attention on the case or if doing so would be ill-advised.

Gibson responded that his office could take no action on Robinson’s behalf prior to the trial.57 Perhaps unbeknownst to Robinson, however, Gibson did pass Robinson’s letter on with Gibson’s own handwritten annotation on the first page that read: “This man is the well-known athlete. He will write you. Follow the case carefully.” Developments leading up to and through trial in Robinson’s case would be closely watched by the military’s higher ups in Washington, D.C.

Some of Robinson’s fellow Black servicemen wrote letters to the Black press alerting them of Robinson’s impending court martial trial.58 In response, the Black newspapers wrote about it, as well as numerous other mistreatments of Black servicemen, to provoke serious discussions around whether Blacks should risk their lives to fight for freedoms abroad when racism and unfairness flourished at home in the U.S.59

Understandably concerned he would not be afforded solid defense counsel or a fair trial, Robinson also began taking steps to address the former. After his arrest, Robinson sent a letter to the NAACP in New York seeking legal representation.60 Unfortunately for Robinson, the NAACP did not reply until the day after Robinson’s court martial trial ended.61 Despite the hopelessness of the situation, Robinson was not without hope.

A deeply religious man, Robinson relied heavily on his faith in God and rested in knowing that, though Robinson was not perfect and made mistakes, God still loved him and would come through for him.62

Unbeknownst to Robinson, as inside and outside pressures mounted over his fast-approaching trial, key personnel in Camp Hood’s Inspector General’s Office (“IG Office”) — the military organizational authority in charge of investigating whether or not court-martial charges should be filed and prosecuted — began expressing grave concern over proceeding with the court martial trial as originally planned.

One such IG Office personnel, Camp Hood’s Colonel Kimball sought assistance and direction from higher level command at XXIII Corps. In a transcription of a July 17, 1944, phone call between Colonel Kimball and XXIII Corps’ Chief of Staff Colonel Buie, Kimball explained that Robinson’s was “a very serious case, and it is full of dynamite.”63

And as such, the cased needed “very delicate handling” “by someone off the post” since “[t]his bus situation here is not at all good, and I am afraid that any officer in charge of troops at this post might be prejudiced.”64 In response to Kimball’s plea, Colonel Buie explained that though he “would like to send an inspector right away, … none was [currently] available.”65 Desperate for any outside help Buie could lend to this serious situation, even if only temporary, Kimball asked Buie if, alternatively, he could send an inspector down to Camp Hood in about a week which would give Kimball’s inspectors time to conduct the preliminary investigation and have it ready for Buie’s inspector when they arrived. Buie agreed to send an inspector, assured Kimball that his office “want[ed] to stay right with you on” this case, and repeatedly asked Kimball to “in the meantime, be sure to keep us informed” of any changes in the case and “to call at any time.”

Kimball’s concerns and further investigations undoubtedly led to the reduced charges that would eventually be put forth against Robinson at trial.

Robinson’s defense team eventually would consist of three attorneys. Initially, two attorneys were appointed as Robinson’s defense counsel: Lieutenant William A. Cline, a native Texan from the small town of Wharton, and an assistant defense counsel, First Lieutenant Joseph C. Hutcheson of the 635th Field Artillery Battalion.66 Although some incorrectly credited Cline with Robinson’s defense, Robinson himself noted the exact opposite in his autobiography, I Never Had It Made.

Robinson clarified that his first lawyer, Cline, was a southerner who pleaded prejudice.67 Indeed, prior to trial, Lieutenant Cline candidly told Robinson that he did not feel comfortable defending a Black in such a case.68 Additionally, Cline’s title business background meant he did not engage in much adversarial litigation matters and, therefore, had a little courtroom experience. Wisely then, Robinson sought to add his own counsel. Thus, the third attorney, First Lieutenant Robert H. Johnson of the 679th Tank Destroyer Battalion, was added after Robinson stated he wanted Johnson to serve in his defense as his individual counsel.

