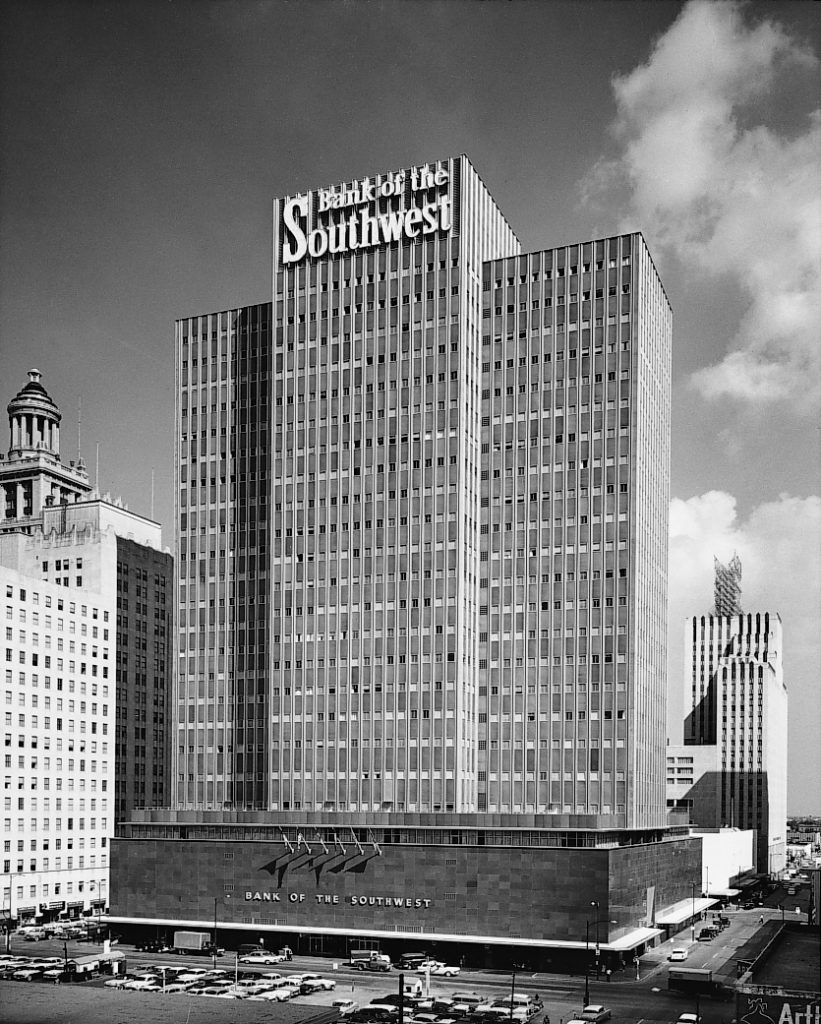

Houston corporate lawyer John Freeman stared at a massive hole in the floor outside his eighth-floor office in the Bank of the Southwest Building at 919 Milam Street in downtown Houston.

As the fourth lawyer to join Fulbright & Jaworski in 1923, Freeman had witnessed extraordinary growth at his firm, which had reached 60 attorneys in 1960. The firm decided to construct a staircase to expand to the floor below to add a couple dozen more lawyers in the years to come.

“Mr. Hall, where will it ever end?” Freeman asked Charles Hall, a rookie tax lawyer who joined the firm in 1957. “Where will it ever end?”

Six decades after that conversation, Hall – now senior counsel who has practiced at the firm for 62 years – concedes it “didn’t stop there” and even now there’s no hint that the end of the firm’s growth is anywhere in sight.

