HOUSTON — At the surface, a long-running dispute between Cheniere Energy and a fellow Houston-based natural gas competitor is over a $46 million transaction: whether it was a loan or an investment, whether an agreement that began with a handshake is binding or non-binding, and whether the deal was stolen by its founding CEO or was an opportunity the Cheniere board passed up when they fired him.

But in recent months, the convoluted litigation has made one thing abundantly clear: it’s not only about the money. It’s about bad blood between Cheniere and Charif Souki, the company’s founder and former CEO – now cutthroat rivals in the tight-knit global export of liquefied natural gas. That, and corporate raider Carl Icahn.

The case, which has touched down in five different courts over four years, will likely proceed to trial next week after a recent, last-ditch mediation made no progress and after a Houston state court earlier this month denied a request by Cheniere to postpone the trial.

Last month, the court granted Souki’s request to add 10 current and former members of Cheniere’s board of directors to the jury form, underscoring the personal animus now driving the litigation. It was a series of board actions four years ago that drove Souki from the company, taking with him what became a lucrative LNG project.

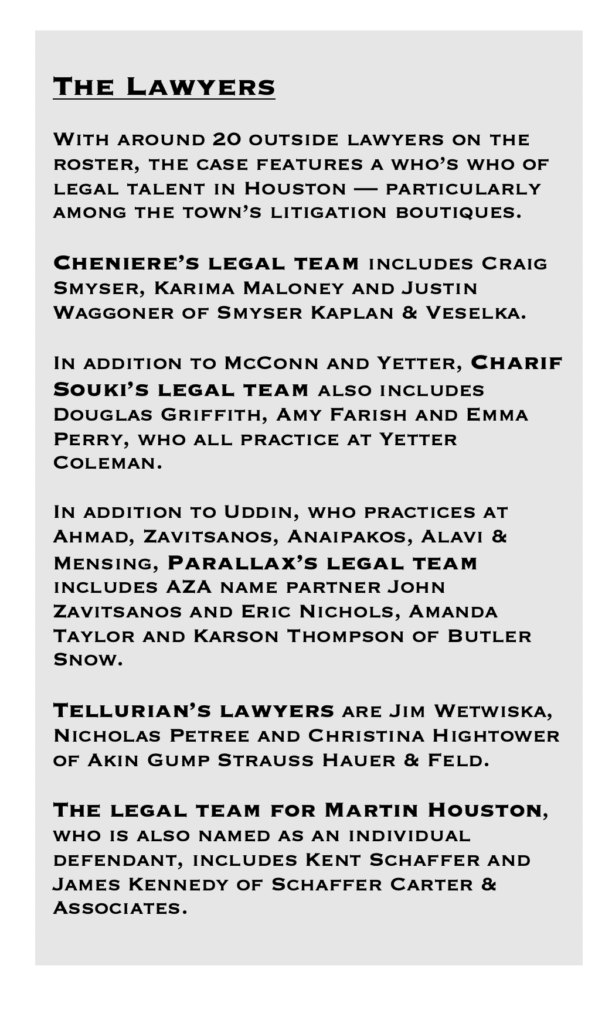

During those board meetings in December 2015 – from which Souki was mostly excluded – Cheniere decided to take the company in a “different direction entirely” in two very distinct ways, one of Souki’s lawyers, Paul Yetter of Yetter Coleman, told Harris County District Judge Fredericka Phillips during a Dec. 5 hearing.

First, Yetter said, the board members decided to essentially make Cheniere “a utility company instead of an entrepreneurial one.” And second: “they decided to fire their 20-year CEO overnight.”

Cheniere and its lawyers declined to comment on the litigation.

An Icahnic arrival

Souki was only added to the litigation as an individual party 11 months ago, but the circumstances that launched the legal battle have always revolved around him, the company he founded two decades ago and, behind the scenes, Carl Icahn.

The dispute dates back to 2014, when Souki and Martin Houston, a friend and respected executive in the LNG industry, entered talks to jointly develop a mid-scale LNG plant in Louisiana. Houston had recently retired from his role as chief operating officer of BG Group and had started a new company, Parallax Enterprises.

The idea, according to court documents, was for the new mid-scale project in Louisiana to complement other, larger-scale plants that Cheniere was already building. Souki presented the project to the other members of Cheniere’s board, who approved the project. Cheniere and Parallax ultimately agreed to jointly develop two LNG terminals: the Live Oak Project in Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana and the LLNG Project in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana.

Because the early pursuit of a possible LNG project can get quite expensive, Cheniere agreed to provide some financial assistance in exchange for Parallax doing the heavy lifting. Cheniere provided $46 million to Parallax, which, depending on who you’re talking to, was either a loan with an upcoming maturity date (Cheniere’s view) or advance project funding that Cheniere acknowledged it would not collect on (Parallax’s view).

