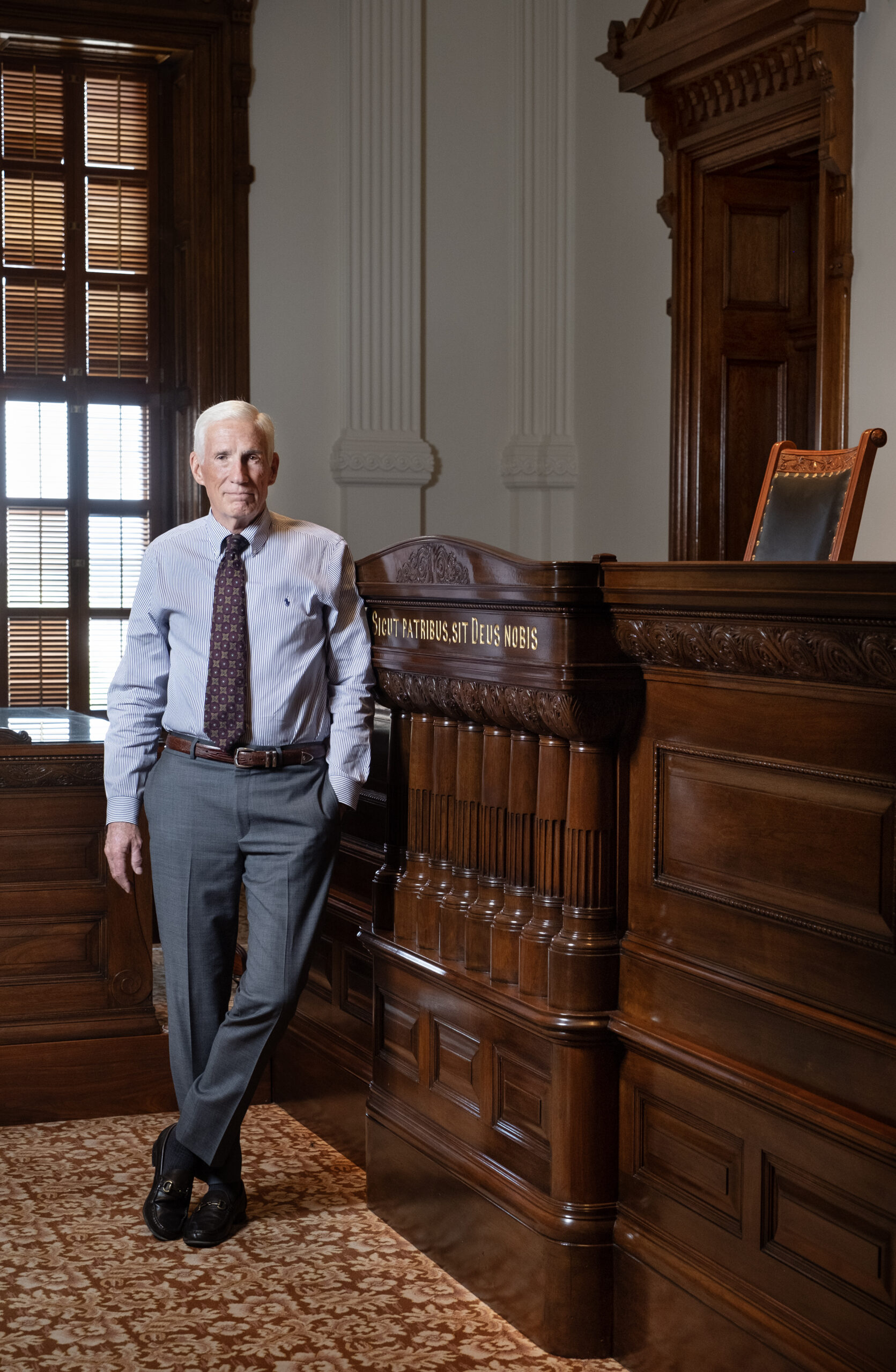

This is a transitional summer for Scott A. Brister, a veteran jurist and lawyer tapped by Gov. Greg Abbott to lead the first new Texas intermediate appellate court launched in 45 years and the only one with statewide jurisdiction.

Brister is finishing briefs and handing off cases to his partners at Hunton Andrews Kurth. He enjoyed a monthlong vacation for the first time in 15 years, traveling with his wife Julie to England, where they attended a C.S. Lewis seminar in Oxford, and to New England.