See Also:

Carol Dugan: The Past and Present Future

Fulbright at 100: A Time Line

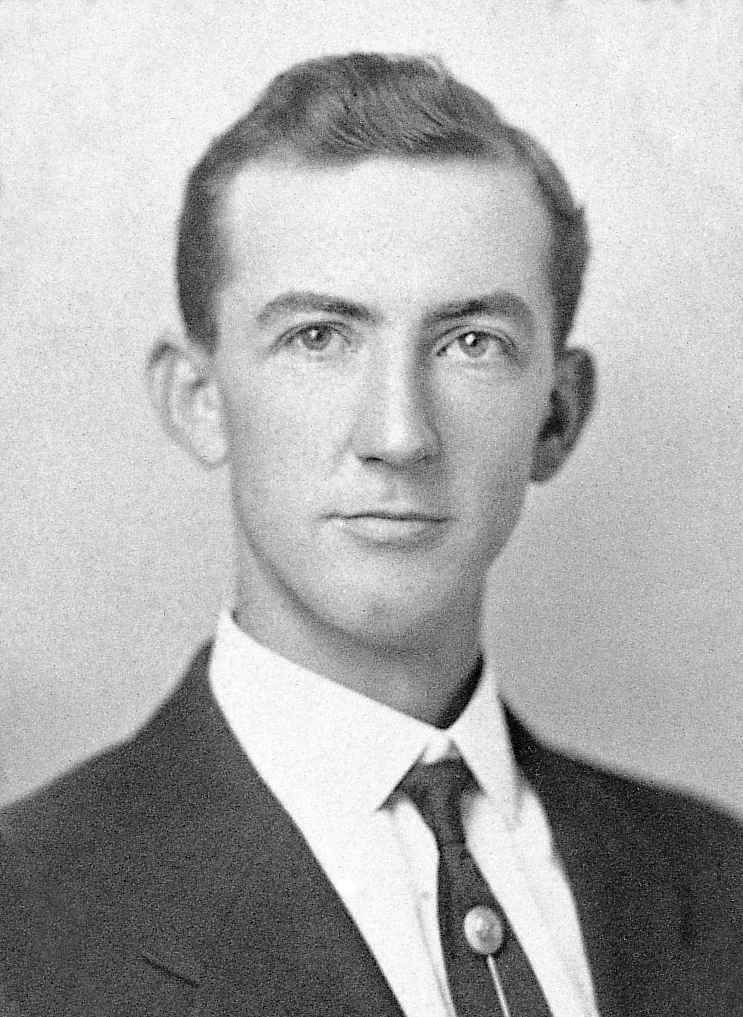

Exactly a century ago, Rufus Clarence Fulbright and John H. Crooker started their own business law firm in Houston. A couple years later, Freeman and a handful of other prominent lawyers had joined. The firm added a young, strong-headed trial lawyer in 1931 named Leon Jaworski, who decades later became widely revered as a god in the legal profession and described by the American Bar Association as “one of the most heralded trial lawyers of the millennial.”

Today, Norton Rose Fulbright – the product of Fulbright & Jaworski’s 2013 merger with London-based Norton Rose – occupies 11 floors atop the Fulbright Tower in downtown Houston. The firm boasts more than 4,000 lawyers in 29 countries, including 411 attorneys in Texas and 820 across the U.S. Global revenues are expected to top $2 billion this year.

“When you look back at the history of the firm, to think that two guys getting together in Houston in the fall of 1919, and 100 years later, that having grown to 4,000 lawyers is amazing,” says Jim Repass, a partner in Norton Rose Fulbright’s intellectual property law practice and the firm’s unofficial historian.

No Texas corporate law firm has had a bigger historical impact on the legal profession, business and politics than Fulbright.

The firm’s lawyers are directly responsible for the creation of the Texas Medical Center, the M.D. Anderson Foundation, the University of Houston and the Houston Bar Foundation, which provides legal services to thousands of Texans annually.

Fulbright attorneys prosecuted war criminals, helped Texas Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson defend his U.S. Senate seat while also running for vice president, saved Texaco from bankruptcy liquidation and, of course, led the Watergate investigation and prosecution of President Richard Nixon and nearly two-dozen of his appointees.

The firm’s clients include ExxonMobil, LyondellBasell, Energy Transfer Partners, Shell Oil and NuStar Energy. The firm is currently representing milk producer Dean Foods in its bankruptcy and recently advised BDT Capital Partners in its acquisition of Whataburger.

Corporate lawyers for Fulbright have represented Texas companies involved in 426 mergers, acquisitions and joint ventures with a combined value of $116.2 billion since 2007, according to the independent research firm Mergermarket, which provides M&A data exclusively to The Texas Lawbook.

