© 2015 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden

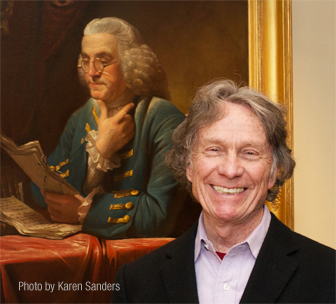

(March 25) – Nine years ago, Forbes estimated the net worth of maverick entrepreneur Sam Wyly at $1.1 billion. His business savvy created tens of thousands of jobs and put billions of dollars into the pockets of investors.

Wyly and his brother, Charles, gave $67 million to charities. They set up trusts in the Isle of Man that would pay them and their family millions of dollars in annual annuities for the rest of their lives. The brothers bought mansions in Dallas and ranches in Aspen.

“Circumstances sure can change fast,” Wyly says.

Today, he is fighting for his family’s fortune and future in U.S. Bankruptcy Court. The $20,377,496 he has in his bank account is frozen. His every expense, including the cable TV bill and insurance for his Subaru, is reviewed and approved by a judge.

During the past five months, Wyly sold his plush New York City apartment for $4 million and his cherished independent bookstore in Aspen for $6.5 million. Next week, the family’s 244-acre Rosemary’s Circle R Ranch near Aspen will be placed on the market for $50 million. In May, auctioneers in Dallas will sell more than 150 pieces of antique furniture and rare artwork, including an original Norman Rockwell portrait of President Richard Nixon.

“We’ve had to live through tough times before and we are doing it now,” he says.

Wyly is under court order to pay the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission $198 million as a penalty for hiding stock trades through offshore trusts. The estate of Charles Wyly, who died in 2011 in a car crash in Aspen, has to surrender another $101 million.

Now, the IRS says it may go after Wyly for as much as $540 million in unpaid taxes.

“It’s a disaster, but it could be worse,” Wyly says. “It was much worse when we lost the state high school football championship. Now that was a long ride home.”

In his first interview since U.S. District Judge Shira Scheindlin of Manhattan issued the record-breaking judgment against the brothers in February, Wyly talked to The Texas Lawbook about his battle with the SEC and IRS, his decision to file for bankruptcy, his $100 million legal fees and his future.

Primarily, he said that he is glad to be back home in Texas.

“We would have won against the SEC if the trial had been in Dallas,” he says. “I went into the trial in New York with an open mind about the judge, but I saw pretty quickly that the judge viewed ‘Texan’ and ‘rich’ as bad words.

“Going from New York to Texas is like going from hell to heaven,” he says.

Wyly founded United Computing Co. in 1963 with only $1,000 in the bank and grew it into a multi-million-dollar computer services company. In 1967, Sam and Charles purchased the Bonanza Steakhouse chain and expanded it to 600 stores before selling it in 1989. In 1982, the Wylys bought the controlling interest in Michael’s, the craft store chain. It grew from a $10 million in revenue private company in 1982 to $1.2 billion public company in 2006.

The SEC originally charged the Wylys with insider trading related to a series of trusts they created in the Isle of Man in the early 1990s. Those trusts are worth about $382 million and pay Wyly about $16 million a year, according to court documents.

Judge Scheindlin rejected the SEC’s insider trading allegations against the Wylys, but the jury found that the trusts were used to hide stock divestitures of publicly traded companies from federal regulators.

“We filed thousands and thousands of financial documents with the IRS and SEC, but the case against us was basically, we should have filed a few more,” he says. “But no one lost any money.”

Wyly says he turned over more than 1.4 million pages in financial documents to the government already, dating back to 1992 when the trusts were established.

“The government spent a massive amount of money on this case,” he says. “It is bad law and bad public policy for the SEC to attack people who create jobs and yet they miss Bernie Madoff and Allen Stanford, two men who caused people to actually lose billions of dollars.

“The SEC is like a monarch,” he says. “It has an unlimited ego.”

At the end of the SEC trial in New York, Wyly was hit with more bad news. The IRS announced that it plans to file a claim in the neighborhood of $540 million against the Wylys for unpaid taxes related to the trusts.

Facing the $198 million penalty to the SEC and a possible $540 million collection effort by the IRS, Wyly filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which is very rare for individuals. Chapter 11 is usually used by businesses seeking to restructure their finances and consolidate or eliminate debt.

But Chapter 11 provided one key weapon for Wyly in his battle with the government: it automatically stayed all collection efforts and prevented the SEC and IRS from attempting to seize his personal assets.

“The alternative was to sit still and let the SEC and the IRS go after our client and his assets in federal court in New York,” says Josiah Daniel, a bankruptcy partner at Vinson & Elkins in Dallas. “It was a simple choice.”

Daniel modeled Wyly’s bankruptcy petition and strategy after another prominent case from 25 years ago. Dallas oilmen Nelson Bunker Hunt and William Herbert Hunt filed for bankruptcy in 1988 after the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the IRS charged the brothers with illegally cornering the silver market in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Facing crippling fines and penalties, the Hunts were able to reach a settlement with the CFTC and IRS through the bankruptcy process.

“We think the Hunt brothers bankruptcy offers the perfect blueprint for us reaching a reasonable agreement with the SEC and IRS,” Daniel says. “The Hunt bankruptcy centralized the process.

“Just as happened in the Hunt brothers case, I believe that there’s a deal to be made in which my client retains a significant amount of assets and yet pays a significant amount to the government,” he says.

