© 2014 The Texas Lawbook.

By Sol Villasana

Contributing Writer to The Texas Lawbook

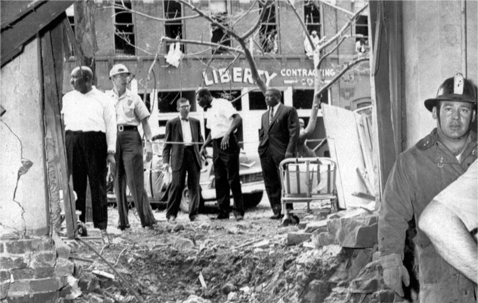

(May 24) – The bomb blast blew out a wall of the church. Blood and shattered stained glass covered splintered furniture and scorched Bibles. The smell of dynamite still hung in the air.

Rainwater from the night before had pooled in the roadway and broken sidewalks. Newly-minted Harvard lawyer John Andrew Martin had driven down Sixteenth Street many times before to his office with the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department at the federal courthouse in his hometown of Birmingham. He’d seen the consequences of the other bombings.

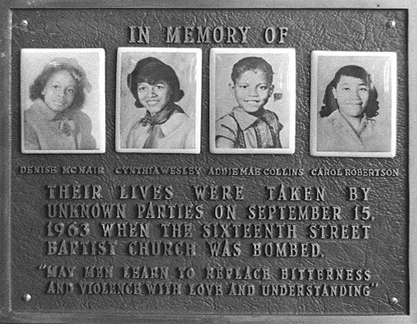

But September 15, 1963, the twenty-first bombing, was different. Four African American children – Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley—were killed in that church.

Martin pulled his Pontiac over near the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, found a phone and called his boss. He asked for instructions and was told to stay put. Others from the Civil Rights Division were on their way. He waited as people around him cried in anguish.

The carnage, Martin would recall years later, “was sickening.” It was the beginning of another bad week in what Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Harrison E. Salisbury of the New York Times called the “fear and hatred” of the Old South.

What had been the Southern system of legal racial segregation in every facet of life had, at least since the 1954 Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education that upended state imposed separate unequal educational systems, become increasingly defended by Southerners through violence.

Blacks and anyone attempting to impose the new federal civil rights law in the South were more and more targets of horrific, violent attacks.

Now, Mr. Martin’s son had come back to Alabama from Harvard to help enforce those laws.

No one, especially Southerners, thought that would be easy. In the wake of the latest bombing, rioting had begun, two black youths were shot by police, and 500 National Guardsmen were being sent to Birmingham.

The day after the bombing, President John Kennedy stated “if these cruel and tragic events can only awaken that city and state—if they can only awaken this nation to a realization of the folly of racial injustice and hatred and violence, then it is not too late for all concerned to unite in steps toward peaceful progress before more lives are lost.”

Fearing that more lives would be lost, Martin’s father slowly pulled the car to a stop at the courthouse. Putting the car into park he worriedly looked at his son and quietly said, “I wish I’d never sent you to Harvard.”

This year, we commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Next year marks fifty years since President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

It has been sixty years since the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown. At the distance of fifty or sixty years, many lawyers today might be excused for thinking of these laws as ancient history.

They would be wrong.

Talking today with Martin (he’s now 76) in his downtown Dallas office, these events are not obscure historical events. They are personal landmarks. They are part of his personal journey toward justice.

Nothing in Martin’s background marked him for a role in the civil rights movement. While public service was always close to home (his father was elected superintendent of Clay County, Alabama schools, his mother was a social worker, and a cousin, Hugo Black, was a U.S. Senator and a Justice on the nation’s Supreme Court),

Martin was a somewhat typical white Southerner. He would remember never having heard the word “ghetto” in his home. The family had a black maid, Cora Lee.

“Blacks didn’t have last names [in the South] in those days” Martin recalls.

If anything, Martin was, like many Southerners, annoyed and offended by Northeasterners’ attacks on Dixie. One of Martin’s roommates at Harvard was Ernest E. Smith, now a law professor at the University of Texas.

A Texan, Smith recalls how folks at Harvard assumed Southerners were rubes and bigots.

When Salisbury came to Birmingham in 1960 for the New York Times, he wrote a scathing series on Southern bigotry and intolerance. Salisbury’s “fear and hatred” stories were universally condemned by Southern leaders.

