© 2013 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

(May 14) – Bankruptcy filings by Texas businesses continue to decline, but legal experts say the trend is a false barometer of economic health and that it is having a negative financial impact on Texas law firms with significant bankruptcy practices.

Some of those legal insiders predict there’s a potential tidal wave of new corporate bankruptcy cases headed this way in 2014 and 2015.

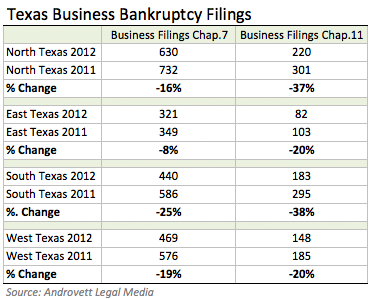

The number of Texas-based companies that filed to reorganize, restructure or liquidate dropped 20 percent in 2012 from a year earlier. The decline continued during the first quarter of 2013, dropping another 11 percent from a year earlier.

The largest plunge came among Texas businesses filing for bankruptcy protection to restructure and reorganize under Chapter 11. During the past 15 months, there were 39 percent fewer such filings in the Northern District of Texas, which includes Dallas, and 41 percent less in the Southern District of Texas, which includes Houston, according to Androvett Legal Media, which tracks such statistics.

Legal experts say the improving economy is a contributing factor, but they almost universally agree that unparalleled low interest rates and a continued stingy credit market deserve most of the acclaim, or blame, depending on the viewpoint.

“The declines in business bankruptcy case filings in Texas – and across the nation – are historic and almost certainly are the product of the highly unusual economic times and monetary policy that has driven interest rates to near zero level on higher quality debt, and to historically low rates on lower quality debt,” says Josiah Daniel, a partner in the Dallas office of Vinson & Elkins.

Hundreds of Texas businesses would have benefited from the protections of Chapter 11 protections from reorganization and restructuring, but Federal Reserve policy has significantly impeded those avenues, according to lawyers.

John Brannon, a bankruptcy partner at Thompson & Knight, says we are “in the era of extend and pretend.”

“It takes a lot of money to go through a true Chapter 11 reorganization,” says Brannon. “If you don’t have the money or don’t have access to the financing, then a Chapter 11 quickly becomes a Chapter 7 liquidation.”

Because money is so cheap, banks are not being pressured to charge off their loans, says Jeff Erler, a bankruptcy partner at Gruber Hurst Johansen Hail Shank in Dallas.

“In turn, the financial institutions allow companies to limp along hoping something in the market will change,” he says. “In the end, I don’t care if you are reorganizing or liquidating, if the credit markets are frozen and there’s no money out there, you are better off turning off the lights, locking the doors and going home.”

The era of “extend and pretend” will eventually have to come to an end, according to Erler and others.

Lou Strubeck, a bankruptcy partner at Fulbright & Jaworski, says that if interest rates increase in any meaningful way, “a number of companies, in a variety of industries, will no longer have access to cheap capital and will be unable to service their debts.

“There are billions of dollars of debt maturing in the next 18 months and at least some ‘experts’ believe that the lenders will not be willing to extend maturity dates as they have in the past,” says Strubeck. “If that is true, there should be a sharp increase in the number of Chapter 11 filings, not just in Texas, but nationwide.”

Strubeck says he is “skeptical that the lenders’ practices will change” during the next year or so, as financial institutions allow maturing loans to be restructured and “kicked down the road.”

“So long as the debt and capital markets have available liquidity and an appetite for distress and restructuring investments, even financially distressed firms may be able to postpone reorganization by more formal processes such as Chapter 11,” says V&E ’s Bill Wallander. “Given that we are in a spot we have never been, it cannot be predicted with certainty when the imbalance adjustment will occur, but our experience is that it will, and perhaps with some persistence.”

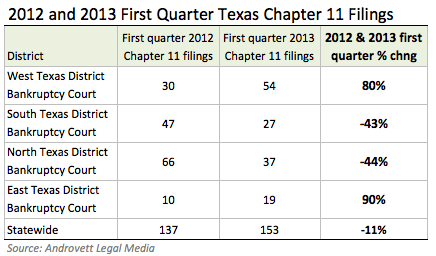

The bankruptcy statistics for the first quarter of 2013, which are tracked by Androvett Legal Media, show an interesting anomaly. The Eastern and Western federal districts in the state witnessed dramatic increases in business bankruptcy filings.

New business bankruptcy filings for the Western District, which includes Austin and San Antonio, shot up 80 percent during the first three months of this year compared to one year ago. Lawyers said that there was no apparent reason for the significant increase, as the businesses were a mixture of small energy companies, restaurants, a couple golf courses and the usual technology start-ups.

The Eastern District, which includes Plano, Tyler and Texarkana, witnessed a 90 percent jump, but lawyers note that the statistical sampling (19 business bankruptcy filings in Q1 2013 compared to 10 a year ago) is too small to make an analysis.

Meanwhile, the past two years have been lean times for bankruptcy practitioners.

“Many Texas law firms beefed up their bankruptcy staffs in 2008 and 2009, predicting there would be a tsunami of Chapter 11s,” says Erler.

The wave was large but brief, he says. The companies that were already on the brink of failure or had cash on hand to conduct a restructuring did so.

By 2011, those new filings were drying up. Law firms redeployed those lawyers into other forms of transactional law practices, including mergers and acquisitions. Other firms have significantly reduced their lawyer count by forcing partners out through compensation reductions or have found other means to push them out the door.

“This is a notoriously cyclical practice and eventually there will be more opportunities for bankruptcy professionals,” says Strubeck. “The questions are when and whether we will see a return to the same levels of activity we saw three or four years ago. The last cycle, while intense, lasted for a relatively short period and was not the kind of sustained increase in work that many bankruptcy professionals expected, or at least hoped for.”

Making matters worse, according to legal experts, is that the larger, more complex corporate bankruptcies are being filed in the Southern District of New York or in Delaware instead of in Texas. That happened with American Airlines, Dynegy, Dallas Stars, Hostess and Super Media.

The reasons vary from Texas bankruptcy judges not being as debtor-friendly as their New York colleagues to the judges in the Southern District of New York simply having more experience. Unsaid, at least publicly, is that bankruptcy judges in New York are more likely to approve higher hourly legal and financial consulting fees than their Texas counterparts.

All eyes are on Energy Future Holdings, which has Dallas as its principal place of business and primary operations, to see if it continues that trend.

“There are fewer bankruptcy filings in Houston because bankruptcy lawyers in New York are saying that the bankruptcy judges here are toxic,” says Hugh Ray, a principle at McKool Smith in Houston. “They say judges in Houston are not as predictable as those in New York, even though they have no proof to support this.

“To most lawyers in Manhattan, when you get beyond the Hudson River, you are camping out,” he says.

© 2013 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.

If you see any inaccuracy in any article in The Texas Lawbook, please contact us. Our goal is content that is 100% true and accurate. Thank you.