A well-known figure who has served at all levels of the state judicial system, the 69-year-old appellate specialist is eager to take on the intellectual challenges he will face as chief justice of the Fifteenth Court of Appeals. He’s ready to put his formidable work ethic to the task of deciding appeals involving the state and creating jurisprudence for the fledgling business courts.

The workload, even for an overachiever like Brister, will be immense. An estimated 70 state government-related cases pending in other intermediate appellate courts are lined up for immediate transfer when the court opens for case filings Sept. 1.

The Legislature in 2023 created the new intermediate appellate court to provide a statewide perspective on appeals where the state is a party and to handle cases from the newly created Business Judicial District, a system of trial courts slated to decide certain high-stakes, complex litigation. Abbott has named 10 individuals to serve as business court judges in five urban areas.

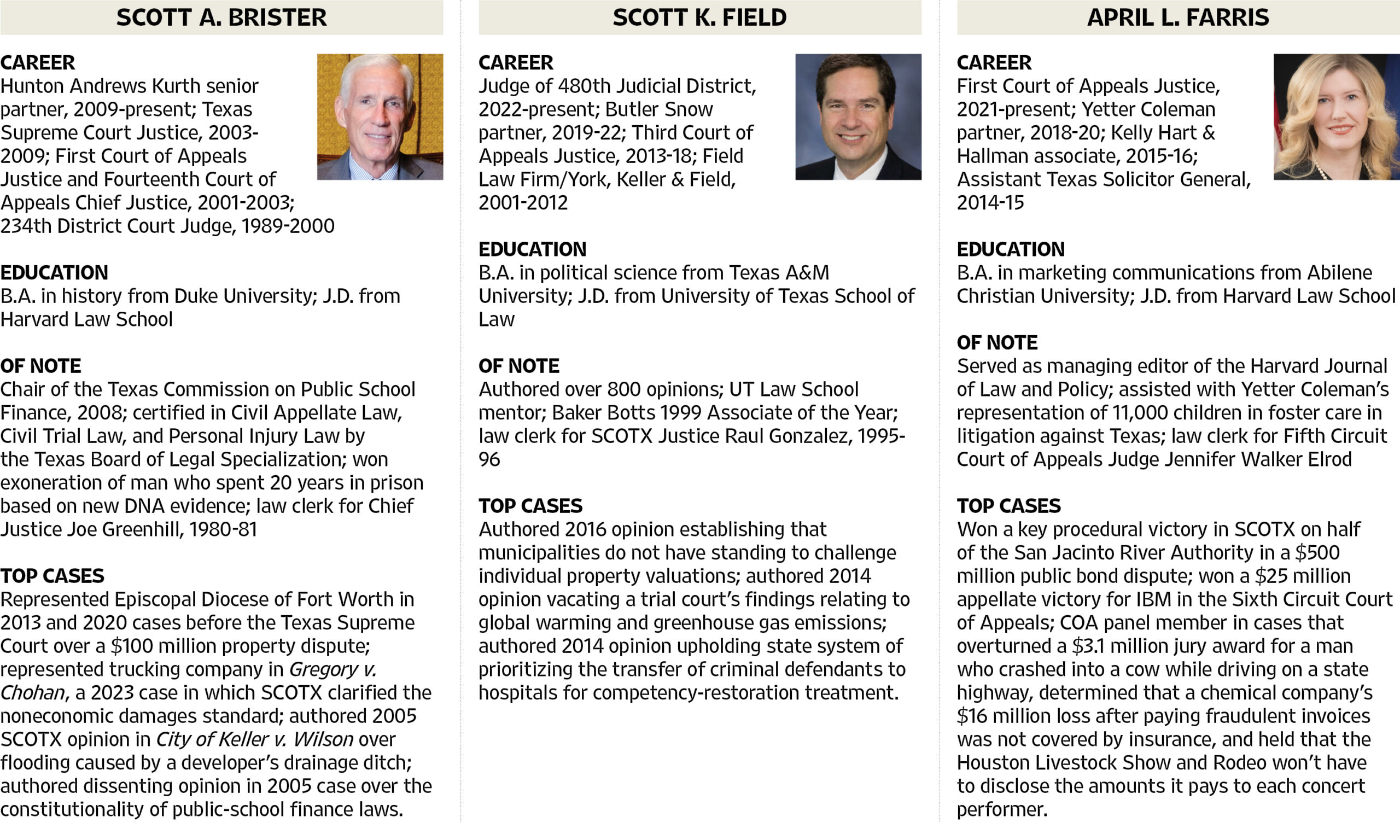

Joining Brister as initial appointees are Scott K. Field of Liberty Hill and April L. Farris of Houston, who also are transitioning from their current judicial roles.

