Federal trade secrets cases filed in Texas 2016-2020

Fifteen years ago, if you found yourself observing trade secrets trials back to back, you’d probably feel a bit like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day as the same fact pattern played out: Employee leaves job for competing company. Employee either did or did not bring their old company’s customer list with them. New company starts selling a competing product to said customers. Litigation ensues.

The “rogue employee” narrative is still predominant in 2021, but now there are many more plot lines companies lay out when they sue to protect their trade secrets. And the plot narratives are far more convoluted than what they used to be.

Legal experts say that rapidly changing technology, the passage of a federal trade secrets law, an increased mobility among workers and the numerous hurdles in pursuing patent infringement claims are all changing the landscape of trade secrets litigation — and are also causing a steady uptick in these kinds of lawsuits both across Texas and nationwide.

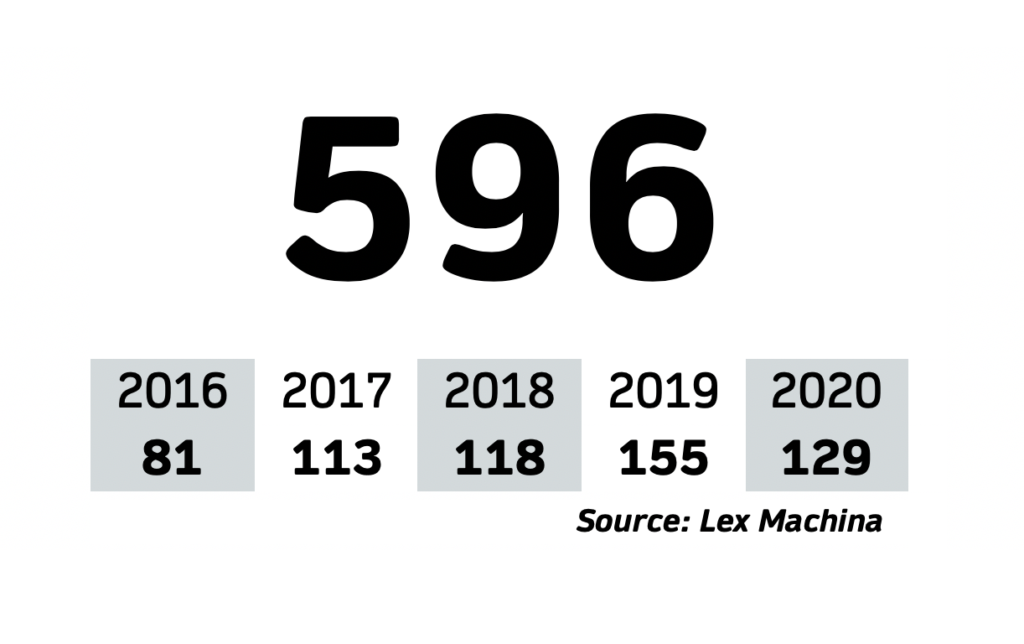

According to a new report by legal analytics firm Lex Machina, federal trade secrets filings hit an all-time high in 2019 after gaining steady growth over the last decade. Federal courts across the nation saw 1,404 trade secrets cased filed in 2019, which was up 20.6% from 2016, the year Congress enacted the federal trade secrets statute. Nationwide filings fell slightly in 2020 to 1,382, but the drop is likely attributed to the Covid-19 pandemic.

