Editor’s note: This story was originally published on Dec. 16, 2019.

At the beginning of her law practice in the mid-1990s, Macey Reasoner could sense the vibes when she walked into a courtroom.

“Oh, you’re Harry Reasoner’s daughter,” was the comment she most often heard. She knew that some would dismiss her as a novice looking to trade on a family name that carried serious weight in the Houston legal community.

Her older brother Barrett Reasoner, who started as a Harris County prosecutor in 1990, was similarly aware of the long shadow his dad casts.

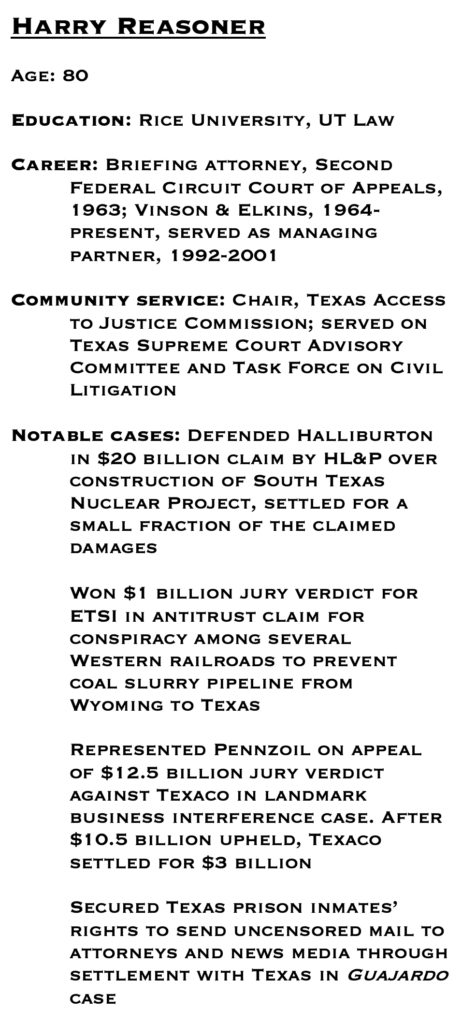

During his storied career, which continues at age 80, Harry Reasoner has been involved in some of the biggest trials and appeals in history. Clients pay as much as $1,500 an hour for his counsel. He led one of the state’s most prestigious corporate law firm, Vinson & Elkins, for nearly a decade. He set the bar for pro bono work, donating his services to marginalized clients such as Texas prison inmates.

It takes courage to follow a famous parent into the same profession. Once the Reasoner siblings chose that path, they were determined not to be defined by their father’s accomplishments.

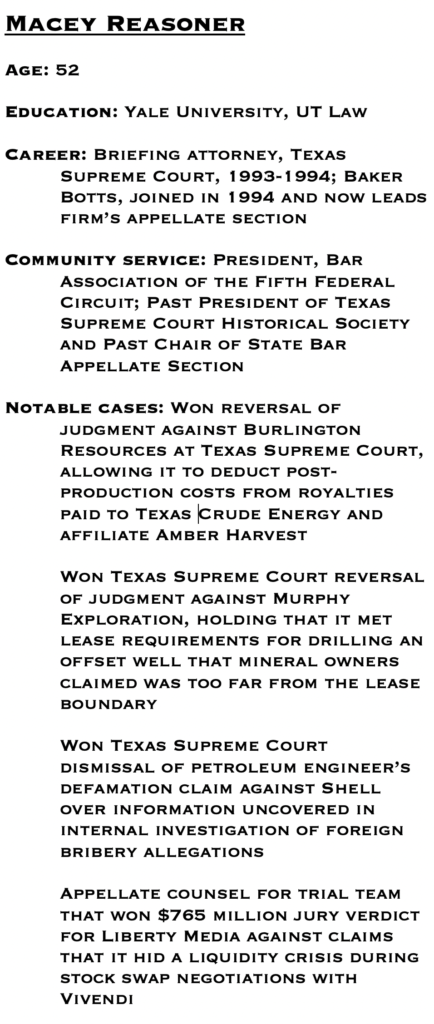

It wasn’t long before Macey, who assumed husband Bob Stokes’ surname, started winning appeals and building a reputation as a go-to lawyer for corporate clients looking for a skilled appellate advocate.

