UPDATE: Four Sonic Drive-In officials apologized Thursday evening directly to the seven African American families whose teenagers were told by a Sonic employee that they needed to leave the fast food restaurant’s parking lot or the police would be called, according to people who attended the meeting.

Kimberly-Clark Deputy General Counsel Shonn Brown, who attended the meeting with her 16-year-old son, said the families and Sonic officials talked about what happened and suggested measures Sonic could take “specific to African Americans and their experience as customers.” Brown called the meeting “healing and productive.”

The parents organized a community rally at the Sonic on Sunday afternoon, where hundreds of cars drove through to show their support for the teenagers.

In a statement issued to The Texas Lawbook over the weekend, Sonic apologized to the seven teens and said it is revising certain policies and bolstering its training program to include unconscious bias with a focus on the African American experience.

The full statement:

“Sonic unequivocally opposes racism and intolerance of any kind. We celebrate diversity and strive to consistently create an environment that highly values inclusion.

Unfortunately, a recent event at our Drive-In restaurant in Dallas, Texas, was handled inappropriately and did not live up to our standards. As soon as we were alerted to the situation by the families involved, we engaged in a valuable discussion on race, equality and a deeper understanding of social justice issues and ways we can improve as a company.

Sonic deeply and sincerely apologizes to the teenagers involved in the incident. We simply must do better going forward. To that end, we are revising our policy to ensure the appropriate level of manager is involved in handling matters with our guests. We are also bolstering our training program to include consistent unconscious bias training, with a focus on the African American experience, as we foster a more inclusive environment for our team members and guests.

We thank the families involved for their productive and positive discussion and look forward to our continued conversations.”

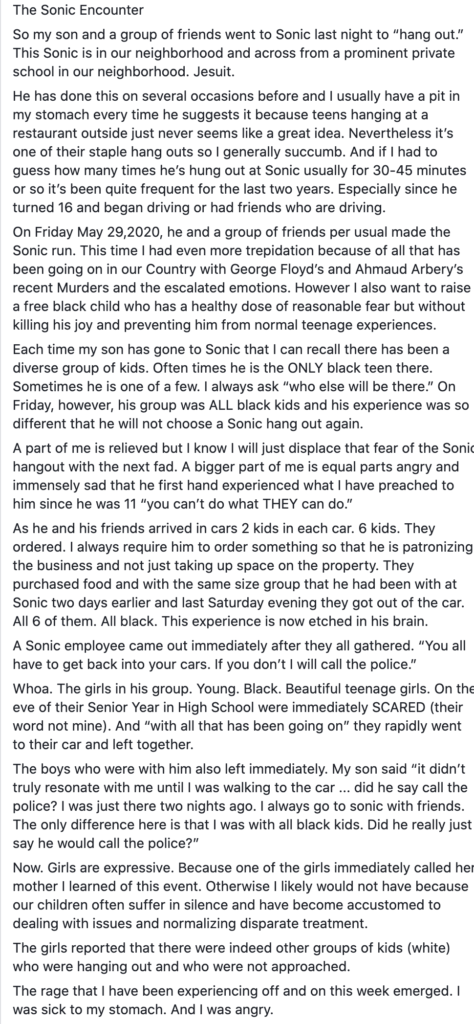

Shonn Brown was furious. It was just before midnight last Friday. She was parked at a Sonic restaurant in North Dallas across from Jesuit College Prep.

Only a half hour earlier, her 17-year-old son and a half dozen of his friends had been in that exact spot, about to order food and slushes to celebrate the end of school as new rising seniors. Suddenly, a Sonic employee approached.

“You all have to get back in your cars,” the Sonic employee said. “If you don’t, I’ll call the police.”

Evan Brown, Elle Grinnell, Zoë Purdy and the others — all African Americans — were stunned at the threat to call the police. This was their regular hangout. They always ordered food and just talked. Never any mischief. No complaints from Sonic ever. There were groups of white kids in the Sonic parking lot, too, but they were not asked to leave and no one threatened them with calling the police.

Abandoning their cravings for root beer floats and tater tots, Evan, Elle, Zoë and the others left right away. Some called their parents. Some arrived home shaking. Some initially suffered in silence. Shonn Brown was stunned. Needing to see for herself, she drove immediately to the Sonic. She saw it firsthand: Groups of white teens loitering in the Sonic parking lot and no one was ordering them to leave or threatening to call the cops.

