Running a marathon is really, really hard.

Winning one is even harder.

Andrew Wirmani, the assistant U.S. attorney in the Northern District of Texas who headed the prosecution of the Forest Park Medical Center health insurance fraud case, said the two-month trial in the spring of 2019 was a marathon like he’d never experienced. And Wirmani, an 8-year veteran of the U.S. attorney’s office who has focused on white-collar corruption cases, has seen his share of marathons.

In an exclusive interview with The Texas Lawbook, Wirmani discussed the complexities of the Forest Park case, the sacrifices required of the government lawyers who prosecuted it and the message the prosecution sent to unscrupulous doctors and hospital executives everywhere.

“Those in the healthcare industry are aware that the federal government takes kickback schemes seriously and that we have the means to address them,” he said.

Also playing prominent roles in the successful Forest Park prosecution were assistant U.S. attorneys Marcus Busch and Katherine Pfeifle.

Wirmani is no stranger to white-collar fraud schemes. He has prosecuted, among many others, onetime Dallas Mayor Pro Tem Dwaine Caraway, who pleaded guilty in 2018 to tax evasion and conspiracy in connection with a bribery scandal involving Dallas County school buses.

Caraway, who was sentenced to 56 months in prison, admitted taking $450,000 in bribes from a company that won a contract to supply stop-arm cameras for Dallas-area school buses.

In the same case, the government squeezed a guilty plea out of former Dallas City Council member Larry Duncan, who admitted taking nearly $250,000 in bribes from the CEO of the company seeking the lucrative school-bus cameras contract. Duncan was sentenced to six months’ home confinement.

Wirmani also prosecuted a onetime Dallas police officer, Matthew Rushing, who admitted falsifying traffic citations in order to boost his overtime pay. Rushing pleaded guilty in 2019 and was sentenced to three years’ probation.

Those cases paled in their complexity and scope compared with the Forest Park Medical Center investigation.

***

Six feet tall, broad-shouldered and (at least in the courtroom) unsmiling, the 40-year-old Wirmani is the prototypical G-man. With a Sig Sauer 9 mm, or mirrored shades and an earpiece, he could easily pass for an FBI agent or a member of a Secret Service protective detail.

In court, the 2006 graduate of the University of Texas School of Law is a no-nonsense, nuts-and-bolts prosecutor. He’s soft-spoken and untheatrical – more Billie Eilish than Dua Lipa. Wirmani never raises his voice; it’s sometimes hard for spectators sitting just a few feet behind him to hear what he’s saying. He never takes the bait when defense counsel harrumph about an overreaching government engaging in underhanded tactics to trample on their clients’ constitutional rights.

His unrelenting eye-on-the-ball approach leads some defense lawyers to characterize him as inflexible, even sanctimonious. Those who work with him see instead a singularly focused public servant committed to bringing down those who would game the system for personal gain.

He’s probably not the first guy you’d choose for a comedy skit at a bar association fundraiser. But he’s definitely someone you’d want on the case if a crooked investment advisor wiped out your parents’ savings.

***

Forest Park, a physician-owned surgical hospital (now long gone) at 11990 North Central Expressway in Dallas, was the hub of an insurance scheme as brazen as it was simple. The hospital made a fast fortune by, in the words of one government witness, “buying surgeries.” It bribed doctors, chiropractors, lawyers, nurses and others across Texas to steer well-insured patients its way, then billed insurance carriers, including some of the largest in the country, at top-dollar rates.

In less than four years, from its opening in March 2009 through 2012, Forest Park bilked insurers out of more than $200 million while paying out $40 million in bribes and kickbacks, according to government records. The largest payoffs went to surgeons, whose money was laundered through shell companies and disguised under ostensible contracts for consulting or co-marketing with Forest Park.

Nine physicians and 12 other individuals were indicted by a federal grand jury in Dallas on Nov. 16, 2016. Nine of those 21 defendants, including five doctors, eventually went to trial, after many co-conspirators cut deals with the government and cooperated in the investigation.

