As a summer associate among other high achievers at Vinson & Elkins’ office in Austin nearly 20 years ago, Jimmy Blacklock stood out as strikingly bright. He also was wired a bit differently, showing more interest than most of the other new lawyers in large themes about the development of the law and administration of justice.

That is how Christopher V. Popov remembers the intense Yale Law student, now newly named as chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court

“His path to the judiciary makes total sense,” said Popov, who now heads the firm’s complex commercial litigation practice. “We’re working our heads down on a case and it’s Party A versus Party B and we’re thinking about how do we win this case, and he was always more interested in bigger-picture issues.”

“I think his heart was much more in public service and with the administration of law. These are more macro issues than the kind of stuff that you necessarily deal with as a private litigant,” said Popov, who expects Blacklock to be an excellent chief justice.

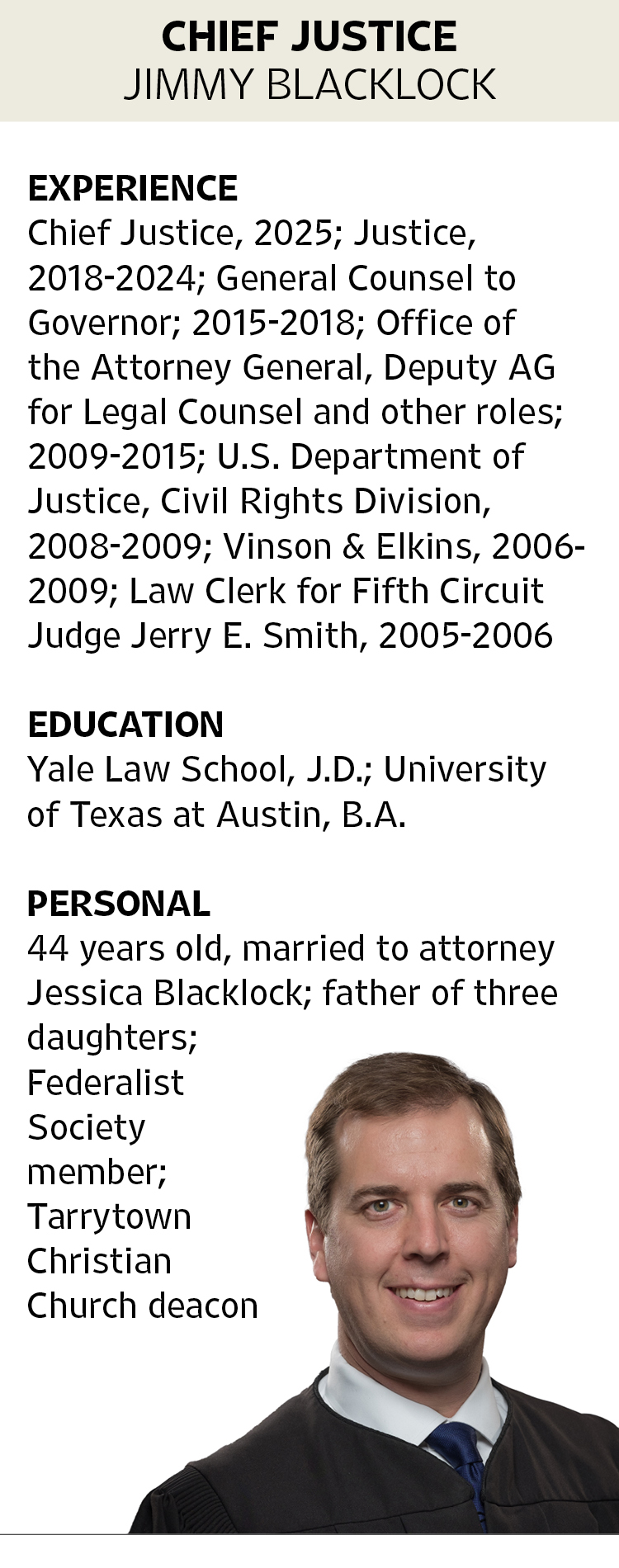

In selecting Blacklock for the leadership role, Gov. Abbott elevated a constitutional originalist and social conservative. The 44-year-old jurist is well known to Abbott, who made Blacklock his first appointee to the Supreme Court in January 2018. Blacklock came to the court from his position as the governor’s general counsel for three years after his six years working for Abbott at the AG’s office.