“My anger was at a boiling point,” Brown said.

The parents of the teenagers say this specific incident needs to be spotlighted to show that racism continues to be a real and terrifying factor in the lives of people of color every single day. And they say that they want to use what happened last week as a teachable moment and to affect a meaningful or substantive change.

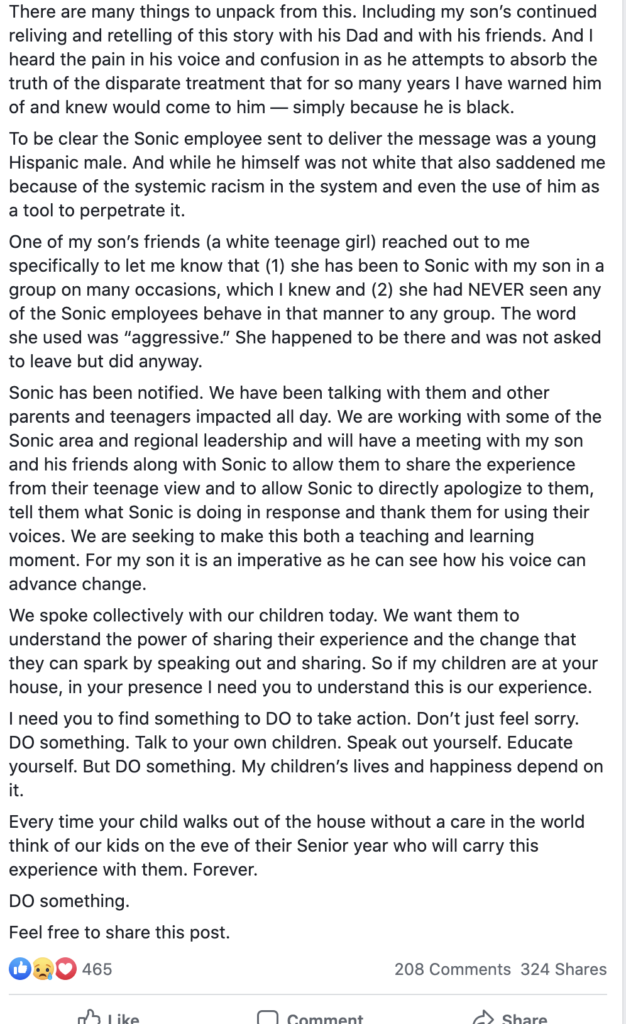

The first step in effectuating change took place Sunday, when Brown posted on Facebook a 1,621-word account of what happened in detail.

“STOP and read this story,” Brown wrote. “This is my life. This is my Black Son’s life. This is our reality. Will you ACT” Or read and click the sad face and keep moving like business as usual. DO something. Act.”

In the three days since, Brown’s post has been “shared” 369 times. The original post and the shared posts have received hundreds and hundreds of comments and responses.

In an email Wednesday afternoon, a spokesperson for Sonic’s parent company, Inspire Brands, said it would be “premature” to participate in an interview with The Lawbook or issue a statement since conversations with the families are ongoing. The company offered to follow up at the end of the week.

The problem for Sonic isn’t just that they are facing allegations of racial stereotyping and discriminatory activity. It’s also that they picked the wrong teenagers and the wrong families.

- Evan’s mother, Shonn, is the deputy general counsel of Kimberly-Clark Corporation. Evan’s father, Clarence Brown, is the general counsel of Kronos Worldwide.

- Elle’s mother, Tasha Grinnell, is a vice president and assistant general counsel at Neiman Marcus Group and her father, Nevin Grinnell, is the chief marketing officer of a regional transportation operation

- Zoë’s mother is Dallas County Associate Judge Monica Purdy and her father, Toby Purdy, is a marketing executive at a Dallas area events services company.

- Parents of the other kids involved include a surgeon, a dentist, a business owner, immigration lawyer Irene Mugambi and an HR executive at an engineering firm.

Multiple lawyers, including Dallas trial lawyer Michael Hurst and Sharyland general counsel-turned-chief executive Stacey Doré, wrote letters directly to Inspire Brands General Counsel Nils Okeson.

“[I] invite you to immediately take action and use your position and platform for righteousness and to help be a solution to escalating racial tension and discrimination against not only my friends’ children but against a demographic where I suspect Sonic derives substantial revenue,” Hurst says in his letter.

