Bill Kroger has been a music lover his whole life. As a young boy in Houston, he’d spend lots of time working in the music stores that his parents owned. He even became an acquaintance of ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, who visited the store multiple times and gave the young Kroger albums and T-shirts, and introduced Kroger to another favorite musician, Sam “Lightnin” Hopkins.

Now an energy litigation partner at Baker Botts, Kroger has made significant progress on what he describes as “by far the most important work I’ve ever done in my life.” Last week, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History announced that it has accepted a massive blues and folklore archive — including Hopkins material — gifted by Baker Botts client Susannah Nix, the daughter of the late prominent folklorist Robert “Mack” McCormick.

The development with the Smithsonian is the culmination of five years of pro bono legal work by Kroger and Baker Botts intellectual property partner Roger Fulghum totaling more than 1,000 hours. The legal work entailed talking with other organizations that expressed interest in the archive, advising Nix, drafting and negotiating agreements with the Smithsonian once it became the frontrunner, and working through some complex copyright issues.

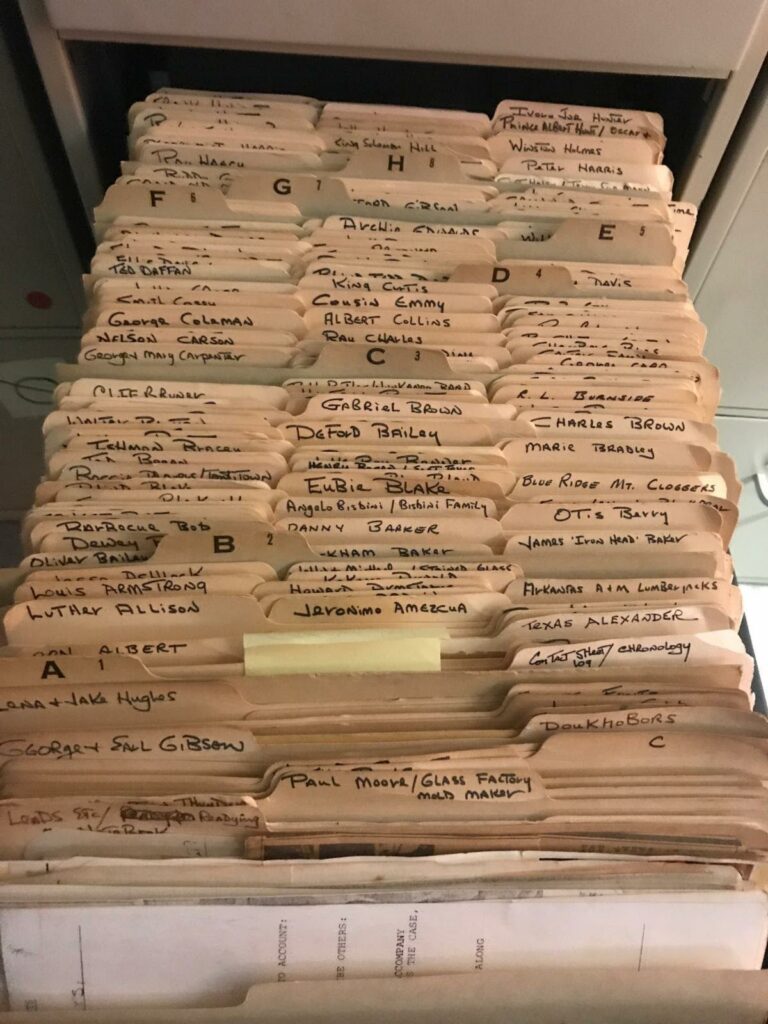

The archive, which the lawyers estimate is worth hundreds-of-thousands of dollars, includes unreleased recordings, photographs, interview tapes, research notes, correspondence, essays and other materials pertaining to Texas and Southern music and folklore. The collection also includes materials from McCormick’s years managing the careers of famous Texas musicians, including Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb; correspondence with musicians and other folklorists like Pete Seeger and Alan Lomax; and research on the lives of important musicians like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Robert Johnson.

McCormick began documenting and collecting material in the 1950s, and continued his research and collecting even as he battled mental illness later in life. He died in 2015 in his home in Houston.

Kroger pointed out that McCormick’s work is important because much of the archive involved music by African American artists and material about “African American life, folklore and stories of Black artists” such as Black fiddlers, banjo players, Black cowboy music and early Black marching bands.

“He wanted to figure out where [the music] came from,” Kroger said of McCormick. “He recognized the beauty and magic of it at a time when very few people in Houston, let alone Texas, appreciated it. If you go back and look at segregated Texas, there was a rich cultural life. It’s the music that the grandparents and great-grandparents of a lot of people in Texas would have [listened to], and it also explains how did Texas become Texas?”

Nix told The Texas Lawbook that her father worked for several years at the Smithsonian and that she heard about it often growing up before seeing it for herself as a high school student.

“To have an entire archive and his life’s work there is just really beyond my wildest dreams,” Nix, a romance novelist, told The Lawbook. “It’s in the best possible place. I wanted it to be available to the public, and people have been really eager to see and explore some of this information.”