© 2017 The Texas Lawbook.

By Bruce Tomaso

(July 20) – “We asked this jury to speak to the world, and they have done that.”

With those words 20 years ago, Windle Turley summed up one of the most stunning, far-reaching verdicts in Texas history.

On July 24, 1997, a jury in the 134th Civil District Court in Dallas County awarded $119.6 million to 10 young men who had been repeatedly molested as children by Rudy Kos, a Roman Catholic priest. (An 11th plaintiff was the family of a victim of Kos’ who had killed himself before trial at the age of 21.)

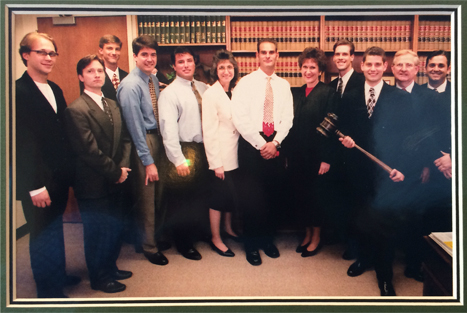

Ten of the 11 young men were former altar boys. Turley represented eight of the plaintiffs; a protégé of his, Sylvia Demarest, represented the other three.

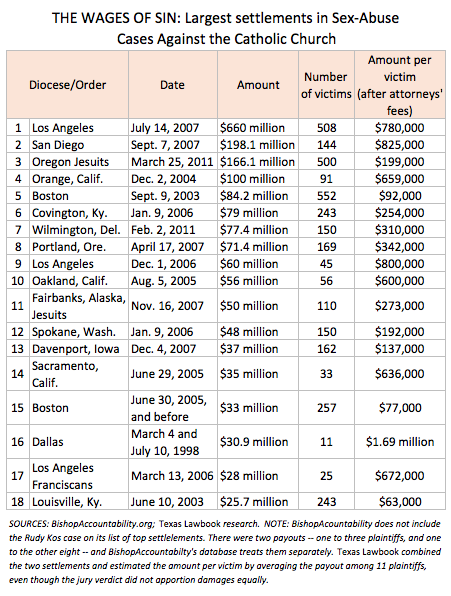

At the time, the verdict was the largest ever in a case of sexual abuse by the Catholic clergy. (With compound interest dating back to filing of the suit, the total owed approached $145 million – one-seventh of $1 billion.) That record, however, would soon be eclipsed many times over – in large part because the Kos case helped trigger an avalanche of similar claims against priests across the country.

Kos, by then stripped of his priestly duties, was living in San Diego and working occasionally as a paralegal. He never answered the lawsuit and never appeared in the courtroom of Judge Anne Ashby, who entered a default judgment against him.

That left the Diocese of Dallas as the sole target of the jury’s judgment, and its wrath.

“This case opened the door,” Turley said in an interview last month. “One result of the Kos verdict was a real empowerment of victims. It convinced them, as well as a substantial group of attorneys for victims, that they could make a difference.”

The Kos case shook the Catholic Church to its foundations. Randal Mathis, the attorney for the Dallas diocese, acknowledged as much when he told the jurors, even while vowing an appeal, “There’s absolutely no doubt the diocese received your message very, very clearly.”

Mathis, who continued to represent the diocese until 2011, said in an interview: “I have a great deal of respect for what the jury did, what it was charged with doing, and what it tried to do in this case.”

He added: “From their verdict, it was clear that the jury had very strong feelings. The diocese understood that. We all understood that.”

Mathis nonetheless praised Charles Grahmann, the Catholic bishop of Dallas from 1990 to 2007, for taking decisive steps to remove Kos and, throughout the bishop’s tenure, “to try to ensure that there was minimal risk of something like this ever happening again.”

As he did at trial, Mathis contended that the diocese was deceived for years by Kos, “a sociopath.”

Far beyond punishing one priestly pervert, however, the jurors decreed that the church itself had sinned. They unanimously found the Dallas diocese grossly negligent, not only for failing to heed years of clear warnings about Kos, but also for engaging in fraud and conspiracy to hide his crimes from the public from law enforcement and even from his parishioners. (The diocese, claiming the jury’s judgment would plunge it into bankruptcy, eventually settled with the plaintiffs for $30.9 million.)

By 2002, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, no longer able to deny the breadth of sexual abuse by priests or the complicity of the church’s hierarchy in concealing that abuse, convened a special meeting in Dallas and enacted major reforms intended to ensure the safety of youngsters in Catholic parishes and parochial schools.