“I am an avid Sonic customer, and this is our neighborhood Sonic,” Doré wrote in her letter. “It sickens me that these young people were treated this way.”

But Judge Purdy said that their career positions shouldn’t be the point. She said she purposely left out her job title when she began the dialogue with Sonic.

“I am speaking as a mom, as a parent,” she told The Texas Lawbook.“I’m not speaking as a judge here in Dallas. “I would want them to respond to me if I were a blue collar worker that punched a clock. I think it should be no different. A parent is a parent is a parent.”

Just as the job title of a racially targeted teen’s parent should not matter, Tasha Grinnell said she hopes the story of her daughter and friends teaches people that racial profiling has no Zip code.

“Police are not only being called to locations that are saturated by crime, but it’s also happening in what people would consider to be a safe, multicultural and multiracial neighborhood,” Grinnell told The Texas Lawbook.

“I want people to know this is happening with our children in our neighborhood,” said Grinnell, a former senior in-house counsel at McAfee who joined Neiman Marcus in March to oversee the retailer’s litigation department and labor and employment issues. “It’s happening where people are educated and exposed … and in a place where our children have felt safe since they were babies, but unfortunately now that they’re driving and we’re not with them every minute, we can’t shelter them alone.”

“It’s going to take the entire village to keep our children safe,” she said. “I need my white neighbors, white colleagues and my children’s white classmates to know that if you see something and you see injustice, you’ve got to step up and you’ve got to make a difference and a change in order to protect your friends.”

‘Simply Because He is Black’

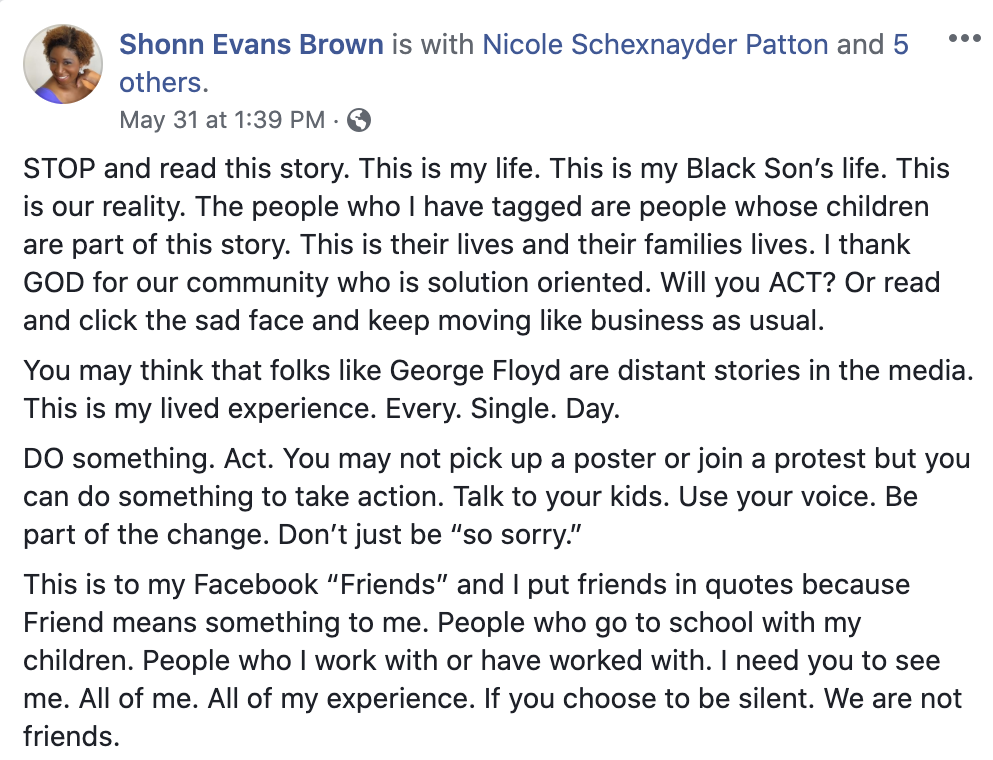

The night of the incident at Sonic, May 29, Shonn Brown was unable to sleep. The next day, she listened as Evan told and retold the story over and over as a method of dealing with the incident internally.

“I heard the pain in his voice and confusion as he attempts to absorb the truth of the disparate treatment that for so many years I have warned him of and knew it could come to him [one day] – simply because he is black,” she said.