Field is a district court judge in Williamson County and a former justice on the Third Court of Appeals. His six years on the Austin-based court of appeals will be valuable experience in navigating the state-involved cases.

Farris is a justice on the First Court of Appeals who previously was an appellate litigation partner at Yetter Coleman and an assistant Texas solicitor general. Before taking the bench in 2021, she successfully argued cases at the Fifth Circuit, Sixth Circuit, the Supreme Court of Texas and various intermediate appellate courts.

The trio have a combined 30 years of judicial service. All Republicans, they are expected to bring a conservative philosophy to deciding issues involving state laws and regulations. The court currently handling most of those cases, Austin’s Third Court of Appeals, has six elected Democrats.

Brister served six years on the Texas Supreme Court, three years as justice and chief justice of the First and Fourteenth Courts of Appeals, respectively, and 11 years as a district court judge in Harris County.

Thomas R. Phillips, a former Supreme Court chief justice and unofficial historian of the Texas judiciary, said having an experienced set of judges in place will help the court find its footing.

“They’re going to be very busy from the first and, of course, a part of the promise from this whole new scheme is for not only more consistent, but more efficient justice,” said Phillips. “They’ll be faced with an expectation by the bench and bar that they move their matters expeditiously.”

Darlene Byrne, chief justice of the Third COA, said her court is expecting to transfer at least 50 cases, and the other 13 intermediate appellate courts have identified 15 to 20 more. They will involve state officials, executive branch administrative agencies and higher education institutions.

“The bulk of the cases appear to be administrative law-related, but some relate to taxes and elections,” said Byrne.

Some of the appeals center on disputes such as the granting of environmental permits and pollution enforcement orders, while others could challenge the constitutionality of statutes and administrative rules.

One high-profile case likely for transfer is a long-running battle by a group of news organizations seeking public records from the Texas Department of Public Safety regarding the May 2022 mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde. The Office of Attorney General sought and received three extensions to delay their opening brief by three-and-a-half months, putting the state’s appeal on the transfer track.

Work Hard for Less Pay

The potential of debuting an entirely new type of court in a state that already has far more appellate courts than any other is an exciting challenge for Brister.

“How do you put together a staff? How do you put together, you know, what do you do about precedent? What do you do about the jurisdictional uncertainties? So, it’s a new challenge,” Brister said.

“I would not have applied to the Texas Supreme Court to go back there. They’ve got plenty of good people to do that, plenty of good people in the other courts of appeals,” he said. “I’ve been on more courts than probably anybody ever in this state system. And so, I just felt like I could probably contribute to that for a while, at least until I age out of the system.”

Under the state’s mandatory judicial retirement age of 75, Brister believes he could serve through the end of 2030.

While some former colleagues may be shaking their heads at his decision, Brister said most have been supportive.

“I’m a known quantity,” he said. “I’ve written hundreds of opinions and been in the system, met thousands of lawyers.”

He relishes his time on the trial bench in Harris County during the 1990s.

“It was the heyday of litigation with John O’Quinn, Joe Jamail, all the greats. It was a fabulous place to be a judge watching Rusty Hardin, these people, try cases. They were just masters. So, it was a wonderful education.”

Brister accepts losing a significant part of his earnings to go back into public service, even though that lower judicial pay was the reason he resigned from the Supreme Court in 2009. He said the return to private practice was necessary to pay for the higher education of his four daughters.

Now that the youngest is finishing her master’s degree at the University of Edinburgh, it was “serendipity,” he said, that he was at a place in his personal life where he could apply for the court. He was struck by the challenge of creating a new court “from scratch.”

“I wasn’t unhappy where I was. I was certainly making more than I’ll be making next year,” said Brister. “But I loved the work of a judge. I didn’t love the politics or the fundraising and stuff like that. That’s just what you do. But I love the work. I get the feeling of, uh, you can do some level of justice.”

Since leaving the bench, Brister has been involved in numerous high-profile appeals in which he often handled briefing while co-counsel delivered oral arguments.

He was on the winning side of a decades-long fight over $100 million in church property after a split between The Episcopal Church and Episcopal Diocese of Fort Worth. The dispute twice went to the Texas Supreme Court.

In May, Brister was on the legal team that won reversal of a $12 million verdict in a personal injury case because the plaintiffs’ lawyer during closing arguments injected the idea of racial and gender bias as a possible reason that the defendants wanted reduced amounts awarded to a female African American plaintiff.

