In a typical year, legal writing guru Bryan Garner is away from his Dallas home almost half the time, crisscrossing the country on an admirable but difficult mission: teaching lawyers and judges how to write intelligibly.

Because of the coronavirus Garner, the founder and president of LawProse Inc., isn’t flying anywhere these days. As of May 18, Garner said he had not left his house in 69 days. But in a recent interview with The Texas Lawbook, he said “we are thriving” nonetheless.

For one thing, Garner had already jumped on the Zoom and Cisco WebEx bandwagon, supplementing some of his in-person seminars with videoconferencing for a law firm’s out-of-town offices, for example. In addition, Garner presciently decided two years ago that he and the four lawyers in his company could do without a downtown office. They’ve been working from home ever since.

“We’re never going to go back to pre-2020 normal, and I’m never going to be spending 180 nights on the road again, and that’s OK,” the 61-year-old Garner said. “I wouldn’t call it a semi-retirement at all, but I’m certainly enjoying being able to spend so much time in Dallas. And at the same time, law firms are highly motivated to get back to business and to figure out how they need to adjust and do more online, and that includes distance learning.”

Law firms have been drawn to Garner for help with legal writing since he started his company in 1991. He has conducted seminars for more than 200,000 lawyers and judges in venues including the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC.

“When I get interested in something, it tends to become a kind of monomania.”

He is easily the best-known legal writing expert in the nation and author of roughly 30 books. Among them are the updated Black’s Law Dictionary —Garner is editor-in-chief — and Garner’s Modern English Usage, which goes beyond legal writing. He co-authored two books with his friend, fellow syntax nerd and occasional sparring partner, the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

In 2018, Garner wrote Nino and Me, an intimate memoir of his friendship with Scalia. Garner also writes regularly about words for the ABA Journal.

“Bryan has done more than anyone to preach the gospel that lawyers and judges should use normal, accessible prose as much as humanly possible,” said Judge James Ho of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, a friend of Garner. “Deep in Bryan’s soul is a love of the law and a profound commitment to the principle that every citizen deserves to know and understand what the law is.”

During the current period of zero travel, Garner has turned to Twitter to stay busy, producing a series of videos titled “CURIOUS MIND” from his iPhone. He says he was inspired by videos posted by comic Ricky Gervais.

“It keeps me in practice,” he said. “I’m looking for something useful to occupy my time.”

Each episode begins with some music, followed by Garner’s musings on subjects ranging from irregular verbs to Shakespeare’s birthday and the Supreme Court.

One episode that focused on the pros and cons of footnoted citations drew more than 4,000 views, Garner said. He believes that lengthy citations in the text of briefs should be relegated to where footnotes go, in the interest of making the text itself more readable.

“Real writers wouldn’t dream of having extraneous words pervading their text,” Garner said.

But Garner acknowledged that “emotions run high on the subject” and noted that Scalia and Richard Posner were among those who thought citations should reside in the text. Garner ends each video with this recommendation: “Fall in love with language. It will always love you back.”

Garner has loved language since he was a teenager, but when he decided to make language his career, it wasn’t always a lovefest.

“He’s established himself as the leading authority in the United States on English usage and grammar, in the law and outside it, and he also did it the hard way, without institutional help,” said Ward Farnsworth, dean of the University of Texas at Austin School of Law and a friend of Garner. “He entered the arena of English-language commentary without an invitation but with massive talent and passion.”

Garner teaches at both the University of Texas and Southern Methodist University.

Born in Lubbock, Garner moved with his family to the panhandle town of Canyon when his father got a university position at West Texas State University. Garner said his father and grandfather had a keen interest in language and grammar.

‘A Kind of Monomania’

When he was 15, a girl told Garner he had a very good vocabulary. That launched him on a project copying 30 to 60 words a day from the Webster’s Second New International Dictionary into large notebooks.

“When I get interested in something, it tends to become a kind of monomania,” Garner said.

Because his grandfather Meade Griffin was a judge on the Texas Supreme Court (from 1949 to 1968), Garner became interested in the law. Shortly before he died, Griffin offered his law library to Garner, but he declined, still thinking he would become a professional golfer. At varying times in his childhood, Garner also wanted to become a paleontologist or herpetologist. Eventually, Garner went to the University of Texas for both his undergraduate and law school degrees.

In his first year at law school, Garner embarked on a private project to create a dictionary of legal usage, writing legal and linguistic notes and quotations on index cards and eventually filling two large card catalogues. When he graduated in 1984, Garner clerked for Judge Thomas Reavley of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

On the side, Garner decided to compile his notes into a book, though law professors had discouraged him from pursuing it. Publishers weren’t too keen about it either.

“I wrote to 33 publishers, and over six months I got 31 rejections,” Garner recalled. But Oxford University Press said yes, and his writing career began.

By the time the book came out, Garner had gone on to private practice at Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal in Dallas. His colleagues there had mixed feelings about the book after it was reviewed in The New York Times, Garner recalled.

“The senior partners were very warm and congratulatory,” he said. “The junior partners, however, were vaguely insulting and unhappy at the book.”

