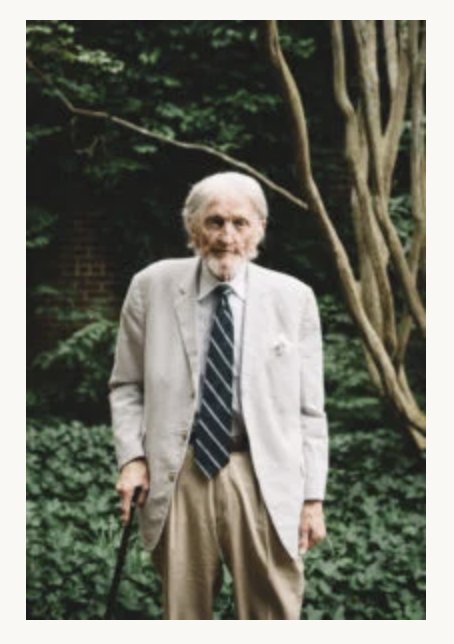

Bobby Lee Cook (1925-2021)

Seventy-two years ago, Bobby Lee Cook gave his first oral argument in a murder case.

Cook’s client had killed a man who had called him a “goddamn son of a bitch.” The prosecutor told jurors that calling someone a GDSOB was bad and worth a “good whipping, but not a killing.”

Because this was his first big jury trial, Cook had handwritten his opening statement. It was nine pages long. Standing in front of the jury, he read the first paragraph.

“I have a question for you,” he asked the dozen North Georgians in the box. “What would you have done if someone had called you a goddamn son of a bitch?”

An old mountain man with a long beard sitting at the back of the jury box didn’t wait for Cook to get to his second paragraph.

“Why, I would have killed the son of a bitch,” the juror said.

Cook looked up at the man, looked at the jurors, nodded, walked back to his chair and sat down.

“Lawyers must know when it is time to sit down,” Cook told me years later.

The next day, the jury acquitted his client.

Bobby Lee Cook, a legendary trial lawyer who legal scholars have compared to Clarence Darrow, died Friday at his Georgia mountain home. He was 94.

Over seven decades, Cook defended suspected criminals and prosecuted corporate desperados through civil litigation across the U.S. He represented defendants in more than 300 murder trials, and 80% of them walked free. His clients included moonshiners, bank robbers and politicians. He took more than a dozen cases to trial in Texas. The 1980s TV show Matlock was based on his life.

His defense of Savannah socialite Jim Williams helped bring to life John Berendt’s true-crime classic Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

“I pity the prosecutors and prosecution witnesses who have faced Bobby Lee,” famed Texas trial lawyer Richard “Racehorse” Haynes told me in an interview in 2015. “Bobby Lee’s presence in the courtroom was extraordinary. Jurors and judges were captivated by him.”

In 2009, the ABA Journal paid me to write in-depth profiles of seven of the greatest American trial lawyers who were still alive. One was Racehorse Haynes, who died in 2017. Houston trial great Joe Jamail was another. He died in 2015. Nashville’s James Neal, who prosecuted Jimmy Hoffa and the Watergate trio of H.R. Haldeman, John Mitchell and John Ehrlichman and defended Elvis’s doctor and Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards, died in 2010.

Cook is the fourth of the seven to die.

As a lawyer/journalist, I have covered hundreds of trials and thousands of court hearings. But when it comes to being a pure lawyer in the courtroom during a trial, Bobby Lee Cook is the best there has ever been.

“I still love getting up every morning and thinking which rich or corrupt businessman or politician am I going to kick in the goddamn teeth today,” Cook told me in a phone conversation in 2016.

Born into a poor family in North Georgia, Cook paid his own way to college. He went to law school at Vanderbilt, but he took and passed the bar before he graduated under the old “read law” program.

“He represented labor union organizers when no one else would,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution legal writer Bill Rankin wrote Friday in an article announcing Cook’s death. “He counseled the Rockefellers and the Carnegies. And, with a fearless, fiery resolve, he won far more trials than he lost, all the while radiating the charm of a well-read, nattily attired country gentleman.”