“I was always proud to be associated with him and appreciated when they brought it up, but I was glad as I got older I stood more on my own,” she says.

Macey, 52, heads the appellate section at V&E rival Baker Botts and has won a string of victories at the Texas Supreme Court for energy clients such as Shell, Burlington Resources and Murphy Exploration.

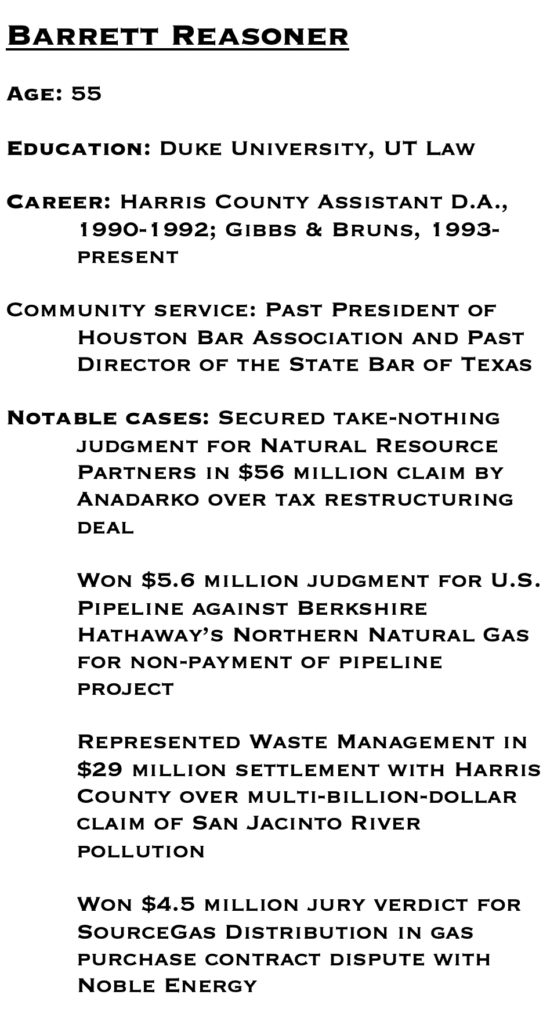

After two years as a prosecutor, Barrett, 55, began building an enviable litigation practice at Gibbs & Bruns. Last month he won a take-nothing judgment for Natural Resource Partners, which had been sued by Anadarko for $56 million over a tax restructuring deal.

“We both had the view that if we were going to do this, by God we were going to do it well and overcome anybody’s preconception we were just some famous lawyer’s kid,” says Barrett. “That has pushed us to work very hard at what we do.”

Harry and his wife, also named Macey, are unabashedly proud of their children. Neither pushed them toward a specific career, but both are grateful they decided to practice law in Houston.

“I hear constant praise about both of them,” says Harry. “I’m now at the stage of life where I have to be known as Barrett’s father and Macey’s father.”

Mom Macey notes that there are plenty of successful father and son lawyer duos, “but I think this triumvirate is fairly unusual.”

The Reasoner family of attorneys recently sat down with The Texas Lawbook to discuss their careers and relationships, including the first time Barrett and Macey appeared together in a courtroom this past July.

Humble beginnings

Harry grew up on a farm outside San Marcos, milking cows and raising pigs for 4-H competition. His parents, an auto mechanic and a school teacher, were focused on education and hard work, values that Harry used to become a state champion high school debater.

Caught up in the excitement of the space race, he entered Rice University tuition-free with dreams of becoming a physicist. He graduated with a degree in philosophy and decided to go to law school even though he wasn’t sure he wanted to be a lawyer.

It was in Austin where Harry met Macey, the gifted daughter of Gus Hodges, a popular civil procedure professor at the University of Texas School of Law. Fascinated by the logic problems posited by her father at the dinner table, Macey set her sights on studying law.

“It’s a pretty remarkable family. They have legal legend genes on both sides,” says Tom Phillips, a former Texas Supreme Court chief justice who hired Stokes as a briefing attorney in 1993 and now works with her at Baker Botts.

Harry was Hodges’ student assistant when he and Macey began dating in 1962. After finishing law school on a 27-month program, Harry won a Rotary Fellowship to study at the London School of Economics. It was an enriching experience for the young man from Central Texas and one that Barrett would pursue years later.