Brown knew she needed to do something. Her thoughts immediately went to her friend, Julia Simon, who is the chief legal officer of Mary Kay.

In early May, Simon published a Facebook post revealing that her son had been jogging in the Preston Hollow neighborhood where she and the Browns live, when a white woman yelled out to him: “Stay out of this neighborhood.” The incident occurred just as the nation was learning of the murder of Ahmaud Arbery, who was jogging through a Georgia neighborhood when he was attacked and fatally shot by two white men on Feb. 23.

“I’m sharing this along with a story of what happened to my black son in a neighborhood he has lived in his entire life just a week ago,” Simon wrote on Facebook on May 7, detailing what happened to her son.

“While there was no gun involved in this situation (thank God), the danger that comes with the assumption that my son doesn’t belong is a problem that keeps me constantly worried about his safety,” Simon wrote. “Constantly. My friends of all races, I need your help dispelling the notion that my son is dangerous because he is black. If anything, it is unfortunately the case that he is IN danger because he is black. I don’t need prayers right now. I need action designed to stop this insanity.”

On Sunday, May 31, Shonn Brown opened the Facebook app on her iPhone.

Until recent weeks, Brown’s Facebook posts predominantly documented life’s lighter moments. She featured the positive aspects of her life at home while social distancing: virtual get-togethers with friends, supporting local businesses with take-out, participating in at-home workout challenges — even mastering the viral TikTok dance challenge to the popular Hip-Hop song du jour “Savage” with her daughters.

But current events have compelled Brown to use Facebook to acknowledge the all-too-familiar narrative of black men in America being killed at the hands of white police or being racially profiled just from the color of their skin.

This Facebook post wasn’t sharing someone else’s confrontation with racism or linking to a newspaper article about a racism-related incident.

This was the personal story of her son and her family. The words she typed demonstrated the fear she has for her son.

“Part of me is equal parts angry and immensely sad that he firsthand experienced what I have preached to him since he was 11: ‘You can’t do what THEY do,’” she wrote.

Then, Brown told the story of last Friday night in detail.

Tasha Grinnell was with Shonn Brown at a mutual friend’s outdoor gathering when Elle called describing what happened at the Sonic just a mile down the road. Grinnell told Brown, who called her son.

“Who told you?” Evan asked.

“Part of mental processing for a lot of these kids, particularly African American boys, is that they don’t want to call attention to themselves,” Brown told The Texas Lawbook. “They act like it’s normal. This is not normal … it’s not how it is now and how it needs to be.”

Evan told his mother that he and his friends arrived at the Sonic about 10:45 p.m. They were ordering sodas and hamburgers and standing around their cars, trying to keep a social distance, when a Sonic employee approached and gave the teenagers the command to “get back in your cars. If you don’t I’ll call the police.”

“To be clear, the Sonic employee sent to deliver the message was a young Hispanic male,” Brown said. “And while he himself was not white, that also saddened me because of the systemic racism in the system and even the use of him as a tool to perpetrate it.”