At Harvard at the time, a young Martin, also feeling that Alabama was being unjustly characterized by Salisbury’s writings, even wrote to the Times editor to criticize its reporting.

Martin remembers, “I wanted to fit in.”

When Martin looked to Alabama’s brightest minds and leaders to debunk Salisbury’s accusations, he was painfully disappointed. While protestations and consternations toward Salisbury were great, no one down South could challenge the facts behind his reports.

With a certain scorn in his tone, Martin recalls, “they couldn’t rebut one fact.”

Back at Harvard, Smith also used religion to challenge Martin and others about Southerners’ unsavory views on race relations. How could anyone call himself or herself a Christian and not recognize racism’s inconsistency with Christian teachings?

All these lessons were the beginning of Martin’s journey out of the darkness that had enveloped the South for generations and toward a quest for justice for all individuals under law.

“What am I living in?” Martin finally asked himself.

He determined that the South’s resistance to civil rights legislation “was not right in our democracy.”

By the time Martin graduated from Harvard in 1962, he realized that the South needed to change. Remembering the South’s situation years later, Martin would say “it was a way of life” and nothing could change it but “force.”

While he could have gone directly into any big law firm, he decided he had to do something greater and more challenging with his law degree. He joined the Civil Rights Division.

At the time, Southern Jim Crow laws were preventing African Americans from voting. Even registering to vote was dangerous. The Civil Rights Act of 1957 made it unlawful to interfere with the right to vote in federal elections.

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 required, among other things, that all records and papers relating to prerequisites to voting, such as payments of poll taxes and literacy tests, be preserved. Such record keeping would prove to be important because, if a court found a “pattern or practice” of discrimination in the state’s voting qualifications, it could order a remedy.

Not surprisingly, Martin’s supervisors wanted him in the Deep South.

“It was important to have boots on the ground,” Martin remembers.

As a Southerner, he wouldn’t stand out. He could come and go, with some ease, among those intent on opposing voting rights for African Americans. And importantly, he could gather information to help the Justice Department plan for and respond to Southerners’ resistance to the new laws, especially if the resistance involved violence.

These were definitely not your typical tasks for a young lawyer. Aside from the novelty of Martin’s new assignment, the job was also dangerous.

One of Martin’s first forays into his new job was in the summer of 1962 at Oxford, Mississippi, the home of the University of Mississippi, Ole Miss.

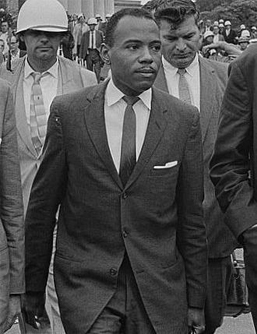

James Meredith, a young African American, applied to Ole Miss. While other blacks had applied before only to be rejected and dissuaded, Meredith made it clear (he had the solid backing of NAACP lawyers) he was intent on going despite the massive obstacles the university and the state would place in his way.

Martin, posing as an Ole Miss student, was to go undercover and gather information to help answer to those questions.

Martin’s undercover work at Ole Miss didn’t start out auspiciously. He was soon recognized by students who knew him from Birmingham. Nevertheless, by circulating as a student in the dorms and fraternity houses, he was able to get a good picture of what the Justice Department might expect once Meredith arrived on campus.

Clearly, the administration and state government would not help Meredith to register at the university. Further, and more ominously, state authorities would not promise to protect him from violence.

While Mississippi highway patrol troopers were to be present in large numbers at Oxford, federal authorities could not count on their assistance in integrating schools. Actually protecting Meredith would fall to the U.S. Marshals, federal troops, and a handful of Justice Department lawyers, including Martin.

After gauging the students’ attitudes on campus and feelings of the townspeople, Martin didn’t sense there would be violence once Meredith enrolled. Martin had seen and heard language and taunts laced with racial hate, had seen the bitterness from students and townspeople directed not only at blacks, but also to those whites who were sympathetic to Meredith’s cause.

But for Martin, violence didn’t seem in the cards. It would be ugly, yes, but Southerners wouldn’t resort to violence against federal court orders, against the basic rule of law. He’d recall “there was nothing I could pick-up on” in his undercover work at Ole Miss that suggested violence. Martin would be terribly wrong.