Whether that agreement was binding is still in dispute. In his court filings, Souki says that Cheniere executive Anatol Feygin presented the project at a June 2015 board meeting, where he recommended the board to approve the joint development. According to Souki, the board unanimously voted to approve it, and Souki shortly thereafter reached an agreement on all material terms with Parallax and each party asked their lawyers to memorialize the transaction in writing.

Cheniere’s account is different. According to the company’s court filings, “it became increasingly clear” after looking into the project “for the better part of a year” that the project was “fraught with potentially insurmountable development obstacles.” At the end of 2015, Cheniere elected not to pursue the project with Parallax.

At the same time, the board also elected to oust Souki as CEO. That decision was largely influenced by Icahn, who had gobbled up nearly 14% of the company between August 2015 and Dec. 7, 2015. As Cheniere’s largest outside shareholder, Icahn gained two spots on the board that were subsequently filled by two Icahn Capital employees. Icahn later openly claimed responsibility as the driving force behind Souki’s ouster.

With any Icahn investment, tensions with current management are nearly always a given. Icahn values revenue-generation aimed at investor return. Management often focuses on long-term growth and development. And cash spent on projects like Parallax is often seen by Icahn and his allies as money better distributed to stockholders.

Cheniere explains in court documents that Souki needed to go because there was a growing disconnect between his vision for Cheniere’s future and that of the reconfigured board. The Parallax project was part of that growing disconnect, Cheniere explains, because it matched Souki’s desire to focus on further capital expansions versus the board’s desire to stick to revenue-generating operations.

Projects such as the Parallax JV “could create substantial additional risk for the company and its shareholders, while further delaying any prospect of a return to investors through profitable operations,” Cheniere says.

Souki alleges that Icahn’s board members, Sam Merksamer and Jonathan Christodoro, convinced two other Cheniere board members — Neal Shear and Andrea Botta — to help oust Souki in exchange for lucrative pay bumps and promotions. Then, Souki says, the board conducted a Dec. 8, 2015 meeting that excluded Souki, where they discussed his future at the company and ultimately decided to fire him as CEO, as chairman of the board, and as a board member. Cheniere officially terminated Souki as CEO on Dec. 12.

In keeping with Cheniere’s Icahn-influenced cost-cutting, the board also decided to cut the cord on the Parallax project.

Tellurian rises

As Souki sees it, Cheniere’s decision to drop the project with Parallax was problematic.

For one thing, Houston and his associates at the fledgling Parallax Enterprises had already sunk lots of time and money into the project. But more importantly, because of Souki’s position that material terms of the project had been reached, Cheniere and Parallax had already formed a partnership — fiduciary duties and all.

Souki says in court documents that he explicitly told Cheniere’s lawyers in a January 2016 interview that he would feel “morally obligated to help Houston get back on his feet” with the project if Cheniere decided to officially remove it from its company budget. Despite his protests, the company did so during a Jan. 21, 2016 board meeting.

On Feb. 23, 2016, Souki and Houston publicly announced the formation of their new company, Tellurian Investments, which essentially replaced Parallax. The announcement came a week and a half after Souki officially cut all ties with Cheniere by formally resigning from its board. Cheniere’s new rival proceeded to announce a project similar to the original Parallax project called the Driftwood LNG export terminal, located on the west bank of Louisiana’s Calcasieu River.

Investors quickly got behind the new venture. In a year’s time, Tellurian raised nearly $300 million — including $207 million from Total and $25 million from GE — and made its debut on the Nasdaq through its reverse merger with Denver-based Magellan Petroleum Corp. Executives who had worked with Souki at Cheniere began arriving at Tellurian’s doorstep in droves, among them Meg Gentle, who is now Tellurian’s CEO.

Today, the company has raised around $600 million for the Driftwood LNG project, which last month received approval from federal energy regulators to begin site prep work. According to Tellurian, the $27.5 billion project is slated to break ground next year and start producing its first batch of LNG in 2023.

The Parallax View

Compared to Tellurian’s quick, relatively straight-arrowed rise to success, the path of litigation that leads us to the upcoming trial in Houston state court resembles the hairpin turns of San Francisco’s Lombard Street, the “world’s most crooked road.”

In addition to Harris County’s 61st district court, the legal battle has made an appearance in Houston federal court, Louisiana state court, Houston’s Fourteenth Court of Appeals, and, most recently, the Supreme Court of Texas.