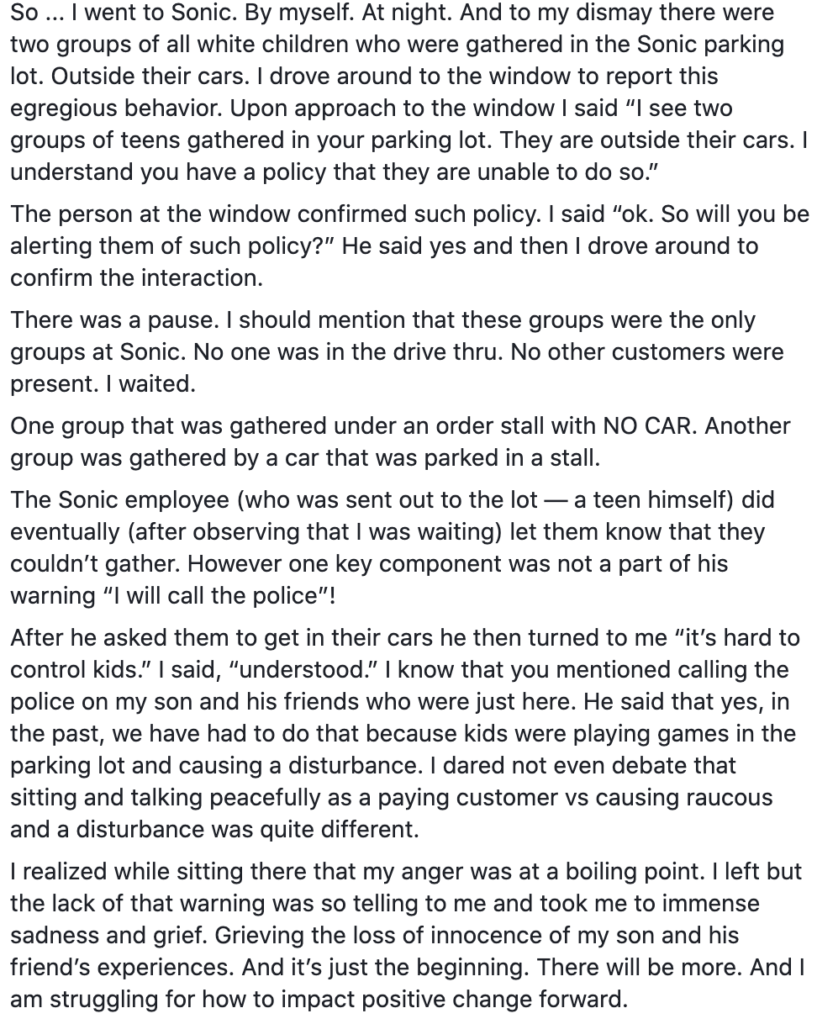

Upset, Brown drove to Sonic by herself. There, other groups of teens — white teens — were still hanging out.

Brown drove to the Sonic window to “report this egregious behavior.” She asked about Sonic’s policy regarding people gathering in the parking lot.

The Sonic employee confirmed the policy and said he would tell the teens to leave. The Sonic employee, noticing several minutes later that Brown had not left, told the kids they needed to go.

“One key component was not a part of his warning [to the white teens],” she said. “I will call the police.”

Over the weekend, Brown realized she didn’t want the message to be simply be to “stay away” from that Sonic “forever.” She wanted it to have greater meaning, a teachable moment.

She heard from Winston & Strawn lawyer Geoff Harper’s daughter, who was there the night before with one one of the other groups. She confirmed that the Sonic worker’s threats of calling police were directed only at Evan’s group. Upset, she had left shortly after and told her parents about what happened.

After Brown told the story to close friends, they helped her find the appropriate contact for Sonic. Brown and Purdy got in touch with two regional managers, both mothers themselves, and they told them their children’s story.

Purdy said the Sonic officials apologized and expressed that the events shouldn’t have happened.

“While I appreciate that, it did not happen to me,” Purdy said. “The apology is owed to the children.”

Sonic, Purdy and Brown arranged a meeting Thursday at the restaurant with the full group of parents and their children, where Sonic representatives will be given the opportunity to hear from the teens directly, apologize and openly discuss how they can be better going forward.

The parents created an online petition Wednesday to demonstrate to their children — and Sonic — that their community stands with them. Although they had originally aimed to collect just 500 signatures, they increased their goal to 5,000 as the signature total entered four digits on the eve of their meeting.

“My hope is that [Sonic] will implement change throughout their organization,” Grinnell said. “What I would say if I were advising them is I would like for us to take a look at the policies and procedures and ensure they’ve implemented anti-discrimination policies companywide. I would ask that they would have a no tolerance outlook so that if and when their employees do not follow the anti-discrimination policies, those employees will receive discipline up to including termination.

If Sonic leaderships commits to any suggestions for addressing racial issues provided by the families at Thursday’s meeting, it could present an opportunity for more widespread corporate reform beyond the popular drive-in chain. Sonic’s parent, Inspire Brands, has a portfolio of more than 11,1100 restaurants, 1,400 franchisees and 325,000 employees in 16 countries. In addition to Sonic, Inspire Brands’ restaurants include Arby’s, Buffalo Wild Wings, Rusty Taco and Jimmy John’s.

“They have the ability to truly use this and make a difference,” Grinnell said.

As much pain as last weekend’s events have caused, the parents are pleased that it has led to a teaching moment. But they shudder over the possibility that it could have turned out much worse.

“Thank God this was not a tragic situation,” Brown said. “It was an educational situation that raised awareness, but thank God nothing really happened.”