“Because the Kos case got so much attention – not only in the United States, but globally – it put the bishops’ conference in a position where it had to do something,” Demarest said in an interview last month.

“The Kos verdict finally made it clear to the bishops that sexual abuse by the clergy could no longer be ignored. And it couldn’t be covered up. The clear message in the jury’s verdict was that the diocese had a moral and a legal duty to stop priests like Rudy Kos from preying on children.”

On the day of the jury’s verdict, Demarest was more pointed: “I hope they wake up the pope tonight with this,” she said.

“Ninety percent of the time,” Turley is fond of saying, “the outcome of a trial is determined by the end of opening statements. By then, I think, the jury has usually made up its mind.”

His opening statement in the Kos case was a textbook example – literally. It formed the basis for a chapter, “Connect with Jurors,” in Turning Points at Trial, a legal textbook by Shane Read, a Dallas lawyer and author.

“These young men believed their church, believed their priest,” Turley told the jurors. And Kos “reached out and grabbed those kids and preyed on them like a vulture.”

He added, “The most beautiful years in their life were taken from them.”

He added, “The most beautiful years in their life were taken from them.”

As a young man, Turley entertained thoughts of becoming a Methodist preacher. He enrolled in a seminary after college, before turning to law.

There’s more than a hint of the small-town parson in his gentlemanly, avuncular manner. He addressed the Kos jurors in a calm, quiet voice, even as he described in horrifying detail Kos’s predation.

“He would massage their feet until they were comfortable, and their feet, with their socks on, would be in his crotch. And pretty soon the socks would be off.… And after they became more comfortable with this, finally, he would be masturbating himself regularly with their bare feet, first through clothes and then with his penis out. And then after a few months or years of this, and they seemed to experience this perhaps with less terror, Kos entered into oral sex on almost all of them.…”

The priest, he said, would sometimes give his young victims liquor and drugs – Valium and marijuana, among others – before assaulting them. As a result, Turley told the jurors, “Some of these young men today suffer serious chemical addiction problems.”

One plaintiff, “after he had passed out from the consumption of alcohol and drugs, went home with a bloody rectum. This was not casual fondling.”

The diocese didn’t dispute the awful allegations against Kos, who would later be convicted in a criminal court and sent to prison for life.

Rather, the diocese’s defense was that Kos had duped his superiors, that for years they were clueless about his evil deeds. Mathis, the defense lawyer, said it wasn’t until 1992, shortly before Turley and Demarest filed their suit, that Bishop Grahmann and his lieutenants obtained proof of Kos’s transgressions. As soon as they did, the lawyer said, they moved to suspend the wayward priest.

“Now do we, as a diocese, have egg on our face today?” Mathis said in his opening statement. “You bet we do. You bet. There isn’t any doubt about it.”

Kos was essentially a defendant without assets. The plaintiffs’ case against the diocese, with its deep pockets, rested on piercing the “we-had-no-idea” defense.

Turley told the jury in his opening statement that there were numerous “red flags” over the years, events that should have alerted church officials to Kos’ offenses. Then, through the course of the 14-week trial, as he and Demarest presented evidence of each such event, they would affix a small red flag to a display board.

By the end of the trial, there was lots of red on that board:

• Unlike most men called to the vocation, Kos didn’t enter the priesthood until he was in his 30s. He was married, and so, before he could enter the seminary, he had to have his marriage annulled. His wife told a diocesan tribunal that their five-year marriage had never been consummated. “Rudy is gay, and he has problems with boys,” she said. She added that she kicked him out after finding a stash of love letters from teenage boys.

• When Kos applied for admission to Holy Trinity Seminary in Irving, the rector turned him down, writing in April 1976, “There is a certain amount of instability here I do not like.” The following spring, a new rector reversed that decision and let Kos in.

• Just before Kos’ graduation, a former seminarian said Kos hit on him in the seminary’s swimming pool. A month after this was reported to the diocese, Kos was ordained into the priesthood.

• In 1986, the pastor of St. Luke Catholic Church in Irving, where Kos was assistant pastor, wrote to warn diocesan officials that young boys were routinely spending the night in Kos’ room in the rectory.

• In 1992, the associate pastor at St. John Nepomucene Catholic Church in Ennis, where Kos was the pastor, sent a 12-page letter to diocesan headquarters, complaining about Kos’ improper behavior with boys. The diocese warned Kos, saying, “Your conduct is imprudent. It could jeopardize the diocese.” He was not removed from the ministry. When Kos was later sent to a psychiatric center in New Mexico, parishioners at St. John were told their pastor was being voluntarily treated for stress.