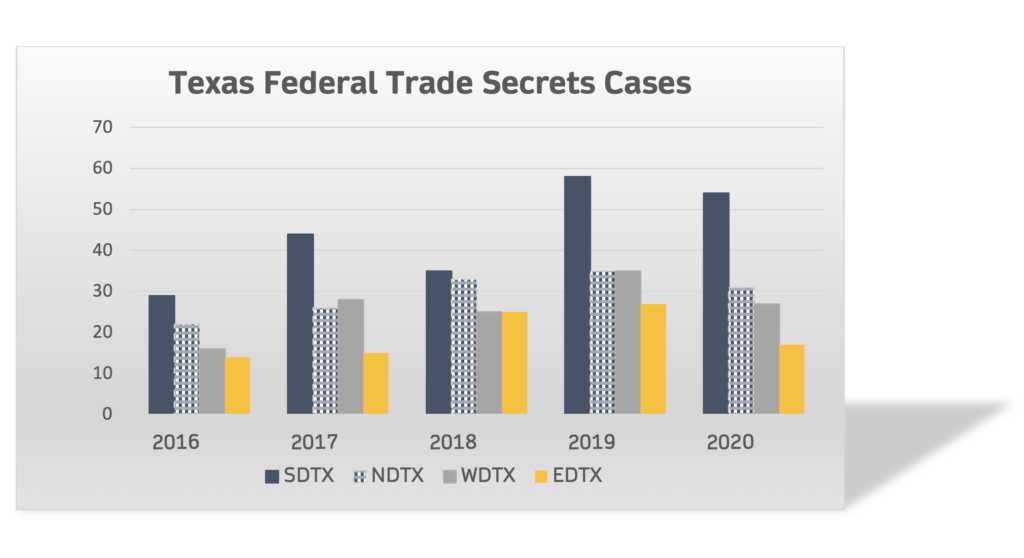

Additional Lex Machina data provided to The Texas Lawbook shows that trade secrets litigation in Texas is growing at an even faster pace. Federal trade secrets cases filed in Texas federal courts in 2020 were up 59% from 2016 — and in 2019, they were up by 91% from 2016.

“Trade secrets litigation is definitely on the rise, said Tim Durst, who left Baker Botts last week to join O’Melveny & Myers’ new Dallas office. “Trade secret cases are motivated by the movement of employees and when business ventures fall apart.”

Texas legal experts think the activity will continue to pick up in both state and federal courts due to layered and nuanced phenomena surrounding modern businesses and legal strategy that’s often advantageous to plaintiffs.

“In the old days, trade secrets were not necessarily tech-driven, so people talked about things like locked cabinets,” said Natalie Arbaugh, a partner at Winston & Strawn. “As we became increasingly digitized, we [now] have hacker issues, cyber concerns … companies do what they can to create encryption and firewalls, [but it’s] harder to control information and easier to walk out the door with information.”

“I think we’re seeing more sophisticated trade secrets cases that are bigger dollar, bigger technology and not just the rogue former employee cases,” said Aimee Fagan, a partner at Sidley Austin. “A lot of times it was because two companies were courting each other in some context [while] evaluating a partnership or an acquisition or working together on some project that required sharing information. Everyone’s using confidentiality agreements and NDA agreements that have very strong language, so what ends up happening is a lot of tools are there to create litigation. I am seeing more and more cases that arise out of M&A transactions.”

As a result, experts say, companies are getting more aggressive about protecting their intellectual property and proprietary information.

“Across industries companies are becoming more aware of the value of their intellectual property and a need to preserve that value,” said Maria Wyckoff Boyce, a partner in Hogan Lovells’ Houston office.

