For Jas Sethi, March 13, 2022 started out as a typical Sunday in the life of a law student.

At the time a second-year student at Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law, Sethi had slept in after a night out with friends. Craving cinnamon rolls, he ordered delivery on Uber Eats from a restaurant with the self-proclaimed “best cinnamon rolls in Chicago.” From his bedroom, he answered a call from his mother.

On the line, he learned about the suicide of his younger sister, 19-year-old Simran Sethi, who had been battling depression and addiction while living in a sober living facility in Georgia. Throughout Simran’s struggle, Jas and his parents had searched in vain for treatment options, only to encounter a shocking lack of providers and protocols with proven success at treating adolescent addiction and depression.

“Everything just fell apart. I think I was probably screaming, I was probably hitting stuff,” Sethi, now a first-year corporate transactional associate at Vinson & Elkins, told The Texas Lawbook. “The first two months it was just, get out of bed, put one foot in front of the other,” Sethi said of the immediate period following Simran’s death. “It was a vague idea in my head that I would want to do something.”

That vague idea will materialize into a concrete action this fall when the University of Texas selects the first recipient of the Simran Sethi Memorial Scholarship in Social Work. The $200,000 endowment that Sethi and UT launched late last year is designed to support graduate students pursuing social work careers that specialize in substance misuse and recovery.

“This gift … advances our school’s mission by providing resources for students who want to work with persons, families, and communities affected by substance misuse and behavioral health challenges,” said Allan Cole, dean of UT’s Steve Hicks School of Social Work. “We are most grateful for Jas’ vision, generosity, and support, all of which will make a lasting difference on many lives.”

Experts say social work is a critical element of substance abuse treatment because, in addition to the clinical side of the field, there is also an administration and policy side of the profession that can influence meaningful reforms to how treatment is approached.

One such expert is Kasey Claborn, a research scientist and clinical psychologist who teaches at the Steve Hicks school, runs the school’s Addiction Research Institute and devotes her career to improving the system of addiction care through implementation science. She said addiction treatment is most effective when social workers are part of the team of care providers because they bring a broader perspective than those who come from a medical or psychology background since they are typically trained to focus on the micro level — individual patient care.

“Social workers have a uniquely trained eye to see the work differently,” Claborn said.

In addition to also being trained at a micro level, Claborn said, social workers can view treatment at a macro level — what kinds of larger system and structural changes are needed — and a mezzo level, which involves the development and implementation of services within a community (school districts, businesses, neighborhoods, city districts, etc.).

“Social workers are great networkers in the community and are very strong in advocacy and coalition building, and all of that is critical for creating change at the policy level from a systems perspective,” Claborn said. “I think social workers should be the conveners within our society for creating that change because they have more training in that and advocacy efforts, and are also better at connecting, whereas the medical [and psychology] field[s] are not really trained in that.”

The new scholarship is the end product of Same Road, a nonprofit Sethi launched in late 2022 in honor of his sister. As he raised funds and learned more through that endeavor, Sethi decided to pivot his efforts in hopes of making more meaningful change in the world of substance abuse treatment.

“The idea in my head was what St. Jude’s is to pediatric cancer I want there to be that for substance use,” Sethi said. “But even at that stage, I didn’t know anything. There is genuine regulatory, political, legal change that needs to happen, and you can’t do that with a nonprofit. So, I put all the money [I raised] from the nonprofit into the scholarship, closed the nonprofit, and now the goal is more policy stuff.”

“I want to make it so that nobody ever has to feel like Simran did,” Sethi said. “I can’t do that all in one day, and I don’t know if I can do that at all, but the scholarship is what I can do now.”