Federal authorities helicoptered Meredith onto campus on Sunday, September 30, 1962.

The plan was that on the next morning, accompanied by U.S. Marshals and Justice Department officials, most prominently, the Civil Rights Division’s John Doar (Martin’s boss and mentor), Meredith would register and attend classes as Ole Miss’ first black student.

By about 4 p.m., the marshals began to surround the campus building where Meredith would register the next day. By late afternoon, more than a 1000 students had gathered around the marshals. The crowd began to jeer and curse at the marshals. State Highway patrolmen watched and did nothing.

By late Sunday afternoon, reports were coming in that cars and trucks carrying numerous men were on the roads heading toward Oxford and the university. Noticeably, the crowd confronting the marshals grew larger, at least 2000, and more aggressive.

At about 7 p.m., the mob began to throw rocks, bricks and pipes at the marshals. There was gunfire.

Then the crowd surged toward the marshals’ line. Protecting themselves, they responded with tear gas.

The rioting had begun.

It would go on all night and into the early morning, spreading into the town of Oxford. It would not be until 6:15 a.m. that authorities declared the area secure.

At 8 a.m. the next morning, James Meredith, surrounded by a phalanx of federal officials, registered for classes.

Two people had been killed and many injured in the rioting. At least 160 persons had been arrested.

Back home in Washington, D.C., where he’d gone just a few days before to be with his wife who was ill, Martin pick up the newspaper from his lawn and saw the terrible headlines from Ole Miss. Shocked, he stood there in his front yard and read of the riot.

He had been wrong.

Southerners would violently defy the law. He now knew that his work for the Justice Department would take him to what he’d call “enemy territory,” and that the journey toward justice in the South would be lined with what President Kennedy had hoped to avoid: “more lives…lost.”

Martin went back to Oxford and, along with U.S. Marshals and other Justice Department lawyers, continued to protect Meredith for several more months.

A 1963 photograph from the Memphis Press-Scimitar shows Martin at Ole Miss. He is tall and, even then, has thinning hair. While Martin now characterizes his work as “babysitting” Meredith, after prodding, he admits to ugly and potentially dangerous confrontations.

One day, walking with Meredith along a campus road, a car slowly came up alongside them. Its occupants called out in a friendly tone causing Meredith and Martin to turn toward the car. Then, cursing racial epithets, they speed off.

Meredith was ostracized, constantly harassed, and isolated at Ole Miss. Sitting in the school’s cafeteria with Meredith, Martin would remember that “you could cut the hate in the room with a knife.” Meredith would go on to eventually graduate from the university in 1963.

Martin’s work in “enemy territory” was far from over. By mid-1963, Martin was on a plane to Americus, Georgia. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) workers had been making gains in Americus registering African Americans to vote. Their success did not go unnoticed.

Three SNCC and one Congress of Racial Equality volunteers were arrested and charged under Georgia’s 1871 Anti-Treason Act with insurrection. which carried the death penalty. The Justice Department was intent on getting the charges dismissed, but it would be a hard legal fight. Martin was to cover the legal proceedings that went on for months. Eventually, a federal district court dismissed the charges.

In the summer of 1964, Martin found himself handling calls to the Civil Rights Division in Washington. His boss was in Mississippi. Three civil rights workers, Mickey Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney were missing in Neshoba County, Mississippi.

Fielding countless calls about updates on the search, Martin took three calls on one day that were the most painful of his life: Goodman’s mother was asking about the fate of her son.

By now, Martin had experienced enough of Mississippi to fear the worst. “It was hard to talk to her,” he says. On August 4, 1964, forty-four days into the search, the bodies of the missing men were found buried in an earthen dam southwest of Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Martin’s tenure at the Civil Rights Division was not all headlines and dealing with the Old South’s most horrific cases. Much of the Division’s time was spent trying to gather evidence of discrimination in voting for litigation.

“We’d live in a rented car for two or three weeks,” making contacts with the black communities and trying to locate and interview African Americans that had been denied the vote, he said. Preparing cases for trial could be tedious, frustrating and time consuming.

The U.S. Supreme Court would note in the 1966 case of South Carolina v. Katzenbach: “Voting suits are unusually onerous to prepare, sometimes requiring as many as 6,000 man-hours spent combing through registration records in preparation for trial.”