More notable data

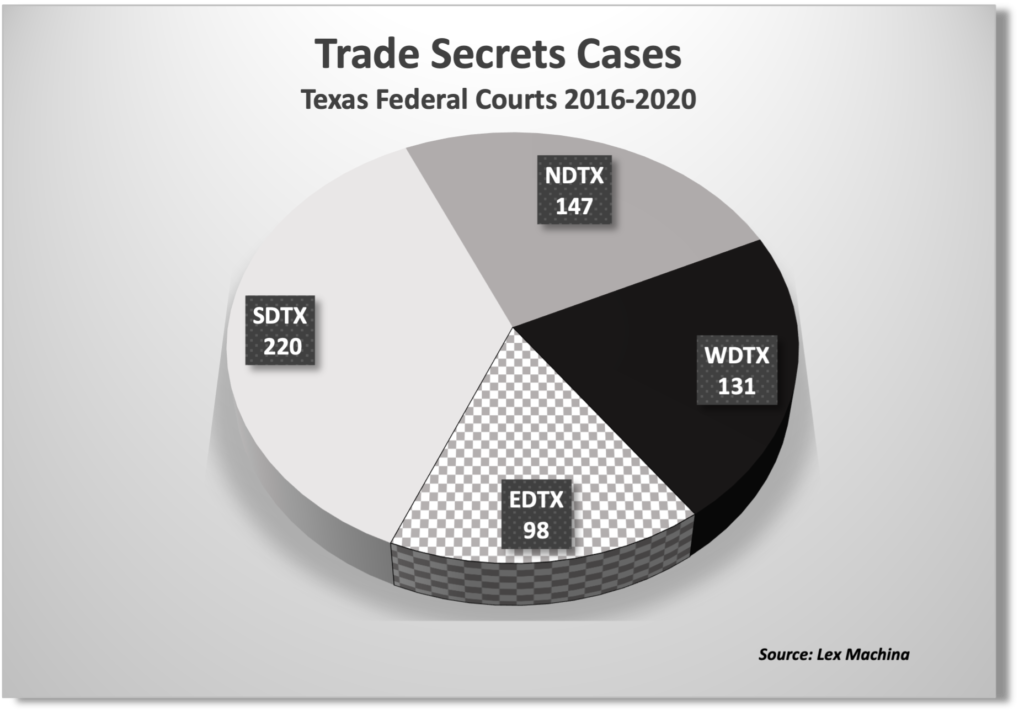

The Lex Machina data shows that the Southern District of Texas has the seventh busiest trade secrets docket in the country, with 220 such cases filed there between 2016 and 2020 — 3.3% of all federal trade secrets cases filed nationwide. Experts say the activity is likely attributed to the diversity of industries in the Houston area and the technology-heavy nature of today’s energy sector. The Central District of California ranked No. 1.

However, a few individual judges in Texas appear to be far busier with these cases than most. Although the Eastern District of Texas had the least amount of trade secrets cases compared to Texas’ other three districts between 2016 and 2020, EDTX’s Judge Amos Mazzant handled the most in the U.S. According to the Lex Machina report, there were 50 trade secrets cases filed in the Sherman-based district judge’s court during this five-year period.

In addition to Mazzant’s reputation for having an expertise in trade secrets cases and his willingness to move cases along quickly, legal experts say the number of large, tech-driven companies headquartered within the Sherman division — which includes Plano — is another factor.

“I think folks overlook that several technology companies have a significant presence in the Eastern District and surrounding counties,” said John Lahad, a partner at Susman Godfrey.

Plus, before mid-2019, when U.S. District Judge Sean Jordan took the bench in Plano, Judge Mazzant had 100% of Sherman’s civil docket, Lahad said.

Looking forward, there’s also large-dollar trade secrets verdicts recently rendered by Sherman juries to consider, experts say. For example, this spring, two separate juries in Judge Mazzant’s court awarded AMS Sensors USA an $86 million trade secrets verdict and Plano-based property management software company ResMan a $152 million verdict (which has since been reduced to $62 million).

“Large verdicts in a handful of trade secrets trials, such as ResMan, fuel the filing of even more cases,” Durst said.

Judge Robert Pitman of the Western District of Texas had the second busiest trade secrets docket in the country from 2016 through 2020, the Lex Machina report shows. There were 46 trade secrets cases filed in Judge Pitman’s court, located in WDTX’s Austin division. WDTX’s Judge Lee Yeakel, also of the Austin division, had the ninth busiest trade secrets docket, with 30 cases filed in his court over the five-year period. The other 10 busiest trade secrets judges were based in the Central District of California, Southern District of Ohio, District of Colorado and District of Delaware.

Other data indicates that Texas federal courts are home to the most adjudicated trade secrets cases. According to a report published last year by global investment bank Stout, which examined trade secrets trends in federal courts between 1990 and mid-2019, 19% of published trade secrets case resolutions were in Texas — 20 in the Eastern District, 11 in the Western District and six in the Southern District.

Multiple sources confirmed that there’s currently no reliable way to tally trade secrets misappropriation claims in Texas state courts because it’s based on keywords.

Early 2010s: good news for trade secrets, bad news for patents

Experts point first to a culmination of changes in intellectual property law over the last decade as the foundation for the growth in trade secrets claims.

