© 2015 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden

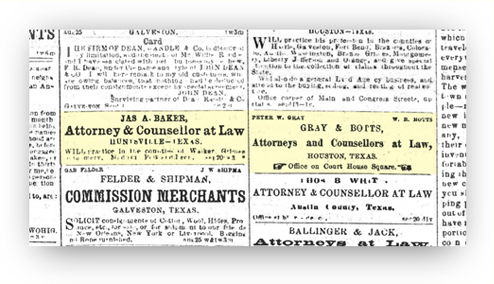

HOUSTON (Nov. 12) – Two advertisements side-by-side in the Houston newspaper promoting separate law firms should have been a hint that a big merger was in the works.

After all, law firm mergers were all the rage of that day.

That particular day was Oct. 20, 1865. The newspaper was the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph. The law firms were Gray & Botts and Jas. A. Baker.

In the decades that followed, lawyers at Gray, Botts & Baker – later renamed Baker Botts – were at the center of some of the biggest political and business events in the history of Texas and beyond. Today, it is considered one of the premier energy law firms in the world.

Baker Botts, with 725 lawyers, is the oldest and largest law firm based in Texas. Its lawyers became chief justices, federal judges and even a Secretary of State. The firm has represented a handful of clients, including CenterPoint Energy and the Rice family trusts, continuously for more than a century.

About 400 lawyers, business leaders and dignitaries will gather Thursday evening in the Julia Ideson Building of the Houston Public Library to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Baker Botts.

“This is much more than just throwing a party,” says Baker Botts managing partner Andrew Baker, a corporate lawyer who offices in Dallas and Houston.

The guests at tonight’s reception will be able to examine original documents throughout the law firm’s 175-year history, including Peter Gray’s signature on a deed to purchase property for the Republic of Texas in 1839. There are handwritten ledgers from the 1870s showing how much clients paid and minutes from partner meetings in the 1880s where Baker and Botts decided how much each other would be compensated.

In fact, Gray was the primary founder of the Houston Public Library in 1848.

“We have put together an unbroken record of our firm’s legal work dating all the way back to the Republic of Texas,” says Baker Botts partner Bill Kroger, who co-chairs the firm’s energy litigation practice and is its official historian.

For the past year, Kroger spent hundreds of hours mulling through thousands of old boxes Baker Botts housed at the Iron Mountain storage complex.

Kroger found original handwritten notes, letters and memos detailing the firm’s representation of Howard Hughes in 1920 in an intellectual property dispute involving a tool bit and its work for legendary Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey who worked with a group that owned a local baseball team called the Houston Buff.

“There is this view of Big Law that is impersonal and, as you will discover, that’s just not who we are,” Kroger says. “These documents show lawyers learning their craft. But it is much more than just telling romantic stories about the past.”

In a world where the life expectancy of a Fortune 500 company is now 15 years, according to the American Enterprise Institute, the story of Baker Botts is truly extraordinary.

“The history of Baker Botts is the history of Texas,” says Pat Stanton, a partner who heads the real estate law practice in the firm’s Dallas office, which is celebrating 30 years in operation. “I think everyone here is keenly aware of our firm’s role and the important work that Baker Botts lawyers have done over the years.”

The firm traces its origin to Peter Gray, a Virginia native who moved to Texas in 1837 with his lawyer father, who represented East Coast lenders helping to finance the Republic of Texas.

In 1846, Gray authored the state’s first rules of civil procedure, which are the guidelines that judges and lawyers use to govern civil lawsuits and trials. The rules included 158 sections in 45 pages. Today, those same rules occupy 300 pages covering 822 sections.

A year later, Gray voluntarily represented an African-American woman named Emeline, who was wrongfully enslaved by a white man. Gray convinced a dozen white jurors in Houston that his client should be set free.

When Texas seceded from the Union during the Civil War, Gray became a representative in the Congress of the Confederacy. He also served as a Secretary of the Confederate’s treasury and his name was printed on Confederate currency.

In 1865, President Andrew Johnson pardoned Gray, who had been disbarred as a lawyer because he joined the Confederacy.

In 1872, James A. Baker, a former Texas judge, joined the pair.

Gray, Baker & Botts generated $26,000 in revenue in 1874, according to the original financial ledgers, which feature handwritten entries of every bill paid by clients and every dime spent by the lawyers over several decades. Last year, Baker Botts reported $653 million in revenues.

The firm’s first major client was Texas Pacific Railway, which paid the lawyers $7,356.25 for its legal services in 1879. Within a couple years, Baker & Botts represented nearly all the railroad companies.