The Court Martial Trial of 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson

Depending on the historical document viewed, at 1:45 p.m. on either Aug. 2 or 3, 1944, the court martial trial of The United States v. 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson, 0-10315861, Calvary, Company C, 758th Tank Battalion began.69

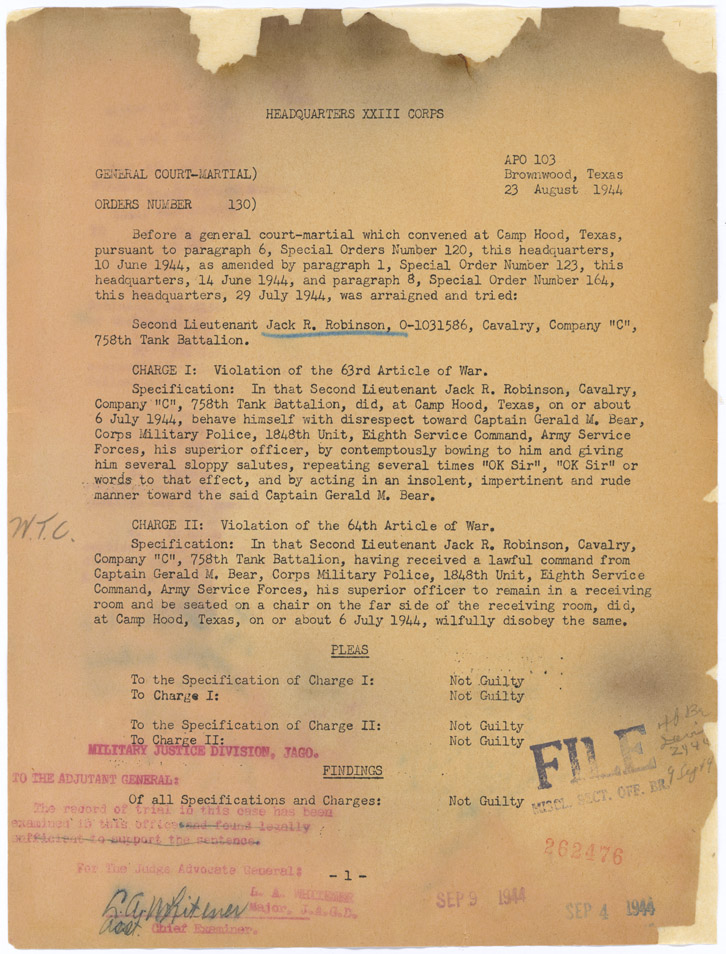

Robinson faced two charges. The first violation of Article of War No. 63 accused him of behaving with disrespect toward Captain Gerald M. Bear, CMP, his superior officer by allegedly acting insolent or in a rude manner towards the captain, sloppily bowing and saluting Bear and repeating the words “OK, sir.” The second charge was a violation of Article of War No. 64 for the alleged willful disobedience of a lawful command of Bear for Robinson to remain in the receiving room and be seated on the chair on the far side of the receiver room.

The three other charges that were more closely tied to the bus events had been prepared against Robinson but were abandoned prior to trial. The first accused Robinson of disrespect towards the officer of the day, Captain Wiggington, because Robinson allegedly told the Captain that if “any private, or you, or any general, calls me a nigger and I’ll break them in two. I don’t know the definition of that word,” and by speaking to Wiggington in an insolent, impertinent, and rude manner.

The other two charges involved the two civilians. One charge accused Robinson of abusive and vulgar language towards the civilian bus driver in the presence of ladies, and the third charge accused Robinson of allegedly telling civilian passenger Mrs. Poitevint you better quit fucking with me. The prosecution’s strategic decision to abandoned the two civilian charges complicated Robinson’s defense. Robinson’s defense counsel would have to figure out a strategy that could minimize the potential negative impact to Robinson’s overall defense brought on by the fact that now his lawyers would no longer be able to connect what happened on the bus with what subsequently occurred at the MP station.

Robinson’s defense team decided it best not to dwell on Bear’s racism. Racism was too subjective and, though they would address it where needed, given the prevailing tone of the day among White southerners, focusing solely on racism could backfire. Instead, defense would strategically focus on the objective facts and chain of events to highlight any missteps in Bear’s execution of his authority.