Before the codification of any state or federal trade secrets law, litigants in Texas relied primarily on common law while trying to protect their trade secrets in the courtroom. That changed in September 2013, when Texas adopted the Texas Uniform Trade Secrets Act, the Lone Star iteration of a 1979 uniform act that has since been adopted in 48 states.

The TUTSA changed the game for trade secrets disputes in state court, giving companies a clearer, more streamlined path for obtaining injunctive relief and recovering damages — including attorneys’ fees.

In May 2016, federal lawmakers enacted the Defend Trade Secrets Act, which expanded federal courts’ ability to handle trade secrets disputes while providing the same benefits that companies gained in state court after the passage of the UTSA.

While it was still possible to file a trade secrets claim in federal court before Congress enacted the DTSA, you would have to have diversity jurisdiction and the claim would have to go along with another federal cause of action, [such as a] patent infringement claim, Lahad explained.

“With the DTSA, you’ve got a uniform definition of a trade secret and definition for misappropriation,” Lahad said. “The definition of a trade secret under the DTSA is pretty broad.”

Meanwhile, plaintiffs in patent litigation received some bad news from the U.S. Supreme Court in a series of opinions.

Between 2012 and 2014, the nation’s high court handed down its decisions in Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics and Alice Corporation v. CLS Bank International, a trio of opinions that limited what could be patentable in the context of protecting corporate assets. The decisions particularly impacted the healthcare, life sciences and software industries.

These opinions added to a list of drawbacks that all corporate general counsel consider when they’re trying to protect their intellectual property in the form of a patent.

Source: Lex Machina

“You may see some companies maintaining some technological advancements as trade secrets rather than patenting them,” Lahad said. “With patents, of course, you trade disclosure for the right to exclusivity … and patents of course expire. You can have exclusivity but it’s a limited life cycle, whereas trade secrets last forever.”

Strategic advantages to trade secrets cases

To be sure, patent lawsuits are still white-hot in Texas and more abundant in the federal court setting than DTSA claims. The Texas Lawbook reported last week that Texas has reclaimed the throne as the nation’s patent litigation capital. But patent cases are still expensive to litigate and come with a variety of procedural and administrative hurdles, which experts say is leading more companies to consider pursuing trade secrets claims over patent infringement — or, in appropriate circumstances, a hybrid of both claims.

Patent litigation hurdles that plaintiffs likely will face throughout the life of their suit include Markman hearings, defendant counterclaims that challenge patent validity and the interlocutory appeals to the Federal Circuit that may follow. These hurdles draw out the litigation and grow the legal bills for companies.

Trade secrets cases, on the other hand, offer fewer affirmative defenses for defendants and often provide an easier route to trial, Boyce said.

“It’s my opinion that trade secrets cases can be a more straightforward path to trial,” Boyce said. “I believe that for the most part it is easier for a jury to understand a trade secrets case. You’re looking at what is a trade secret, was it protected by the holder of the trade secret and was it taken. You’re not having to get into some of the technical details that you are required to get into to prove a patent infringement case.”

Part of the complexity of a patent infringement trial is the heavy reliance on expert witnesses by both sides in helping them prove their case — which may or may not keep a jury engaged. Trade secrets, on the other hand, can be a bit sexier when it comes to captivating the minds of jurors, experts say.

“Juries love conspiracy stories of stolen secrets; it’s a storyline that everybody understands,” Fagan said. “[In] trending media reports, there are allegations of foreign governments [and] companies stealing U.S. intellectual property, so it’s at the top of people’s minds. They believe it happens, and it almost reads like a good spy novel.

“People are aware that their data and their information can be stolen, so I think that’s a sensitive touchpoint now in the U.S.,” Fagan added. “People are keenly focused on maintaining what is theirs.”

Fagan, who also tries patent infringement cases, said trade secrets cases can also provide advantages over patent cases in the post-judgment context.

“The chances of getting a home run in terms of damages [in a patent case] and keeping it seems to be quite diminished,” she said. “There are so many hoops you have to get through in a patent case and if you get a big judgment and it goes to the Federal Circuit, it will most likely get kicked back down. A lot of investment goes into a patent case before a payout is likely. I think trade secrets cases are different. First off, you have more flexibility in where you file, so you get to really think about where to file it, what the appellate court is going to be.”

