The Dallas corporate law firm Gardere would have celebrated its 110th anniversary this year. Andrews Kurth of Houston would have been 117 years old. Strasburger & Price would have turned 80.

The three old-line Texas corporate law firms combined employed nearly 1,000 attorneys at their peak earlier this decade and generated more than $600 million in revenues. They were staples of the Dallas, Houston and Austin business communities and represented some of the largest companies in the state.

As the past-tense verbs indicate, the three no longer exist as independent law firms.

Each one merged with a larger national law firm in April 2018. Fifteen months later, leaders at all three say their marriages have gone better than they expected.

“By nearly all measurements, all three law firms are better off today post their mergers than they were before the mergers,” legal industry consultant Kent Zimmermann said. “To size up the success of a deal, you need to examine the alternatives to not doing the deal. Were there alternatives to reaching the firms’ objectives?

“Each one of these firms took a different path to get to this place and had different needs and reasons to do their mergers,” he said.

Andrews Kurth, Gardere and Strasburger counted banks, insurance providers, oil and gas companies and commercial real estate owners and developers as clients. For decades, lawyers joined these firms right out of law school and never left.

Their attorneys included influential leaders, such as former Secretary of State James Baker III and former U.S. Trade Ambassador and Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk. Partners at the firms earned seven-digit incomes. Life was good.

Then, it all changed.

Tort reform hurt litigation, especially insurance defense work. Large, deep-pocketed national law firms – long walled off from operating in Texas – invaded the state. They raided the ranks of these three and other firms, stealing their finest lawyers who had the best clients and generated the most revenues.

The result: The three firms witnessed declining revenues from 2015 to 2018.

Many legal industry analysts predicted as far back as 2015 that Andrews Kurth, Gardere and Strasburger could no longer compete at the same level as their elite corporate law competitors who had deeper benches and, more importantly, deeper pockets.

All three firms were, however, determined to remain independent. Each rejected multiple proposals to merge. Even so, revenue declines continued.

“All three of these firms faced uncertain futures,” Zimmermann said. “They could remain independent and watch their positions in the marketplace continue to deteriorate, or they could do a merger.”

Consultants were hired. Strategic plans were developed. Options were studied and debated.

“These were huge and difficult decisions we were making that impacted the lives of hundreds of people and our clients,” Holly O’Neil, former managing partner at Gardere who negotiated the merger with Milwaukee-headquartered Foley & Lardner, told The Texas Lawbook.

Then, in April 2018, the stars aligned, as within days of each other the trio of firms did the one thing that they once swore they would never do: They merged with larger out-of-state legal operations.

“True, we rejected many offers over many years to merge,” said former Strasburger managing partner Dan Butcher, who helped engineer the deal with Detroit-based Clark Hill. “Making the decision to merge was certainly one of the toughest and most important in the firm’s great history.”

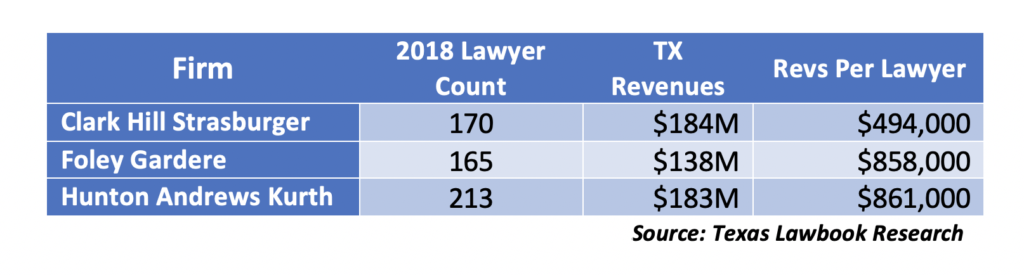

Today, leaders at Foley Gardere, Hunton Andrews Kurth and Clark Hill Strasburger say their year-old combinations have been successses and that the lawyers at their firms are representing more new clients, billing more hours and making more money they did before the mergers.

Initial data appear to support the claims – or at least show that their previous declines have halted and that they are headed in the right direction.

All three firms witnessed another year of declining revenues in 2018, but analysts say this is mostly the result of each losing partners and associates who didn’t want to be part of the newly merged legal operations. The firms also incurred various one-time merger expenses – from combining databases and billing systems to terminating lease agreements and significantly increased travel costs as lawyers from the merging firms made extra efforts to get to know each other better. For Foley Gardere and Hunton AK, those expenses were about $9 million each.

“We had a great year,” said Hunton AK’s deputy managing partner Robin Russell. “We exceeded our profit budget by 4%. We integrated faster than anyone anticipated. We’ve added new clients and expanded relationships with existing clients.”

O’Neil and Butcher echo Russell’s position.

Foley Gardere

“It has been a whirlwind – can’t believe it has already been more than a year,” O’Neil said. “We are already reaping the fruits of our labor regarding revenues, generating new business and attracting lateral hires. It’s been an exhilarating year.”

Foley Gardere implemented a program the day of the merger called “But For,” which measures achievements that would not have happened “but for” the merger.

Because of the merger, lawyers at Foley Gardere worked on 125 new matters that billed 15,000 hours and generated more than $10 million during the first 12 months of the combined firms – all of which is directly attributed to the merger.

In addition, the firm reports that legacy Gardere lawyers worked on scores of matters for existing Foley clients and legacy Foley lawyers did the same for existing Gardere clients – a total that accounted for more than 40,000 hours billed during the first year of the merger.

“We had all the synergies on paper, but you never know until you take action,” O’Neil said. “Legacy Gardere has definitely benefited from the strong organizational structure and larger platform that Foley had in place.”

Foley Gardere lost about two-dozen lawyers in Texas as a result of the merger – going from 185 to 165 attorneys during the past year.