Their goal was to lay the groundwork and drive home the theme that Robinson had in fact not been insubordinate to Captain Bear as charged.70 Upon a closer look, the defense argued, rather than insubordination, the facts would reveal the confusion and misunderstanding that resulted from Bear’s unclear orders and mismanagement of the situation.71

Unfortunately, the trial record is unclear which of Robinson’s three attorneys questioned who or the role each played in his courtroom defense during the trial.72 Robinson recalled the great job the young Michigan defense attorney did and how he, not Cline, “had a way of rephrasing the same question in so many clever ways that anyone who was lying would have a hard time not betraying himself.”73 Ultimately, skillful questioning of Bear and the other prosecution witnesses by the defense brought out inconsistencies about how Bear had handled Robinson that night and especially about what Bear ordered Robinson to do. The defense’s cross-examination of Bear sought to exploit the likelihood that Bear had not given Robinson specific instructions about where to wait.

To this same end, during the cross-examination defense counsel drew out how Bear had declined to answer when Robinson repeatedly sought clarification by asking if he was under arrest and juxtaposed that with Bear’s decision to send Robinson back to the hospital under guard in a MP vehicle. Testimony exposed how Bear and others had probably become incensed and enraged when Robinson insisted on correcting Bear’s civilian stenographer’s seemingly deliberate mis-transcription of his statement.74 Indeed, Cline testified that for Bear, it seemed to have developed into a kind of personal matter. With the exception of a general consensus that Bear had ordered Robinson to be “at ease,” witness accounts differed on what Bear ordered Robinson to do when leaving the MP Guard Room.75

Almost all of the Whites involved were genuinely baffled that Robinson disliked being badly treated. Only one White witness, Mrs. Rubie Johnson, gave an account of events on the bus that were almost exactly as Robinson had relayed them. Mrs. Johnson testified about the exchange between Robinson and the driver but reported no obscenity spoken by Robinson to anyone, including her friend Mrs. Poitevint.

Finally, Robinson’s turn to take the stand to testify in his own defense arrived.76

Robinson’s faith enabled him to remain composed under fire. Robinson admitted that he had used obscene language only once after being provoked, but not towards Mrs. Poitevint.77 He denied having behaved or mocked contemptuously against his superior officers, or any officer. Robinson testified that he did object to being called a nigger by the private, or anybody else and admitted that he told the captain that “if you call me a nigger, I might have to say the same thing to you. I do not consider myself a nigger at all. I am a Negro, but not a nigger.”

Robinson explained, in response to the question do you know what a nigger is, that the dictionary’s definition says the word pertains to the Negro but it is also a machine used in a sawmill for pushing logs into the saws. However, as a youth, his grandmother, who had been a slave, had given him a good definition. She said the word pertained to no one in particular but meant a low uncouth person.78 Since Robinson did not consider himself to be low or uncouth, he testified, he was not a nigger.

The defense also called several character witnesses from the 761st Tank Battalion on Robinson‘s behalf including Captain James R. Lawson and Second Lieutenant Harold Kingsley and Colonel Paul Bates himself.79 Bates was so eager to support Robinson, and more than once, when the prosecution tried to reign him in, Bates testified about how he held Robinson in high regard; that his general reputation and ability as a soldier were both excellent; that Colonel Bate’s had tried to have Robinson assigned, rather than merely attached, to the battalion because of his excellent work; and that he would be satisfied to go into combat with Robinson.80

The defense concluded for the panel that Robinson had violated no articles of war as charged.81 Rather, the charges before the court were the result of a few individuals exacting their racial bigotry on what they considered an “uppity” Negro who had the audacity to try to exercise rights that belong to him as an American and as a soldier.82

The Verdict

The trial lasted over four hours. In a remarkable turn of events, Robinson secured the minimum of four “NG” (i.e., Not Guilty) votes, secret and written, that were needed to acquit him. He was found not guilty on all specifications, and on all charges, and was later exonerated for the charges. In the end, the trouble Robinson experienced gave way to the justice he had prayed so earnestly for.

