Michael Massengale was an ocean away from Texas, enjoying a break from his arbitration practice and sampling European cuisine and culture with his wife Lindsey, last May 24 when he heard the stomach-churning news of a mass shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde.

“I remember it vividly because we were at dinner and got the notifications on our phone that this horrible thing was under way,” he said. “It was still unfolding at the time, and we were in a relatively small place. And we realized that a table across from us, about 20 minutes later, they had all gotten the same news and were talking about it. And they were all from Texas.”

What Massengale, a former justice on the First Court of Appeals, couldn’t have known at the time was that he would soon be immersed in the tragedy, which had claimed the lives of 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers and left 17 others injured. He didn’t imagine that in a matter of weeks he would be standing outside Robb Elementary School studying the enlarged photo memorials of the slain innocents while vowing to honor them by telling the truth about what had happened inside the aging school building on that horrible day.

Over an intense six weeks Massengale would complete an assignment as challenging and complex as any of the 600 signed opinions he has written. As the primary drafter of a report detailing the findings of an investigation commissioned by the Texas House of Representatives, Massengale would rely on skills he acquired as a litigator, jurist and arbitrator.

The three members of the Investigative Committee on the Robb Elementary Shooting say Massengale’s background, dedication to detail and writing skills were pivotal to the investigation.

“Mike’s past judicial and courtroom experience was a valuable asset in determining the facts of what happened on that day in May 2022,” said Rep. Dustin Burrows, a Lubbock Republican and litigation attorney at Liggett Law Group who led the committee. “There was a tremendous amount of interest by the public and the Texas legislature in bringing clarity and accuracy to the tragedy and how it unfolded.”

The resulting report would dispel rumors and shine a harsh light on one of the most embarrassing law enforcement chapters in Texas history. The report’s findings about operational breakdowns and lax school security are guiding legislation aimed at improving training and communication for first responders and increasing school safety requirements and compliance.

Massengale, 50, recently spoke with The Texas Lawbook about writing the report and why there is plenty of blame to go around for the dismal response to the worst school shooting in state history.

Complicated, Sensitive Inquiry

Still absorbing news of the tragedy from abroad, Massengale learned that House Speaker Dade Phelan had named a three-member committee to “make a complete and thorough examination of the facts and circumstances surrounding the shootings and murders.” The attack came just four short years after a high school shooting killed eight students and two teachers at Santa Fe High School in Galveston County.

Burrows would chair the committee. The other members were Rep. Joe Moody, an El Paso Democrat, and Eva Guzman, a former Texas Supreme Court justice and Massengale’s close friend.

Guzman says she suggested to Burrows that Massengale would be a good choice to write the report. Committee members were gearing up for a complicated and sensitive inquiry and knew the report would be closely scrutinized by a skeptical public. The initial praise for law enforcement actions by Gov. Greg Abbott and others had proven to be unwarranted and was quickly walked back once it became clear that responders had waited more than an hour outside the classroom where the shooter lurked — even while gunshots were fired and students were calling 911 pleading for help.

“I know that he is always very serious about any task that he undertakes, and I knew that he would be able to help the committee deliver to the people of Texas a report that was thorough, that was fair and that provided the people of Uvalde much-needed answers, much-deserved answers,” Guzman said.

On June 4 Massengale was self-isolating in a Paris hotel room, his return to America delayed after testing positive for covid, when Burrows called to talk about the investigation.

“Part of what we discussed was that their timeline was they wanted to turn out a report in six weeks, which would have put us into the middle of July, and we were starting from ground zero,” Massengale said. “I think we both had a recognition that it was a very tall task to get it done.”

The Texas Legislative Council agreed in a contract to pay JAMS for work performed by Massengale at the hourly rate of $450 with total compensation capped at $75,000.

The report would dispute conclusions made in an earlier, rushed report from a law enforcement training center that an Uvalde cop could have shot the attacker outside the school and that early officers on the scene had rifle-rated body armor.

It would expose a culture of noncompliance at the school to secure exterior and classroom doors. And it would make clear to readers the mistakes of law enforcement responders who failed to follow their training, spent precious time looking for keys to a door that likely was unlocked and neglected to establish a command center for the hundreds of local, state and federal officers who converged on the school but failed to confront the shooter for an agonizing 73 minutes as frantic parents waited outside.

“At Robb Elementary, law enforcement responders failed to adhere to their active shooter training, and they failed to prioritize saving the lives of innocent victims over their own safety,” the report states.