But revenue per lawyer jumped from $745,000 in 2017 to $858,000 last year.

“We anticipated we would be flat or even down a bit in revenues for the first year, but we had a better year than we expected,” Foley Chairman Jay Rothman said. “The biggest challenge was the lawyers at the two firms getting to know each other. They need the time together to develop the knowledge and trust.”

Zimmermann, who advised Gardere and Andrews Kurth, said Gardere went into merger discussions with a “well-defined strategy” and faced less stress points than Andrews Kurth and Strasburger.

“Gardere wanted to grow in the Northeast and Chicago but didn’t think it would be a good fit for a northeastern law firm,” he said. “They wanted a culture without sharp elbows and partners who were willing to share work across the firm.”

Hunton Andrews Kurth

Andrews Kurth had strong M&A and capital markets practices in Houston and Dallas before the merger. The firm had 255 lawyers in its Texas offices in 2016 and revenues from those attorneys exceeded $250 million.

Between 2011 and 2017, AK lawyers represented 207 businesses involved in mergers and acquisitions that had a combined value of more than $200 billion, according to Mergermarket, a global research firm. Acritas, a publication that surveys corporate general counsel, ranked AK as having one of the five best law firm brands in Texas.

Top national law firms seeking to expand into Texas, such as Winston & Strawn and Orrick, approached AK leaders about potential mergers. AK rejected all such offers.

“AK had an aspiration to grow the firm because they understood the importance of scale,” Zimmermann said. “The national firms wanted a merger, but they didn’t want all AK lawyers to be part of it and AK leaders didn’t want a whole chunk of its partners left behind.”

By Dec. 31, 2017, Andrews Kurth’s lawyer headcount in its Texas offices had dropped to 204 attorneys and revenue declined to $206 million.

AK leaders engaged in merger talks in late 2017 with Virginia-based Hunton & Williams, which had more than 80 lawyers in Texas and generated an estimated $70 million in revenues from its attorneys in Dallas, Houston and Austin.

The combined Hunton Andrews Kurth has 213 lawyers in Texas and more than 850 attorneys worldwide. Total revenues in 2018 hit $748 million – about $183 million of which was generated from the firm’s Texas offices.

Russell, who specializes in corporate restructurings and finance, said that lawyers from legacy AK and legacy Hunton have worked together on more than 700 matters for clients since the merger.

For example, lawyers from legacy Andrews Kurth’s public finance group worked with the real estate team from Hunton on the financing of the New York Islanders sports stadium. AK and Hunton teams worked together in representing private equity firm Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners in its $3.6 billion acquisition of Oryx Midstream this past spring.

“Our capabilities to serve our clients have definitely been enhanced by the merger,” Russell said. “We have a footprint that has been expanded geographically and in terms of expertise. For example, AK clients have benefited from legacy Hunton’s premiere cybersecurity practice.

“We have had so much energy and momentum this past year,” she said. “The challenge is to keep that up and to capture all the opportunities offered by the merger.”

Clark Hill Strasburger

If legal industry analysts thought Andrews Kurth waited two years too long to merge, the general belief is that Strasburger was two decades late to make such a move.

“We made a decision to remain a Texas-based firm,” Butcher said. “We were happy being Strasburger. We were satisfied with lawyers who didn’t charge clients outrageously high hourly rates.”

Strasburger was the source of dozens of great trial lawyers now at law firms across Texas, including Weil Gotshal litigation partner Paul Genender and U.S. District Judge Karen Gren Scholer.

In 2016, Strasburger was the 10th largest law firm in Texas by headcount with 196 attorneys operating in the state. By revenues, the Dallas-based firm ranked 18th in 2016 with $93 million. But the firm’s revenues per lawyer were $486,000 – nearly half of Andrews Kurth – and didn’t even rank in the top 50.

Butcher said firm leaders changed their minds during the past few years as more regional law firms started entering the Texas market.

“The regional firms have similar rates, and that made us rethink our feeling that we should look to expand outside of Texas,” Butcher said.

Clark Hill, he said, was the best fit for Strasburger.

“We expected the merger with Clark Hill would improve our ability to serve clients outside of Texas, but it also has helped increase what we can do for clients in Texas,” Butcher said. “Both legacy Strasburger and legacy Clark Hill have seen an increase in revenue directly as a result of the combination.

“Just today, I had a long-time client ask if we could help them with a Pennsylvania tax issue,” he said. “Before the merger, we could not have handled it. Now, we can.”

As a result, revenue per lawyer is up nearly 10% and the firm is seeing increased interest from lawyers at competing operations.

Clark Hill Strasburger has more than 640 lawyers throughout the U.S. and its 2018 revenues jumped 53% to $295.9 million. Net income increased by 72% to $65.8 million.

Butcher said the firm is only starting to discover potential areas of growth.

“We haven’t done a good enough job of promoting the Clark Hill name and expertise in Texas,” he said. “We need to do better in helping our own lawyers in Texas know all of the capabilities of the firm so we can serve our clients better.”

Leaders at Clark Hill Strasburger, Foley Gardere and Hunton AK say that the cultures of the legacy Texas firms have remained as they were prior to the mergers.

“Having a ‘great culture’ is something that gets tossed around a lot without any true context,” said Butcher, noting that Clark Hill has been ranked as one of the top 100 best places to work in the country.

“Clark Hill’s culture was demonstrated to us well before our combination. In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Strasburger & Price conducted an internal fund drive to help the members of our team in Houston and Beaumont with uninsured losses from the hurricane,” Butcher said. “Even though we were not a combined firm at that time, and without any ask by us, Clark Hill also conducted an internal fund drive and raised a substantial amount to add to the funds raised by Strasburger employees.

“That really showed us a lot about the culture and people of Clark Hill,” he said.