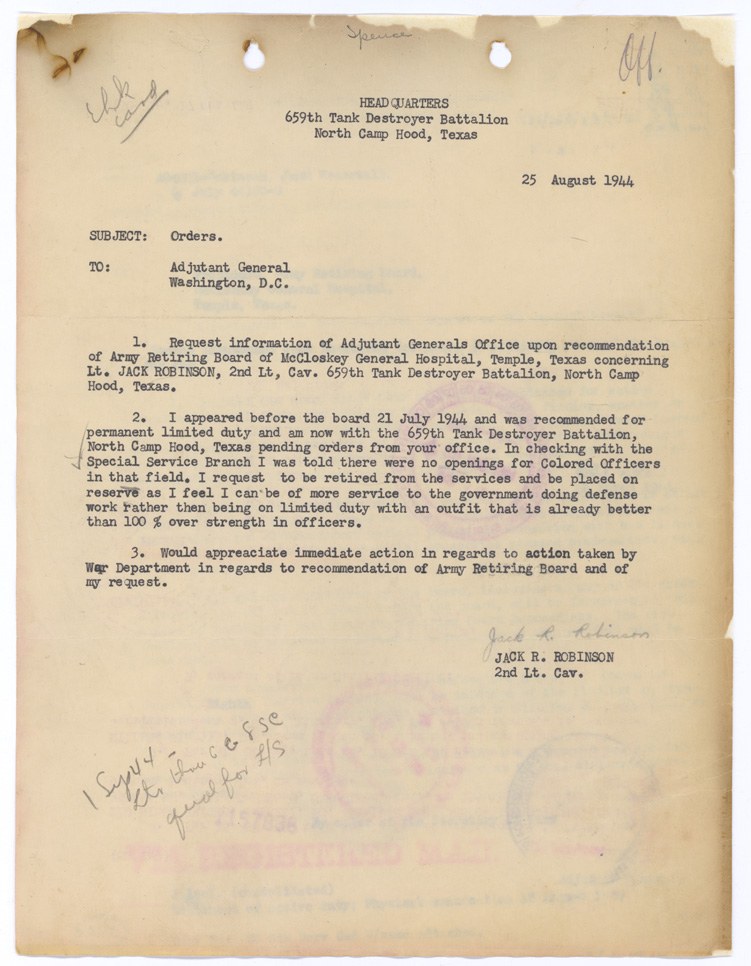

Acquitted, Robinson returned to the 758th Battalion at north Camp Hood. On Aug. 24 of that same month, Robinson was formally reattached to the 761st Tank Battalion.

However, by the time of his reattachment, the battalion had already left Camp Hood.83 Rather than seek to rejoin them and serve overseas, Robinson began taking steps to request to retire and leave the army with an honorable discharge.84 This decision was almost certainly reached after Robinson grappled with the harsh reality of what he had just endured at the collusion of so many.

The obvious question was whether it wise for Robinson to risk his life in an army that had allowed the racism of some to misuse the system, attempt to pervert justice, and unfairly subject him to an unwarranted court martial trial reserved for the most heinous of military crimes. Meanwhile, by Nov. 7, 1944, the 761st Tank Battalion, led by Colonel Bates with thirty Black officers and five White officers, went into action, fighting for 183 consecutive days and helping to liberate the Buchenwald concentration camp.85 Back in the U.S., Robinson’s retirement efforts eventually paid off because, by Nov. 28, 1944, he was “honorably relieved from active duty” in the army “by reason of physical disqualification.”86