But high-stakes litigation has always been Fulbright’s bread and butter. More than a half-dozen federal judges in Texas are Fulbright alumni. Houston trial lawyer greats David Beck, Steve Susman and the late Joe Jamail (who died in 2015) earned their courtroom spurs during their early years at the firm.

“Fulbright has been known nationally for a history of excellence in litigation for a long time,” says law firm consultant Kent Zimmermann. “This is a law firm with a great history but a firm that has successfully grown beyond its roots.

“Norton Rose Fulbright is now known as one of the great global law firms, and that is no small feat,” Zimmermann says.

Zimmermann and other legal industry analysts say that Fulbright, like most Texas-based law firms, has faced numerous business challenges.

For example, the firm’s competitive strength – the size and depth of its litigation practice – actually became a problem 15 years ago when the Texas Legislature enacted massive tort reform measures that dramatically reduced the amount of high-stakes litigation in the state.

Then eight years ago, more than a dozen elite national corporate firms opened offices in Houston and Dallas and stole scores of experienced corporate transactional lawyers away from Texas-based firms, including several at Fulbright, by paying them guaranteed seven-digit salaries.

As a consequence, revenues declined or remained stagnate for several years.

By combining with Norton Rose, leaders in the firm’s Texas offices shifted strategies. They abandoned most of the lower-paying insurance defense work in favor of toxic tort and complex commercial litigation for companies in the energy industry.

And there was a concerted effort to grow and compete globally.

Legacy Fulbright grew three ways: recruiting law students, lateral hiring from competitor law firms and through mergers with other practices.

“We merged with Chadbourne & Parke [in 2017] which was 125 years old. I remember being in meetings with Norton Rose and I said to them very proudly that we were over 95 years old,” says Gerry Pecht, now the head of global litigation for Norton Rose Fulbright. “And they said, ‘We were formed in 1794.’

“These are law firms that have been around for a very long time,” Pecht says. “The fact that these law firms that have great longevity and great ability to last through ups and downs and vagaries of the economy, that they would come together to form this one law firm and do so for the common good – I find it absolutely amazing.”

The result has been noticeable financial success.

Norton Rose Fulbright’s revenues per lawyer, which experts say is the best and most reliable financial measurement, jumped from $795,000 in 2017 to $870,000 last year.

Norton Rose Fulbright is the second largest law firm in Texas by lawyer headcount and the third largest by revenue. The firm’s lawyers in Texas generated $342 million in revenues in 2018 – a 5% increase from 2017, according to Texas Lawbook research.

Repass was in South Africa four years ago when a client offered to drive him by the law firm’s offices in Johannesburg after dinner.

“Across the top of the [11-story] building was Norton Rose Fulbright,” Repass says. “I bet when Clarence Fulbright started this law firm in 1919, he probably didn’t have the thought that his name would be on the side of a building in South Africa. The growth has been amazing.”

The Beginning

R.C. Fulbright was a 38-year-old corporate lawyer and Baylor University graduate born and raised in Northeast Texas. He taught Sunday school and represented cotton traders in business transactions and before regulatory agencies.

John Crooker Sr. had very little formal education and, like Abraham Lincoln, was self-taught about the law. He was mentored by a couple of licensed lawyers and did what many old-time lawyers did – “read law,” meaning he was licensed to practice in 1911 without actually attending law school.

Crooker worked at the Harris County District Attorney’s office with James A. Elkins, one of the founders of Vinson & Elkins. Fulbright, who was considered an “an outstanding citizen, a fine lawyer but not a very good golfer,” practiced at Andrews, Ball and Streetman, which is now Hunton Andrews Kurth.