One senior associate went to the management committee and argued that Garner’s book royalties should go to the firm. After that, Garner said, “I pretty well realized, ‘I need to find a way out. I can’t stay here.’”

No Cake Walk

Garner landed at the University of Texas where he launched another project, The Oxford Law Dictionary, for Oxford University Press. But he had to raise funds to make it work, and after two years the project was scrapped, a devastating blow for Garner.

“A lot people will look at a career like mine and think it was just a cake walk the whole way, and of course it wasn’t,” he said.

His next step was the creation of LawProse in 1991.

“After this bitter experience, I didn’t want one dean holding the entire key to my future in his or her hands,” he decided. By launching his own company, Garner said, “I will teach, but I’ll teach practicing lawyers — not just students at one law school.”

After a slow first six months, LawProse took off, and Garner was booking legal writing seminars nationwide and later, worldwide. “I’ve never looked back,” he said. But his urge to write persisted, and he worked on what he wanted to call “Garner’s Law Dictionary,” with the goal of besting the venerable Black’s Law Dictionary, which he thought “was not particularly good.”

Word spread about his project, and in 1994, out of the blue, West Publishing invited him to become editor-in-chief of Black’s. “They gave me carte blanche to do what I wanted to, to remake Black’s Law Dictionary along more scholarly lines,” Garner said.

So, Garner tore it up and made the dictionary his own. “If you were to put the 11th edition of Black’s alongside the 6th, you would not even think that it was a derivative work,” Garner said.