U.S. Bankruptcy Chief Judge Barbara Houser is the perfect judge to handle the Wyly case because she was involved in the Hunt brothers bankruptcy, too. Houser represented Minpeco, a Peruvian mineral company that was the second largest creditor in the case against the Hunts.

In addition, Grover Hartt, a Dallas-based lawyer with the U.S. Department of Justice’s tax division, represented the IRS in proceedings against the Hunts in 1988 and he represents the agency now against the Wylys.

Neither Judge Houser nor Hartt would comment, citing their involvement in the ongoing Wyly litigation. A spokeswoman for the SEC said the agency also could not comment.

When Charles Wyly died in 2011, the SEC substituted his estate as a defendant in the securities litigation. Although Dee Wyly, Charles’ wife, is not a defendant in the SEC case, the federal agency had all of her accounts and the accounts of her children frozen under the theory that any money they had was the result of her husband’s allegedly ill-gotten gains.

As a result, Dee Wyly also filed for bankruptcy in Dallas last October. The federal court approved a monthly budget of about $33,000 for Dee Wyly. Half of the $33,000 goes toward maintenance of her Colorado home, which is currently for sale.

“These are not tycoons who made their money raping and pillaging,” says Judith Ross, a lawyer for Ms. Wyly. “Being wealthy is not illegal the last time I checked.

“Dee has done more for charity in Dallas than any person I know,” Ross says. “I swear that I think the SEC’s single mission sometimes is to make this 80-year-old widow as miserable as possible.”

“The issues facing Wyly are very similar to those facing the Hunts,” says Russ Munsch, a shareholder at Munsch Hardt Kopf & Harr who represented Bunker Hunt.

“The issues facing Wyly are very similar to those facing the Hunts,” says Russ Munsch, a shareholder at Munsch Hardt Kopf & Harr who represented Bunker Hunt.

“I agree with Josiah that bankruptcy is the best mechanism for resolving this, but he will have a long and difficult road in negotiating with the IRS and SEC and reaching an agreement with them,” Munsch says.

Lou Strubeck, a bankruptcy partner at Norton Rose Fulbright who also was involved in the Hunt case, says Wyly made the right move in filing for bankruptcy, but he said it will not be an easy dispute to resolve.

“The government is going to be very aggressive and is going to seek to control the bankruptcy process,” Strubeck says.

The parties have met twice to discuss possible settlement terms and more meetings are on the calendar, according to lawyers involved in the matter.

The biggest legal issue in the bankruptcy case is that the IRS still has not said how much Wyly owes in back taxes.

“The IRS audited our taxes every year for more than a decade but still has never made a claim against us and has never asked us for even $1 more than we’ve paid,” Wyly says. “We had to drag the IRS into court because I don’t want this hanging over the heads of my children for years.”

Between 1992 and 2013, Wyly paid $160 million in federal taxes on income he received from the trusts, which essentially converted equity wealth into a fixed annual income stream. Charles Wyly paid $79 million in taxes during that same time period.

“The Wyly family wants to pay any taxes it owes, but it shouldn’t have to pay the taxes twice,” Daniel says.

Judge Houser has given the IRS an April 17 deadline to submit its bill. She has scheduled the trial to take place next January. The government asked to have the trial in the summer of 2016 to allow it enough time to prepare. Wyly’s lawyers and the other creditors wanted to have the trial this summer.

“Every day that this bankruptcy battle goes on, there is less money available for the creditors because the cost of bankruptcy is so high,” says Mark Mullin, a partner at Haynes and Boone and the lead lawyer for the creditors committee in the Wyly bankruptcy case.

Legal fees have been Wyly’s single biggest expense and a drain on his family fortune, Wyly says. He paid the Dallas law firm Bickel & Brewer about $80 million to fight the SEC and then replaced it two years ago before trial with Houston-based Susman Godfrey, which was paid an additional $6.1 million, he says.

Wyly just hired former Stanford Law School Dean Kathleen Sullivan to handle his appeal of the SEC fraud case to the U.S Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Sullivan is charging Wyly $1,175 an hour.

“That is a lot of money, but if Sullivan is successful in getting the $198 million penalty reduced, it puts more money into the pockets of the creditors,” says Mullin.

Legal fees in the bankruptcy case are another $250,000 a month.

For most people, bankruptcy is a shameful symbol of failure. For Sam Wyly, bankruptcy court is a refuge, a sanctuary. He has attended every court hearing. He views Judge Houser as “an honest judge who has been tough but fair.”

Wyly says he doesn’t mind having to cut his spending habits or reduce the size of his estate. To point out that he’s frugal, he says he cancelled his American Express card to eliminate the $450 annual fee. He flies back and forth to Aspen for free using American Airlines “Air Passes” that he purchased more than two decades ago.

“Don’t worry about me,” he says. “I only need one car and one house.”

Wyly bought his house on Beverly Drive across the street from the Dallas County Club in 1965 for $160,000. It is now valued at $12.5 million. Under the Homestead provision in the Texas Constitution, the government cannot seize an individual’s primary residence through bankruptcy court.

Every morning shortly after sunrise, he walks three-quarters of a mile to Starbucks in Highland Park Village, where he enjoys a latte and oatmeal with dried blueberries.

At age 80, Wyly says people should not feel sorry for him. He is putting the final touches on a new book he’s authoring called “The Immigrant Spirit: How Newcomers Enrich America.”

“I have to be an entrepreneur again, he says. “Hell, this is what entrepreneurs do – we work hard.”

© 2015 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.