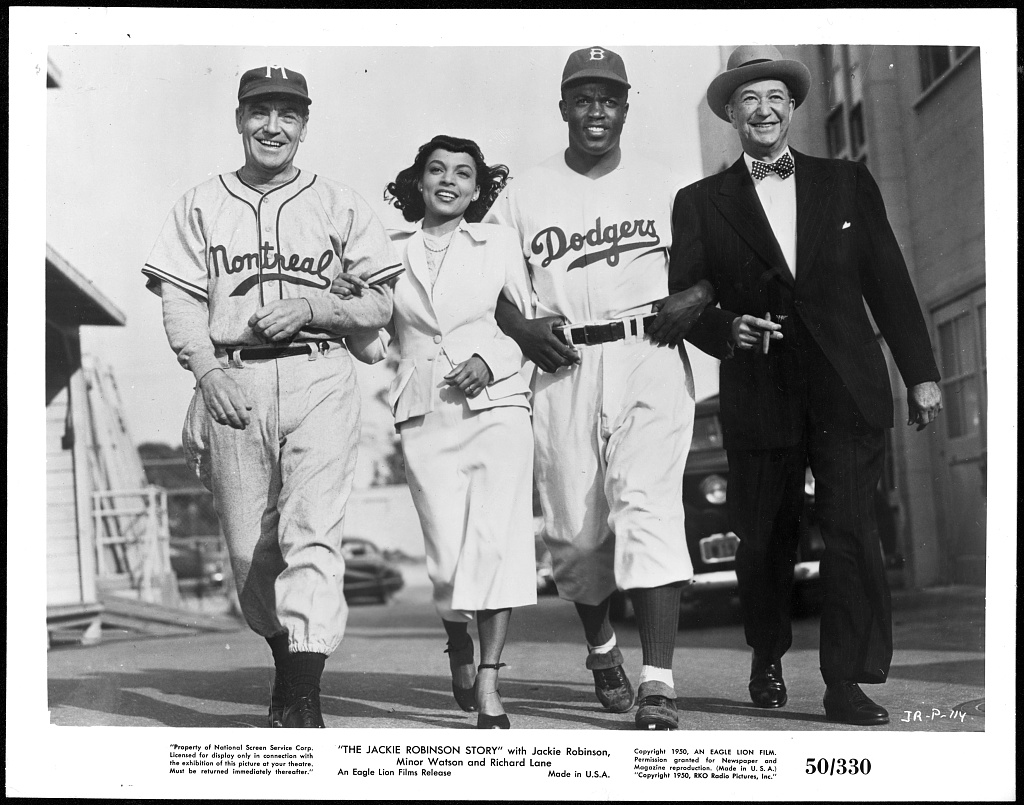

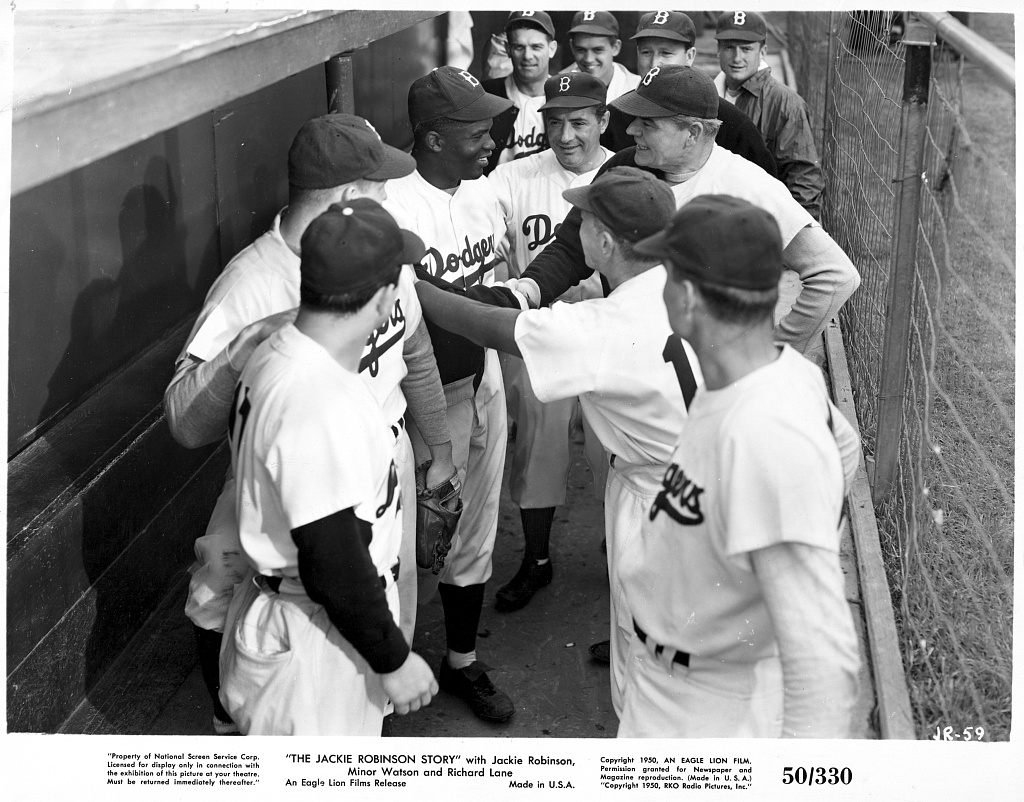

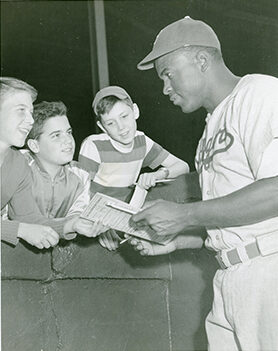

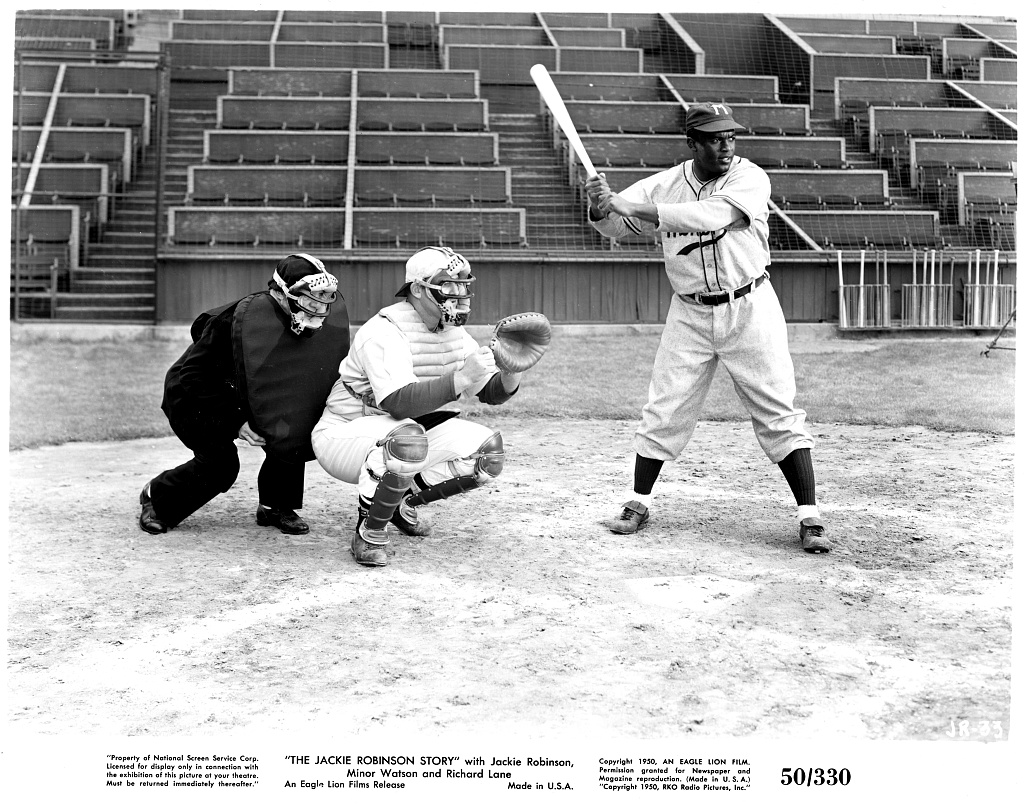

Less than three years later, in April 1947, Robinson would, while donning Dodgers’ blue and the number 42, embark upon his biggest integration test to date: debut in MLB as its first Black professional player.

Alia Adkins-Derrick is the Managing Partner and a Certified Mediator at Adkins Lawyers, PLLC, a premier boutique law firm in Dallas and Houston, Texas. Known for her fierce written and oral advocacy, she helps clients protect their interests and their bottom lines by providing the smart legal defense, solutions, and representation clients need to tackle a myriad of complex employment, business, contract, personal injury, and civil litigation issues. As a mediator, she focuses on putting control back into the hands of the parties by identifying workable solutions to help parties reach settlement. Ms. Adkins-Derrick has also served as an Adjunct Law School Professor dedicated to helping the next generation of lawyers hone their advocacy skills.

Author’s Note: Special thanks to Robert J. Adkins for his diligence in locating digital copies of the original military personnel, medical, and court martial trial documents of 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson.

- Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson, age 25, wrote this in his letter to Truman K. Gibson ahead of being made to appear in Fort Hood, Texas before the military’s highest level trial court reserved for trying service members for the most serious of crimes. See Letter from Jack R. Robinson to Truman K. Gibson (July 16, 1944). ↩︎

- In May 2023, Fort Hood Texas was renamed to Fort Cavazos in honor Texas born General Richard Cavazos, who was the first Latino four-star general and first Latino brigadier general in the U.S. Army. ↩︎

- Vice President Harry S. Truman was sworn in as president of the United States on April 12, 1945, after President Franklin D. Roosevelt died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 75 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. at 84. ↩︎

- Id. at 84-85 ↩︎

- Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 12 (1995); Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 85-87 (1997). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 87 (1997). ↩︎

