© 2012 The Texas Lawbook.

By Mark Curriden, JD

Senior Writer for The Texas Lawbook

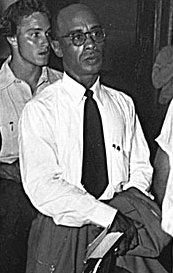

Sixty-six years ago, Heman Marion Sweatt walked into Room One of the University of Texas Tower with a copy of his college transcripts in hand and an application to be admitted into the UT Law School.

Three weeks later, UT informed Sweatt his application had been refused. The reason for the rejection was simple:

“The fact that he is a negro.”

Sweatt sued the university. In 1950, a unanimous Supreme Court of the United States ruled for the first time that an African-American must be admitted to an all-white school. The case helped shape another case that the justices considered four years later called Brown v. Board of Education.

Sweatt died in 1982, but on Monday, his daughter and other family members filed amicus curiae briefs with the Supreme Court in Abigail Fisher v. University of Texas, which challenges the law school’s consideration of race in its admissions policy.

“The purpose of the Sweatt family’s brief is simple,” says Allan Van Fleet, a litigation partner in the Houston office of McDermott Will & Emery, who is representing the family pro bono. “They want the Supreme Court to remember their father and his story.”

Van Fleet says the Sweatt family, led by Sweatt’s daughter, Dr. Hemella Sweatt-Duplechan, a dermatological pathologist, strongly support UT’s current admissions policy, which seeks to create a diverse student body by considering race as part of a holistic review of those applicants who are not admitted automatically under the Texas Top Ten Percent Law.

In 2008, Fisher challenged UT’s admissions policy as unconstitutional, arguing that the Court should overrule its 2003 opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger, which held that race can play a limited role in college admissions decisions. Fisher argues alternatively that Grutter does not apply to UT, because many minority students are admitted under the Texas law that automatically admits the top ten percent of graduates in their Texas high school class.

The Fisher case will be argued in October.

“In filing this brief, we have done our best to honor the legacy of Heman Sweatt by supporting UT’s commitment to creating and cultivating a diverse student body and by considering race only in the context of applicant’s whole character and life experiences,” says Van Fleet. “This is the kind of holistic review that UT and the State of Texas denied to Heman Sweatt.”

Sweatt, the grandson of a slave, was a black teenager who grew up in a predominantly white Houston neighborhood. He faced the indignities of Jim Crow laws and had to pass all-white schools in order to attend his all-black school.

The lawsuit against UT wasn’t Sweatt’s first anti-discrimination effort. “He walked door-to-door asking for donations to finance his lawsuits challenging Texas’ white-only primaries,” according to the brief filed Monday.

In his case against UT, Dallas lawyer William Durham and New York lawyer Thurgood Marshall represented Sweatt. The Court’s decision was the first recognition of the importance of diversity in higher education, according to Van Fleet.

The justices ruled that the separate law school was unequal, in part, because it isolated him from students “numbering 85 percent of the population of the State” and deprived him of the benefits of a diverse student body, including the interplay of ideas and the exchange of ideas with different students, says Van Fleet.

That fall, Sweatt was one of six African Americans enrolled in UT Law School. The pressure on Sweatt started to mount, causing his already frail health to worsen. He dropped out of UT during his second year.

“In UT’s holistic review …race is not determinative,” according to the brief. “No one is admitted because of his race; no one is excluded because of his race. No one is assigned to a particular program based solely upon race. Rather, the individual’s ‘whole range of talents and school needs’ are weighed in seeking the benefits of truly diverse classrooms.”

Van Fleet and McDermott associate Nick Grimmer contend that there is strong evidence that Texas primary and secondary schools are resegregating.

“After years of steady integration, frequently under the firm hand of heroic federal judges, the fact is that Texas schools are de facto resegregating,” said Van Fleet. “Each year, more black and Hispanic students attend highly segregated schools, where less than 10 percent of the enrollment comprises other races.”

“This makes it all the more important that UT be able to include race as part of a holistic review of applicants to supplement the top-ten-percent admissions, in order to create a student body with truly diverse ideas, points of view, and life experiences,” he says.

© 2012 The Texas Lawbook. Content of The Texas Lawbook is controlled and protected by specific licensing agreements with our subscribers and under federal copyright laws. Any distribution of this content without the consent of The Texas Lawbook is prohibited.