While Harry was overseas, Macey finished her first year at the law school. They married in 1963 and Harry began a clerkship in New Haven with Judge Charles Edward Clark of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Macey transferred to Yale Law School but life intervened when she became pregnant. Instead, she went to work as a clerk typist in the admissions office.

Macey later pursued graduate studies at Rice University and became interested in using job training to empower people in need of opportunities. She worked in that field for 25 years, both as a professional and policymaker. In addition, Macey has been active in human rights organizations and served on executive committees of the Houston Ballet and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Building a legacy

Starting at Vinson & Elkins in 1964 at a yearly salary of about $7,800, Harry was mentored by David Searls, a nationally known antitrust litigator. Searls taught Harry to speak up when he disagreed with the firm’s senior partners. It was a lesson Harry would later pass along as managing partner when meeting with new associates.

Often litigating cases out of town in those early years, Harry credits his wife with doing the heavy lifting when the children were young.

“Their father worked very long hours, and I would sometimes ferry them downtown to eat hot dog dinners with their father so they could remember he was there,” says Macey.

Daughter Macey now understands what a “smart, manipulative move” it was for her mom to have the 7-year-old daughter call to find out when daddy was coming home for dinner.

“We married young, right out of college, and had children very young,” says the elder Macey. “I suppose one thing about their childhood is that we sort of grew up together.

“We never talked down to them and they really responded to that. They were both very intellectually curious from a very early age.”

In the 1970s, Harry helped save Halliburton from potential bankruptcy when it was sued for $20 billion over delays in the construction of the South Texas nuclear plant. During a deposition, Harry got the chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to admit that the plant owners, which included Houston Lighting & Power, had required the construction of a far more expensive plant than Halliburton’s subsidiary Brown & Root had contracted to build.

The lawsuit settled for what Harry says was less than 2% of the damages claimed.

In the late 1980s, Harry was drawn into the landmark case Pennzoil v. Texaco. Houston tort king Joe Jamail had won a stunning $12.5 billion jury verdict in Pennzoil’s business interference claim against Texaco, and Harry was hired to defend the verdict against Texaco’s vigorous appeal. In 1987, the First Court of Appeals in Houston affirmed most of the judgment, leading to a $3 billion settlement.

In 1989, Harry won a record $1 billion antitrust award for ETSI Pipeline against Santa Fe Corp., part of a massive case against several Western railroads. The pipeline company accused the railroads of conspiring to block construction of a $3 billion coal-slurry pipeline.

The railroads settled for $585 million, of which V&E received one-third as a contingency fee. The firm used some of the fee to endow chairs at a number of law schools, and the rest was distributed to partners.

Harry assumed the prestigious position of firm managing partner in 1992. He put his progressive mark on Vinson & Elkins through programs to increase pro bono participation, launch women lawyers to partnerships, and offer insurance benefits to same-sex couples.

“He’s been the face of Vinson & Elkins for many, many years. He’s certainly considered the best trial lawyer the firm has ever had or seen,” says Patrick Mizell, a former Houston trial judge and now a partner at the firm.

Harry has earned the admiration of many for his pro bono work. In the 1990s, he defended the University of Texas School of Law against a challenge to its use of affirmative action in admissions. As chair of the Texas Equal Access to Justice Commission, he has helped raise tens of millions of dollars to provide civil legal services for Texans in need.

“Lending his name to pro bono and access to justice has been monumental in the state. That’s where I think his force has truly played out,” says Paula Hinton, a former V&E partner who is now at Winston & Strawn.

Barrett remembers being a youngster watching his father in action fighting for the rights of prison inmates to send uncensored mail to their lawyers and to journalists.

The civil rights case, which began in 1971, spanned three trials and appeals. After the state settled in 1979, Harry served as ombudsman for the class of prisoners until a federal appeals court ended the court’s oversight in 2004. He estimates he spent several thousand hours on the case.

“Eventually I learned he was doing that for free and providing that kind of service is what lawyers ought to do,” says Barrett.

It was a lesson Barrett took to heart. Several years ago, he represented an inmate who had gone blind after prison officials ignored his complaints about severe headaches and requests to see a doctor. The inmate received an undisclosed settlement with the state.