- See John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 2. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 13 (1995) ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 91 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. at 92-93. ↩︎

- See Special “Extract” Orders No. 300, Dec. 9, 1943 (releasing Robinson from Fort Riley, Kansas and reassigning him to Fort Clark, Texas). ↩︎

- WIKIPEDIA – Cavalry training at Fort Clark ceased in January 1944. That year, the U.S. Army deactivated the cavalry branch and merged it with the armor branch. Finally, in June 1944, after full mechanization of the cavalry, the government ordered the closure of Fort Clark, one of the last horse-cavalry posts in the country. (last visited Aug. 30, 2023). ↩︎

- Special “Extract” Orders No. 2, Jan. 4, 1944 (assigning Robinson to Brooke General Hosp. at Fort Same Houston, Texas). ↩︎

- Id.; Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 98 (1997). ↩︎

- See Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 99 (1997). ↩︎

- See Special Orders No. 47, Apr. 20, 1944 (Assigning Robinson to Company B of the 761st Tank Battalion); Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 99 (1997). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 99 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 4,; Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 99 (1997). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 100 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- See John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 4. ↩︎

- See John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 4. ↩︎

- Request of Assist. Hosp. Registrar Robert Gilmore for issuance of special order confirming “Government motor transportation utilized” to “Transfer of Officer” 2d Lieutenant Robinson to McCloskey Hospital “for further observation, treatment and recommendation.” ↩︎

- Proceedings of Disposition Board, June 26, 1944 (convening at McCloskey Hospital and issuing fitness for duty medical opinions and recommendations). ↩︎

- Proceedings of Disposition Board, June 26, 1944. ↩︎

- See John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 10; Sworn Statement of Milton Renegar ¶2, July 8, 1944. ↩︎

- Sworn Statement of Milton Renegar ¶2, July 8, 1944 (Renegar claimed that he acknowledged Robinson’s officer rank and politely asked Robinson: “Lieutenant, if you don’t mind I … would like for you to move back to the rear of the bus if you don’t mind” because he knew he’d soon reach the bus stop where quite a few White ladies who ride his bus around this time each night would board and knew they’d not want to ride all “mixed up with them [Coloreds].”). ↩︎

- Compare Letter from Jack R. Robinson to Truman K. Gibson (July 16, 1944) with Sworn Statement of Milton Renegar ¶2, July 8, 1944. ↩︎

- Disputed Sworn Statement of Jack R. Robinson ¶3, July 7, 1944. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Sworn Statement of Ruby Johnson ¶2, July 8, 1944. ↩︎

- Sworn Statement of Milton Renegar ¶2, July 8, 1944 ↩︎

- Disputed Sworn Statement of Jack R. Robinson ¶3, July 7, 1944. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Sworn Statement of Bevlie B. Younger ¶2, July 7, 1944. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 20 (1995). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 20 (1995); Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 104 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 104 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Special “Extract” Orders #159, July 6, 1944 (releasing Robinson from the 761st Tank Battalion and assigning him to the 758th Light Tank Battalion. ↩︎

- See Letter from Jack R. Robinson to Truman K. Gibson (July 16, 1944). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 7. ↩︎

- Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 22 (1995). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 104-105 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 105 (1997). ↩︎

- See Military Transcript of Phone Conversation between Colonel Kimball & Colonel Buie (July 17, 1944, 9:30 a.m.); and John Vernon, Jim Crow: Meet Lieutenant Robinson, PROLOGUE MAGAZINE OF U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVE & RECORDS ADMINISTRATION, Spring 2008, Vol. 40, No. 1, at 12-13. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- See Military Transcript of Phone Conversation between Colonel Kimball & Colonel Buie (July 17, 1944, 9:30 a.m.). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 105-106 (1997). ↩︎

- See Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 22 (1995) ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 105-106 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. at 105; War Department Summary Sheet (attaching letter for signature of the Secretary of War to inform Senator Downey of outcome of Robinson’s court martial trial and acquittal on all charges.)(Aug. 17, 1944). ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 107 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at 106. ↩︎

- See Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made: An Autobiography, 22 (1995) ↩︎

- Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography, 107 (1997). ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at 108. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at 108-109. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at 109. ↩︎

- Id. at 109. ↩︎

- Id. at 109-110. ↩︎

- Id. ↩︎

- Id. at 110. ↩︎

- Id. at 111. ↩︎