© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Natalie Posgate

Staff Writer for The Texas Lawbook

College was a distant dream for Michelle Erbeyi, a 2004 Hillcrest High School senior who excelled in history and showed proficiency for law and international issues.

The Hispanic teen – the first in her family to even make it through high school – was the oldest of seven children. Her dad was a chef. Her mom worked at Albertson’s. Their combined income was less than $40,000.

“That doesn’t leave much for college,” said Erbeyi.

Halfway through her senior year, Erbeyi learned about a college scholarship for low-income minority high school students from an unlikely source: lawyers.

Erbeyi is one of more than 500 Texas high school students – a large majority of whom are Hispanic, African-American and Asian – to have part or all of their college education paid by individual lawyers, law firms and legal organizations in the state during the past decade.

Since 2001, Texas lawyers and firms have quietly awarded more than $1.6 million in financial aid to low-income students or students of color who have an interest in law, government, history, business or even the arts and who otherwise wouldn’t have had the financial means to get a higher education.

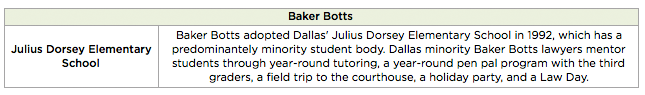

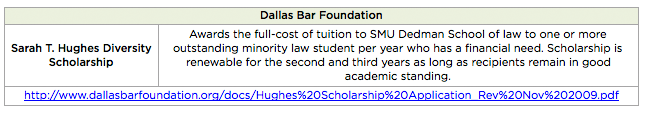

“As a profession, we’ve been working hard to open the doors to historically underrepresented minorities,” said Tim Mountz, a partner in the Dallas office of Baker Botts, which is one of more than a dozen law firms that funds the Dallas Bar Foundation’s Sarah T. Hughes Diversity Scholarship, which has paid all tuition costs for 26 low-income minority students to attend SMU Dedman School of Law during the past 10 years.

“The increased costs make it seem more daunting to someone who doesn’t think they have the resources,” said Mountz, who also is the vice chair of the board of trustees at the Dallas Bar Foundation.

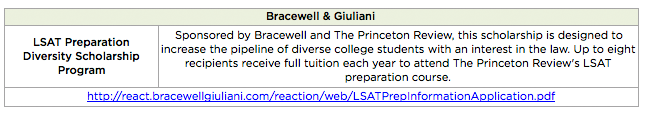

Law firms have long funded scholarships for college students to go to law school, but the move to help finance undergraduate work for lower-income minority students is growing at a time when the legal profession struggles with a lack of African-Americans and Hispanics in their ranks.

The increased costs of higher education, combined with the successful legal attacks on affirmative action programs, led to a significant decline in the number of minority students attending and graduating from law school in recent years.

While most of the college scholarship recipients will not go to law school, lawyers funding the scholarships and other efforts say it is a huge step toward increasing the number of minorities in the educational pipeline. They say it is an investment they hope will eventually end with students becoming highly paid law firm partners or corporate general counsels a couple decades down the road.

In fact, there is already evidence that some of the recipients have gone to law school and a handful of them are already practicing law.

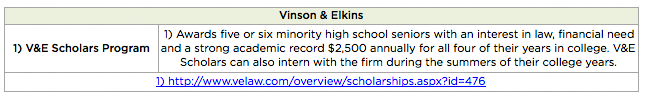

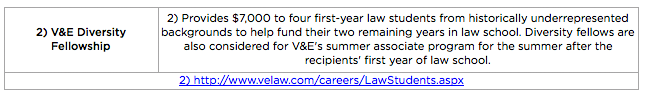

“If you’re looking at scholarships in law school, you’re looking too late,” said Jim Reeder, a litigation partner at Vinson & Elkins in Houston and head of the firm’s foundation that funds six scholarships annually and more than 100 scholarships during the past two decades.

“The success of the program is not measured just by how many became lawyers, but how many go through college and are off on their own and succeeding,” said Reeder, who notes that a handful of the students have become lawyers and corporate executives.

Reeder and Austin plaintiff’s lawyer Dicky Grigg, who are usually on opposite sides in court, agree that most of the scholarship recipients are unlikely to become lawyers.

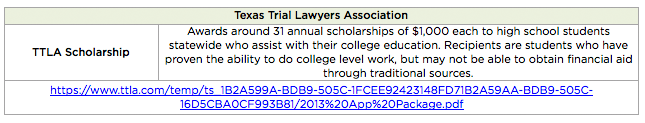

“Most of these kids are going to be teachers or social workers or business leaders, but the key is to make college a reality for them with the possibility that some of them will become lawyers,” said Grigg, who leads the Texas Trial Lawyers Association’s efforts to award $1,000 college scholarships to about 31 high school students annually – one for every state senate district.