As deputy attorney general for legal counsel, he oversaw the open records and opinions divisions. In the Jan. 6 news release naming Blacklock to replace Nathan Hecht as chief justice, Abbott highlighted Blacklock’s six years in the AG’s office “where he assisted on Obamacare litigation, religious liberty, and right to life issues.”

Over his eight years on the court, Blacklock has proven to be a diligent justice, authoring over 100 opinions. He’s often blunt in his writing, pointing out legal theories he finds lacking. He tends toward the practical rather than finer legal points in questioning counsel during oral arguments.

Blacklock has not hesitated in some of his opinions to criticize executive branch agencies that he once worked for. Outside of the court, he has panned state and local government pandemic orders that closed houses of worship and prevented people from peaceably assembling.

Blacklock has an easygoing demeanor, whether he is talking to a Federalist Society audience of law students about the constitutionality of pandemic restrictions, fielding questions about his judicial philosophy at the Republican Party of Texas convention or being interviewed about his favorite flavor of ice cream by the children of a judicial colleague.

Abbott administered the oath of office to Blacklock Jan. 7 in a private ceremony that also included the swearing in of James P. Sullivan as the justice replacing Blacklock. Sullivan has served as the governor’s general counsel since November 2021.

The new chief justice declined an interview request from The Texas Lawbook. He said through the court’s spokeswoman that he has decided to decline media interviews while he is transitioning into his new position.

Dark Horse Candidate

Some court watchers expected Abbott to elevate one of his four other Supreme Court appointees, all of whom have the more traditional background as big firm partners and experience on the intermediate courts of appeals.

Paul W. Green, who served with Blacklock for nearly three years on the Supreme Court before leaving for private practice, was one of those expecting a different outcome.

“I thought that the chief was going to land somewhere else with the governor, but he’s a good choice. I think that the court will take to him as well as he will take to the job very easily. He’s got a good temperament for it, so I think he’s going to do great,” said Green, a partner at Alexander Dubose Jefferson.

Green said that his law partner, Wallace B. Jefferson, had served on the Supreme Court for about half as long as Blacklock when he was named chief justice in 2004 by then-Gov. Rick Perry. And, he noted, Tom Phillips was a relatively unknown district judge when he was tapped by then-Gov. Bill Clements to lead the high court in 1987.

“Give him a chance,” said Green, who was elected to the court in 2004 and served until retiring in August of 2020. “Jimmy has been there long enough. He understands how things work.”

Green said he was curious how Blacklock’s initial lack of judicial experience would play out when he first joined the court. He found the new justice quick to figure out how things worked after a bit of freshman hazing.

It was Blacklock’s first oral argument session, and the justices had “robed up” in preparation to enter the courtroom when a straight-faced Green told Blacklock that it was court tradition for a new justice to lead the court in the court’s official song.

“He had a shocked look on his face and then recovered quickly and said, ‘Why don’t you sing it for me,’” recalled Green.

Busy First Week

The first full week of Blacklock’s tenure has been a busy one, with three days of oral arguments and Tuesday’s swearing in of state senators as the biennial legislative session begins. Later in the session he will deliver the court’s legislative priorities, which are likely to include higher judicial pay and funding for legal services.

He is expected to differ from Hecht and other previous chief justices who bemoaned the partisan election of judges in their State of the Judiciary messages to the Legislature. Blacklock told the conservative news outlet The Texan last summer that he will not criticize judicial elections as much as others have done.

Blacklock easily won re-election to his position as justice last November. He raised $973,000 for his race, according to Transparency USA. Top donors were the Vinson & Elkins Texas PAC at $50,000 and Texans for Lawsuit Reform PAC at $40,000.