Cook told me that he made about $1 million a year.

In the mid-1980s, he was having breakfast at a rural Georgia diner when a longtime friend approached his table to ask how he could represent a local man who was accused of killing four people.

“I explained the Sixth Amendment, right to counsel, innocent until proven guilty, right to confront your accuser,” says Cook.

The friend gave Cook a puzzled look. A few days later, another longtime friend approached Cook, also seeking an explanation of how he could defend such a horrible person.

“I could tell you that it is the right to a fair trial, due process, effective assistance of counsel, but there’s more to it than just that,” Cook told his friend. “The guy paid me $150,000 in cash up front.”

“Well goddamn, Bobby Lee,” the man responded. “That’s great. We hope you win.”

Cook told me that there are two critical elements for a lawyer to win a murder case.

“You need to show the jury that the victim was a bad person who deserved to be killed, and then you need to show the jury that your client was just the man for the job,” Cook told me. “If you prove those two things, nine times out of 10, your client walks.”

The national media spotlight focused on Cook in 1975 when he represented on appeal seven men accused of killing Atlanta pathologists Warren and Rosina Matthews.

The key witness in the case — “Hell, the only witness,” says Cook — was Deborah Kidd, who testified that she witnessed the defendants murdering the couple. Kidd had been given full immunity by prosecutors if she agreed to testify against the seven.

Court after court rejected arguments that the seven men were innocent. But Cook turned things around in a federal habeas proceeding when he was able to put Kidd under oath one final time. The seven were days away from being put to death in the Georgia electric chair.

On the witness stand, Kidd recited her testimony as she had done many times. But Cook had unearthed new evidence – a personal check Kidd had written and cashed in South Carolina on the very day she claimed she watched the defendants committing murder. Kidd claimed the check was a forgery, but Cook presented three handwriting experts who swore the signature was hers.

When Kidd said she’d backdated the checks, Cook presented witnesses who said Kidd gave them the checks in South Carolina the day she claimed she was in Georgia. In addition, Cook presented evidence that Kidd and the lead detective in the case slept together during the investigation and trial.

“You are lying, Miss Kidd, you are lying,” Cook yelled out across the federal courtroom.

In tears and her body shaking, Kidd suddenly blurted out that she had made up the entire story, and that she and the police had framed the seven defendants. The convictions were reversed.

“If you can railroad a bad man to prison, you can railroad a good man,” Cook said. “That’s why we should always vigorously fight for the constitutional rights of even those who are most despised in our communities.”

For two weeks, I accompanied Cook from courthouse to courthouse across the South. The stories of his experiences were extraordinary. At points, it didn’t even matter if they were true.

At the end of the day, Cook’s success can be attributed to his understanding of the jurors in his cases.

In the late 1970s, Cook defended a man facing the death penalty in a rural and conservative town. In closing arguments, Cook decided to quote William Shakespeare in hopes of seeking compassion and leniency from the jury.

“The quality of mercy is not strained. It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven, upon the place beneath. It is twice blessed: It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.”

Cook started to attribute his quote to Shakespeare when he caught himself.

“I realized that I was in Dade County, Ga.,” Cook told me. “The people of Dade County are good but simple people. They don’t know who the hell William Shakespeare is. They may think he’s some guy named Bill from Tennessee, or worse from Alabama, and sentence my client to death.”

Cook cleared his throat and told jurors, “And that’s from Song of Solomon in the Bible.” The jurors all nodded in reverence.

That night, Cook was awakened in the middle of the night by a phone call from the prosecutor in the case, Bill Self, who said he had just finished reading through the Song of Solomon for the fourth time.

“What you told the jury ain’t in there, you son of a bitch,” the district attorney said.

“What version of the Bible are you reading?” Cook asked.

“The King James Version,” the prosecutor responded.

“I never said it was the KJV,” Cook replied and then hung up.

“The next day, the jury spared my client’s life,” he says.