On Feb. 3, 2016 Cheniere sued Parallax to retrieve the $46 million it says was not an investment, but a loan. They offered as evidence the agreement between the two parties, memorialized in a secured note, which matured in December 2015, around the time Cheniere was considering the ouster of Souki and chopping the Parallax project from the company budget.

Parallax countered with a lawsuit against Cheniere in a Louisiana state court, alleging breach of fiduciary duty to develop the two liquefaction plants the parties had agreed to pursue. Cheniere removed the Louisiana state action to Louisiana federal court, where it was transferred to Houston federal court and consolidated with the original action Cheniere filed there.

But Parallax dismissed its lawsuit, and filed a new one in Houston state court in the summer of 2017, where almost three years later it is now scheduled for trial. But the stakes have now grown higher and the issues more complex.

Although the heart of the battle appears to be more personal, there is still a pretty penny at stake. Beyond the $46 million Cheniere seeks against Parallax, Parallax wants $400 million from Cheniere because of the development fees it says it missed out receiving as a result of Cheniere cutting the chord on their joint development. Parallax says Cheniere was to assume ownership of the LLNG Project and Live Oak Project after Parallax developed them to fruition and construction-ready. In exchange, Parallax said, Cheniere would pay it $200 million for each project.

Parallax also argues that it formed a legally-binding partnership with Cheniere under Texas law, which gives the litigation a modern flair of the epic Pennzoil-Texaco legal battle from the 1980s.

“You have two people on both sides of the handshake saying they made a deal to a set of terms, and we have written evidence of those terms,” said Monica Uddin, one of Parallax’s attorneys. “Most importantly, both sides of the deal said they made the deal and each side had the authority to make it. Hopefully the jury finds there’s no going back from that just because the process was halted abruptly as the lawyers were haggling out the details.

“It’s not a case where everybody was waiting for a 200-page contract to get drafted and signed; Cheniere had started funding Parallax,” she added. “Cheniere had put people and time into it and Parallax had put people and time into it. They were doing weekly meetings with engineering contractors, site studies, had secured land… and had met and announced the project with the governor of Louisiana. They were doing it and then Carl Icahn sort of upsets the apple cart.”

At various stages Cheniere has wanted to collect its $46 million, foreclose on Parallax assets now owned by Tellurian, and now is pursuing charges of tortious interference by Tellurian executives who, they say, began selling equity interests in projects that are now successful only because they were created by money provided by Cheniere.

In a countersuit filed in 2017, Cheniere alleged that Tellurian’s Driftwood project enjoyed such quick success due to the heavy lifting done when Parallax was pursuing essentially the same project — Live Oak — with Cheniere’s money.

“Tellurian thus saved itself hundreds of millions of dollars through its improper use of work product prepared for Parallax Enterprises at Cheniere’s expense,” Cheniere says in court documents.

Tellurian denies that, arguing that it never used any Parallax collateral to build its business, including its assets in the Driftwood project — and that the Driftwood project is different from the Live Oak project.

“These lawsuits originated from a disagreement between Cheniere and Parallax that occurred before Tellurian existed,” Joi Licznar, Tellurian’s SVP of public affairs & communication said in a statement. “The accusations against Tellurian are puzzling and have no basis. This case is just a distraction, it is not significant to us. We are focused on building our business.”

Though trial has not begun yet, Parallax and Cheniere have already tangoed in the Fourteenth Court of Appeals (twice) and the Texas Supreme Court over whether Cheniere could initiate foreclosure proceedings on the interest Parallax has in subsidiary Live Oak LNG, which is also a party in the litigation.

In December 2018, a three-judge panel on the court of appeals overturned an injunction that stopped foreclosure proceedings, but in an en banc review last year, the full panel did a 180, reinstating the injunction for Parallax. In late October, Cheniere asked the Texas Supreme Court to grant review.

The high court is yet to officially grant review, but on Jan. 10 it ordered Parallax to provide a response to Cheniere’s petition by Feb. 10, which increases the chances of the Supreme Court taking the case. Due to the development, Cheniere asked Judge Phillips to continue the trial indefinitely until the case in the Supreme Court unfolds, but she denied that request Jan. 17 at a pretrial hearing. It marked the fourth time for Cheniere to try to delay the trial date. Three days later, Cheniere filed an emergency motion with the Supreme Court to stay the case, arguing that the high court “is currently considering issues that could fundamentally alter how the trial is conducted.”

Beyond the tango up the appellate latter, Cheniere’s legal bills appear to also be growing horizontally. Earlier this month, Cheniere investor Mel Gross filed a separate derivative shareholder lawsuit in another Harris County district court against the current members of Cheniere’s board. Gross alleges that the board members breached their fiduciary duty to the company by failing to conduct their due diligence before deciding to terminate the Parallax project, which caused the company to incur significant legal expenses as a result.