A Writer at Heart

Massengale’s work on the school shooting report would draw on his experience as a trial lawyer, court of appeals judge and arbitrator with JAMS. He has participated in the resolution of thousands of appeals and has written more than 600 signed opinions, exercises in collaboration that would prove valuable in crafting the bipartisan report.

“As a trial lawyer you learn how to gather and collect information for a case, and then as an appellate judge you have to write opinions where you lay out the facts,” he said. “And in my work today as an arbitrator, same thing: You have to pull together all the available evidence and then write it up.

“And we’re judged, as you know, based on the quality of our ability to do that. And one of the reasons I liked to be an appellate judge and why I like being an arbitrator now is I really like writing.”

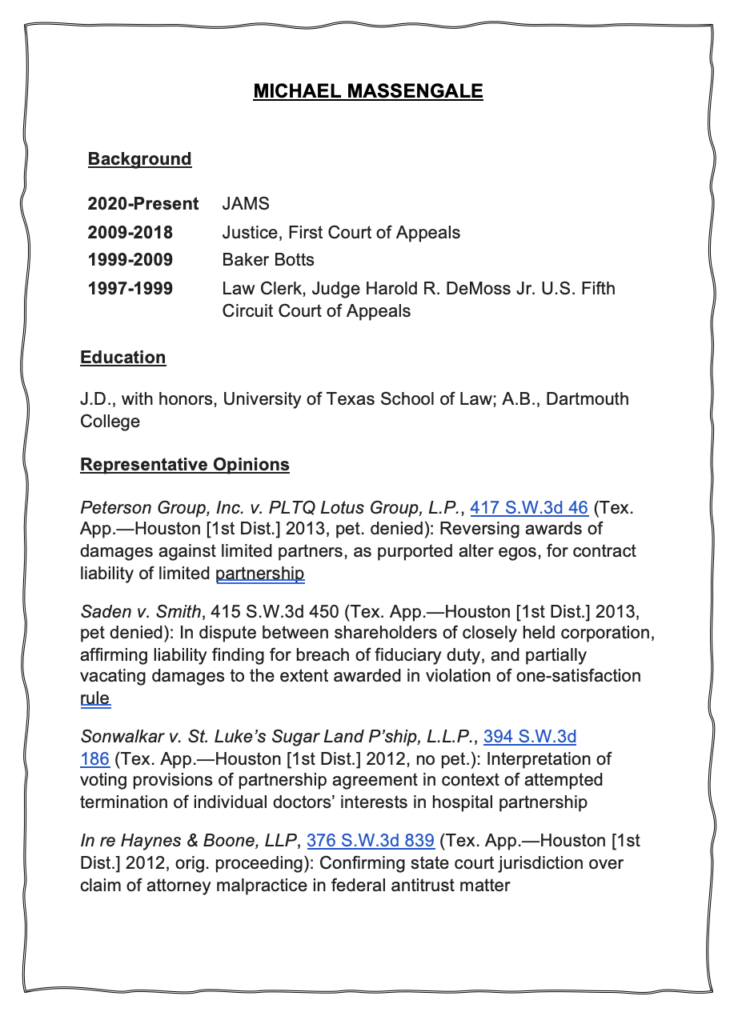

Massengale’s father was in the Air Force, and he lived in many different places growing up. After receiving his J.D. with honors from the University of Texas School of Law in 1997, he was a law clerk to Judge Harold R. DeMoss Jr. at the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. He worked as a litigator at Baker Botts for 10 years prior to being appointed by Gov. Rick Perry in 2009 to the First Court of Appeals.

Massengale credits Guzman with helping him as he began work at the court of appeals, where he was surprised at the volume of child welfare cases. Guzman, who at the time served on the Fourteenth Court of Appeals, also based in Houston, had handled those cases as a family court judge in Harris County.

“They are cases that are treated by the courts as very important cases because you’re disrupting a family and you have a child involved, and they have to be handled more quickly than we’re accustomed to. I mean, a year or two in the life of a child is an eternity, right?” Massengale said. “She and I had a lot of in-depth conversations as I was learning about that and being a judge in general and having to run for office. And we would drive together to events and we struck up a friendship.”

When she was appointed by Perry to the Supreme Court in 2009, Justice Guzman was assigned the responsibility of overseeing the court’s Children’s Commission, whose mission is to strengthen courts for children and families in the child welfare system. She tapped Massengale to serve on that commission and for his current position on the Texas Access to Justice Commission, which works to improve justice in civil legal matters for low-income Texans.