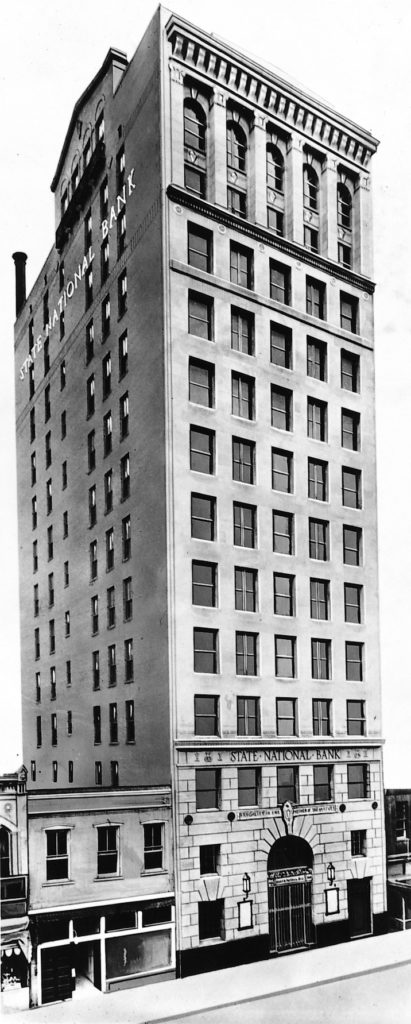

But in the fall of 1919, when William Hobby was governor of Texas and when Congress approved the Nineteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution giving women the right to vote, Fulbright and Crooker opened their new office in the Union National Bank Building, where they officed for five years.

Crooker was the trial lawyer, while Fulbright represented Anderson, Clayton and Company, the world’s largest cotton trader co-owned by Monroe D. Anderson. Yes, that M.D. Anderson.

Fulbright’s representation of Anderson, Clayton, the Texas Company (later known as Texaco), the Magnolia Petroleum Co. (later known as Mobil Oil), major Texas ports and the Houston Chamber of Commerce meant that he frequently traveled to Washington, D.C. to represent the cotton trader before the Interstate Commerce Commission.

In 1927, Fulbright officially moved to the Nation’s Capital and opened the firm’s first office outside of Houston.

“Mr. Fulbright was known as a wheeler-dealer, and if he had lived longer, we might have had the biggest law office in Washington, D.C.,” says Hall, who points out that Fulbright died in 1940 at the age of 58.

When the stock market crashed in 1929 and the Great Depression hit the economy, most law firms suffered, too. Fulbright, however, thrived as the firm saw its billable hours grow by representing banks and creditors in various bankruptcies and collection efforts.

“During various economic slumps, it has been evident that previously busy persons who now have time to spare find it both possible and desirable to litigate matters that probably would have been resolved by negotiations in busier times,” according to a history of the firm published in 1994 called Fulbright & Jaworski. “Hard times spawn lawsuits.”

Zimmerman says that all law firms face periods of distress. “The great law firms know that they are stumbling or facing tough times and get aggressive in fixing the problems,” he says.

Fulbright and Crooker billed corporate clients at a top rate ranging from $20 to $30 an hour in those early years. Today, top partners at Norton Rose Fulbright in Texas charge $1,000 or more per hour, according to Texas Lawbook research.

M.D. Anderson died in 1939, leaving his $19 million estate to his foundation, which had two trustees – Freeman and fellow Fulbright partner William Bates, who was a renowned raccoon hunter.

In 1941, the Texas Legislature budgeted $500,000 for the construction of a cancer research hospital in the state. Freeman and Bates convinced officials at the University of Texas to build the hospital in Houston and agreed to match the state’s funding with $500,000 from the foundation under one condition: that the hospital be named after their client, M.D. Anderson.

Enter Leon Jaworski

In 1930, two Fulbright lawyers were representing a client in Galveston seeking to have a $10,000 trial court judgment set aside. The Houston lawyer on the other side, Arthur Dyess, sent a young associate to argue to the court of appeals.

“Dyess must not think much about his lawsuit to send such a young and inexperienced lawyer,” the Fulbright partners told each other.

The young lawyer was Leonidas Jaworski – Leon to his friends. And he ate the Fulbright partners’ lunch that day in court.

Born in Waco and the son of an evangelical minister, Jaworski breezed through high school and college and finished law school before his 19th birthday. That same year, 1926, he became the youngest person to be licensed to practice law in the history of Texas.