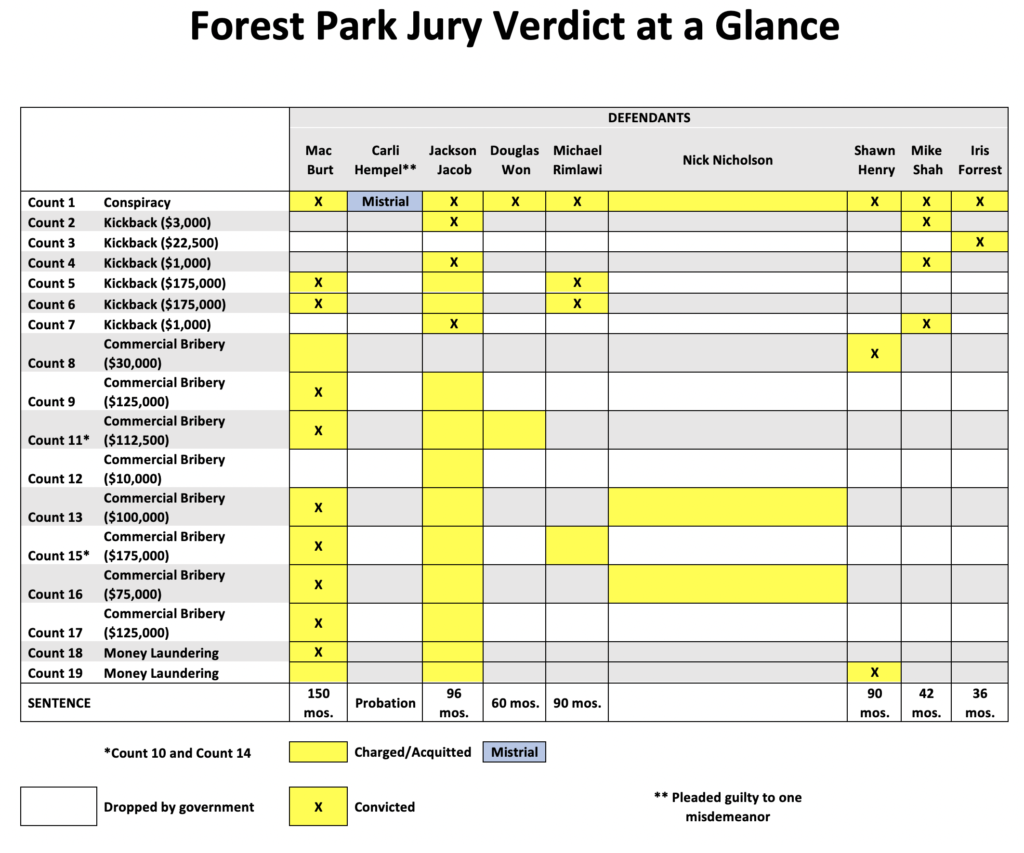

Seven of the nine who went to trial were found guilty by a jury on April 9, 2019:

– Mac Burt, who ran the hospital with a fellow executive, Alan Beauchamp (Beauchamp testified against his former business partner in a plea bargain);

– Douglas Won, Michael Rimlawi and Shawn Henry, all spinal surgeons;

– Mike Shah, a pain-management physician;

– Iris Forrest, a nurse; and

– Jackson Jacob, a businessman through whom Forest Park’s illegal payments to doctors were laundered.

The jury couldn’t reach a verdict regarding one defendant, Carli Hempel, a midlevel Forest Park manager. She later pleaded guilty to one misdemeanor count and was sentenced to three years’ probation.

One defendant was acquitted: Nick Nicholson, a prominent weight-loss surgeon who was represented by Tom Melsheimer, managing partner of the Dallas office of Winston & Strawn.

Two weeks ago, the defendants convicted at trial, together with three of the government’s cooperating witnesses, were sentenced by U.S. District Judge Jack Zouhary, a visiting judge from Ohio. In 2017, Zouhary took over the case from U.S. District Judge Sid Fitzwater of Dallas, who agreed to relocate temporarily to Amarillo to help clean up a backlog of cases on the federal docket there.

All told, the Forest Park case was a rousing success for the feds. Counting those convicted at trial and those who entered into plea-bargains, 14 defendants were sentenced to a collective 74 years in prison.

“Patient needs, not physician finances, should dictate where, when and how patients are treated. Money should never be allowed to influence medical decisions,” said Prerak Shah, acting U.S, attorney for the Northern District. The prison sentences, he said, “send a strong deterrent message: Violate anti-kickback laws, and you will face consequences.”

After the sentencings effectively brought the Forest Park trial to a close – one government witness, bariatric surgeon David Kim, remains to be sentenced because he’s still cooperating in an unrelated tax-fraud investigation – Wirmani agreed to speak with The Lawbook. Here are excerpts. (Questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.)

The Texas Lawbook: What were the origins of the Forest Park case?

ANDREW WIRMANI: It was a confluence of things. There was a separate case against Dr. Richard Toussaint [an anesthesiologist and co-founder of Forest Park] related to his anesthesia claims, billings for anesthesia when he wasn’t even present in many instances. We received a complaint from someone associated with Toussaint’s practice about not only his anesthesia claims but also, more generally, about some practices at Forest Park, including very preliminary information about a marketing fund that may have had something to do with patient referrals.

We also received a complaint from a major insurance company, mainly related to services performed by bariatric doctors at Forest Park. The insurer noticed multiple diagnoses of hiatal hernias in cases where patients didn’t have bariatric coverage. There were also concerns about the use of the emergency room at Forest Park. [As a surgery boutique close to much larger hospitals with full-service ERs, Forest Park should have had few if any billings for trauma care.]