The lions speak

As they grew older, the Reasoner siblings were learning a lot from their father’s friends, successful trial lawyers like Jamail and Jim Kronzer. Listening to them talk about their courtroom triumphs was not only entertaining but helped demystify the practice of law.

“Nobody’s doing any magic. It’s all about hard work and enjoying what you are doing,” says Barrett.

They also learned that the law is full of blowhards who try to bully their opponents when they don’t have the facts on their side. An important lesson for the future, Macey says, was “don’t let the turkeys get you down.”

Her father and brother laugh at Macey’s use of the term “turkey.” It was a reference to the rocky first meeting between Harry and Jamail.

The two were arguing opposing sides of a case Jamail had won against General Motors. When Harry, who was representing GM, challenged Jamail’s characterization of the evidence, Jamail looked over and blurted out, “You turkey.”

Later that night Harry picked up his home phone to hear Jamail apologize for his outburst. It was the beginning of a life-changing friendship.

In the early 2000s, Harry would turn to Jamail when V&E’s existence was at risk after the implosion of major client Enron. Harry hired Jamail to ward off litigation in state court.

“During the first hearing down at the courthouse, there were all these lawyers there about the Enron case and Joe said, ‘I want to know if any of you are going to sue Vinson & Elkins. I want to know right now,’” Harry recalls.

“Joe told them we had no exposure, that pigs would fly over the courthouse before anybody got a judgment against V&E. He was a big help to us.”

When Jamail refused to bill the firm, Harry had statues made of his friend for the law school, UT football stadium and Texas Heart Institute.

Shared qualities

Both Barrett and Macey went to Lamar High School and were named outstanding seniors. They were steered into summer jobs interacting with the public because Harry felt his stint as a waiter had taught him the importance of being nice to diners even when they were being rude.

Like his father, Barrett became a champion high school debater and started to think the law might be a good fit after all. He graduated from Duke University with a degree in political science, received a graduate diploma from London School of Economics and earned his law degree from UT in 1990.

Seeking courtroom experience, he signed with Harris County District Attorney Johnny Holmes for two years. It was a good move, especially when Barrett met Susan, a fellow prosecutor who became his wife. The couple have five children.

At Gibbs & Bruns, Barrett focuses his litigation practice on securities, oil and gas, construction, environmental and intellectual property matters. His clients include Kinder Morgan, Uber Technologies, Texas Children’s Hospital and Waste Management.

Firm founder Robin Gibbs, who had been mentored early in his career by Harry at V&E, was ready to hire Barrett fresh out of law school but respected his decision to start at the DA’s office. As soon as Barrett was ready to switch to civil litigation, Gibbs brought him into what was then Gibbs & Ratliff.

“It was evident right up front that he shared many of the qualities of his dad and his mother, and that made for a young lawyer who was obviously bright, with a terrific amount of initiative and skill for such a young lawyer, and equally a delight to work with,” says Gibbs.

In 2014, Barrett was part of a team defending Waste Management and co-defendant companies in a high-profile $3 billion pollution case brought by Harris County. The county said the companies were responsible for decades-old paper mill waste pits that contaminated the San Jacinto River.

The defense team methodically made the case that the companies had complied with disposal regulations that were in place in the 1960s or weren’t responsible for the site until much later. Hinton, his co-counsel, showed the jury a photo of herself as a gawky teen from that era to illustrate just how much time had passed.

The defense persuaded the judge to dismiss two-thirds of the county’s claimed fines mid-trial. On the morning of closing arguments to the jury, the county settled with the companies for $29 million.

Barrett is known as a zealous advocate who, like his father, is unfailingly polite and resistant to courtroom gamesmanship. He was inducted as a fellow of the prestigious American College of Trial Lawyers last year, an honor he shares with his dad.

May it please the court

Macey also excelled academically. She studied history at Yale University, where she met her future husband. Then it was straight to law school at UT, which she chose over Stanford, Chicago and Harvard because she wanted to practice in Texas.