Jaworski spent the first four years of his legal career in Waco, defending moonshiners during Prohibition. A client known as “the king of North Texas bootleggers” paid Jaworski $1,000 to clear him from charges of conspiracy to violate state liquor laws. He did.

In 1929, Jaworski represented Jordan Scott, a poor, uneducated black man accused of murdering a white couple.

The Waco Evening News and the Waco News-Tribune published articles citing local leaders of the Ku Klux Klan threatening to kill Jaworski for his vigorous defense of his client.

“As you might imagine, he fell out of favor with many in the Waco area because of that case,” says Repass.

While the jury found Scott guilty, lawyers and judges following the case praised Jaworski for his courage and legal skills in defending such an unpopular client.

In 1931, Fulbright partners convinced Jaworski to join their practice.

A decade later, Jaworski and more than a dozen other Fulbright lawyers left the firm to join the U.S. Army. Initially assigned to Fort Sam Houston where he prosecuted court-martial cases, Jaworski was appointed to investigate and prosecute a case in which German prisoners of war were accused to murdering one of their own. It was the first major case conducted on American soil under the Geneva Convention of 1929.

When Jaworski scored a conviction, the U.S. Defense Department assigned the Houston lawyer to lead the new war crimes branch of the Judge Advocate General’s office in Paris and then in Germany. By 1945, Jaworski had been promoted to colonel and was appointed to lead the investigation into atrocities committed at the Dachau concentration camp in southern Germany where Nazis murdered more than 41,000 Jews, Catholics and other political prisoners.

In January 1946, Jaworski returned to Houston and to Fulbright as a partner. It didn’t take him long to impress his colleagues and clients with his courtroom skills.

In the 1950s, legendary Houston oil wildcatter Glenn McCarthy hired Jaworski to defend him against assault and battery charges in California. The opposing lawyer said that McCarthy – like most Texans – was “arrogant, uncivilized and an ill-behaved braggart.”

In his closing argument to the jury, Jaworski said he was happy that brave Texans who fought alongside courageous Californians during World War II and who were buried side-by-side on the battles in Europe did not have “to listen to such derogatory remarks of a desperate lawyer.”

At that moment, a woman on the jury burst into tears. Her son had been killed in WWII and was buried next to a soldier from Texas. The jury deliberated for less than an hour before ruling for McCarthy.

“Jaworski really must be something if he can make a California juror cry for a Texas millionaire,” McCarthy is quoted as saying.

In 1960, U.S. Senator Lyndon B. Johnson hired his friend Jaworski to represent him in a lawsuit brought by Republican John Tower, who sought a court order to prohibit LBJ from campaigning for his senate seat while also running for vice president.

Two years later, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy hired Jaworski to be a special prosecutor in a case against Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett, who was preventing African American college student James Meredith from attending the University of Mississippi despite a federal judge’s order.

“The president and I have talked this over and we both have decided that you are the appropriate one to act as prosecutor,” Kennedy told Jaworski, according to firm documents. “We know it is a difficult and thankless task we’re asking of you. Will you take it?”

Jaworski did, but it came with a personal sacrifice. The Jaworski family received scores of threats, including some from friends who felt the lawyer had betrayed the South. Meredith was allowed to attend Ole Miss and Barnett left the governor’s mansion.

“Back in the early 1960s, this was not the smart business decision because we had a lot of clients that may have supported Gov. Barnett,” Repass says. “The firm stepped up and took on that representation. That’s something that we take a lot of pride in. That kind of leadership echoes for decades, and it continues to echo down the halls of the law firm.”

As this was going on, lawyers at Fulbright named Jaworski their managing partner. The firm flourished, growing to more than 100 lawyers and achieving record profits.

Then came Oct. 20, 1973. President Richard Nixon fired Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox, which meant that a replacement was needed.

“After the ‘Saturday Night Massacre,’ they need someone to come in as special prosecutor and handle the case properly. They looked and looked and Jaworski was it,” Repass says. “He was the package that they wanted.”

Jaworski initially said no, but then agreed after meeting with Robert Bork and Alexander Haig, who promised he would have complete independence.