And third, there were persistent rumors about Forest Park in the medical community. We began to hear from investors, primary care doctors who weren’t surgeons, who said they were getting threats: In exchange for their investment, they needed to meet certain quotas for patient referrals.

All of that came together and put Forest Park squarely on the government’s radar.

Lawbook: At the time, doctors we knew were scratching their heads, wondering how Forest Park was raking in so much money.

Wirmani: The economics didn’t make sense. Even some defendants who cooperated with us were surprised that the hospital was profitable as soon as it opened. That almost never happens.

Lawbook: Much has been written about the use of the Travel Act in this case to essentially “federalize” state offenses and go after defendants even if they had no federally insured patients. This wasn’t the first use the act in a white-collar fraud case, but it was unconventional. Where did the idea come from?

Wirmani: We knew from the beginning that Forest Park was almost exclusively a private-insurance, out-of-network hospital. We did discover later that in fact they had a good deal of federal billing, but the vast majority of their activity was with privately insured patients. There are various theories federal prosecutors have looked at over the years, honest services wire fraud being one. Since there were some federal dollars, there was the potential to charge bribery under 18 USC 666.

In the Biodiagnostic case in New Jersey, which was still in its infancy, they were using the Travel Act but in a different manner. Instead of one large indictment, they were picking off doctors and marketers one by one, and with a reasonable degree of success.

I spent a good deal of time digging into the arguments we could anticipate and satisfied myself that it was a viable theory. We ultimately came to the conclusion that the novelty aspect of it wasn’t really that important. We had to prove to the jury, which we did, that these defendants knew what they were doing was unlawful. That assured us that arguments about fairness and equity [in charging under the Travel Act] probably wouldn’t have legs.

Lawbook: Yet, while you had great success in the verdicts from top to bottom, most of the Travel Act counts didn’t result in convictions.

Wirmani: Mac Burt was convicted on several Travel Act counts. Shawn Henry was convicted on one. And the jury found two money-laundering conspiracies that were predicated on Travel Act proceeds. So, I do think the government’s theory was accepted by the jury in large part. There were individual counts with respect to certain defendants in which the jury acquitted. That’s just the nature of a jury trial.

What’s really important for the healthcare industry going forward is that the government – with some very, very capable defense lawyers on the other side – successfully dealt with a number of legal challenges to the viability of the prosecution theory. Going back to when Judge Fitzwater was on the case, he issued a lengthy order knocking down the defense arguments and affirming that this was a viable theory. So, regardless of how the facts might play out in a particular case, that precedent is there.

Lawbook: Since the convictions, have you spoken at conferences or made presentations to prosecutors around the country on using the Travel Act in medical-fraud cases?

Wirmani: Yes. I’ve talked to prosecutors in California and Florida who were interested in the case and were dealing with similar issues. There have been a handful of cases since Forest Park where the Travel Act has been successfully used, with similarly supportive judicial opinions.

I’ve also spent a lot of time speaking to healthcare conferences to make sure those in the healthcare industry are aware that the federal government takes these types of kickback schemes seriously and that we have the means to address them.

Lawbook: There was testimony at trial that some doctors received legal advice that their arrangements with Forest Park were legal. Separately, we’ve been told it was once fairly common for lawyers to advise doctors that their chances of being prosecuted under the Texas commercial bribery statute were remote, since the state rarely if ever used that statute against physicians. What did the guilty verdicts say about that advice?

Wirmani: Speaking generally, not just about Forest Park, there certainly are legal, viable ways to have co-marketing agreements in the healthcare industry. The government never disputed that. Whether the contracts with Forest Park were the types of arrangements that wouldn’t cause concern is difficult to speak to, since some of those contracts weren’t super, super clear.

But from the government’s viewpoint, what was important was that both the contracts and the doctors’ lawyers told their clients, “You can’t take money for patient referrals.” This is where the concealment aspect came in: The defendant doctors were receiving advice that their marketing and consulting arrangements with Forest Park, on their face, appeared valid. But then they used that as a shield for what their actual intent was.

To the question of what lawyers were telling their clients about state law, I’ve never spoken to a lawyer who ever told a client it’s OK to take kickbacks, as long as there’s no federal insurance money involved. I think typically the legal advice people were receiving – and I know this from talking to several transactional healthcare lawyers – is that yes, there is a state anti-kickback statute or a state commercial bribery statute, but enforcement in that area is not nearly as vigorous as it is on the federal-dollars side. They weren’t telling their clients, this is legal. They were telling them, this is illegal, but there’s less scrutiny.