Citing heavily from the claims laid out in the existing legal battle, Gross alleges that each board member instead “chose to put their personal and Icahn’s selfish interests above the interests of the company.” The board members have yet to respond to the new suit.

The Souki saga

But the most explosive chapter in the litigation was launched last February, when Cheniere sued Souki as an individual defendant. Since that point the business dispute has become personal.

Cheniere alleges, in essence, that while Souki was still at Cheniere, he breached his fiduciary duties to the company by secretly pursuing the Parallax/Tellurian opportunity — a competing opportunity — for himself while spending Cheniere’s money to develop it.

Moreover, Cheniere says Souki entered multiple “key-man” provisions in Cheniere’s agreement with Parallax without the board’s approval that would allow him to control the projects if Souki left Cheniere.

Even before Souki approached Cheniere’s board about a potential project with Parallax, he and Houston considered the option of Souki pursuing the opportunity individually instead of through Cheniere, the company says in court documents. To conceal this, Cheniere says, Souki asked Houston to correspond with him through his personal email instead of his work email.

And while Souki was still a Cheniere director in January 2016, Cheniere says Souki and Houston fraudulently transferred Parallax assets to an entity that later became Tellurian —fraudulent because those assets were largely the $46 million Cheniere is rightfully owed.

“In effect, Souki had come full circle: Through Tellurian, he was again personally pursuing the same project his friend Houston presented to him in 2014 — only he was able to do so with the benefit of tens of millions of dollars of work funded with money loaned by Cheniere, which Souki and Houston had no intention of paying,” Cheniere says in court documents.

Cheniere says it discovered Souki’s alleged misconduct through discovery produced in its underlying case against Parallax and Tellurian. In it, there was a privilege log produced by Tellurian that identified a number of communications between Souki, Houston and other Parallax principals in January and February 2016, while Souki was still on Cheniere’s board.

“Souki’s participation in ostensibly privileged and confidential communications with the principals of a party with interests antagonistic to Cheniere, and against which Cheniere had initiated litigation, is anti-ethical to the fiduciary duties Souki owed Cheniere at the time of the communications,” Cheniere says.

But in his equally-explosive response, Souki argues that he was blatantly upfront with Cheniere the whole time, and was never challenged when he informed the board of his post-termination plans.

“To put icing on the proverbial cake, Cheniere and the directors also conspired to mislead Souki into believing that he could pursue abandoned projects that Cheniere and its board had duped under Icahn’s plan,” Souki says in court filings.

He also challenged Cheniere’s motives in the litigation, since it waited three years to sue him while “watching Souki invest millions of dollars in his own money into his new LNG venture with Houston.” Souki argues Cheniere only sued him after he achieved success at Tellurian.

“The reason why we think this has become so personal is because Cheniere is embarrassed by a very precipitous and rash decision that the company and its board made at the end of 2015,” Tim McConn, one of Souki’s lawyers, told The Texas Lawbook. “Charif was willing to go his separate way, start his new company and let bygones be bygones, but now they’ve come after him and want him to pay $46 million on top of all the other damages that Charif has allegedly caused. He’s not going to succumb to the blackmail or extortion.”

Souki also argues Cheniere sued him only to intimidate him before a scheduled deposition in the underlying dispute with Parallax.

“Hoping he would deny any deal with Parallax, Cheniere alleged such a deal would have breached Souki’s fiduciary duties to the company,” Souki says in court filings.

Moreover, Souki also argues that Cheniere had already demonstrated that it no longer considered him a director or fiduciary as of Dec. 13, 2015, the day after they fired him.

Souki says Cheniere’s intent on this topic is proven by what the board did beginning Dec. 8, 2015. For starters, he says, the other board members excluded him from participating “meaningfully or at all” in multiple board meetings. Souki says they also withheld company information from him, disabled his company iPad and iPhone so he could not access important company information, and never sent him minutes of the board meetings he was excluded from. He argues that all of the board’s actions were done in violation of Delaware law.

McConn said Souki is eager for his day in court.

“Charif is very much looking forward to taking the stand and telling his side of what happened between him and Cheniere, and Martin and Tellurian,” McConn said. “He is very excited about the possibility of getting on the stand and answering the questions both from his own lawyers and Cheniere’s lawyers.”

Uddin, the Parallax lawyer, said Souki and Houston will be the most important witnesses at trial.

“They were the hands in the handshake,” she said. “The most important fact is that they agreed to and are unanimous that they reached this agreement between the two of them on the distinct, cognizable set of material terms. They’re the terms the Cheniere board reviewed in writing and approved, so I just don’t think there’s any way for Cheniere to renege or wriggle out of the deal.”