In another case that turned on an improper jury argument, Gregory v. Chohan, he helped win a new trial on noneconomic damages for a trucking company and driver involved in a fatal crash.

Phillips, who served on the Supreme Court with Brister, said his former colleague brings a breadth of experience unparalleled in the history of Texas.

“A Scott Brister opinion is thoroughly researched, carefully organized and beautifully written,” said Phillips, a partner at Baker Botts. “He does his own work. He’s not one of these judges whose opinion style seems to magically change from one term to the next.”

It’s unclear how soon business court cases will reach the Fifteenth, but there are likely to be early challenges on jurisdictional issues. Brister said he expects the court of appeals over time will develop an expertise on corporate cases involving shareholder suits, securities claims, governance and financial disputes.

“Will that be better for business cases? There are usually businesses on both sides. So, I don’t know whether that’ll be better for a plaintiff or defendant, or you can’t tell,” he said.

Lawyers representing industries regulated by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and other state agencies with regulatory authority are expecting a significant contrast with the Third COA. A half dozen well-known appellate practitioners contacted for this article declined to discuss how they may alter their briefing and arguments for the new court.

Historic Capitol Courtroom Eyed

The Office of Court Administration is working to secure space for the new courts and distribute funding to hire staff. At least one law school, Texas A&M University School of Law in Fort Worth, has expressed interest in housing a business court.

Chambers for Brister, Farris and Field and the clerk’s office will be located in the William P. Clements state building near the Capitol. Brister has suggested the court could hear some oral arguments in the meticulously restored courtroom on the third floor of the Capitol where the Supreme Court met until 1959. While the elevated bench is conveniently set up for three justices, restrictions by the State Preservation Board on use of the historic space, including not bringing pens into the room, could be a hurdle.

Brister is completing several appellate briefs and handing off about a dozen pending appeals, including a high-profile SCOTX case in which Facebook owner Meta Platforms Inc. is opposing the transfer of Jane Doe sex-trafficking cases to an MDL involving similar allegations against Salesforce Inc. Salesforce is accused of selling its software to Backpage.com, a website that was shut down by the U.S. Department of Justice in April 2018.

The case, set for argument Oct. 1, could provide direction on the propriety of a “tag-along” transfer to an existing MDL for the first time since the Supreme Court wrote the rules on multidistrict litigation in 2003.

Brister has a special interest in the case because he helped write those rules. In Meta’s petition for review, Brister said that the Supreme Court has never approved or modified the transfer standards developed by the MDL panel and should finally do so in the Jane Doe cases.

“Our argument is we’re not related enough, and the Supreme Court, I think, will decide that in this case, given some parameters,” he said.

As the only member of the Supreme Court who disagreed with the court’s 2005 ruling that the state’s public school finance system was unconstitutional, the Waco native was drawn back into public service in 2018 when state leaders tapped him to chair a commission that tackled the difficult issue of school funding. The Texas Commission on Public School Finance, a panel of lawmakers and educators that met for one year, made recommendations for a significant investment in low-income and other historically underperforming student groups and the lowering of property tax rates. Those policies were largely adopted in landmark legislation in 2019.

Brister said he wasn’t even following the 2021 legislative debate on the business courts until he was asked late in the session to write an opinion piece for the Austin American-Statesman arguing that the Texas Constitution allows for creating a new statewide appeals court.

In the article, which ran May 12, 2023, Brister wrote that the constitutional requirement that the state “be divided into courts of appeals districts” does not mean they must be completely separated, noting that for nearly 60 years two courts of appeals in Houston have had identical districts.

When Brister was chief justice of the Fourteenth COA and the state was facing a budget crunch, he proposed combining the two Houston appeals courts. The idea did not gain traction with lawmakers but did lead to a combined clerk’s office, which Brister said likely saves about $100,000 in yearly salaries.

A constitutional challenge to the structure of the Fifteenth Court of Appeals emerged in a case brought by Dallas County against the Texas Health and Human Services Commission for allegedly failing to comply with obligations to transfer inmates who have been deemed not competent to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity from the county jail to state hospitals. The challenge is pending before the Texas Supreme Court and could delay cases from being transferred Sept. 1.

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified where Scott Field received his undergraduate degree. It was Texas A&M University, not the University of Texas at Austin. Additionally, he served six years on the Austin-based Third Court of Appeals, not five. The Lawbook regrets the errors.