* * *

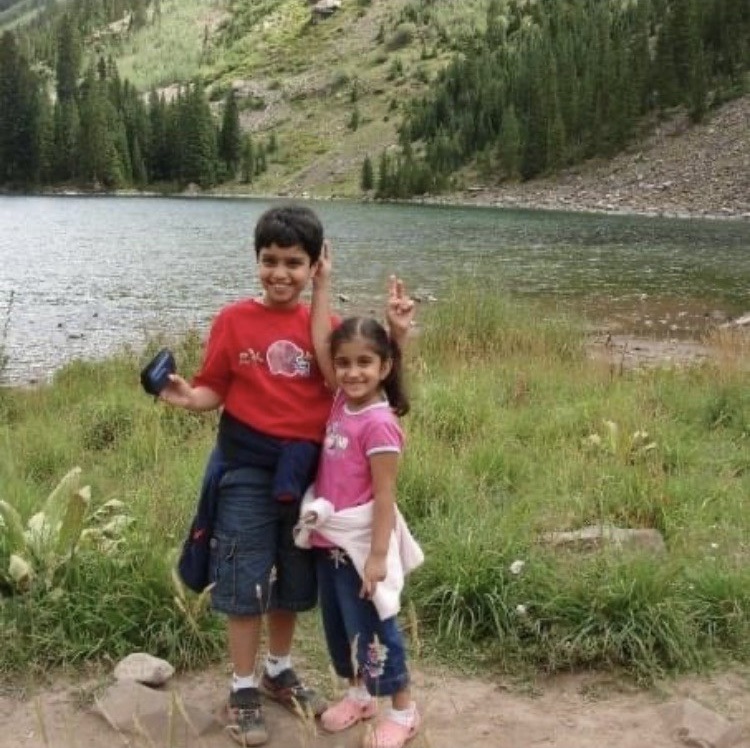

Sethi described Simran as “really artistic” and a lover of music and animals. At the time Simran died, the Sethi family had Happy the Lab, Princess the Pug and another dog named Zara. She also had a chameleon named Karma, Sethi said.

While Sethi and his sister weren’t very close growing up, he said that changed after he went off to college.

“We were really close the last couple of years,” Sethi said. “We would talk every day on the phone for a decent amount of time that I could have been studying. She was genuinely my favorite person on the planet.”

Sethi said his sister’s mental health started getting worse after she started college at Texas A&M University in 2020 during the height of the pandemic, when students were attending class virtually.

“The only people she was interacting with at that stage were her roommates,” Sethi said. “I think it just wasn’t a great situation, and at that point, she started drinking and she started smoking weed. At one point her apartment got reported and she ended up spending the night in jail.”

After Sethi’s parents received a letter that revealed Simran had been arrested, they moved her back home to Frisco, where she continued taking classes virtually.

“The thought process with most people is it’s only, ‘Just say no,’ because that’s what my generation was raised on, that’s what their generation was raised on, and that’s what everybody hears,” Sethi said. “So, their thought process was, ‘We have to remove her from the situation now.’ [But] her use and her drinking just got worse at home. Being in that virtual setting at A&M was isolating, but moving back home was even worse.”

In Frisco, Simran began going to therapy and outpatient treatment, and with those steps in place, Jas and his parents “expected it would sort itself out,” he said, so when it didn’t, “we kind of freaked out.”

The family eventually sent Simran to an inpatient treatment facility in Georgia. Sethi said his sister “did alright” there, but once she was transferred to a sober living facility after completing inpatient treatment, “she was struggling a lot.”

“The thing in the U.S. is almost all treatment for addiction is abstinence only, which is just scientifically not the most effective way to treat substance use,” Sethi said. “It did work while she was there in this controlled setting [and] controlled environment, where every meal is at this time and there’s no outside interaction.”

But once Simran moved to the sober living facility, Sethi said, “there was no structure” beyond regular therapy, group sessions or Alcoholics Anonymous meetings.

“It was basically just an apartment complex [where] you go … and you’re supposed to stay clean,” he said. “And that’s pretty much it.”

Moreover, Sethi said, there was no “day-to-day checking in” beyond Simran having a roommate also in recovery, which he guessed was intended to serve as an accountability system.

“It’s not like you were paired with someone who shared your experience, he said. “There’s absolutely no judgment here, but it would be somebody with a lifelong heroin problem with a college student who has a weed problem. It’s completely different and they can’t help each other, really. They might be able to but it’s not … the way it’s going to work.”

At the time of Simran’s death, it was one of the longest stretches that Sethi had gone without talking to his sister because “I had been really wrapped up in my own stuff,” he said.

“I know you’re not supposed to do this kind of thing, but what if we had talked in those last two weeks?” Sethi wrote in a Facebook post addressed to his sister on the one-year anniversary of her death. “What if I had taken that break from school and come to stay near you when I knew you were struggling? What if I was there for you when I should have been?”

* * *

When Simran died, Sethi said he lost his purpose for attending law school.

“The reason I went to law school was I wanted to make sure that nobody in my family would have to worry about money again,” Sethi said. “And in particular … I wanted to make sure that I could take care of [Simran].”

For every day and every class in the couple of weeks following his sister’s death, Sethi said he would “show up … listen to the lecture for five minutes and then have a panic attack and walk out.”

Eventually he said his professors told him to “do what you need to do, you don’t need to come to class,” and he spent the next month or two “trying to take care of myself” while he got through the rest of the school year.

That summer, Sethi returned to Texas to work in V&E’s Austin office. Being closer to family and living with a group of his closest friends, Sethi said he “had a better support system” and started realizing “there was something wrong in the treatment.”

“There’s something that needs to be done,” Sethi said. “I don’t know what it is, I don’t know how to do it, but …. that’s kind of where I started working on stuff.”

The following year, during the spring semester of Sethi’s third year at Northwestern Law, he was taking a comparative law course called International Team Projects that involved a trip to Portugal where Sethi’s group studied that country’s approach to drug decriminalization and substance use treatment in comparison to the U.S. It was there where he learned about the “harm reduction” approach to addiction — which the American Psychological Association has described as seeing drug users as people with an illness, offering syringe service programs, utilizing other mobile services for users who are not ready to enter treatment, etc.