It comes down to what Alan Beauchamp said at his sentencing: We did the risk analysis, and we thought there was a low risk of getting caught.

Lawbook: Defense lawyers spoke indignantly about the government’s tactics in arresting their clients: Armed FBI agents banging on the door at 6 a.m., red lights flashing, doctors being dragged out half-undressed in front of their neighbors and kids … it’s not like you were arresting Machine Gun Kelly. A physician probably wasn’t going to come out with both guns blazing. Was this done to send a message to these defendants?

Wirmani:I can’t speak to the character of the arrests. I wasn’t there. I can say that neither my office nor any federal agency would use an arrest to send a message to a defendant, whether it’s a drug dealer or a white-collar criminal. The objective is always to bring somebody into custody in the safest, most efficient way possible. Our focus is on officer safety.

It just takes one defendant who reacts badly for an agent to get killed. It just happened down in Florida, with agents serving a search warrant. It’s a dangerous job, even when they’re arresting a white-collar criminal.

Lawbook: How do you prepare for a 2-month-long trial? How did you get through it from day to day? Even for a spectator, listening to a full day’s testimony is draining. Then your team had to go back to the office and prepare for the next day.

Wirmani: It was a marathon – certainly the longest case I’ve tried, and I’ve tried some long ones. The fact that Judge Zouhary took most Fridays off was helpful. You kind of break a trial up into segments. We used those long weekends to prepare for the next segment.

Most of the folks on the trial team have young kids, so we did try to take off one day a week to spend with our families. But other than that, even going back a couple of months before the trial started, it was basically nonstop. There were pretrial pleadings to file, a bunch of legal challenges from the defense to wade through, witnesses to interview. Typically, I like to prep witnesses a couple weeks before they testify. But when you’re putting 50 witnesses on the stand, there’s no way you can jam that prep into a few weeks before trial. We ended up doing a lot of our prep during the trial.

Lawbook: Nine defendants were being tried together, but you had to present nine individual cases to the jury: Here’s what Dr. X did, here’s what Dr. Y did. Did you worry that over the course of two months jurors would lose track of which defendant did what when?

Wirmani: It was logistically challenging, just given the number of people in the courtroom and the number of cross-examinations all of our witnesses had to endure. We spent countless hours trying to simplify as much as possible, to make sure we were keeping to our key themes with every witness, every document. Even during the trial, there were things we cut back on to try to simplify the case for the jury

In the end, I was pleasantly surprised at how well the jury understood our case. There’s always a fear that with talented lawyers on the other side, confusion is going to reign, which can lead to acquittals or a hung jury.

A long, involved trial is grueling on jurors. I always try to remember they’re taking time out of their workday and their family lives to sit there and listen to our presentation. We tried to be respectful of their time and get our point across in as succinct a manner as possible.

Lawbook: A lot of healthcare fraud prosecutions have been coming out of the Northern District lately. Is there more fraud going on than there used to be? Or is this something the federal government has gotten more interested in? In other words, do we have an inordinate number of bad actors or an exceptional number of good prosecutors?

Wirmani: Healthcare has always been a priority of the Justice Department. DFW just has a lot of bad actors. Ninety-nine percent of doctors and others in the healthcare industry do their jobs well. They care about patients and patient finances. But there are those bad apples out there, and they do seem to be particularly concentrated in Texas. I’m not really sure why.

Of late, we’ve had additional strike force resources in Texas, and that’s led to increased prosecutions. We have a lot of talented healthcare prosecutors in this office, and it’s definitely been an emphasis, maybe more so than in some other districts.

You also have a densely populated medical community here. It’s difficult to drive down the street without seeing a surgical center or an emergency clinic or a hospital. There are lots of providers, and some of them try to take advantage of the system.

Lawbook: Last question: The surgeons in the Forest Park case would have made millions of dollars if they’d never broken the law. They were better off financially than 99.99% of the people in America. They lived in mansions, drove luxury cars, could buy whatever they wanted. Do you ever wonder why someone making, say, $10 million would risk everything to make $12 million?

Wirmani: With most crimes, you can dig down and come up with some root cause. It doesn’t make the crime excusable, but usually you can point to something and say this is why it occurred. Maybe the person was addicted to drugs, or they were down on their luck and got pushed to the brink and made a bad choice.

But when you’re dealing with white-collar fraud, it’s uniquely hard to understand. At the end of the day, it comes down to greed and arrogance. Some people never have enough, and that pushes them to do things they later regret.

For me, sentencing is always a sobering time. It’s never something to celebrate. These are real people with real lives, and it’s sad to see where their choices lead them. It takes a toll on prosecutors to see those families [of defendants] in the courtroom, to see the lives destroyed. That’s not easy to watch.

But those choices, ultimately, come down to the defendants. They’re the ones who bear the responsibility for the damage they caused.