Despite these problems, the Civil Rights Division lawyers won cases. Martin would be involved in one of the Division’s first successes in enjoining state officials from intimidating blacks for the purposes of interfering with their right to vote.

The success came in Terrell County, Georgia. In late July 1962, an SNCC field representative urged the congregation during prayer meeting at the Mt. Olive Baptist Church in Sasser to register to vote.

After church, when the church-goers attempted to leave the parking lot, their way was blocked by cars and trucks filled with angry whites. Several cars were owned by local law enforcement officials. No one was hurt, but a few days later, the church was burned to the ground. Martin was again on a plane to Georgia.

Martin and another Division lawyers spent the next several days meeting with black leaders in the area, interviewing witnesses, and preparing affidavits. They then filed a petition naming the sheriffs of Terrell and Sumter Counties, and others, as defendants.

Doubting any arson, a judge denied the request for temporary relief. As if the judge’s decision gave comfort to the arsonists, another black church was burned. Finally, before another judge, the Civil Rights Division prevailed and enjoined the officials from further interference in the voting rights of blacks in Terrell County.

Today, Martin has the note written to him by Attorney General Robert Kennedy thanking John for his “fine work” in Terrell County proudly hanging on his office wall.

Thinking back on his time in Mississippi, Martin admits the state was “pretty scary.” He remembers being pushed once at a march in Greenwood, but he only recalls one time where he felt personally uncomfortable. It was his last night in Mississippi. He was to go home the next day. Driving down yet another dark, rural road he couldn’t get over the feeling that, at the next curve, there would be the KKK, blocking his way.

Martin left the Justice Department in 1964, but the battle for justice continued in Southern streets and courtrooms.

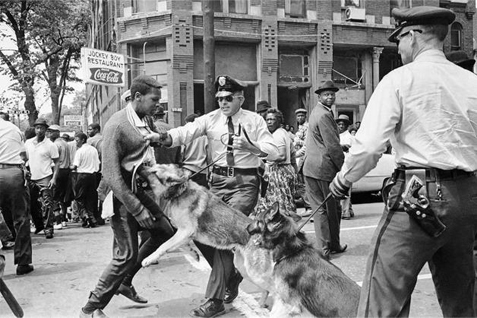

In March 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a large march for black voting rights from Selma to Montgomery. The marchers were attacked by police and state authorities upon crossing a bridge in Selma. Officials used Billy clubs, tear gas and police dogs against the marchers in one of the bloodiest police riots in history.

In Washington, President Johnson decided the time was right to push for new, stronger voting rights legislation. Thanks to the years of work of lawyers like Martin in the Civil Rights Division, documentation existed to reinforce the necessity of the proposed bill.

By the summer, President Johnson had signed into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Martin, reflecting back, asserts that the Act “could not have been passed in such detail, manner and speed without the Civil Rights Division’s work on voting rights cases in the South.”

Acknowledging the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was “absolutely revolutionary,” Martin feels it was the 1965 Voting Rights Act that “really changed society in the South more than anything else….”

Martin, his wife, Anne and son Charlie, came to Dallas in 1964 to join the law firm of Carrington Coleman as a business litigator. As Senior Counsel, he’s still with the firm, coming to work every day.

He immediately became involved in civic affairs and volunteered countless hours to pro bono activities including work with legal aid groups. By 2003, his community work was so well known that he received the Dallas Bar Association’s prestigious Justinian Award for his long record of volunteerism.

Even today, Martin serves on the executive committee of the board of directors of the YMCA of Metropolitan Dallas and is a trustee of LaunchAbility. But it was Martin’s years (1981-1986) as a member of the board of trustees of the Dallas Independent School District (DISD) that, it could be argued, proved to be his biggest challenge.

Desegregating Dallas public schools was difficult and painfully slow. Despite Brown, by 1961, Dallas had the largest segregated school system in the South. Several cases had been brought against the DISD to desegregate its schools. The late Dallas judge L.A. Bedford, Jr. worked on one of the first cases, alongside future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Yet, delaying desegregation through the courts seemed the only way the DISD and the Dallas business community would respond to Brown.

Edward “Ed” Cloutman III recalls he “was a green lawyer” when Mr. Sam Tasby walked into office at Dallas Legal Services in 1970. He wanted Cloutman to file a federal lawsuit charging the DISD with maintaining a dual school system. That fall, Cloutman did, and what would be called the Tasby litigation began.