Trade secrets cases also offer “a real possibility of exemplary damages and a much greater ability to obtain an injunction,” Fagan said, which is “difficult to get in patent cases.”

And when a settlement is the plaintiff’s objective, trade secrets cases can also add advantages, Fagan added.

“[The plaintiff] can assert a laundry list of trade secrets and engage with the defendant in battles on numerous fronts … which makes it easier to survive to a jury trial and likely settle and make a sizable amount of money without going to a jury trial,” she said. “The plaintiff’s attorney often has the opportunity to conform the trade secrets claims to the evidence they later obtain.”

Experts said companies that also have patented intellectual property can choose to pursue both trade secrets and patent infringement claims, but the answer is not always clear.

“I think more and more people are taking a hard look at whether they want to pursue both,” Boyce said. “You could have a really good trade secrets case that has slowed down if you also assert patent infringement. I think companies are giving a really hard thought as to whether [they] should pursue both causes of action and should they perhaps focus on a trade secrets misappropriation claim.

“I think it’s an important question for a company that is contemplating litigation to ask,” Boyce added. “I don’t think the answer is perhaps as obvious as it used to be before trade secrets law became codified and before so many administrative hurdles were created in patent cases.”

Employee mobility and the digital world

Although the ‘rogue employee’ storyline is not the only factor driving trade secrets litigation these days, employment-related events still appear to be the primary catalyst.

According to Lex Machina’s trade secrets report, Littler Mendelson and Ogletree Deakins — two labor and employment firms — ranked first and second, respectively, for filing the most trade secrets cases in federal courts between 2016 and 2020. On the other side of the “v,” Ogletree defended the most trade secrets cases over the five-year period, Jackson Lewis — another employment-focused firm — handled the second most and Littler handled the third most.

Experts say the combination of increased employee mobility and changing technology contributes to the uptick in trade secrets litigation.

“Anybody at the forefront of technological advances is going to be developing and using trade secrets, and they’re more likely to be involved in trade secrets litigation,” Fagan said. “We have the internet of things … there are very few industries that aren’t using technology that is rapidly evolving.”

Experts say both the overall improving economy over the last several years and the Covid-19 pandemic have contributed to employment mobility.

“An economy heating up leads to more employment mobility, more opportunities for trade secret theft and more instances of companies looking to protect trade secrets, which means companies have the resources to fight about it,” said Todd Mensing, a partner at Ahmad, Zavitsanos, Anaipakos Alavi & Mensing.

“You have companies laying off employees from the impacts in business, and you have companies thriving and taking employees,” Arbaugh said. “That mobility — especially when employees leave in groups — is quintessential to trade secrets cases [because] they take information with them. The professional services industry, in particular, is an area where you see lots of movement and trade secrets litigation as the result of Covid.

Tips for companies facing trade secrets litigation from both sides of the “v”

Although trade secrets disputes are unavoidable in this day, experts say there still are proactive measures companies can take to protect their confidential information and themselves if they are subject to a lawsuit.

“Companies cannot train their employees enough to ensure information is treated in the best way possible,” Arbaugh said. “It’s important that employees at every level are treating information as confidential. Sometimes it is that disconnect that causes employees to think they can just leave with information. They signed a confidentiality agreement four years ago and never get reminded of their obligation and think, ‘Oh, I’m just going to take this with me.’”

If you find yourself becoming a defendant to a trade secrets dispute, Arbaugh said, conduct “an investigation promptly, figure out what happened and mitigate as much as possible.

“The answer isn’t always fighting all the way through court,” she said.

For companies doing deals with each other and exchanging confidential information, “there’s going to be some degree of risk no matter what,” Fagan said, but there are still steps that can be taken to try to reduce that risk.

“It would be really helpful to itemize what is being shared and what is actually a trade secret or not,” Fagan said. “Try memorializing what you’re getting that’s really confidential or a trade secret because it can be helpful to mitigate risk.”