“The church hates scandal. Hates scandal,” Turley said when interviewed. “The church, up to the point of the Kos case, just simply would not face up to the facts that this scandal was going on. I was surprised by the magnitude of it, and by the depth of their denial.”

* * *

By all accounts, Bishop Grahmann’s trial testimony proved to be disastrous for the defense. The bishop came across as evasive, haughty and remote. (Grahmann, who stepped down in 2007, having reached the mandatory retirement age of 75, did not answer a request – submitted through Mathis, the diocese’s attorney in the Kos case – for comment for this article. Grahmann’s consistent practice as bishop was not to respond to press inquiries about the clergy sex scandal.)

On the witness stand, Grahmann said he’d never so much as glanced at Kos’ personnel file, which included, among other “red flags,” letters from two priests who tried to warn the diocese that Kos was having boys spend the night with him. Grahmann said that having turned the matter over to an underling to look into, “there was no reason for me to look in the file.”

Demarest recalled deposing Grahmann and asking him to whom he was accountable. His response: “Only to God.”

“I asked him that question because I thought his answer might give us an idea of what kind of witness he’d make at trial,” she said.

“And it did. He was a terrible witness. He was aloof and arrogant and completely unapologetic.

“He was incapable of acknowledging that he’d done anything wrong in the way the whole Kos thing was handled. Yet our evidence clearly showed – and the jury agreed – that there’d been warning signs for years. The diocese simply ignored them.”

There was, for example, this exchange during cross-examination by Demarest:

Q. Are you aware of the fact that Father Kos abused altar boys at All Saints Church the entire time he was there?

A. No, I’m not aware of that.

Q. That he did this on church property?

A. I’m not aware of it.

Q. Are you aware of the fact that Father Kos abused altar boys at St. Luke’s in Irving?

A. I’m not aware of that.

Q. And that he did it on church property?

A. No.

Q. Are you aware of the fact that Father Kos abused altar boys in St. John’s in Ennis and that he did that on church property?

A. No, I’m not aware of that.

Q. Are you aware, from his testimony, that Father Kos got boys drunk –

A. No, I’m not aware of that.

Q. – in his room at the rectory at All Saints, St. Luke’s and St. John’s; are you aware of that?

A. I’m not aware of that.

Q. That he gave them drugs on church property at All Saints, St. Luke’s and St. John’s; are you aware of that?

A. I’m not aware of that.

Q. Now, Bishop Grahmann, would you agree with me that a priest has a great deal of access to young children through his ministry?

A. Yes and no.

And this one, in which the bishop split hairs over whether it was OK for priests to sleep with children:

Q. Isn’t it reasonable, Bishop Grahmann, given the information that the dioceses had at that time, for them to at least know that it was not a good practice for a priest to take a little boy into his bedroom, close the door and spend the night with him? Can’t we at least say that?

A. Possibly.

Q. Can’t we say that probably?

A. Possibly.

Q. We can possibly say that probably?

A. Probably possibly.

When interviewed, Mathis, the defense lawyer, attributed Grahmann’s performance on the stand to the stress of testifying in such an emotionally charged case, before a standing-room-only crowd of spectators, under pointed cross-examination from the plaintiffs’ lawyers.

“He was nervous,” Mathis said. “As a result, his trial testimony became somewhat confused. That left some misimpressions.”

Whatever their cause, Grahmann’s evasiveness and lack of candor weren’t lost on the jurors – 10 women and two men, including two self-described “former” Catholics.

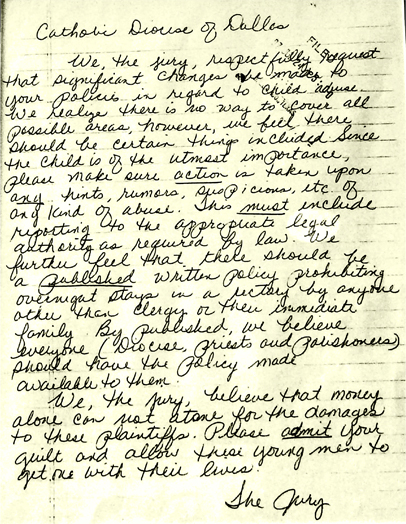

In an extraordinary move, the jurors wrote a letter to the diocese, which they asked Judge Ashby to read in open court after their verdict was rendered. The letter urged church leaders to change their policies on dealing with reports of child abuse. And it urged them to change their ways.