In 1878, Judge Baker’s son, James, joined the firm. Kroger, the Baker Botts historian, says James A. Baker, aka Captain Baker, was the most influential person in the firm’s history.

Baker Botts entrance into the energy sector came in 1882, when newly created Houston Light & Power hired the firm to handle nearly all of its legal work, including its 1905 franchise agreement with the City of Houston.

HL&P is now CenterPoint Energy, which is still a Baker Botts client to this day.

“We knew Baker Botts knew our company and how we do business and how we wanted to be perceived,” Rozzell says.

When Botts died in 1894, Captain Baker took over the representation of William Marsh Rice and his family. Baker did all the legal work setting up Rice’s trusts, which he intended to go to start a university in Houston. Rice made Baker the executor of his estate, which was valued at $4 million in 1893.

In 1900, Rice died in New York, where a new lawyer claimed that Rice had signed a new will that diverted the money to his control. But Captain Baker conducted a thorough investigation, discovering a conspiracy in which the butler killed Rice and the lawyer had falsified various documents, including the new will.

The firm’s fortunes spiked again on Jan. 10, 1901, when tens-of-thousands of barrels of oil spewed out of the Spindletop dome near Beaumont. The Texas oil rush was on and Baker Botts represented several major oil companies, including Sinclair Oil.

Today, Baker Botts represents Exxon Mobil, Shell Oil, Halliburton and many other large corporations in the oil and gas sector.

In 1942, Baker Botts faced its first major crisis with the start of World War II. The U.S. military drafted exactly half of the 40 lawyers practicing at Baker Botts. The firm promised all its lawyers that they would have their jobs when they returned.

Fortunately, none were killed in action and some were allowed to return to Houston earlier than planned when the U.S. War Commission officially declared working at Baker Botts “an essential activity.”

One of the firm’s partners, Baine Kerr, was wounded when he sailed with the 6th Marine Regiment for Guadalcanal. After he recovered, Kerr participated in the Marine’s amphibious assaults in Saipan and other countries in the Western Pacific.

When Kerr returned to Baker Botts, he became a lead lawyer for Pennzoil Co. He also handled Schlumberger’s first public offering in 1961.

In 1957, Baker Botts faced another big decision. James A. Baker, III was graduating from the University of Texas. He applied to the firm, hoping to be the fourth generation of James A. Bakers.

“When I was growing up, the only job I ever wanted was to be a lawyer at Baker Botts, like my father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather,” Baker III says.

There was a problem. The firm’s leadership had implemented a no nepotism rule.

“The firm actually took a vote on whether they should make me an exception, but the partners voted no,” Baker says. “I was broken-hearted. I thought my legal career was over.”

Instead, Baker joined Andrews Kurth, where he practiced for 22 years before going into public service. He was Secretary of the Treasury under President Reagan and Secretary of State under President George H.W. Bush.

In 1993, he decided to go back to law. Again, he applied at Baker Botts.

“The partners rewrote the nepotism rule so that if your last name is already in the name of the law firm and if you have been secretary of state, then you are exempt,” he says laughing.

Baker and his son, James A. Baker IV, who joined the firm in 1985, will be the center of attention at Thursday night’s 175th celebration.

Baker III made headlines again in November 2000 when he was hired by then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush to lead the legal team in the election fight that later became known as Bush v. Gore.

Baker Botts has been involved in many other historic matters. For example, the firm was co-counsel with Joe Jamail representing Pennzoil accusing Texaco of illegally interfering in a proposed merger with Getty Oil. In 1985, the jury awarded Pennzoil $10.5 billion, which is still the largest verdict ever upheld in the U.S.

The firm also has been involved in some of the largest corporate mergers of all-time, including representing Mobil Oil in its $82 billion merger with Exxon in 1999.

In fact, Baker Botts is currently advising Halliburton in its $35 billion acquisition of Baker Hughes – a deal that was announced last year and is waiting final approval.

“The history of Baker Botts demonstrates its great leadership and ability to change,” says Halliburton General Counsel Robb Voyles, who is a former Baker Botts partner. “The firm started as a railroad law firm and then became an energy law firm, and now it is also a technology law firm.”

Voyles is referring to Baker Botts decision two decades ago to build a technology and intellectual property practice. It now has more than 150 lawyers who handle IP law matters, which is by far the largest in Texas.

“We don’t practice like we did at the end of the Civil War, or at the end of the Depression or at the end of World War II,” says Andy Baker, the firm’s managing partner. “We have literally re-invented every aspect of our firm and its operation so that we can provide maximum value to our clients.

“The goal for the partners at Baker Botts is to leave the firm better than when we arrived,” he says.

© 2015 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.