Massengale ran for a seat on the Texas Supreme Court in 2016 and was defeated in the Republican primary by incumbent Justice Debra Lehrmann. He sought reelection to the First Court of Appeals in 2018 but lost in the general election as Democratic candidates scored historic victories on several urban intermediate appellate courts.

In 2020 Massengale joined JAMS, the largest provider of alternative dispute resolution services worldwide. Chris Poole, JAMS president and CEO, said in the announcement that Massengale “is known for his strong work ethic, well-reasoned opinions and careful approach to every case that comes before him.”

Guzman, who served on the Supreme Court from 2009 until 2021 when she resigned to run for attorney general, turned to Massengale for advice on her campaign against AG Ken Paxton and challenger George P. Bush. After failing to make the primary runoff last year, she joined Wright Close & Barger.

First-Draft Challenge

Meeting at the Capitol on June 9, the committee immediately went into executive session and heard from Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steve McCraw about the attacker’s background, the incident timeline and the response by law enforcement.

The committee traveled to Uvalde in mid-June for three days of closed-door testimony from school district employees and law enforcement, as well as members of the attacker’s family. Committee members toured Robb Elementary and laid a wreath at the school memorial. Families of the victims were notified about the investigation, and some met with committee members.

It was while he was waiting outside the school that Massengale studied the enlarged photos of the fourth graders and their teachers and read about their personalities and interests. The committee decided the report would be dedicated to those whose lives were lost and includes simple, yet poignant remembrances of each one.

“But it wasn’t until that moment where I stood in front of them individually and saw how they dressed and what their interests were — and in retrospect, it’s stunning to me that I hadn’t drawn this connection — but I have a niece who is that same age who lives with us in our house,” he said.

“It really hit home with me that these are kids just like my niece and all her friends that I see all the time, and just sort of the humanity of those victims was really impressed on me in that moment.”

The committee held other hearings in Uvalde and Austin, ultimately interviewing 35 witnesses. The committee defended its private sessions, saying the method served the goal of an objective fact-finding process by allowing members to engage in candid discussions with witnesses.

Massengale was in the room when the committee members, all lawyers, questioned witnesses under oath, a process that drove the findings of the report. Like his experiences as a member of a three-justice panel hearing arguments on an appeal, he listened carefully to their questions for insight on how individual committee members were viewing the evidence.

Guzman, whose husband was a Houston police officer was “very knowledgeable and interested in the law enforcement angle.”

Rep. Moody represents a community that experienced a 2019 mass shooting that claimed 23 lives at an El Paso Walmart perpetrated by a young man who drove from North Texas to target Hispanic immigrants. Patrick Crusius recently pleaded guilty in federal court to various hate crimes and weapons charges.

“That was a very raw experience that he and that community are still working through,” Massengale said. “And he displayed an amazing empathy to everybody in the community. And I thought that was very helpful for the committee and something that I think is reflected in the report, the empathy for the community.”

Moody says that Massengale was an “incredible addition to the Robb investigation.”

“As a longtime criminal law attorney, I found it enlightening to see the unique perspective he brought to the work from a civil and appellate background. Above all, his attention to detail and commitment to precision in both our investigation and report were crucial in shaping the answers we delivered for Texans in the wake of this tragedy,” Moody said. “He was also just a nice guy who was easy to work with — that’s not something we highlight enough in legal circles, but we should, because it makes all the difference in getting the results the people we serve deserve.”

Massengale is one of 11 individuals acknowledged as helping with the investigation and preparation of the report. Casey Garrett, a criminal law specialist, was lead investigator and oversaw informal interviews with 39 people in addition to the 35 sworn witnesses. Investigators and House staff attorneys reviewed crime-scene photos, surveillance camera footage, mobile phone video, 911 calls, radio transmissions and body camera footage. They combed through thousands of pages of documents, including school safety plans, school disciplinary records, ballistics reports,

“We were dividing and conquering our review of all this information that we had received and were gathering,” he said. “And none of [the committee members] had the ability to individually read all of this stuff for themselves, watch all of the body cam videos themselves, listen to all the radio traffic themselves, review the thousands and thousands of pages that we had themselves.”

It was Massengale’s job to harness the trove of material and bring the various elements together in a logical narrative that would be acceptable to the bipartisan committee. He compared it to his work as an appellate jurist considering enormous trial records, legal briefs and opinions from his colleagues on the court in crafting a majority decision.

“We kind of came to a point along the way where I just had to hunker down and crank out a first draft, and that was a challenge,” he said. “It was an organizational challenge to decide how you’re going to break it up and start from a blank page to, you know, getting something that people can look at and then react to and comment on.”