In a campaign event in Longview last October, he described his judicial philosophy, as reported by the Longview News-Journal.

“It doesn’t matter if you have a conservative governor. It doesn’t matter if you have a conservative Legislature,” Blacklock said. “If the courts are in the hands of people who think that the Constitution is a living document that changes and evolves with the times, whenever the judges decide that it should change and evolve, then the judges have the power to undo everything that the other branches do and to essentially take control over the government.”

Blacklock, a Houston native, received a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Texas and a Juris Doctor from Yale Law School. He is married to Jessica Blacklock, who practices at the small firm of Potts Blacklock Senterfitt. The couple have three daughters.

According to his 2024 Personal Financial Statement filed with the Texas Ethics Commission, the Blacklocks have extensive mutual fund holdings but no stocks, bonds, notes, gifts or trust income. He lists an outstanding student loan debt between $20,000 and $50,000.

Practical Questions, Sharp Writing

After three years at Vinson & Elkins, Blacklock began his career in public service with a stint at the Justice Department under President George W. Bush before joining the state AG’s office in 2009.

His decisions at the Supreme Court have been largely in lockstep with his conservative colleagues. In split decisions, he was most likely to agree with Justice Evan Young and least likely to agree with Justice Jeff Boyd.

Blacklock wrote the 2023 plurality opinion in Gregory v. Chohan, a closely watched case that could have seen radically new standards set for tethering noneconomic damages to the evidence in wrongful death and personal injury cases. The court ordered a new trial on noneconomic damages for a trucking company and driver involved in a fatal crash.

That same year he dissented from a 7-2 ruling that public universities have degree-revocation power. “Our Constitution establishes courts, not universities, to adjudicate disputes about ownership and possession of property,” he wrote.

His questions from the bench often focus on the real-world aspects of a case, such as when he pleaded with both sides during arguments in a contentious “wrongful pregnancy” case to use their daughter’s initials rather than her full name.

Hearing arguments in May 2020 in a long-running, bitter dispute over a doctrinal schism in the Episcopal faith and $100 million in church property, Blacklock expressed his agony over the case.

“Is there no one to whom both sides can go — someone with standing in the eyes of both groups to decide this in Christian love and charity — instead of the cold hard rules of the law we’re obliged to follow here?” he asked.

Blacklock can be scathing in some of his opinions. Last September, in a concurrence to the court’s denial of the state’s request to stop a firearms ban by the State Fair of Texas, he chided the attorney general’s position that the fair’s gun policy wouldn’t be enforceable if Dallas police are prohibited from enforcing it. “To the extent the state advocates for such an ill-conceived half-measure, it does so unadvisedly,” he said in a footnote.

In a 2019 concurrence to a per curiam decision reproaching the Texas Health and Human Services Commission’s treatment of a group home employee who was about to be placed on a state misconduct register, he accused the state agency of incompetence and duplicity.

“People already have plenty of reason not to trust their government. Apparently now the government agrees it shouldn’t be trusted. And it invites this Court to say that those who do trust the government — even to know its own administrative procedures — may forfeit their right to judicial review of the government’s deprivation of their liberty. The Court rightly rejects that invitation,” he wrote.

Blacklock wrote a concurrence last June in a closely watched case that upheld a law banning certain medical treatments for transgender minors. He said the judicial branch is not obligated to adopt the “Transgender Vision” over the “Traditional Vision” of gender.

“In fact, if our constitutional heritage reflects one moral vision or the other, it is most certainly the Traditional Vision, the vision held by all those from whom we inherited the Texas Constitution,” he wrote.

Green said he expects Blacklock will “get the work done, keep the trains running on time,” but may not initially have the influence on other members enjoyed by Hecht over his 35-year tenure.

“I think in Nathan’s case he’d been such a longtime court member, and everybody respects him so much, I think sometimes he would tip the scale of some of the cases,” Green said. “I don’t know that Jimmy will have the degree of influence yet, but it may eventually turn that way.”