As oral argument in a case at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit wound down last month, Chief Judge Carl Stewart had one simple inquiry for the litigator at the podium.

“Chief Judge Stewart, that is a good question,” the lawyer started to answer.

“I know,” the judge responded. “That’s why I asked it.”

Chief Judge Stewart’s seven-year term as leader of the New Orleans-based Fifth Circuit, which handles all civil litigation and criminal appeals from federal courts in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi, expires at the end of September.

On Oct. 1, Judge Priscilla Owen, a former Texas Supreme Court justice who was appointed to the federal appeals court in 2005 by President George W. Bush, will become the circuit’s new chief judge. Judge Jennifer Elrod is expected to succeed Judge Owens.

A 1994 appointee of President Bill Clinton, Chief Judge Stewart was the only African-American on the Fifth Circuit for 17 years. In 2012, he became the first black chief judge in the history of the Fifth Circuit.

“It has been a full and very interesting seven years,” Chief Judge Stewart told The Texas Lawbook in an exclusive interview this week. “There have been some stressful times and matters, but it has been an honor to do this job.”

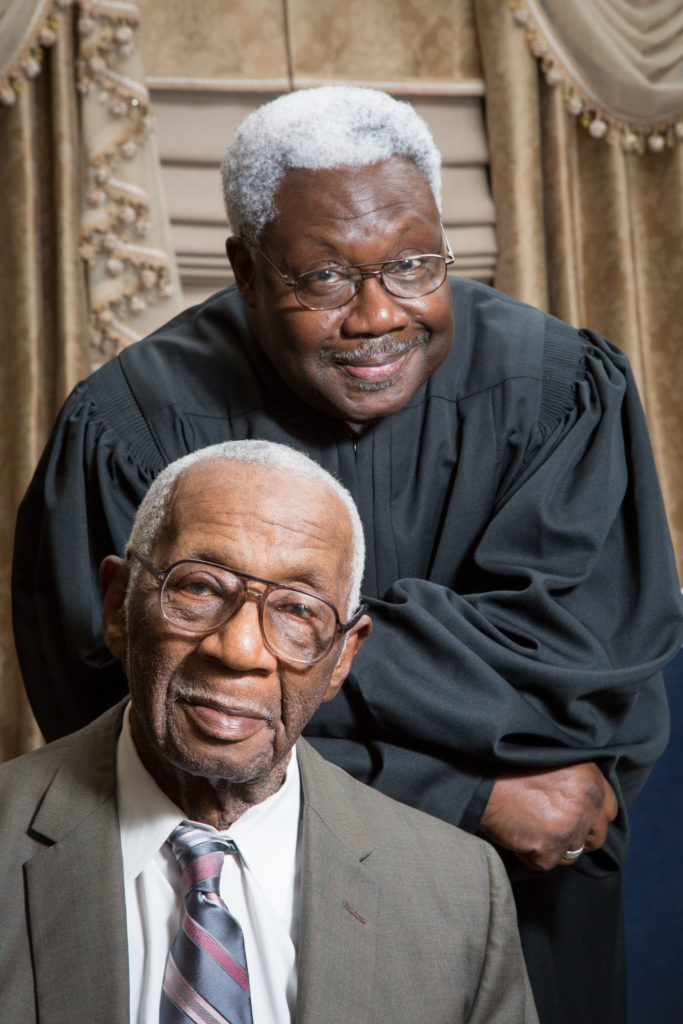

– Courtesy of Stewart Family

During his term, the appeals court has had to deal with some of the biggest legal disputes of the day – abortion, affirmative action, capital punishment, immigration employee/employer rights and healthcare. He also faced significant administrative challenges, including the impact of Hurricane Harvey on the judiciary, two government shutdowns, ever-tightening financial restraints and the integration of six new appointees – five during the past year alone.

“It’s actually been a lot smoother than people might think,” he said. “The new judges have been great to work with and they fit right in. They are extraordinarily smart and talented.”

While Chief Judge Stewart’s congressionally established seven-year term as chief judge expires Oct. 1, he has no plans to step away from the bench or even slow down.

“I do not plan to take senior status anytime soon,” he said. “I was able – even though it was a challenge – to keep hearing cases while taking on the additional administrative duties of being the chief judge. I did not cut back on my case hearing schedule.”

Appointed to the U.S. Judicial Conference’s executive committee by Chief Justice John Roberts in 2017, Chief Judge Stewart said he will not miss all the travel required by the position.

“I’ve had more than my fair share of delayed and cancelled flights, and I’ve had to spend nights in airports more than a few times,” he said.

In the days following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and tightened security at airports, TSA agents asked him for a government ID.

“I showed them my official federal judicial identification, but they said they could not accept that because it did not have an expiration date,” Chief Judge Stewart said. “I tried to tell them there was no expiration date because federal judges serve for life, but I finally just gave them my driver’s license.”

Legacy of Justice

Judges who have served beside him and lawyers who argued before him say Chief Judge Stewart, who is 69, already has a tremendous legacy – a total of 25 years on the Fifth Circuit – that goes well beyond the racial barriers he has busted.

“I have not seen or served under a better chief judge than Carl,” Judge Patrick Higginbotham, who was appointed to the Fifth Circuit in 1982 by President Ronald Reagan, told The Texas Lawbook. “Carl is a great lawyer and judge and leader, but he’s also a truly good person who has strong principles.

“The court has been very lucky to have him as our leader for the past seven years,” Judge Higginbotham said.