“When Jaworski announced to the firm his plan to be the Watergate prosecutor, others at the firm said, ‘Leon, you are out of your ever-loving mind. This is a no-win deal.’ He was thought to be a whitewash candidate,” says Hall, who worked with Jaworski on several matters.

“But a year and a half later, he had been on the cover – favorably – of just about every periodical in this country – Time, Life, U.S. News, you name it. All of them said he did an incredible job,” Hall says. “He was the most prominent lawyer in the United States for a period. It put our firm more on the map than it had been nationally and internationally.”

Jaworski made the biggest news when he subpoenaed 64 audio recordings from the Oval Office and convinced the U.S. Supreme Court in July 1974 to order the White House to turn over the tapes. Two weeks later, Nixon resigned.

Jaworski returned as a partner to the law firm in September 1974, but he declined to take any new leadership roles. He died at age 77 in 1982.

Rapid Growth and Expansion

By the 1980s, Fulbright had grown to more than 280 lawyers, making it one of the largest law firms in the U.S. It opened offices in Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, San Antonio and London. In 1989, Fulbright acquired Reavis & McGrath, a 110-lawyer firm with offices in New York and Los Angeles.

Fulbright’s biggest deal came in 2013, when it combined with London-based Norton Rose, which has more than 2,000 lawyers outside the U.S. As part of the merger, Fulbright dropped the name Jaworski and was renamed Norton Rose Fulbright. Coincidentally, Norton Rose is also celebrating its 225th anniversary as a law practice in Europe.

The expansion continued in 2017, when Norton Rose Fulbright acquired New York-based Chadbourne & Parke, which significantly improved the firm’s corporate transactional practice on the East Coast.

The mergers, according to Pecht, were strategic and needed in order to continue to serve their clients and compete against other expanding corporate law firms.

“Our clients wanted to have a global firm. They had problems that were not just unique to the United States or North America. They had problems that were cross-border in nature,” he says. “We had offices in a lot of different places – London, Hong Kong, Middle East. But these were relatively small offices. Our clients wanted scale. They wanted heft. They wanted an ability to deal with their problems wherever they were.”

Pecht says that Fulbright leadership saw their competitors – particularly Houston-based Baker Botts and Vinson & Elkins – growing by hiring individual laterals or small groups to join specific offices.

“That is a slow, painful, difficult process. We decided there were better ways to do it … to combine with other firms that already had established footprints,” he says. “We could merge with them and they’ve already spent the money to build those offices. We don’t have to do those onesies and twosies in each of those locations. That was, to us, a better path to the success we wanted to achieve. The old times were great, but the world was changing. The practice of law has changed so dramatically.”

Hall, who joined Fulbright in 1957, agrees that much has changed about the practice of law during the past six decades, including technology, which allows lawyers to do their work from basically any location.

Lawyer compensation is also substantially higher. Fulbright paid new rookie lawyers between $5,000 and $10,000 per year in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, the firm pays newly minted attorneys just out of law school $190,000 a year. Records show that R.C. Fulbright was paid $25,000 to $40,000 a year during the 1920s and 1930s. Profits per equity partner at Norton Rose Fulbright in 2018 were $907,000, which is actually modest by the standards of most large corporate law firms.

“The legal practice has changed,” Hall says. “There have been so many people flooding into Houston and the other big firms that the law practice is more of a business. There’s not the personal relationships. It used to be that you did deals with the same people and litigated against the same people. As that eroded, people started turning sharper corners.

Hall says the relationships among the firms also has evolved.

“I remember when one of our lawyers had gone with another big firm. He called me and said he would like to change his mind,” Hall says. “I said, ‘Well quit your job and start interviewing.’ I immediately went to the managing partner of that big firm and said we didn’t call him, he called us. Now, the managing partner of the other firm is trying to hire our managing partner.”

“The culture changes [with expansion], Hall says. “I don’t even know everybody in Texas anymore. When I came here to run the employment [practice], I knew everybody, everybody’s wife and most of their children.”

That being said, Hall and others believe Jaworski would be proud of the firm today.

“I think the founders would be amazed how at the depth and expertise that we now have with these 4,000 lawyers in 29 countries and how we are able to serve our clients so much more than we ever have before,” Pecht says.