He used extensive footnotes to document the sources for the report’s conclusions. It was another lesson from his appellate work. Massengale says he always felt uncomfortable reviewing a draft opinion circulated by another judge’s chambers that did not provide “footnotes or other kinds of references that would allow me to go and look behind the work of the staff attorney who had prepared the draft.”

At the same time, Massengale knew the committee report would not bear his name as an author.

“I am fully confident that, you know, it is their product,” Massengale said. “But it was a huge honor for me to have the responsibility to help them by getting it all on paper. And then, of course, once I did have something that I could circulate, then it was their turn to all go dark because they all had to look at it.”

The feedback was robust as Massengale continued to make revisions. Guzman says the committee “had one mission, one purpose, egos were left at the door, and everyone collaborated in the most collegial and professional manner.”

Setting the Record Straight

In early July as the committee was working on its investigation, a separate report was issued by the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center at Texas State University. The ALERRT report — largely based on a one-hour DPS briefing — made headlines by stating that an Uvalde police officer asked for a supervisor’s permission to shoot the gunman before he entered the building, but the supervisor did not hear the request or responded too late.

Uvalde’s mayor disputed that account in a written statement. The House committee also concluded that it is more likely that the person dressed in black said to have been observed carrying a rifle was the coach who was telling children on the playground to run away from the school.

“So ALERRT had not done any independent investigation,” Massengale said. “I’m speaking for myself now and not anybody else. I think, unfortunately, they got used and their credibility got used by people who wanted to get sort of a certain narrative out. And I think the committee felt very strongly once that was out there that they had to set the record straight on some particulars.”

A section of the House report, published July 17, asks “What Didn’t Happen in Those 73 Minutes?” referring to the time between when officers swarmed the school, retreated to hallways when shots were fired at them, and a U.S. Border Patrol tactical team finally entered the classroom and killed the attacker. During that time, 376 law enforcement officials amassed at the scene, with many stationed outside where frantic parents were trying to rush into the school to save their children.

“A major error in the law enforcement response at Robb Elementary School was the failure of any officers to assume and exercise effective incident command,” the report states. “Responders did not remain focused on the task of ‘stopping the killing’ as instructed by active shooter training. They never attempted to breach the classroom before [the Border Patrol Tactical Unit] accomplished entry.”

The report reaches disturbing conclusions about the school’s “culture of noncompliance with safety policies requiring doors to be kept locked, which turned out to be fatal.” Poor Wi-Fi connectivity and failure to use the school intercom delayed the lockdown. Precious time was spent looking for keys while no one checked to see if classroom doors were locked, and the committee concluded that the door to one of two connected classrooms where the killings took place was faulty and probably was not effectively locked shut.

Frequent border-related alerts involving human traffickers trying to outrun the police contributed to a diminished sense of vigilance about responding to security alerts, the committee reported.

Family members of Salvador Ramos, a troubled high school dropout, knew he had bought two AR-15-style rifles and a large amount of ammunition soon after he turned 18. His social media chats about school shootings and violence never were reported to law enforcement. The report does not name or picture the attacker to deny him the notoriety he may have been seeking.

Massengale says that the first officers did not enter the school until after the attacker had been inside for two-and-a-half minutes and had likely fired more than 100 rounds.

“The reality is that most of the carnage had already occurred and would not be undone by anything that they had done correctly at that point,” Massengale said. “But what if the exterior door had been locked? What if the interior door had been locked? What if they had had a higher fence? If you slowed him down two or three minutes?”

Pete Arredondo, the Uvalde school district police chief, has shouldered most of the blame for the chaotic scene at the school. He was fired from his job and removed as a newly-elected Uvalde city council member.

DPS has attempted to deflect responsibility by stating that jurisdiction over the response belonged to Arredondo and that state troopers had no legal authority to walk into the scene and take over. While that may be technically correct, it is an incomplete assessment, Massengale says.

“Just because you don’t have legal authority to override him and replace him does not mean that when you get there and observe a deficiency that you cannot approach him or one of his subordinates and say, ‘How can we help you to set up a command post? We notice that you are here inside the building so you can’t be the person in command outside of the building. So can we either leave you here or establish the command post outside?’

“They should be trained about how they work together on the scene,” Massengale adds. “It can’t be the case that you have all of these highly qualified, trained, equipped people there who are just supposed to stand around because poor Pete Arredondo was in over his head that day.”

The report is written in a clear narrative. It states upfront that more information is likely to come out and that some aspects of its interim findings may be disputed or disproven in the future.