Upon completion of her 1L year, however, Macey needed a break from the nonstop years of academic strain. Having been influenced by her mother’s love of art, she followed a path her mother had once trod and worked as an intern for a year at the National Gallery of Art and the National Portrait Gallery. At the National Gallery of Art, she helped catalogue the Vogel collection of minimalist and conceptualist art donated by a retired postal worker and a retired librarian who had bought works from up-and-coming artists.

After finishing her law degree, Macey won a plum position as a clerk for Justice Thomas Phillips at the Texas Supreme Court. The experience sparked her interest in appellate law, which she says suits her personality better than some of the “Rambo-esque stuff you might get at the trial level.”

“She was an astute analyst of the law and a critical thinker and a very clear writer,” says Phillips. “Being an appellate lawyer is a different art from being a jury lawyer.”

Looking to her father’s experience handling appeals, Macey writes and rewrites her briefs. During oral arguments, she is known as a focused, plain-spoken advocate who helps justices understand complex facts and legal concepts.

Although Macey has seen the ranks of female appellate specialists grow, it is still unusual to see two women going toe-to-toe. That happened in the first case heard by the Texas Supreme Court this term. The courtroom was filled with spectators watching her argue for ConocoPhillips against Austin lawyer Lisa Bowlin Hobbs in a dispute among heirs over royalty interest payments.

Earlier this year, Macey persuaded the justices to walk back its controversial Hyder decision on the hotly contested issue of who pays postproduction costs. The court said her client Burlington Resources could deduct those costs from royalties it paid to Texas Crude Energy and Amber Harvest.

In 2018, she won reversal of a judgment against Murphy Exploration for drilling an offset well that mineral owners claimed was too far from the lease boundary. The case was notable for the Supreme Court’s distinction of the technology and drainage for a horizontal well compared to a vertical well.

Another victory came in 2015, when the Supreme Court ruled that a Houston petroleum engineer could not sue Shell Oil for defamation after supposedly slanderous allegations in the company’s response to a Department of Justice investigation. The case reaffirmed that businesses could continue to internally investigate foreign bribery allegations involving their employees without being subject to defamation suits.

As chair of the state bar’s appellate section, Macey helped craft a program to allow litigants to apply for a lawyer to handle their appeal. She is currently supervising an associate at her firm who is handling one of those appeals.

Teaming up for port case

Recently Barrett hired his sister to help with an appeal for the Port of Corpus Christi, which has been locked in a contentious battle with a former commissioner over a proposed $2 billion oil export terminal project. The former commissioner, who operates a competing private entity, lost that appeal but raised other claims.

In July, the siblings stood together in a Nueces County district court arguing for dismissal of the private entity’s claims that the port authority had violated public contracting and bidding laws. The duo won after tag-teaming arguments centered on governmental immunity.

Barrett had appeared in that court before and enjoyed a rapport with the judge.

“He clearly listens to me and trusts me, but I could tell when Macey got up and started talking about the law that he thought, ‘I’m really getting the law here.’”

“I was a little nervous, working with family: ‘How is that going to go?” says Macey. “I loved it and wish it hadn’t taken so long to happen.”

After the hearing, the judge asked Macey if she saw any resemblance between Barrett and U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

“Well, I guess I’ve heard that before. I see it a little bit,” Macey replied before dropping the bombshell. “You know that’s my brother.”

Barrett responds good naturedly when his sister recounts the story, replying: “I always thought I looked like George Clooney.”

Generation rising

Harry still shows up at his office and relishes the legal game. He recently agreed to help Dallas personal injury guru Frank Branson defend a $242 million jury verdict against Toyota. Editor’s note: Reasoner was part of a V&E appellate team that successfully defended the $213 million judgment against Toyota, which was affirmed by the Fifth Court of Appeals in June 2021. Six months later, Toyota reached a settlement with the Reavis family, whose young children suffered permanent injuries related to seatback failure issues in the family’s Lexus.

With Barrett’s oldest in his second year of law school at UT and his youngest considering the profession, there’s a good chance the Reasoner name will continue to resonate in the Texas legal community for many years to come.

As for those early doubters curious about how Macey and Barrett would measure up as legal royalty, well they have long since gone silent.

“People see them as not only having the courage to do it, but to have succeeded independently in carving out their own reputation and place in the law firms and communities that they serve,” says Gibbs. “It’s all the more dynastic when you see something like this happen and it works for the children.”