Following an opioid crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, the Portuguese government in the early 2000s changed its laws to decriminalize the possession of narcotics. When that decriminalization was combined with a harm-reduction approach, the Portuguese population saw a dramatic decrease in heroin users, drug-related deaths and HIV diagnoses.

“It just was a completely different attitude there,” he said. “The goal isn’t abstinence. The goal isn’t to get people into treatment. The goal is to keep people alive, to get people healthy. That was the first time I heard somebody saying exactly what I felt.”

* * *

To be sure, harm reduction is not embraced everywhere. In the U.S. it’s a controversial topic that, depending on which state you’re in, can be met with a high level of resistance. Even in Portugal, it’s become more of a hot-button topic in recent years.

Ideally, Claborn said, abstinence-only and harm-reduction approaches should “work together” and not be “dichotomous.”

“The philosophy behind harm reduction is to meet people where they’re at,” she said. “[However], some people just genetically and the way their brain is made cannot use in a moderate way, so even just having one drink can … create significant problems.”

“I would say a lot of harm reduction is to acknowledge that there are people who need abstinence only,” said Claborn, who has been hired as an expert by the plaintiffs in much of the opioid litigation across Texas to develop an ideal system to address the opioid crisis, and in turn, other forms of addiction.

Equally important, she said, is treating mental health and substance abuse in tandem. Historically, they have been treated separately in the U.S., and despite the acknowledgment among practitioners and researchers in recent years that treatment for mental health issues and substance abuse should co-exist, the integration of services has remained siloed due to “structural challenges,” she said.

“This is where the scholarship that Jas is funding comes into play,” Claborn said. “It helps bridge that gap and it allows training in mental health for social workers but also those specializing in addiction. This is something we need to see more of. We’re starting to see more master’s programs in social work … not just the academic setting but from a policy standpoint. We need to see states actually certify programs requiring cross training in mental health and substance use, whereas now they do not. It’s pretty separate, [and a] huge problem.”

And while it’s not unheard of for there to be professionals who have both legal degrees and master’s social work degrees, Claborn added that substance use treatment would hugely benefit from a growth in the field of people who have both specialties.

“If we can have more individuals who are doing social work and law, it will have a tremendous impact on policy change and reform,” she said. “It’s something we historically haven’t seen people with a lot of cross training in. We really need a lot more advocacy within the space.”

* * *

Equally challenging is getting graduate social work students to pursue careers in substance abuse treatment to begin with — either on the clinical or policy side — said Marie Cloutier, executive director of development and constituent relations at UT’s Steve Hicks School of Social Work.

At UT, to get a master’s degree in social work (which is how you become a licensed social worker), graduate students are required to complete practicum work — what other schools may describe as internships — at a selection of various partnering agencies. But because the substance abuse treatment-focused practicum placements are often either unpaid or only pay a low stipend “that doesn’t really equate to … earning a living wage,” Cloutier said, many students who would otherwise pursue a substance abuse treatment path choose better paying practicum options, even if the subject matter isn’t what they’re truly interested in.

But Sethi’s scholarship helps bring down those barriers, she said.

She said a vast majority of UT’s graduate social work students are paying their own way through school, so if they are not getting paid for their practicum work, “it’s an incredible financial hardship,” she said.

“They cope with it through getting aid from us, taking out a loan or basically burning the candle at both ends and continuing to work another job, which leads to complete burnout and exhaustion,” Cloutier said. “Jas’ scholarship essentially [evens] the playing field of our students who are … really interested in pursuing a career working with patients in the realms of addiction, substance abuse disorder and recovery.”

Sethi said the $200,000 endowment is funded through a $100,000 pledge he has personally made, and the other $100,000 will be matched through a scholarship fund set up by school founder Steve Hicks that Cloutier said matches gifts of $50,000 or more.

So far, $60,000 of the endowment has been funded. But anyone else inclined to give to the cause or to honor Simran is welcome to donate and can do so at this link.

Cloutier anticipates that the scholarship’s inaugural award for the 2024-2025 school year will be given to one student, but thereafter, at the current level of funding, it will be available to at least two students each school year.

“There would have been a handful of fantastic candidates in this year’s class that would have loved to have gone to a [substance abuse treatment-focused] agency but couldn’t just because they had to pay for daycare for their kids or pay rent so instead went to a place they could get a $3,500 or $5,000 stipend,” Cloutier said.

* * *

Asked what Sethi has learned about his sister’s depression, he said at the time he didn’t “understand that it was literally life and death.”

“I knew that there were some issues with depression that my sister had but in my head it was just going to work [out] differently, which in retrospect is ridiculous,” he said. “I think it’s made me realize that she was scared of disappointing me … I was hard on her at times, and I had high expectations of her. Now the people in my life … there are no expectations. It goes back to I want you to be healthy, I want you to be safe, I want you to be alive.”

“Anything on top of that is just a bonus.”