The case would go on for the next 33 years until Judge Barefoot Sanders finally decided that “the segregation prohibited by the United States Constitution…no longer exists in the DISD.”

After the first trial in Tasby in 1971, the judge found that “a dual system still existed” in the DISD. One of the most contentious issues and ordered remedy was the busing of children.

By the time Martin was elected to the DISD board in 1981, Tasby had bounced back and forth several times between the district court and the Court of Appeals in New Orleans. It was also the year that Sanders issued his opinion in Tasby “that vestiges of state-imposed racial segregation remain in the [DISD].” What would the DISD board do with Sanders’ new order?

For Martin, newly elected DISD board president (his fellow board member, Richard Curry, remembers him as “the darling of the business community”), the answer was simple: appeal.

Sanders’ order was “awful,” says Martin. His encounters with federal judges in his early days in the South had seriously tempered his attitude toward the federal judiciary. Reflecting on his disagreement with Sanders, Martin says he “didn’t think one man [Sanders] was smarter than the community.”

Cloutman recalls that part of Martin’s difficulty in dealing with Sanders may have come from trying to “wear two hats; as [DISD] board president and as a lawyer.” Whatever the reason, Martin and Sanders’ relationship became, according to Cloutman, personal.” Raised voices between the two were not uncommon.

When asked to jibe Martin’s civil rights work in the 1960s with his difficulty with Judge Sanders’ desegregation order, Cloutman explains that, by then, Martin represented “the old way [of] knocking down [racial] barriers.”

Others might argue that Martin was actually prescient about the busing issue, and properly advocated the central principal of local control of educational resources.

Today, few believe busing worked, aside from forcing school districts to canal more resources to minority students. Sixty years after Brown, the DISD, like most public school systems, is as segregated as ever.

Sadly, today minority public school children are as isolated from white children as Meredith was at Ole Miss in 1962.

One thing was clear: Martin’s work on the DISD board was taking a toll on him. Fellow DISD trustee Roberto Medrano says Martin “polarized the board.”

Martin, says, Curry, while “a smart guy” made “no attempts to compromise.”

When the time came for the board to elect a new president, Martin lost. While he continued to serve on the board until 1986, Martin says he realized “I couldn’t do anything to stop the federal onslaught. I had enough of it.”

Today, reflecting on his long, illustrious career in both private and public service, Martin admits race relations are still “not perfect.”

“Everyone talks about how bad things are today, but they just don’t know,” he says. “You can’t compare today with the way the Old South was run.”

Yet, shockingly, we are still reminded of those old days. Earlier this year, three Ole Miss students were charged with placing a noose around the neck of the statute of James Meredith, which stands on the university’s campus. Our differences still conjure up “fear and hatred.”

The Rev. Dr. Zan Holmes, who co-chaired the Tri-Ethnic Committee appointed in the 1970s by the judge to help DISD’s Tasby desegregation plan, finds that we still fail to embrace, fail “to celebrate diversity,” even though our nation is more diverse than ever before. And it is becoming more diverse.

By 2043, the U.S. Census Bureau predicts the U.S. will be a majority-minority country. Reflecting that irreversible trend toward diversity, almost 70 languages are spoken by students in the DISD today.

Today, our journey toward justice can be liked to those early marches through the Old South. It would be wrong to think that journey is over. Justice is still too elusive in our legal system, especially for the poor, for immigrants, for the dispossessed.

Early Dallas civil rights lawyers like Martin, Cloutman, Frank Hernandez, Adelfa and Bill Callejo, Bedford, W.J. Durham, C.B. Bunkley, Mike Daniel, and Betsy Julian joined that march a long time ago. Their courage changed our world.

It will continue to be a long, legal journey, fraught with obstacles and setbacks, such as last year’s Supreme Court’s evisceration of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 in Shelby County v. Holder.

Young lawyers must step forward and take the places of those marchers now lost or grown weary (gone are Durham, Bunkley, Hernandez, Bedford, and the Callejos). Only in this way does our journey toward justice continue.

Sol Villasana is Of Counsel with White & Wiggins, LLP. He may be reached at: svillasana@whitewiggins.com.

© 2014 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.