In fact, the entire federal judiciary will honor Chief Judge Stewart on Oct. 17 with the 2019 Edward J. Devitt Distinguished Service to Justice Award in a ceremony at the U.S. Supreme Court.

The committee, which was chaired by retired Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, said Chief Judge Stewart’s career “demonstrated his commitment to decency, civility, fairness and justice.”

Lawyers and advocates say that Chief Judge Stewart is known for the evenhanded manner in which he does his job and the way he keeps an open mind to all sides of an issue.

“In my own experience, the chief always demonstrated utmost respect and kindness to lawyers at the podium,” Judge James Ho, a former appellate lawyer who argued multiple cases before Chief Judge Stewart and now serves with him on the Fifth Circuit, told The Texas Lawbook on Wednesday.

“He may ultimately agree or disagree with you, but you could be absolutely certain he would hear you out,” Judge Ho said. “For any advocate, that is exactly who you want — a judge who will listen to a good, well-crafted argument.”

Other lawyers agree.

“Chief Judge Stewart is the epitome of a fair jurist who takes each case on its own merits,” said Baker Botts appellate law partner Aaron Streett. “Like all judges, he has a judicial philosophy that guides him on some of the more controversial cases the court hears, such as those dealing with unenumerated rights or hotly contested en banc proceedings.

“But on the vast majority of cases – the daily bread of a federal appellate judge – Judge Stewart’s approach is defined by a pragmatic and searching analysis of the facts and the law,” Streett said.

– Photo by Kathy Anderson

Advocates point out that Chief Judge Stewart usually welcomes lawyers to oral arguments and he often compliments them at the end of the presentations.

“Despite his friendly demeanor, the advocate is well-advised to answer his questions directly, rather than attempt to avoid them,” Streett said.

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher partner Allyson Ho, an appellate law expert who is married to Judge Ho, said Chief Judge Stewart is “a true judge’s judge.”

“He’s the epitome of collegiality and consensus-building in the mode of the Chief Justice of the United States, John Roberts,” Ho said. “His legacy of character and kindness will be as important and enduring as the cases he decided.”

A Humble Life, Challenges

The son of a World War II veteran and career postal carrier, Carl Stewart was three years old when his parents bought their first home at a newly developed residential area in Shreveport.

Leaders of an all-white church down the street from the Stewart’s new house didn’t want African-American neighbors, and they sought to have building permits reversed and access to water and electricity denied. They even convinced the local sheriff and fire chief to state that they would not service the neighborhood, which led insurance companies to balk at providing coverage.

“We were so excited about our new home and then, all of a sudden, it didn’t happen,” Richard Stewart, the chief judge’s older brother and a former associate general counsel at Verizon told The Texas Lawbook in a 2014 interview. “It devastated our parents. They tried to shelter us, but we knew.

“We grew up in some terrible times,” Richard Stewart said. “We rode in the back of the bus and not by choice. There were stores that wouldn’t let us try on clothes. Our parents told us we would face a lot of obstacles – the color of our skin being one of them – but that we should not let the obstacles dictate our conduct.”

The Stewarts’ youngest brother, James, is now the district attorney of Caddo Parish, which includes Shreveport where that all-white church still operates. Multiple attempts by The Texas Lawbook to contact leaders of the church were unsuccessful.

Judge Catherina Haynes, who serves on the 5th Circuit with Chief Judge Stewart, told The Texas Lawbook in 2014 that “whatever the Stewart parents were doing in raising their children should be bottled.”

“Carl’s brilliant legal mind is housed in a very nice, regular person. I’ve never seen any display of arrogance,” Judge Haynes said.

A graduate of Loyola University College of Law, a young Carl Stewart worked as an Allstate insurance claims agent to pay for his education.

“People involved in accidents would call and I would take their reports,” he says. “Nearly every night, one or more callers would use the N-word and tell me that all those people were liars.”

Chief Judge Stewart said the experiences were hurtful, but he never challenged the callers.

“I have a lot more to be thankful for than I have to be bitter about,” the judge told the ABA Journal in an interview five years ago. “I simply don’t want to waste my time on revenge. Be kind to others, even when they are not kind to you, and you never know whose life you will change.”

– Courtesy of Stewart Family

After law school, he served as a captain in the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s Corps (he served as a defense lawyer for soldiers at Fort Sam Houston) and then a state and federal prosecutor.

Stewart entered the 1985 election for a seat on the Louisiana state trial court. His opponent was a white lawyer who was so convinced the parish would never elect a black judge that he went on a week-long fishing trip the week of the election. When he returned, he learned he had lost to Stewart.

25 Years on the Fifth Circuit

Much has changed during the 25 years Carl Stewart has been on the Fifth Circuit.

“Technology has brought us the most fantastic advances,” he said. “We are no longer a paper document driven court. No longer do we have to lug around huge files of briefs to read on airplanes or at hotels or home. Now, the documents are all on our laptops or pads. Instead of individual faxes, we get emergency documents simultaneously.

“Technology has not only lightened the burden, it has helped the judges be more thoughtful and substantive by allowing us to be able to read the actual record in a case more thoroughly,” he said.

At the end of the day, Chief Judge Stewart said, his favorite part of the job is working with his young law clerks.

In the 2014 interview with The Texas Lawbook, Chief Judge Stewart said he decided as a teenager to become an attorney because lawyers “made a difference in the community.”

Those who know the chief judge best say that is still his primary goal. “Carl believes in doing the right thing,” Judge Higginbotham said. “He has no ego. He understands the role of being a judge better than anyone.”