© 2015 The Texas Lawbook.

By Wyatt Dowling and Rob Ellis of Yetter Coleman

HOUSTON (July 23) “Phone metadata” has been in the news the past few years, mostly because of former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden’s leak of government documents that revealed a secret program involving bulk collection of telecommunications data on U.S. citizens.

But phone records are not just the stuff of espionage or criminal drug cases. Although limited, phone metadata can provide powerful evidence in civil litigation. It also involves unique hurdles in terms of obtaining this discovery, synthesizing the results, and overcoming challenges based on privacy.

Phone metadata is not the communications themselves – it’s who called whom, call date, time, duration, and other data. So how can it be useful?

One need only consider U.S. v. Apple, the price fixing case where the government accused Apple of conspiring with publishers to raise e-book prices. A core fact the government needed to prove its case was a horizontal agreement among publishers about pricing.

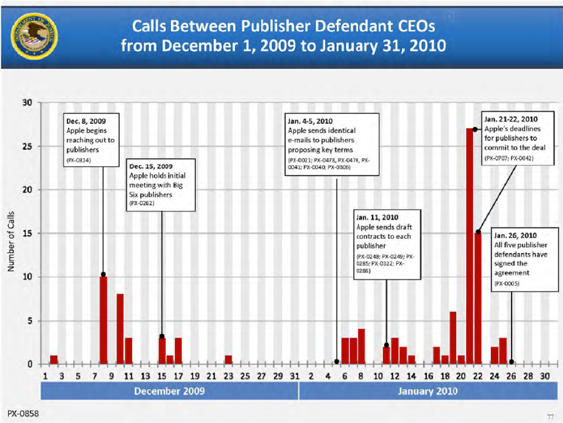

As the Second Circuit recently noted in its decision affirming the district court’s rulings in U.S. v. Apple, “[t]he district court found that the frequent telephone calls among the Publisher Defendants during the period of their negotiations with Apple ‘represented a departure from the ordinary pattern of calls among them.’” U.S. v. Apple, Inc., No. 13-3741-cv (L) (2d. Cir. 2015).

The government’s closing presentation used a simple and very effective bar chart to make the point, showing dates and the volume of calls:

The government didn’t have a transcript of the phone calls themselves, but it had powerful evidence of communication and coordination among key players at a key time – that is, highly probative circumstantial evidence of agreement among the publishers.

Most trial lawyers can see the appeal of phone records in conspiracy cases, but that is by no means their only use.

Consider a trade secrets misappropriation case, where the former employee was careful not to include incriminating details in written communications. But phone records may tell the tale. A flurry of calls or even one call of significant duration between the right individuals at the right time may be enough to persuade a jury that misappropriation occurred.

Consider a breach of fiduciary duty case where a group of directors blocks the company’s purchase of a property in order to acquire it themselves at a below-market price. Several phone calls to real estate appraisers or brokers can help show the plan was underway at the critical time. Phone records may also be used for impeachment. An executive who claims she was on vacation or out of the country at a time important to the case can be confronted with calls from her home or office, establishing that the facts are otherwise.

How do you obtain phone records?

This typically occurs through subpoenas on non-parties, particularly telephone companies. The first step is for outside counsel to obtain the telephone numbers and telecommunications providers associated with particular witnesses. This can be done through interrogatories, requests for admissions, or depositions.

In just a single case, one may need to serve multiple subpoenas on multiple telephone companies to capture call data from witnesses who may have multiple phones and providers. In addition to call data, most providers retain metadata on incoming and outgoing text messages.

Importantly, every telecommunications company has different procedures for obtaining phone records pursuant to a subpoena, different types of metadata that they retain, and different lengths of time that they retain this data. Some can take many months before producing any records.

The takeaway is that this is a process that outside counsel must initiate well in advance – i.e., several months at least – to ensure the data is available for depositions and trial.

Also, today “telecommunications companies” are not just landline and wireless phone providers like AT&T, Sprint, and Verizon.

Consider whether a witness uses video calls as well, through services provided by Facebook, Google, Skype, and others. Be aware that some of these providers may produce responsive records as a matter of routine, while others may be uncooperative to advance the privacy interests of their customers.

Finally, outside counsel should request a business records affidavit from the telecommunications company along with the subpoena, to ensure the records are admissible in evidence. Although there has been some narrowing of what qualifies as a “business record” under federal and state evidence rules, telephone records indisputably qualify.

What do you do with the phone records?

Be prepared for painstaking work by outside counsel to develop relevant facts from voluminous phone records, which often use cryptic codes that must be deciphered and are not user-friendly. Unlike run-of-the-mill email discovery, phone records will not identify the sender or recipient by name. Instead, the providers will most likely produce a long spreadsheet simply listing phone numbers called or texted at different times.

To make sense of this information, outside counsel and their staff will need to match up the numbers with actual people. The easiest way to identify numbers of key individuals is checking their signature block in emails already produced in discovery.

Also, several websites provide free or low-cost phone lookup services, such as www.intelius.com. For in-house counsel looking for ways not to add to discovery costs, this might seem like an avoidable expense. But setting out a targeted discovery plan at the outset that places limits on the hunt for incriminating calls can keep the costs manageable while increasing the prospects for discovering facts that can drive the litigation forward.

Almost as important as finding the information itself is time spent thinking about how outside counsel will present this raw data into a persuasive story. Bar charts and timelines can paint a picture of what occurred. Remember that sometimes the relevant point to highlight might be a conspicuous absence of communication or sudden change in behavior.

Finally, what challenges might you and your outside attorneys face in attempting to use call records?

First, one needs to have a clear story of relevance if the opposing side or a non-party moves for protection. Collecting phone records may impose burdens on the other side, and the court may be inclined to limit this type of discovery if it sounds like a fishing expedition.

Second, the more probative the evidence is, the more likely it is to be resisted. Requests should be carefully targeted to capture only the specific date ranges and witnesses whose communications you need. This should help overcome any claim by the other side that your requests are overbroad or burdensome, not to mention reduced discovery expenses in sorting through voluminous records.

Targeted requests should also help overcome any claim that production of such records violates the privacy rights of producing parties and their employees or attorney-client privilege. In general, phone call metadata does not implicate the right to privacy or privilege because the communication itself is not disclosed, only facts surrounding the communication.

Courts will also find less of an imposition if your outside counsel request these regularly maintained records from a major phone company, than if you ask the opposing party to produce this kind of detail from his or her own phone. Further, a protective order should alleviate any concerns about misuse of this evidence.

However, courts have broad discretion regarding discovery, and any discovery having to do with a person’s private calls will likely be subject to higher scrutiny. But if you and your outside counsel are able to overcome these hurdles and distill this evidence into simple and persuasive charts that tell the story behind the calls, the jury may reward you.

Wyatt Dowling and Rob Ellis are associates with Yetter Coleman LLP, a Houston litigation boutique that represents plaintiffs and defendants in high-stakes business and technology litigation involving the energy, technology and finance industries.

© 2015 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.