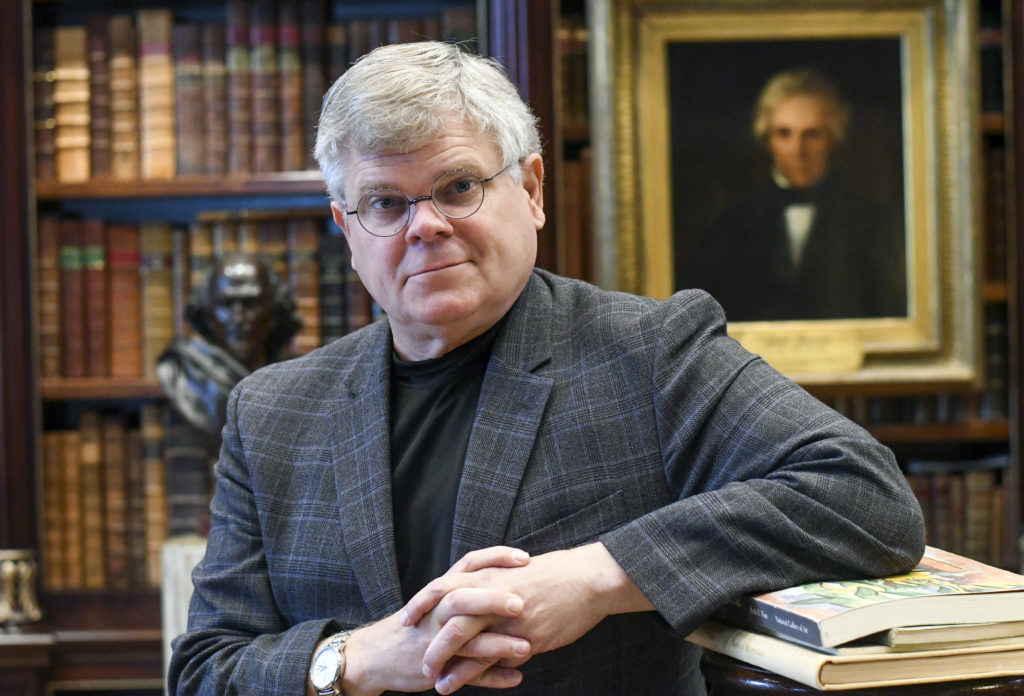

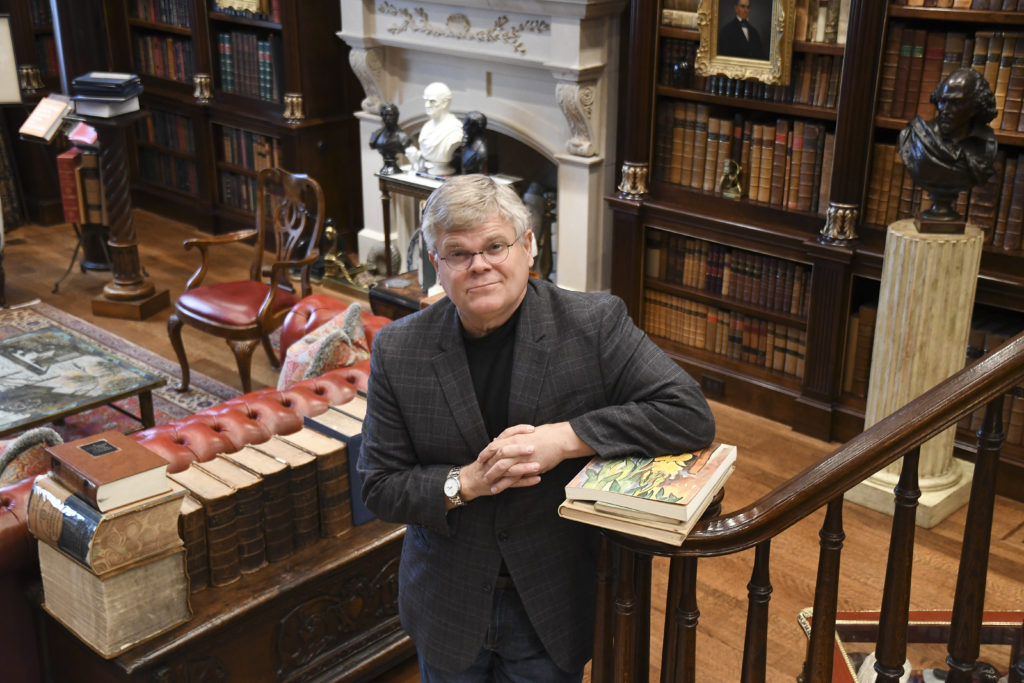

Meantime, Garner amassed a huge collection of books on the law and language. Garner estimates he and his wife Karolyne Cheng – also general counsel of LawProse – have 37,000 books at their Dallas home. The Twitter videos filmed in his home office show only a small portion his collection in the background, he says.

“This is a room that I had specially made for sets of books,” he said. “Each bookshelf is two feet deep, meaning that for every book spine you see, that represents two and a half books. That way, you can double-shelve the books and you know what’s behind.”

Among other sets, he has every Harvard Law Review from the first volume in 1887 to now.

In another wing of the house called the scriptorium, Garner has 5,000 square feet of book space. “That’s where I keep my dictionary files. We own between 4,000 and 5,000 dictionaries, and more than 1,200 grammars.”

The collection came in handy when Garner was asked in a post-9/11 business interruption insurance lawsuit to research the meaning of the word “vicinity” – a key word in determining whether a company was close enough to the Twin Towers and the Pentagon to be compensated.

“I think I quoted from more than 700 dictionaries,” he said.

On top of everything else, Garner in 2004 began videotaping interviews with American judges, lawyers and even some journalists (including this reporter) about their writing for use in his seminars and to develop “a body of work that would inspire law students to write better.”

Scalia and Garner

After taping more than 150 interviews, in 2006 Garner decided to climb the mountain and ask current Supreme Court justices to do the same. He started off with Scalia, whom he had met before. Scalia balked at first, but then acquiesced. Once Scalia said yes, inviting the other justices became easier – except for the reclusive David Souter.

“I’ve never been satisfied with my own prose,” Souter said in a letter to Garner. “Since I don’t think my own work is worth writing home about, I’d feel presumptuous telling other people what to do.”

The transcribed interviews with the other justices were published in the Scribes Journal of Legal Writing and stand as probably the deepest and most important study of how justices craft their own writings and consume the writing of others. Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. famously told Garner, “I have yet to put down a brief and say, ‘I wish that had been longer.’’’

Garner’s approach to Scalia for the interview fostered a close but sometimes stormy friendship between the two, chronicled in detail in Garner’s Nino and Me. Garner and his wife were among the last people to see Scalia alive in 2016. They joined the justice on a trip to Singapore and Hong Kong just days before Scalia died at a Texas hunting ranch.

In conversations with Scalia in 2006, Garner suggested that they co-author a book titled Making Your Case: The Art of Persuading Judges. Scalia agreed. But as the writing went back and forth, the project almost imploded. He had sent some pages of manuscript to Scalia’s chambers, and a few days later Garner called Scalia to see how things were going.

“I’m not going to be able to do this book. I’m sorry,” Scalia said. “You’re not using my stuff. Frankly, I think you just wanted my name on your book.”

Garner was shocked, and he tried to change Scalia’s mind with some revisions, but the justice was adamant. It then dawned on Garner that Scalia had been looking at a workbook he had sent to the justice, rather than the manuscript pages. Once Scalia read the correct pages, he was back on board.

“Bryan, this is wonderful,” Scalia exclaimed over the phone. “This is not what I’ve been looking at. This is first-rate work.”

Garner was close enough to Scalia that he sometimes gave the justice advice on ways to smooth his rough edges. One such effort recounted in Nino and Me involved this reporter.

In 2008, Garner and Scalia promoted their book Making Your Case by team-teaching the book at the Kennedy Center. I covered the event, and Garner invited me to come backstage to talk with Scalia. When Garner broached the subject, Scalia said, “I don’t want to talk to Mauro!” Over the years, I had written stories that Scalia did not like – he once called one of my articles “mauronic” – which likely explained his refusal to talk to me.

But according to the book, Garner urged Scalia to change his mind, telling him that the way to have a good relationship with a journalist is to show interest in the journalist and “be your charming self.” Scalia acquiesced and met with me. Sure enough, he charmed me by asking me about my Italian American family. Any hard feelings melted away, at least for a while.