“Please admit your guilt,” it said, “and allow these young men to get on with their lives.”

* * *

In another extraordinary move, Judge Ashby addressed the plaintiffs and defendants in a heartfelt speech after closing arguments.

Outside the presence of the jury, Ashby slipped off her judicial robe, took a seat in the jury box and poured out her heart about what she’d heard during the trial. (Ashby was at first unaware that a reporter for The Dallas Morning News was in the courtroom. She tried, unsuccessfully, to dissuade the reporter from writing about her comments.)

The judge told the plaintiffs, “Everybody in this courtroom has been grieving.… You’ve been horrified. You’ve been hurt. You’ve been miserable. I’ve been so close to your tragedy it just breaks my heart.”

She went on: “Each and every one of you is a valuable member of this community. I know that your church and your God is very, very important to you. Don’t give it up.”

Of the abuse victim who had died by suicide, she said: “I wish I could wave my magic wand and bring that wonderful young man back here. But I can’t.”

Then, turning to the diocesan officials seated at the defense table, she said: “The church has many wonderful things ahead of it,”

In an interview with the Texas Lawbook, Ashby, now a prominent mediator and arbitrator, said her unconventional commentary, cited at the time by the defense as evidence of bias toward the plaintiffs, was intended to convey her sympathy to both sides.

“The trial was a very emotional experience for everyone involved,” she said. “I felt a great deal of sympathy for these young men, but also for the church. And I’d been on the bench long enough by then to know that I had to separate any feelings I had from my rulings.

“It was just a really rough time for everybody.”

* * *

Five years after the Kos verdict, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops met in Dallas and adopted a sweeping “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People.” It required dioceses to report allegations of sexual abuse to public authorities; to cooperate in investigations by those authorities; and to remove pedophile priests from duty. It required church employees, including priests, to undergo “safe environment” training and criminal background checks.

Significantly, the charter prohibited confidential settlements of complaints against the church, except in rare cases where the victim had “grave and substantial reasons” to maintain secrecy. The decades-old practice of hiding such settlements under court seal was central to the storyline in Spotlight, the Oscar-winning 2015 movie about The Boston Globe’s uncovering of a massive coverup of sexual abuse by Catholic priests in the Archdiocese of Boston.

Turley said the church’s abandonment of secret settlements was a direct outgrowth of the Kos lawsuit.

“Until our case,” he said, “virtually all sex-abuse complaints against the Catholic Church resulted in settlements placed under seal by confidential agreement. Consequently, the public had no idea what was going on.

“We refused from the very start to negotiate a secret settlement. We said we wouldn’t do it. Secret settlements are bad for the public. They’re bad for society.”

* * *

So, 20 years later, how much has changed?

Not as much as Sylvia Demarest might have hoped.

“I think sexual abuse by priests is still going on – all over the world,” she said.

“When you look at all the money the Catholic Church has paid out in settlements and in legal fees, it’s a fortune. To say nothing of what all the negative publicity has cost them. So there’s still a motivation to cover up misconduct by priests whenever they think they can get away with it. That continues, and it will always continue.”

She added: “I suspect that the problem is much worse in a lot of other countries than it is here. Not every country has the statutory support for victims that we have. Not every country has rules in place to make civil remedies accessible. And in many places, especially poorer, rural countries, the parish priest is still treated like a saint – or God.

“Under those circumstances, there are strong disincentives to victims coming forward.”

Demarest said that despite the settlements that made them millionaires, the plaintiffs in the Kos case weren’t all successful in their efforts to get on with their lives.

Today, one of her clients is a well-to-do entrepreneur who built and manages a diverse portfolio of successful business interests in the Dallas area. (Like the other plaintiffs who could be reached, he declined to be interviewed for this article.)

But another of her clients died this year in his mid-40s, losing what Demarest called a lifelong battle against the demons of drugs and alcohol. She’s convinced that his addictions were rooted in what Kos did to him.

The most recent annual audit completed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops was released in May of this year. It found that survivors of child sex abuse had come forward with 1,318 new allegations against Catholic clergy between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016. That was more than in either of the previous two years.

Most of these new charges were “historical,” the audit said, meaning they were new revelations of old instances of abuse. But, disturbingly, “there were 25 allegations reported in this year’s audit involving current minors.”

The message of that was not lost on the bishops.

While the church “has made great progress,” the audit said, “there is still work to be done.…

“We cannot become complacent. We must be ever vigilant in our parishes and schools.”

© 2017 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.