© 2017 The Texas Lawbook.

By Brent Walker of Aldous/Walker

The car cruised southeast on U.S. Highway 175 towards Kaufman. I was sitting in the back seat, my eyes closed, as I concentrated on our game. My mother, at the wheel, would ask the questions.

“The witness testifies that ‘Joe told me the car was speeding.’ What’s the objection?”

My older sister sat in the passenger seat, not wanting her elementary school-aged brother to get the answer before she did. “Hearsay!” we both would call out in near-unison before arguing about who said it first.

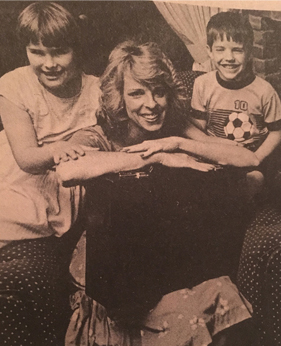

Playing a trivia game consisting of evidence objections is probably not a common thing to do with a 9- and 11-year-old. But for my sister and me, who were growing up just as my mother was growing into a career as a civil trial lawyer, that is one of the ways we would spend our time during our car trips. Whether to Cedar Creek Lake to visit my grandparents or running errands around town, we were talking law.

When my mother Diane Walker graduated from college in the early 1970’s, she first went into teaching, as that was one of the then-accepted career paths for women who worked outside the home, along with nursing and secretarial work. My mother was an excellent writer and a lover of the written word, so she taught English to high school students. While I can imagine she loved the subject matter, I suspect it was not challenging enough for someone of her prodigious intellect.

When my mother Diane Walker graduated from college in the early 1970’s, she first went into teaching, as that was one of the then-accepted career paths for women who worked outside the home, along with nursing and secretarial work. My mother was an excellent writer and a lover of the written word, so she taught English to high school students. While I can imagine she loved the subject matter, I suspect it was not challenging enough for someone of her prodigious intellect.

It was in the mid-1980s after my sister and I were born that my mother made the decision to go to Southern Methodist University law school. Some people spend their lives trying to find what they are supposed to be. It took my mother to her 30s. Thanks to her, I knew by the time I was 11 years old that I was going to be a trial lawyer because I saw how the practice of law can be extraordinarily rewarding to the soul.

In December 1986, 46-year-old Marine Corps veteran Ronnie Cox was working as an undercover police officer for the City of Addison. The City of Dallas Police Department was working jointly with the Addison PD to serve a narcotics warrant at an apartment in North Dallas. During the operation, communication broke down. Officer Cox had entered the apartment and was detaining a suspect at gunpoint. A Dallas Police officer stormed into the apartment, saw Officer Cox in plain clothes and holding a gun, and shot Officer Cox at least four times. For over 10 hours, Officer Cox endured immense pain before finally succumbing to his wounds.

My mother worked as part of the trial team representing the Cox family in a complicated federal §1983 civil rights case against the City of Dallas, along with the great trial lawyer R. Jack Ayres and the late gentleman Ed Wright. It was a high-profile case that was hotly disputed. There were television cameras at the courthouse and the City of Dallas had an extremely talented defense team.

As a young boy, I got to see the process unfold from up-close. I met the legendary pathologist Dr. Charles Petty, an expert for the plaintiffs, and learned about ballistics testing. My mother would tell me stories about the procedural fights that were had and sanction orders that the court issued.

More than anything, I learned just how hard one has to work to get a case ready for trial.

The jury deliberated for two days and came back with a verdict in favor of the Cox family, awarding over $2.3 million. At my age, I didn’t yet understand the meaning of the money awarded, but I did appreciate that the verdict had sent a message. What happened to Ronnie Cox should never have happened and it better not happen again.

It was justice. And my mother had helped obtain it. I knew from that point on, I was going to be a lawyer. I frankly do not know what else I could be in my life because I never imagined being anything else. Ultimately, both my sister and I followed in my mother’s footsteps to SMU law school and then to civil trial work.

I learned from my mother the love of the law and its capacity to make a positive impact on people and our community. One of the things you learn as the child of a civil trial lawyer is also that the practice of law is time-consuming and stressful, and requires sacrifice.

It wasn’t until I started working with my law partner Charla Aldous that I appreciated how hard that aspect of the practice must have been on my mother.

Like my mother, Charla was a single mom and attorney who had to find a way to do her cases justice while still fulfilling all of her parental obligations. Hearing Charla’s stories of struggle makes me appreciate more just how hard it must have been on my mother to juggle the conflicting demands on family and her practice. Looking back, I feel I can say that I never begrudged my mother working so hard, and I think that is because she made sure I understood what she was doing and the positive impact it would have.

One of the lessons my mother taught me when I was young was that the practice of law is like baking bread. When you put a bread ball in a pan, it will expand to fill whatever space you give to it. So too will the practice of law consume as much of your life that you give it, so you must set boundaries. That is a lesson that has always stuck with me and it is one I still struggle to apply in my practice today in trying to balance professional and family commitment.

But if my mother could help so many people and accomplish some amazing things as a lawyer, and yet also manage to instill a love of the law and justice in her two children, then I should be able to figure it out too.

Brent Walker is a name partner in Aldous\Walker in Dallas.

© 2017 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.