The document includes photos showing armed police in school hallways and screen shots from the attacker’s chilling online chats about his purchase of weapons and ammo. The final seven pages are devoted to the committee’s factual conclusions.

The report generally was well-received, although the committee faced criticism for not releasing a Spanish translation. Massengale says the committee wanted to meet its deadline and planned to follow up with a professionally prepared Spanish version. The Austin American-Statesman had the report translated into Spanish and drove 10,000 copies to Uvalde four days later. The committee’s Spanish version soon followed and is available on the House website.

Massengale says the committee was sensitive to the needs of the Uvalde community and fielded questions at its news conferences from Spanish-speaking media. “I thought that was a very unfair criticism because having observed it firsthand, I think the committee was very, very concerned about following a process that was designed to respond to the community’s needs,” he said.

With legal claims mounting against the Uvalde school district and city, law enforcement agencies and others, Massengale does not think the report would be a source of primary evidence in court but would “certainly be helpful for people to find the truth.” The release of a report by the Texas Rangers is pending while DPS continues to claim an exemption for public records related to an ongoing investigation.

Making Schools Safer

While the House committee was not charged with making policy recommendations, Massengale thinks the report is a useful tool for policymakers.

“I’ve had people call me and ask questions about their school, are we doing enough at our school? And from that standpoint, I think any concerned citizen or involved parent who wants to make sure that their child is in a safe environment at school would benefit from reading and learning from this.

“Because like we were discussing earlier, I think it’s extremely common for people who work around locked doors to prop doors open, take shortcuts. And if people took to heart that those kinds of rules are really important because we’re protecting the next generation, that it’s not there to inconvenience parents. It’s there because children are so precious and are deserving of protection.”

The report discusses the attacker’s purchase of guns when he turned 18, just one week before the shooting, and pictures the rifle used at Robb. In its factual conclusions, the report states there was no legal impediment to the attacker buying two AR-15-style rifles, 60 magazines and over 2,000 rounds of ammunition and that federal firearms authorities were not required to notify the local sheriff of the multiple purchases.

Gun safety bills filed for consideration during the 2023 session include proposals to raise the minimum age to purchase military-style semiautomatic rifles. Speaker Phelan has said firearm safety is “a necessary component” to the conversation about school safety. He named 13 representatives, including Burrows and Moody, to a new House Select Committee on Community Safety to hear gun safety bills.

Burrows and Moody are joint authors of HB 3, which would require at least one armed security officer at each campus. It would require school districts to conduct regular safety and security audits of facilities and give the Texas Education Agency new monitoring authority. Districts would receive additional funding to improve school safety.

The first bill passed by the Senate this session would align state law with the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, passed by Congress after Uvalde. It would require court clerks to report mental health adjudications of juveniles aged 16 years or older to DPS for reporting to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. The Senate has a priority school safety bill that would empower the education commissioner to compel school districts to establish safety protocols for active-shooter situations. House and Senate budget proposals include about $600 million for school safety improvement.

Massengale thinks the report makes a “very compelling case for looking very carefully at the state of our public school facilities and making sure that all of our public schools have the funding that they need to provide a sufficient measure of security.” He said the newest school buildings in Uvalde, a poor community, were almost 40 years old.

“When schools were being designed 40 years ago, we didn’t have the same threat of mass shootings, trend of mass shootings,” he said. “We didn’t have the benefit of all we’ve learned about what we can do to protect against those.

“You don’t want schools to be fortresses, but there has to be somewhere in between where we’re making sure that — I mean, I can’t imagine that anybody would object to making sure that locks that need to be replaced, that there’s always money for something like that.”

Massengale did not want to express an opinion about new gun laws but does support improved law enforcement training.

“I think a major deficiency of training that was shown by this report was the interaction of multiple law enforcement agencies all responding to a mass tragedy. The Uvalde tragedy showed that the responders were probably not adequately trained and certainly did not properly execute best practices for agencies working together in response to a tragedy like this,” he said.

Those who knew about Massengale’s involvement with the investigation often ask how it personally impacted him, whether he experienced a sort of secondary trauma from the work. Again, Massengale says, his experience reviewing episodes of crime and abuse during his decade on the appellate court trained him to compartmentalize the grim facts that come with the job.

“I understand the question, but it was interesting to me to hear it because that’s not your typical reaction when people find out you’re a judge,” he said. “And I guess that’s kind of true of many judges, that you have to work with sad circumstances, unfortunate things that have happened to people.

“And I know of judges who have burned out because of that. But I guess, you know, be grateful to the judges and to everybody who works with victims, because it’s hard on them as well.”