“These are kids who work two or three jobs, babysit their siblings because mom or dad are not home, and they are fighting hard to keep their grades up,” said Grigg, who specializes in personal injury and business litigation. “They just need a little help and encouragement in showing them that college is a real option.

“Even if they don’t become lawyers, they certainly become more educated and informed citizens,” he said.

Those descriptions certainly describe Erbeyi, who was in her high school English class in 2004 when her teacher made a surprise introduction. A partner from V&E announced that Erbeyi had been awarded a $2,500 a year scholarship for four years and a paid internship at the law firm for the next four summers.

Erbeyi, who is now a project manager at Westar Trade Resources in Dallas, describes it as a life-changing moment.

“If I hadn’t received the scholarship, I would have gone to community college or not gone to college [at all],” said Erbeyi, who now has a bachelor’s degree from DePaul University in Chicago, a master’s degree from Georgetown and is considering going to law school.

The obstacles facing many low-income and minority teenagers go way beyond money and require personal attention and intervention.

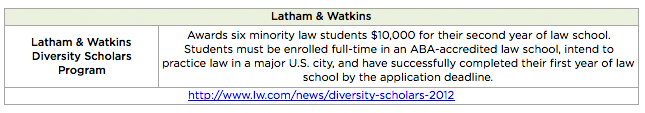

“Writing the check is the easy part,” said Michael Dillard, managing partner at Latham & Watkins in Houston.

Latham has teamed up with the Cristo Rey Jesuit College Preparatory School of Houston, a national chain of schools that provides a rigorous college prep education to students of low-income families, to be a corporate sponsor of the school’s Work Study Program.

As a sponsor, Latham’s Houston office hires about four students annually to work in the firm’s library, marketing, recruiting and records departments.

“It gives them an opportunity to see a part of corporate America that most of them would never be exposed to,” Dillard said. “It changes their perspective on what is possible.”

Glenn West, the managing partner of Weil’s Dallas office, even took matters into his own hands when he saw a story on the news this past summer about a graduating minority high school student from Lancaster who had an interest in pursuing a legal career. West personally reached out to the student and hired the rising college freshman as a summer intern for Weil.

Law firm leaders say that educators tell them that the key is reaching students earlier in their life, before they are in danger of straying from their dreams.

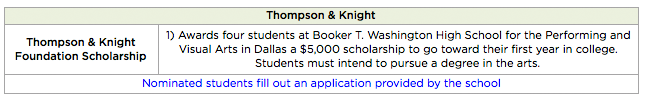

With that in mind, Dallas-based Bickel & Brewer created its Future Leaders Program in 2001 in an effort to expose Dallas public school students – fifth graders to seniors – to enhanced educational and cultural experiences.

The goal of the program, which currently involved more than 160 participating students, is to provide the same leadership and personal development opportunities afforded to students at elite private schools. See the Future Leaders Program at www.bickelbrewer.com.

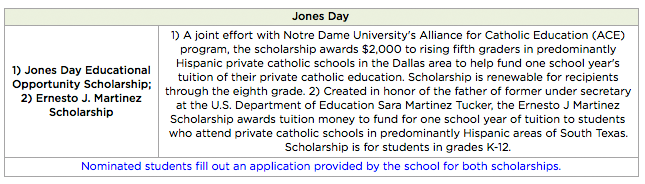

Similarly, the Dallas office of Jones Day created an educational scholarship effort that partners with Notre Dame University’s Alliance for Catholic Education (ACE) program to reach fifth graders attending private catholic schools in predominantly Hispanic regions of the Dallas area.

The program awards select students in need scholarships to help fund their school tuition. Recipients receive $2,000 each year that is renewable through their eighth grade school year.

“I look at my lifestyle and where I’m at and it’s all because of education,” said Jones Day IP litigation partner Hilda Galvan, who is the daughter of two parents who never finished high school.

“Education is the way out and these scholarships are ways for the students to find a better life for themselves” Galvan said. “Being able to give back is an important part of being a lawyer.”

The lawyers admit that the evidence of success in these efforts remains anecdotal, but they say that individual accounts are encouraging. Scholarship recipients have become lawyers, public school teachers and leaders at non-profit organizations.

Clifford Robertson, an African-American lawyer from San Antonio who has his dream job as an in-house attorney for the Children’s Medical Center of Dallas, thanks the Sarah T. Hughes Diversity Scholarship. The 2010 SMU Dedman Law School alum said he would not be able to work for a non-profit immediately after law school if he had graduated with large debts to repay.

“I think there are a number of law students who are out in the workplace now and they have to take jobs that they may not necessarily be passionate about, but they might pay more so they can pay their [law school] debt,” said Robertson. “A paycheck becomes priority over passion.”

© 2012 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.